Open images of Latin America

Pietro Paolini was born in Florence (Italy) and has been traveling around Latin America since 2004. He looks for “non-closed images” to open questions. After more than a decade of building the book Looking for Bolivar, he is now working on a project about how cryptocurrencies are growing in Venezuela, where he lives. He also wonders about the various forms of representation through contemporary images. He won second prize in the “Everyday Life” category of World Press Photo 2012 for his work in Bolivia and is part of the Terra Project collective.

You found some ethnographic photos, how was it?

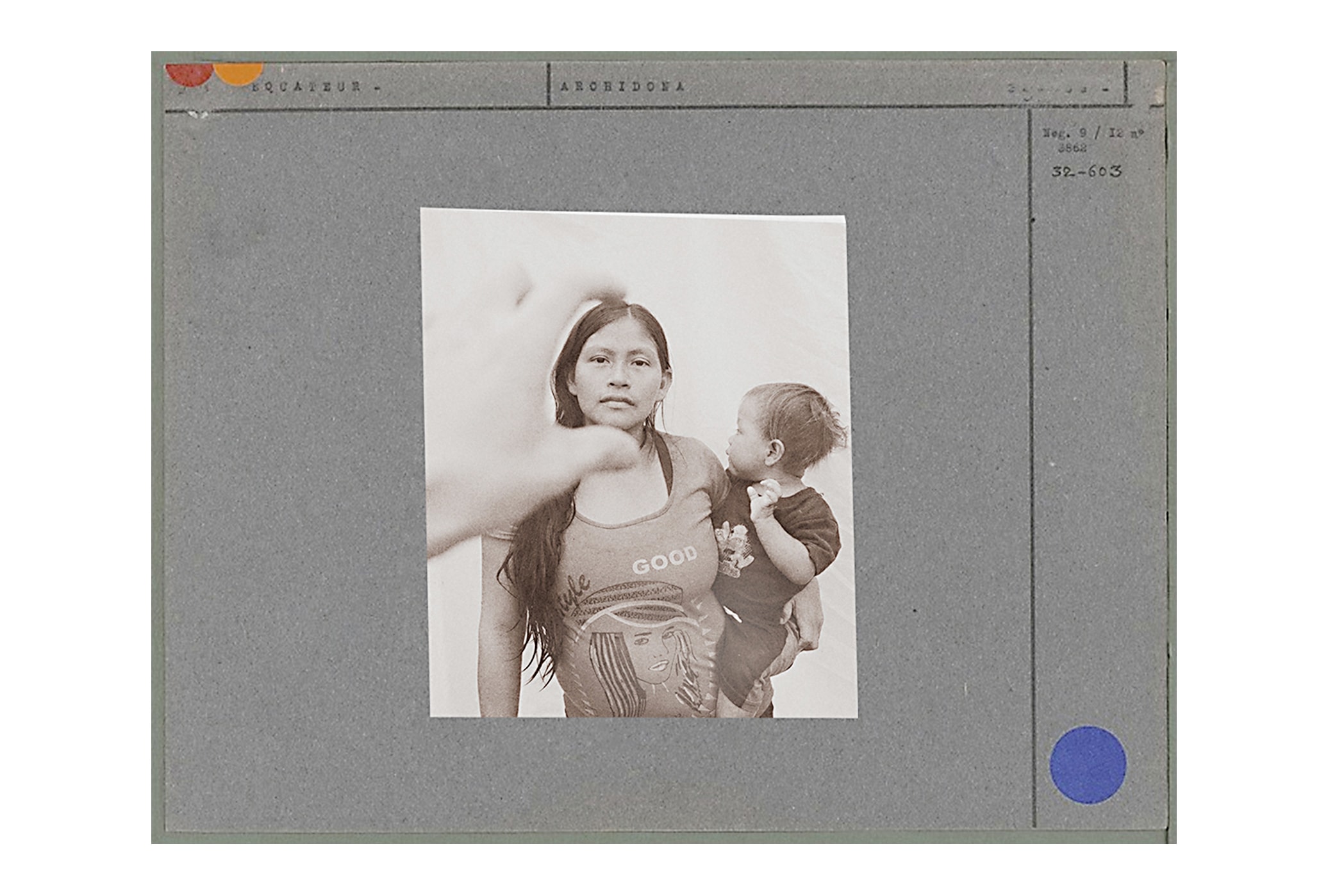

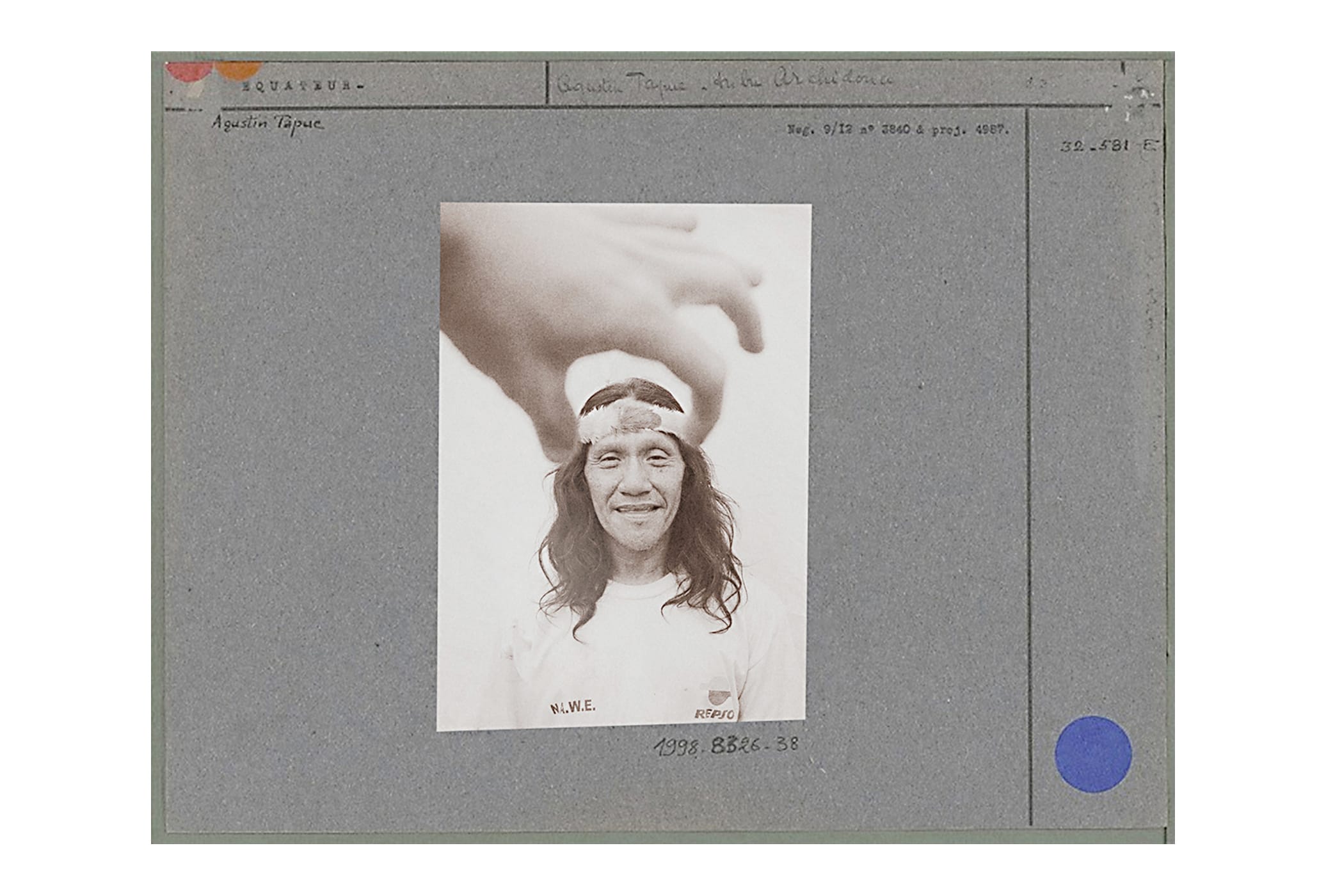

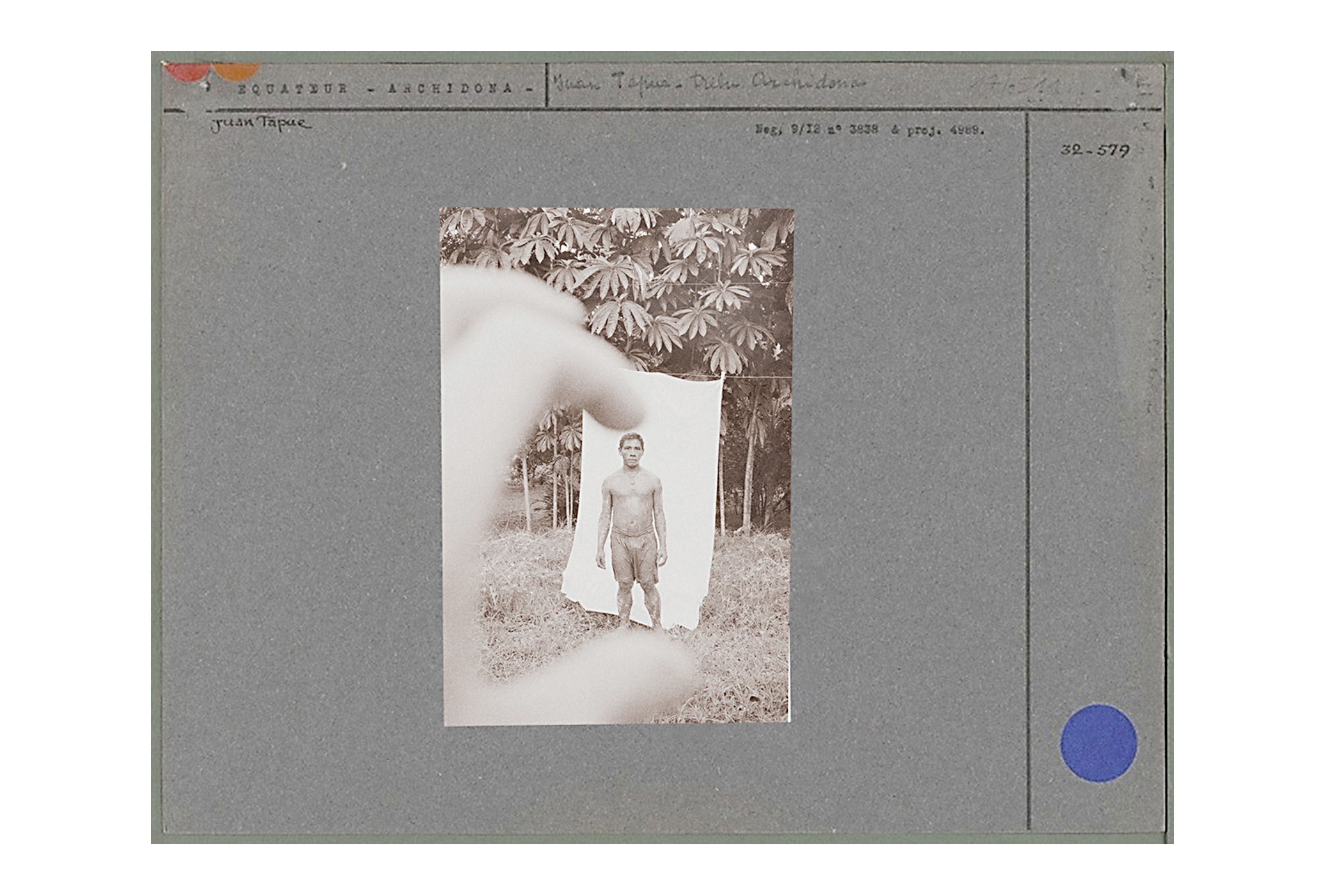

Those are the files of an anthropological photographer that I found in the Paris museum. Then I took photos intervened with those fingers in a protected area of the Amazon in Ecuador. That led me to a reflection on the history of European ethnography, in which there was a way of representing, extraction of the context, the white background. It looked like someone coming from outside, like a spectacle, like something unattached. It was squeezed out as a superiority. I am exploring the clash between ancient representation methodology and contemporary images.

Being yourself a European photographer, how did you deal with that debate in your daily work?

