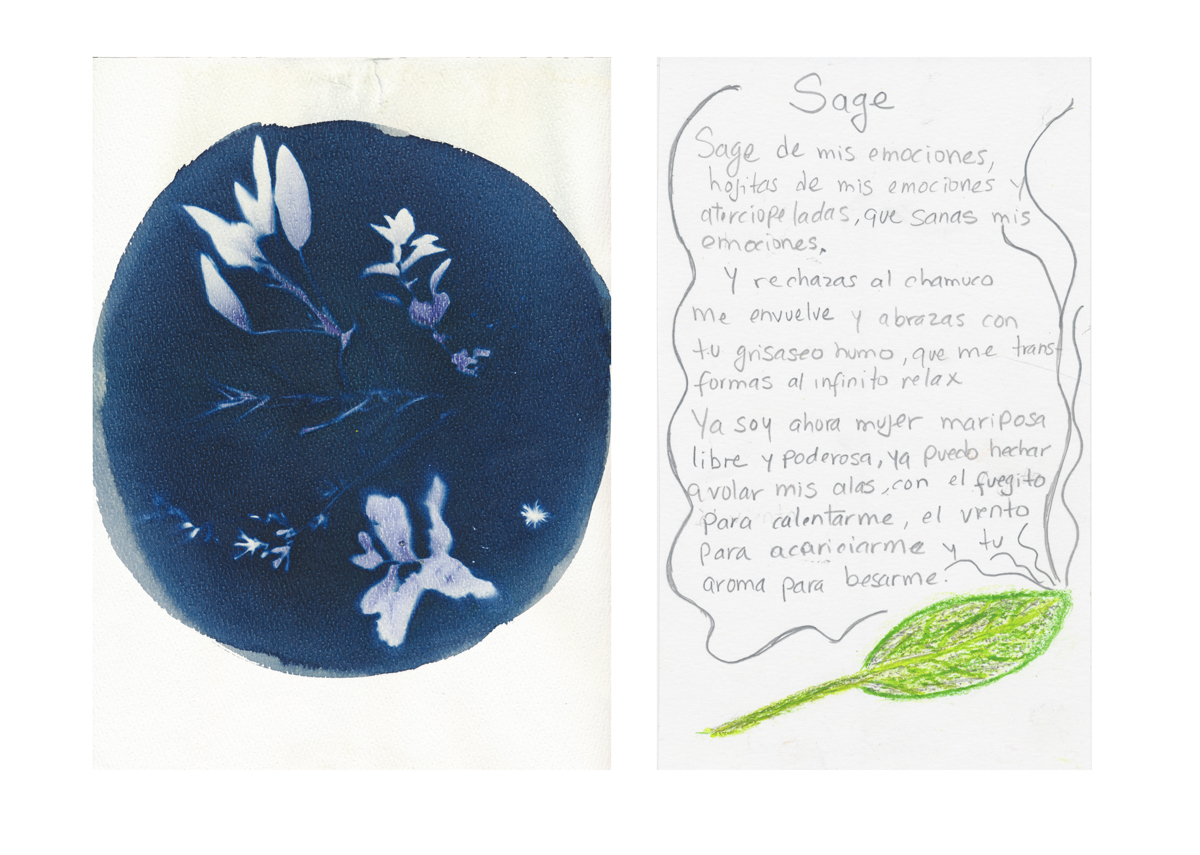

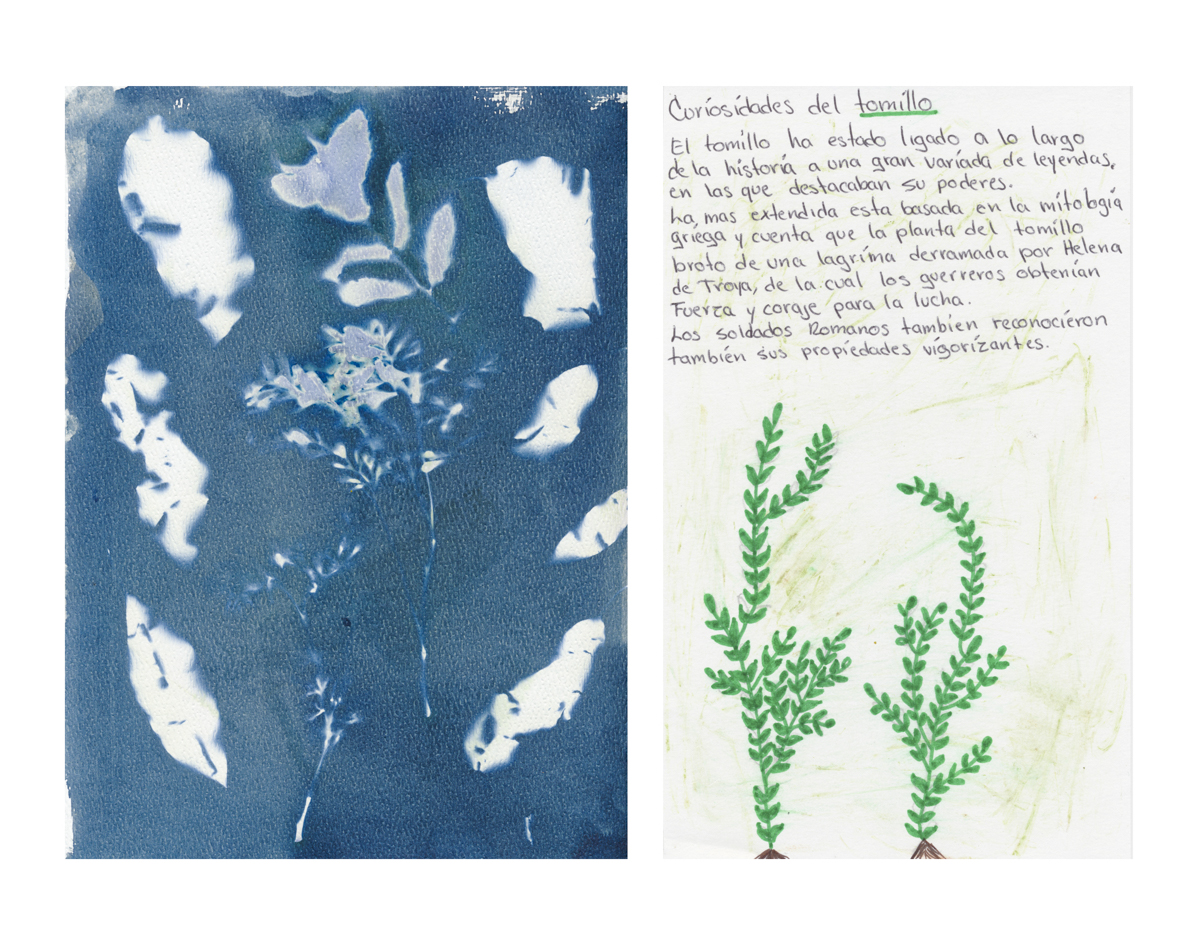

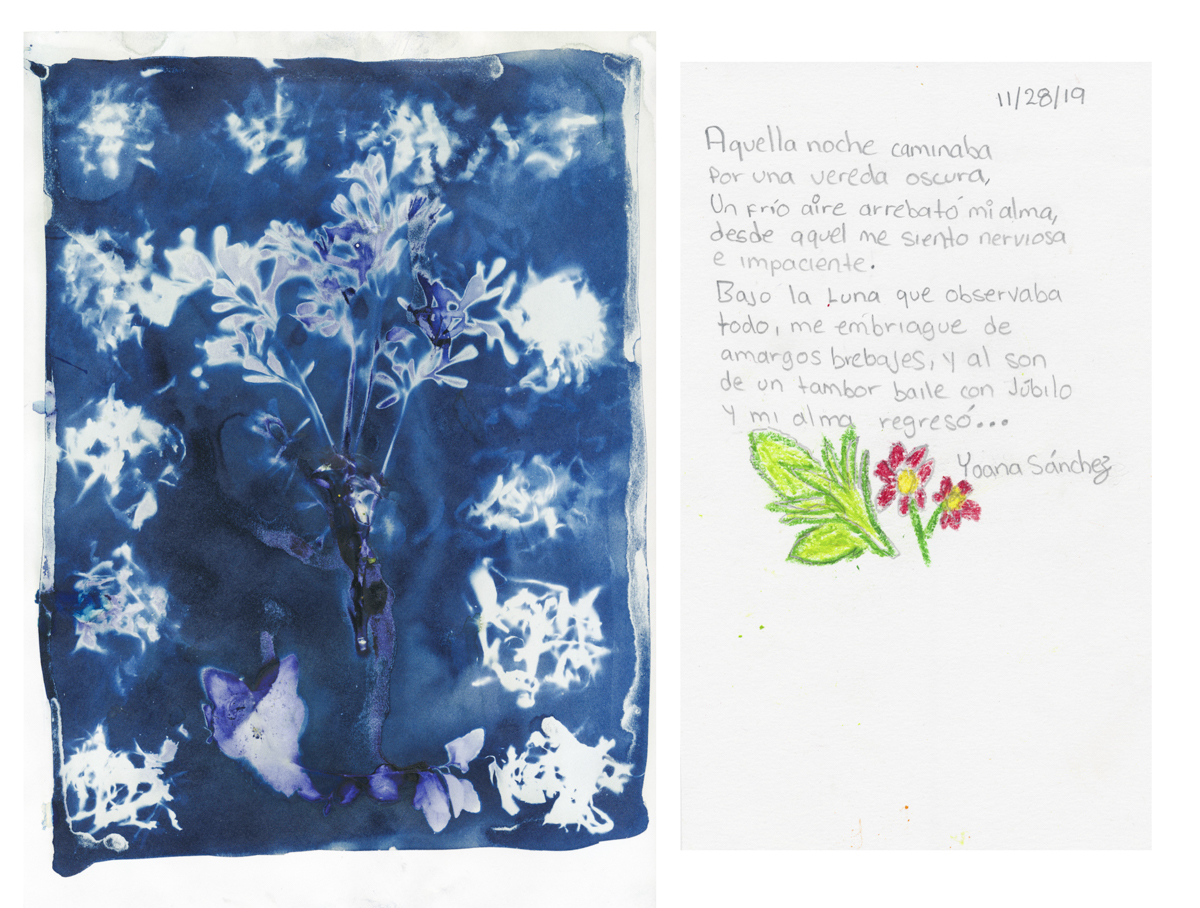

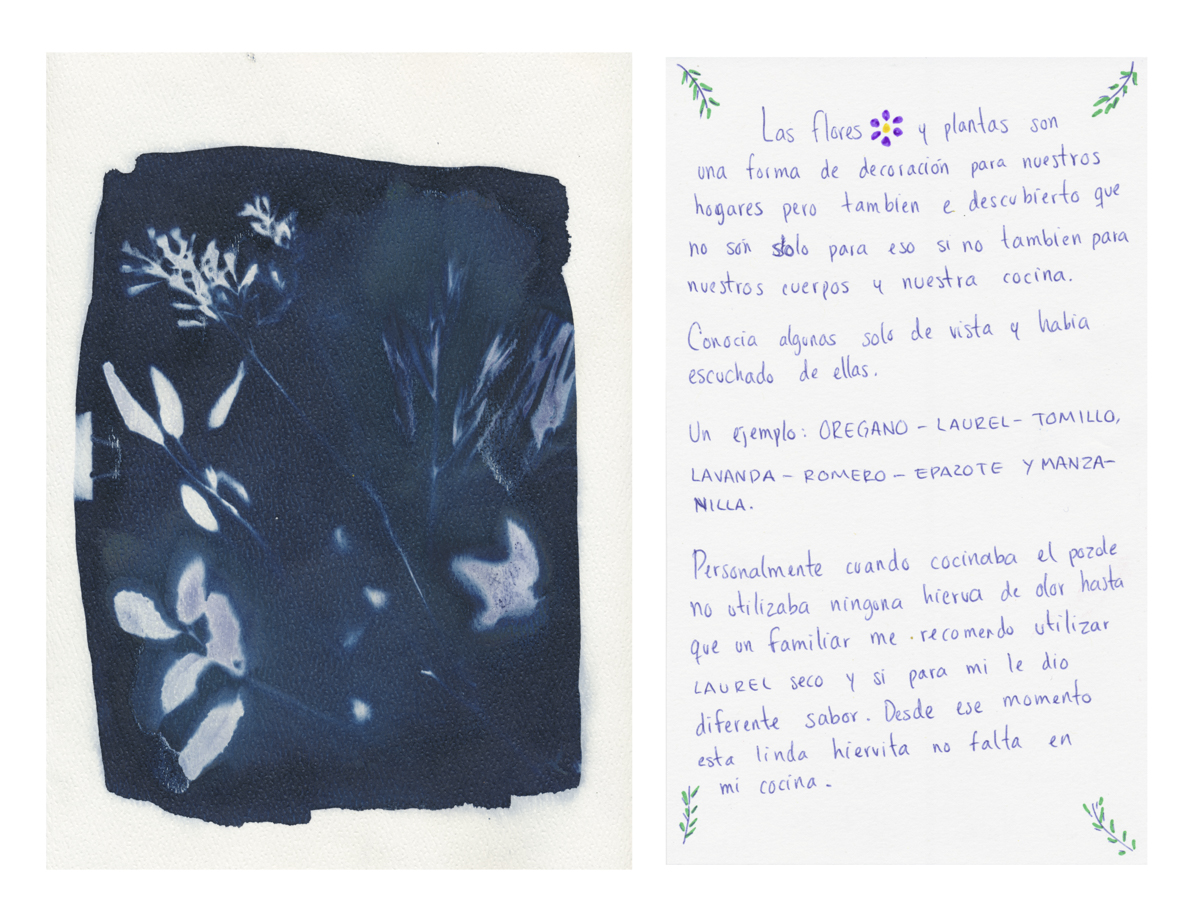

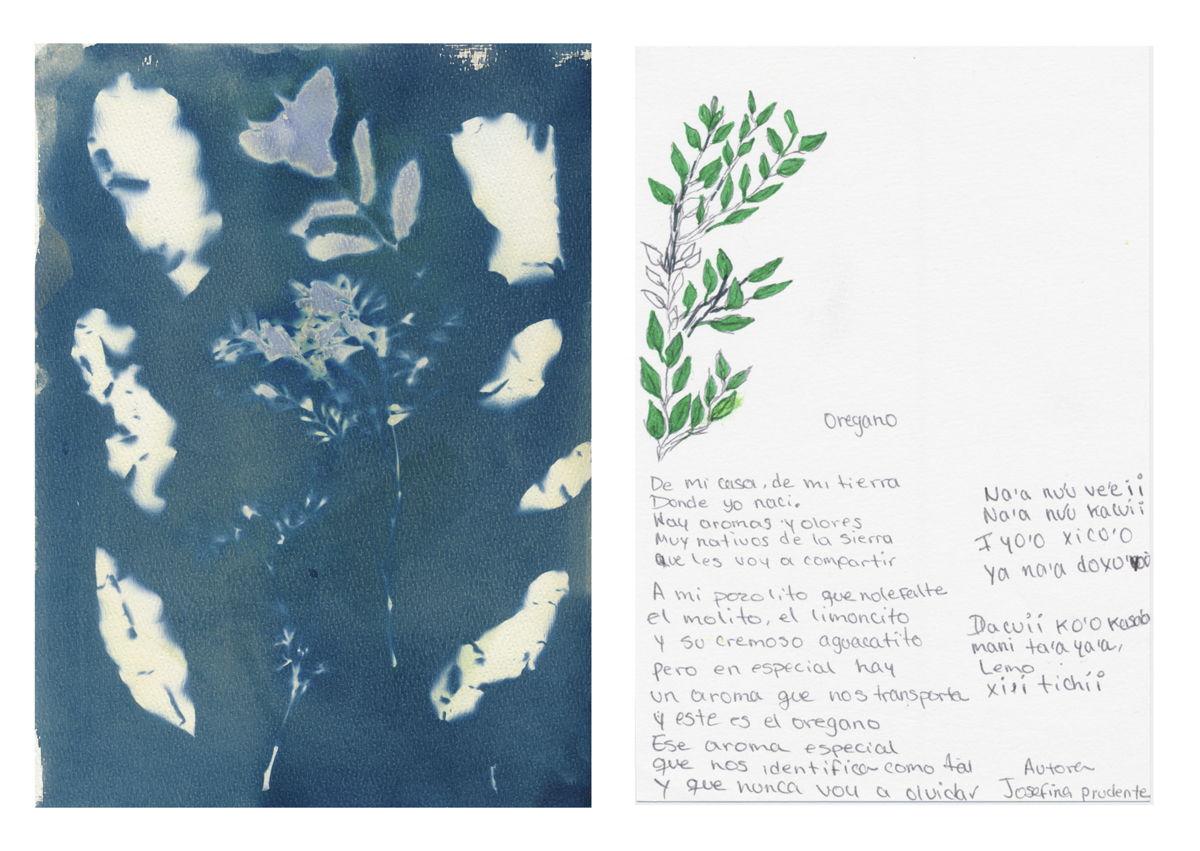

“I remember seeing my mother and my grandmother; they used arnica, chamomile, rose, avocado leaves, thyme, oregano and other species ”; “Oregano from my house, from my land, where I was born”; “Rue for menstrual cramps in tea.” The sentences are written by hand, in pencil, on paper. They are accompanied by a blueprint. The event was called Migrant Herbalist and in it different Mexican women told how they used herbs to heal their families. It was a workshop on “herbs, migration, memory and healing”, Cinthya Santos Briones tells Vist Projects.

