neoTropico: a complete x-ray of Latin American human trafficking

Gerardo Suter creates micro-stories from archive images, photographs recovered from social networks, and historical documents. He aims to create an immense polyhedral portrait of migration movements on the continent. In this interview, the Argentine artist reflects on the violent reality of human trafficking and the hypocrisy of governments that both punish and economically benefit from this phenomenon. Suter also talks about the evolution of his thinking around images and the internet’s impact on his creative process.

By Alonso Almenara

Five hundred thirteen undocumented migrants crowded into two containers on the southern border of Mexico: this surreal image, captured in 2011 by a Mexican immigration service X-ray camera and that went around the world, was the trigger for a large-scale project that Argentine artist Gerardo Suter has been developing over the past decade. Its name is neoTropic, a term Suter borrows from biogeography and is used to identify the tropical region of the American continent.

The word conveys a sense of virgin nature, perhaps dangerous: it brings to mind the absence of law in an environment where predatory behavior prevails. We are not far from what happens in the immense migratory corridor of Latin America that flows into the border between Mexico and the United States. Violence and abuse, whether by human trafficking mafias or border patrolling authorities, is an everyday reality affecting millions.

The United States has the most international migrants: there are 51 million, according to the International Organization for Migration’s 2022 report. Twenty-five million come from Latin America and the Caribbean. According to data from the WOLA organization, the majority are of Mexican, Guatemalan, Salvadoran, or Honduran origin. Mexico is a particular case: it is the second country in the world with the most emigrants (11 million), surpassed only by India (almost 18 million).

neoTropic is Suter’s response – necessarily unfinished and insufficient, a permanent work-in-progress – to this situation that claims lives, separate families, or forces people to live in fear. It is also a lucrative business: according to the migrants who appeared in the 2011 X-ray, the vast majority of whom were Guatemalan, the journey had cost them $7,000 each.

Gerardo Suter (Buenos Aires, 1957) holds a Ph.D. from the Universidad Politécnica de Valencia in Art: Production and Research (audiovisual languages and social culture). He began his creative work in 1976 in the field of photography. Since 1990 his interest has focused on developing proposals for specific sites where the still and cinematic image is linked to other media, such as sound or text, and architecture becomes the final support of the work. In 2010 he coined the term expanded image, a concept he uses as a starting point for his current transmedia installation projects.