My first job was in Caracas in 2004, I came with one of the first digital cameras. In two weeks it broke. Coincidentally, I had brought an analog Rolex, I started taking pictures and never moved from the medium format. In the first years, I explored Chavismo and popular organizations with a classic documentary journalistic look. I would go to festivals in France and what I saw most from Latin America was violence, the gangs in the slums. They had a very stereotyped image, and I decided to overcome this kind of image. There is a complicated relationship between the continents due to colonialism, a history that we Europeans have not processed as a society. Today there are many European photographers with a different gaze and a strong wave of Latin American photographers taking their work to Europe.

How did you feel about your arrival on the continent, back in 2004?

I found myself with the duality of the representation of what was happening: there was an ongoing strong and radical process with Hugo Chavez. Chavistas told one word and opponents told another. In the international media, there were also extremes: the more leftist media presented “the great revolutionary” and the others “the fierce dictator”. I wanted to open a middle space, to produce photos that did not say “things are black and white” but complex. They are countries, period. With their contradictions and with the flow of contemporary culture. My language had developed in that search.

In 2019 you edited the book Looking for Bolívar, what is it about?

These are photographs of Bolivia, Ecuador, and Venezuela. It came out in 2019 and tells how those three countries lived through particular political experiences. It is about landscapes and daily life. It is a personal look. The three are mixed as it was an imaginary country. The cover is like an archipelago.

The three presidents (Hugo Chávez, Evo Morales, and Rafael Correa) referred to imaginaries linked to Simón Bolívar. In the 1990s, the three lived through a strong neoliberal policy that led to a very high political conflict: the gas war, the water war, the Caracazo. These presidents rode the wave of these social movements and promised radical change. Another similarity is that very beautiful new constitutions were written in a participatory way. They were then neglected. For example, Ecuador contemplates the rights of nature. They also continue to exploit Amazon.

The book has a lot to do with something dreamlike, with the hope that these people had for something better. There were a lot of charges, positive energy, dreams of something better. On a personal level, that appealed to me. Europe was without a vision of the future, it was repeating itself, in pause. Here everything was moving, everything was changing. Some things changed and some things didn’t. But there was a dream. But there was a dream and, in the end, that’s what makes you walk.