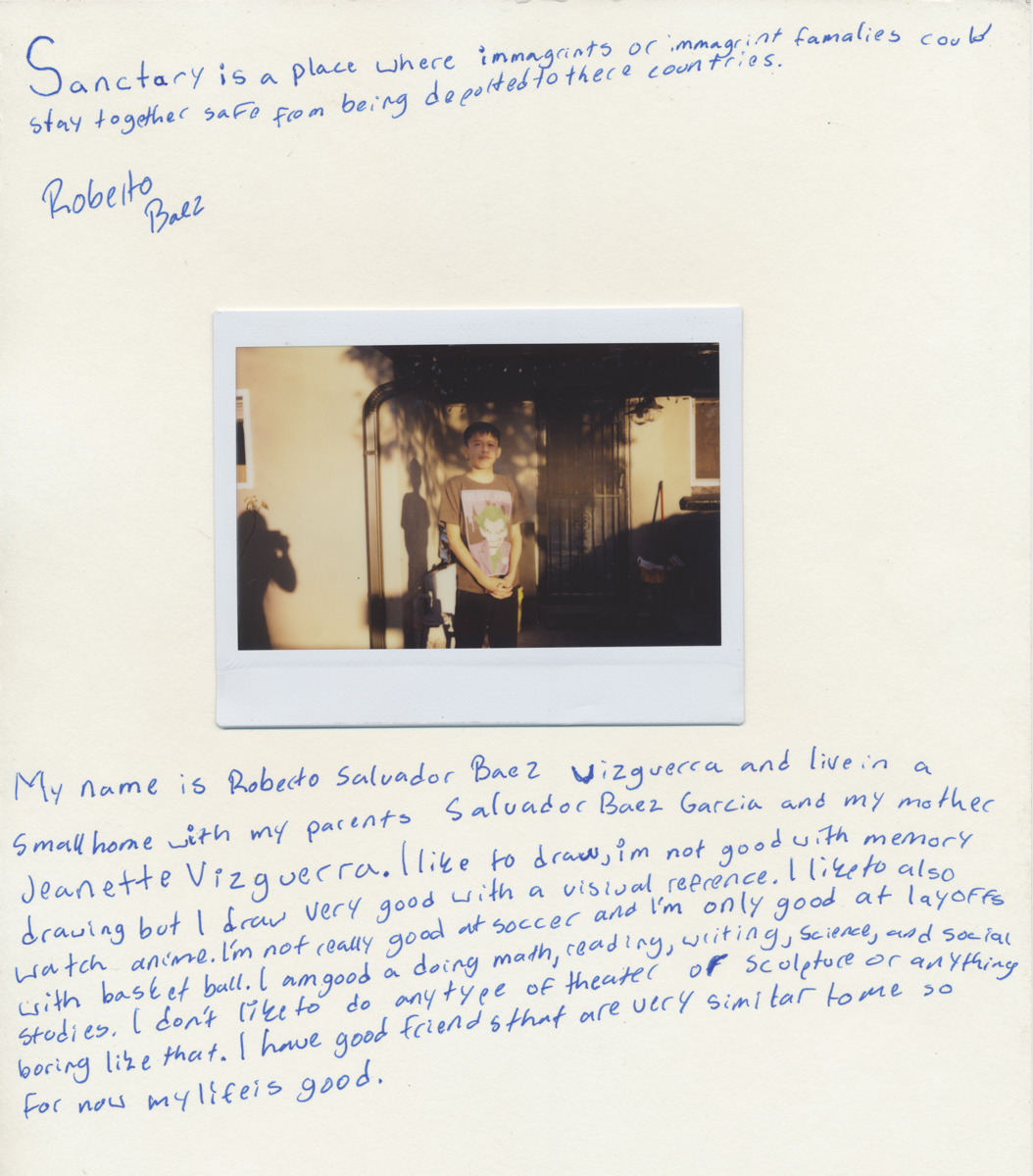

She is a photographer, anthropologist, ethnohistorian and lives in New York. She usually works on migration, memory and identity. She is interested in the struggle for control of symbols and identifies that there is an asymmetric relationship between photographers and photographed. She is especially interested in self-representation and that is why she usually plans paths in which play with others is possible. That’s why she asks migrant grandmothers how they want to be photographed, she asks street vendors to write their stories on paper or the inhabitants of a sanctuary to draw a drawing by hand.

Cinthya also directed the documentary on the Huichapan Codex in which she tells the story of these ancient documents. It is that she began her journey from anthropology and trips “to the territory” in which she took her first photos. Over the years she changed her perspective. “The training I had in social sciences has limits, it doesn’t allow you to explore metaphor or conceptuality, and art does,” she reflects.

How did you start with photography?

I studied anthropology and history. There I was trained in an ethnography project that sent us to the field. It was divided into several regions of Mexico, each group took one to study it. Every time they sent me, I worked on interesting topics: rites and worldviews, interviewed healers and shamans. The first few times I took a camera borrowed from a cousin, those digital cameras from 2004. Through taking a photographic record so that those photos would help me tell that story visually, I realized that it seemed fabulous to tell from the visual the ethnographic. It was a curiosity that was born there, but had never deepened it.