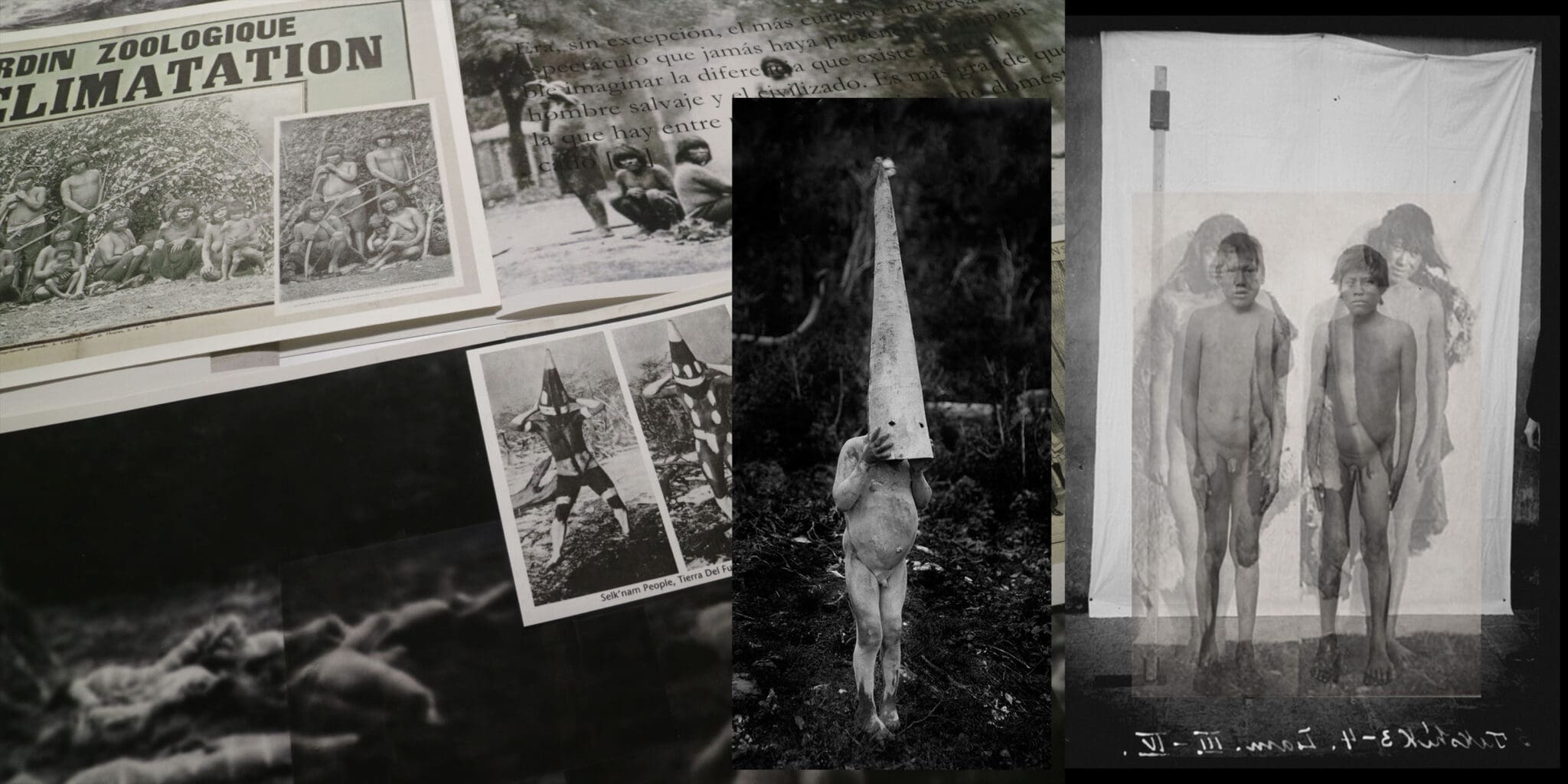

He is currently developing neoTrópico, a project that officially began in 2017 but is thematically linked to previous works around the theme of forced displacement in Latin America. At the center of these investigations is the representation of the other: the foreigner, the undocumented, the displaced, the migrant, and the clandestine. The grand ambition of neoTrópico lies in the fact that it draws on 500 years of material: it combines recent news about immigrants with texts by Fray Bartolomé de las Casas and Joseph Conrad; there are also references to Theodor de Bry’s illustrated version of the Brevísima Relación de la Destrucción de las Indias, as well as to Edward James’ records of his kingdom in Xilitla, stills from the film Apocalypse Now and videos from the night cameras that sweep the borders.

For Suter, the living conditions of undocumented migrants reflect the central conflicts of the contemporary world: their displacements for survival are a consequence of the pressing situations experienced in their countries of origin and the obscene asymmetries of power and money between social classes and territories. Walking through tunnels, hidden in various means of transportation, they are little visible, but countless victims of a globalized world where everything seems to be at the click of a button, but borders are more guarded than ever.

neoTrópico is also a test of the possibilities of the digital image by one of the notorious figures of photographic experimentation in Latin America. Famed for his original use of the enlarger, chemicals, paper, and the entire development process during the 1990s, Suter has moved from physically altering the photographic image to working from data and content downloaded from the internet. In this conversation, he discusses his creative methods without losing sight of the human drama that motivates him to continue producing an eternally expansive body of work.

Although the photographic image is at the center of your work, you often use other people’s photos that you recontextualize and other resources such as video and audio. How do you define your relationship with photography, then? Do you still consider yourself a photographer at this point?

