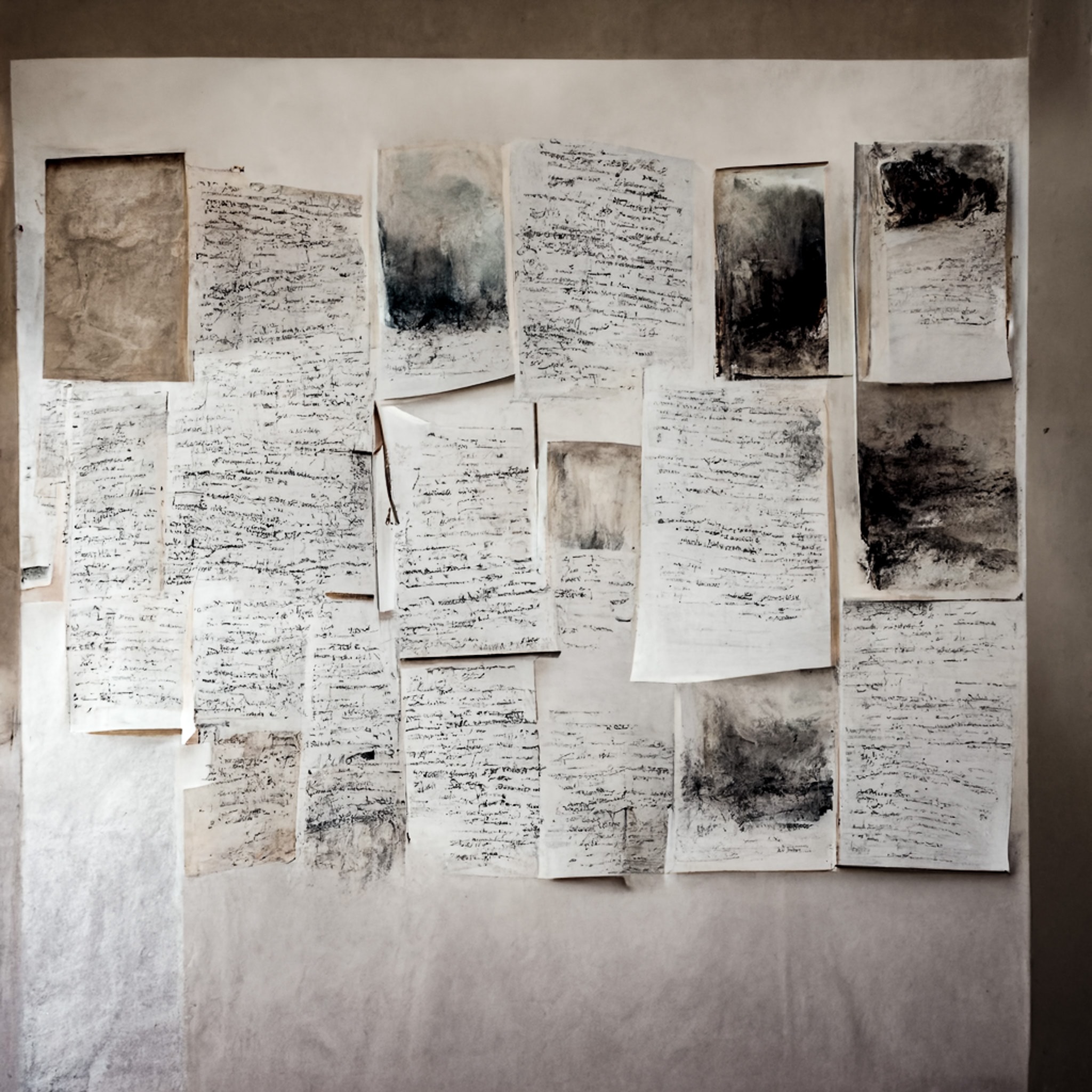

“Popular photography is on its way to becoming something different: something between photography and painting.”

Lev Manovich is considered a world authority in the digital humanities field and new media aesthetics. In this conversation with VIST, the Russian academic and artist maps the evolution of his ideas since the publication of the classic volume “The Language of New Media” in 2001. He also discusses his experience as a visual creator using artificial intelligence tools and outlines a fascinating panorama of the future of photography.