Until now, after a while, I found out that I wanted to go back to school and explore other disciplines. And it was photography. I then studied photojournalism and documentary photography and trained in technical terms. And also in terms of thinking about the study topics in a visual way, which is different from thinking about them in ethnographic terms.

How was that shift?

It was difficult, because when I entered I was thinking like an anthropologist. The teachers told me that some things that I wanted to work on at the time were not visually understood. Honestly, it took me a while to digest what visual language was all about. It has been a gradual process and over time I am rediscovering new forms.

Now I am studying a master’s degree in text and image that focuses on the photobook. I am reading a lot of conceptual poetry, a poet like Juan Tablada who makes poetry in forms and those forms are images. It is like rediscovering from art and moving away from that rigid approach to the social sciences in which I was trained. Social science education has limits, it does not allow you to explore metaphor or conceptuality, and art does. It is open to experimentation, feelings and not being objective at all.

How do you choose what to tell? Is it linked to your personal history?

Through the books of photographers that I admire, it seems to me that many people work on the familiar. In my case it was different, I started talking about the others. Although it is true that there is a relationship: talking about migration has to do with my family history. My family emigrated to South Carolina in the 90s and they were undocumented for a long time. That separation made me very aware, since I was a child, of different categories: being illegal, undocumented, not having papers, not being able to move through the territory freely. It may be something personal without saying it entirely.