I think I have stopped being just a photographer to work with the image in a completely different way. I wouldn’t want to use the term “post-photography.” From a theoretical point of view, I could describe my recent activity by discussing the use of images that circulate on the web and are practically all in the public domain. What interests me are images devoid of the idea of authorial photography. I am interested in recovering the essence of photography or, in any case, of this type of image, which are documents without artistic pretensions, visual documents that I think are very important to examine and reuse. My work has traversed many places in photography. And always – although it is another word I don’t like – in experimentation with the image. But what I do now has little to do with the photographic purity that I may have adhered to in the 1990s, that idea of constructed photography. In my recent projects, I have set aside my authorial character as a producer of primary images to be more interested in being a kind of image collector. And what also interests me is building narratives that put contemporary ideas in dialogue with stories from other historical periods. In neoTrópico, for example, there are many references to Fray Bartolomé de las Casas or Theodor de Bry’s lithographs.

NeoTrópico is a unique project in your production, as it encompasses or is thematically related to several of your other recent works, such as the series Origen y Destino. What interested you in developing this project?

NeoTrópico is a compilation of violence in Latin America, mainly linked to forced displacement. I intend to construct timeless stories, insisting on the repetition of many events and the continuous violence towards the population in Latin America. And the violence that often has to do with extractive strategies, economic problems, or organized crime.

I use photographs of migrants or records made by security services in the countries. They are often images produced by “migrant hunters” on the border between Mexico and the United States. To a certain extent, they are images that are clandestine or sneak out of the migration service: night shots, infrared shots, shots made with drones, or with the cameras that police officers sometimes wear on their chests. They are usually very raw, first-hand images. And once they are released and begin circulating on the internet — which generally involves some infraction or crime — those documents have no authorship, or when they do, it is that of the institution that produces them.

For example, I was recently struck by images from El Salvador. It’s impressive: the transfer of two thousand “gang members,” as they call them, to a high-security prison with 40,000 people. The photographic record shows the entire transfer and all the work of subjugating the prisoners: we see them handcuffed, shaven, in white underwear, unable to walk upright. And these images are being produced by the government of El Salvador itself.

“It seems to me that post-photography is an invention of theory to justify many things that, for me, are inconsequential. Discussing whether something is or is not post-photography does not interest me. The problem is not there; it is not a theoretical problem; it is a problem of substance, of how photographs are being used, and what they are for. So I think the discussion, at least now, is useless to me.”

How did this project start, and where does your interest in migration come from?

Since working in photography, I have always been linked to historical themes for many reasons. One is my education: I studied political economy at a public university in Mexico. My primary field of education and approach to reality is the social sciences. Another reason is my history as a migrant: I was born in Buenos Aires and came to Mexico in the seventies; I have been living here ever since. So there is a personal matter of seeking to understand, as Facundo Cabral would say, that “I am not from here nor there.” Migration also interests me because it coincides with powerful political moments in the region. Not all exoduses are linked to the project of finding a better life, but often there are urgent political reasons to migrate.

On the other hand, reviewing my other projects, they all have little to do with this topic. In the late nineties, I was awarded a Rockefeller grant to develop a project related to the use of a container and questioned what happens at the Mexico/US border. That project, called Transitus, was the first straightforward approach in my activity to migration. Later, in 2015, I did another project at the Vigo Photobiennale in Spain, where I worked with a container and X-rays that I collected in a hospital in Galicia. What motivated that second work was seeing on the news in 2011 X-ray images of two containers carrying 513 people, taken at the Mexico-Guatemala border by the migration service. That terrible image triggered a series of ideas in me from which I began to build, and it has been expanding.

Finally, in September 2017, I had a planned installation at the Laboratorio Arte Alameda here in Mexico, which would be a new exploration of this topic. Still, it coincided with an earthquake, and the exhibition had to be suspended. That was the somewhat accidental birth of neoTropic. It was an exciting opportunity because I had just completed my doctoral thesis on the notion of “expanded image,” This was the first time I was going to put that idea into practice.

That has to do, among other things, with putting photographs without authorship in dialogue. Tell me about the micro-stories that you composed based on that material.

These micro-stories are part of a book that has later jumped into the exhibition space in different ways: as an object, as well as projections, or as large-format photographs. Now I am interested in developing the performative aspect of telling the stories and presenting the project in different forums with different audiences. This means that neoTrópico is not only the book or the exhibition, but it encompasses all the media that allow me to build and enrich the narrative.

I imagine you came across images that surprised you among those taken by the migrants themselves.

Of course! For example, where else will I find images of migrants cramped inside trucks or of how they travel hidden in a vehicle? Everyone has a cell phone. In the shelters in Mexico, there are tables full of power outlets where they plug in their phones. It’s the first thing they do when they arrive because it’s how they communicate with their families. And often, they sell the photos to Associated Press, Getty, or Reuters. They are unmistakable images because they have the 16:9 cell phone format, which full-frame cameras do not have. And you see that they are not photographers because they do not care about aesthetics or the decisive moment: it is a record with a different meaning. But they are vital images: among other reasons, because no journalist could have taken them.

That makes me think of another project I have, based on the news of the abandonment of a trailer with forty-eight teenagers locked up in a place in the jungle of Mexico. They, fortunately, managed to get out, and there are images of these people sleeping in the middle of the jungle. Who took those photos, if not them? All that material is like an omnipresent, all-powerful eye constantly recording them.

“For me, there are two parallel worlds: the virtual world and the real world. In the virtual world, things happen very similar to the real world, but I can’t photograph them. What I can do is take screenshots. And that reality that moves slightly differently also needs to be captured; we need to know how to find the decisive moment of what is happening in that other dimension.”

I would like to go back to the topic of post-photography. I am curious to know why you avoid using that word.

I think post-photography is an invention of theory to justify many things that are inconsequential to me. Discussing whether something is or is not post-photography does not interest me. The problem is not there; it is not a theoretical problem. It is a fundamental problem of how photographs are being used and what they are for. So I don’t find the discussion helpful, at least at the moment, even though I wrote a treatise on it. [laughs]

Well, that’s curious, that’s why I’m asking you.

I am more interested in the practice. But there are theoretical questions that I find important. Ultimately, authorship is being questioned: to think that the photographer is only the one who clicks is a bit limited.

And yet, you no longer consider yourself a photographer.

Well, look, I take screenshots. But I have training as a photographer, which informs my work when I recompose the images. It’s something I’ve learned over many years. In that sense, I’m not so interested in the moment of capture itself but in the post-production moment, the space where post-photography moves, that second moment many critics have called the “second shutter.”

But the moment of capture, which I moved away from for a long time, has started to interest me from another angle. For me, there are two parallel worlds: the virtual world and the real world. Things that are very similar to the real world happen in the virtual world, but I can’t photograph them. What I can do is take screenshots. And that reality that moves slightly differently also needs to be captured; you need to find the decisive moment of what’s happening in that other dimension. That’s the space where I’m interested in working now.

Are you interested in the use of images generated by artificial intelligence at all?

Among the curiosities I do, I coordinate a graduate program at the university, and some of my students have started working with these technologies. Let’s say that I resist a little leaving the creative process in other hands – or other circuits or different algorithms. I believe that is the last thing we have left as human beings, so I am a little scared of the idea of something thinking for me, creating for me. Also, images made with artificial intelligence do not interest me because they are not real, and I am increasingly interested in reality. How we capture it doesn’t matter. But we need to recognize reality in some way. In my opinion, those artificial images that could be considered within the spectrum of post-photography have more to do with post-truth. They are not at the level of creativity, at least not yet, but are at the media level, where it is essential to determine what is true and what is not, what happened, and what is an illusion.

Maybe I’ll change my mind. I have a student who is working on his origin as a mestizo in a town in Mexico; for that, he is interviewing his grandfather, who tells him stories of which there are no photos. So, based on that story, he is producing images with artificial intelligence. I have seen the result, and I thought they were photos he had taken with a 6-by-6 camera. They look outstanding; they are black-and-white images of some fields in the United States where his grandfather worked. There, the use of this technique may make sense. But then I think about the dangers of this being used in another way and of us losing control. Not only because it is a technology that lends itself to manipulation but also because I am worried that producing ideal images will make reality unnecessary, making us unaware of it. That’s why I’m so interested in using photos that are not even intended, that move as far away as possible from the notion of authorship that contaminates the world of the image.