You have an interesting work on the Abuelas…

Abuelas was the project I graduated with, it is my first visual project. When I migrated in 2011 I was working as a community organizer in different neighborhoods of New York and I got to know many people from the Mexican and Central American community. I had to bring a proposal to the school and I had nothing. A friend asked me if I could take a picture of her to send to her grandchildren that she doesn’t know because they are in Mexico. And I came in and took her photo and I found it very interesting the way she wanted me to take the photo.

I wanted to create a methodology in my work, I did not want it to be one more that documents migration, since it is a phenomenon that is over-documented. Through seeing that agency I began to discuss the term of the subject, a very colonial term that we use in anthropology to refer to the people we investigate but who collaborate with us. People with agency about their decisions, about what they decide to share or tell.

The project came out with that: the reflection on the agency of the people that one photographs is a collaborative project. I ask them how they would like to be seen.

I wanted to talk about old age. They are all grandmothers, they all have grandchildren, but not all are over 60, nor are they gray or wrinkled women. I wanted to speak from this reflection of how difficult it is to be an older and undocumented woman. Many are domestic workers, babysitters, or work in stores as cashiers. Or they have multiple jobs.

I was also interested in the territory: how from a small space in their homes they rebuild their culture, hang their memory, the relationship they have with the space they inhabit, knowing that they have no papers. There is a relationship with objects and their meanings, that baroque relationship that we Mexicans have. Every time I entered these houses there was a universe, an ethnography of the room, counting those objects that give life to that space.

And how did they want to be displayed?

Basically, I would arrive and they had various clothes, very elegant. One has a shirt of the 43 students who disappeared in Guerrero. They controlled everything, they were agents. It was like they were hiring me. Suddenly there was a toilet paper in the frame and they told me that I had to remove it because it was not going to turn out the way she liked it. They were thinking about where to put the light.

Did you discover the idea of developing collaborative projects or did you bring it from anthropology?

Some time ago I made a documentary on the Huichapan Codex, which is the only one made in the Otomí language. I did it in collaboration with the editor but also with a language speaker to make the documentary with us in his own language. Because the codex speaks of a particular region.

In the academy we usually deal with such specialized topics and sometimes hardly digestible for those who do not study them. I found it interesting to make these documents known. I spent two years studying in the archive and found it fascinating. But people don’t know them. Many of them were burned but the ones that are there must be known. So then I said: we are going to film the documentary in the region, within the communities, and let them hear it in their language, not in Spanish, which has been an imposed language.

Later I edited a book in collaboration with a friend: textiles and cosmovision, in a community where an uncle of mine is a rural teacher. With the children who draw stories about the symbols on the textiles that their mothers embroider. That was my most representative work before the image. I always tried to put authorship in dispute.

From that point of view, you also address the work you did on street vendors, where you include a note written by them, right? As in Leecatzin.

I really like that in each writing there is a different calligraphy. Asymmetrical relationships are generated in interviews, so it seemed to me that it was better for people to write. I give them an idea and after that they do their own analysis. There is a lot of agency in that sense.

As for the herbalist, there are many herbs that we find in the United States that come from Mexico and we seek to rescue that ancestral Mexican memory. In addition, we thought about how to create spaces for community art. Leecatzin is a blueprint workshop that I gave with a friend, a traditional indigenous herbalist. We gave the workshop on herbs, migration, memory and healing. With that knowledge, the women wrote poetry. Or recipes. Or some tales or stories that they remembered that their grandmothers told them. With these plants we made blueprints, they learned the technique. I scanned them, we printed them and made some photobooks. They sewed, painted, intervened and an exhibition was made. The idea is to see migration from another point of view.

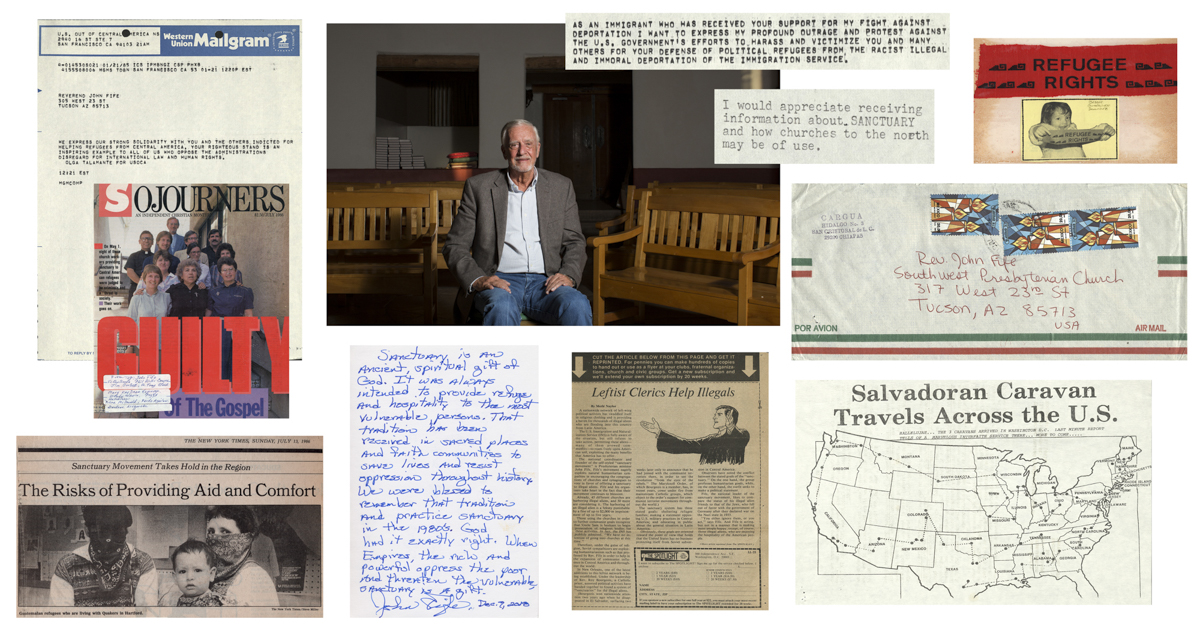

You also face, in another of your projects, the sanctuaries in the United States …

Since I arrived I have been involved in activism and I have been working as a volunteer in an interreligious organization that is in charge of stopping deportations, of fighting so that families are united, of avoiding the incarceration of migrants. I worked a lot with the Honduran Garifuna community, which experienced a great exodus of women who came with their children and many had an electronic shackle attached to monitor them.

The sanctuary movement began in the 1980s with a group of priests across the United States helping refugees fleeing violence in Central America. They helped to give them sanctuary, to provide them with a welcoming space in defiance of anti-immigrant laws and US policies. In 2006 or 2007 a new wave emerged, which also followed these same principles of giving sanctuary to migrants.

In the United States, there was a memorandum that states that the immigration police cannot enter neither churches nor hospitals nor schools. My husband was undocumented and is the co-founder of one of them. He is a Lutheran priest, he was involved in the movement of justice and human rights of migrants, very much from liberation theology.

That’s where I started and I found out that a friend was going to take sanctuary, Amanda Morales. She publicly announced that she was taking refuge in a church because she had a deportation order and that from there she was going to appeal her case. She spent a year in this church in Manhattan. I went to support her, without even a camera. Later I told her about this idea of following her and photographing her, of telling her story. I showed her my work, to see what happened. And so it happened.

But at one point the work was already very repetitive, since the scenes were very similar. So I decided to expand it to other parts of the country. I wanted to talk about other non-Latino immigrants because the media focuses a lot on them to talk about deportation and detention. What I would include in this work, for example, an Iraqi refugee, another from Indonesia. I traveled to document but also asked them to write about what it meant to them, what it is like to be locked in a church.

For this project I got more into the archives. At that time it was a big topic in the news, also Trump had reached the presidency and the laws were more severe, more crude. It is thought that during his tenure the racist anti-immigrant policy of this country was exposed a lot but it has always existed. Now there is more media attention, Trump made his anti-immigrant position more notorious but that already existed and this can be verified through that file.