By Alonso Almenara

Two women from different generations pose one behind the other, the elder hiding behind the younger. The black-and-white and sepia-toned image, ‘Pseudomnesia: The Electrician,’ went viral in April of this year. The reason: its creator, Berlin-based artist Boris Eldagsen, won the prestigious Sony World Photography Awards in the Creativity category with it, a prize he later rejected after admitting that his work was a provocation created with the help of an algorithm. The experiment tested what many photography professionals have suspected for years: very soon, thanks to programs like Midhourney or Dall-e, it will be impossible to determine if a photo has human authorship or has been entirely created using a camera. The apocalyptic tone of the comments generated by this news is, in fact, reminiscent of the controversy that has gripped the American film industry. Recall that Fran Drescher, the spokeswoman for the Hollywood Actors’ Guild, described artificial intelligence as an “existential threat.”

Lev Manovich, however, sees things differently. For the most cited author in academic fields such as digital culture, digital art, and cultural analytics, according to Google Scholar, those technologies represent the exact opposite: a kind of personal liberation. In his words, these tools have allowed him to “travel back to 1989,” the year of the Berlin Wall’s fall, when Manovich abandoned his artistic career to dedicate himself to academic research on a new phenomenon: digital culture.

Born in Moscow in 1960, Manovich witnessed the final period of the Soviet regime, an experience that would shape his understanding of the development of cyberspace in the 1990s. Distancing himself from the rampant optimism that characterized the discourse of Silicon Valley’s tech gurus, the Russian author even described the early days of the internet as “a communal apartment from the Stalinist era, where there’s no privacy, everyone spies on everyone else, and there’s always a line for common areas like the bathroom or the kitchen.” But this critical approach was complemented by detailed descriptions of the functioning of the prevailing technologies. For example, Manovich was the first author to formally identify and analyze a series of crucial tools or processes (which he called “operations”) in all kinds of commercial software, from word processors to video editing programs. These include conventions like copy and paste, search, delete, transform, etc.

The impact was enormous: Manovich’s first book, “The Language of New Media” (MIT Press, 2001), was translated into thirteen languages. “Having grown up in Russia, completed his higher education in the United States, and lived and worked here since then, he sees the world through the eyes of what he calls a post-communist subject,” writes American artist Mark Tribe in the introduction. “But it could be equally accurate to say that he also wears the glasses of the new world.”

Since then, Manovich has continued to delve into the study of contemporary digital culture. In addition to publishing numerous books and articles, he is a professor of computer science at the City University of New York’s Graduate Center and a visiting professor at the European Graduate School in Saas-Fee, Switzerland. His most recent book, “Cultural Analytics” (MIT Press, 2020), results from his leadership at the Cultural Analytics Lab, the first initiative for computational analysis of massive collections of images and videos.

“In 2003, digital arts exploded,” he recalls. “Tools became more accessible, computers became faster, and the number of digital artists grew exponentially. So, I asked myself: how can I keep up with all these people?” The concept of cultural analytics, outlined by Manovich in 2005, was related to the idea of “creating software that could connect to the internet, track the content of millions of websites from designers, artists, filmmakers, advertisers, museums, newspapers, art centers, and then analyze it in real-time. Then I imagined a massive data visualization screen where this information could be tracked. It was a sort of dashboard for global culture.”

Manovich was convinced that it was the best idea he had ever had, which was somewhat confirmed in 2006 with the launch of Google Trends: one of the early steps towards what we now know as Big Data analysis. “I was seeing the future,” he comments. But he also acknowledges that his idea was slightly different: he was interested in analyzing text and images to gain a more detailed view of global culture. In 2007, luck was on his side: a university decided to fund his laboratory. Among the projects he developed in this environment is analyzing a million pages of manga books or the evolution of Time magazine cover designs between 1923 and 2009.

Today, Manovich finds himself at a critical point in his career: he considers that the research he has been conducting so far, focused on understanding the place that new media occupy within the history of visual culture, has become “virtually impossible.” While the thematic content of images continues to generate interest, he argues that the formal analysis of visual culture has entered a decline. That has motivated the author to change course: or rather, to return to the path of graphic creation, thanks to the possibilities offered by the technologies whose development he has been obsessively mapping for the past thirty years.

Let’s talk about why, at 63, you decided to resume your career as a visual artist.

During the pandemic, I was searching and struggling in Korea with my wife. And then, one day, travel became possible again. So, in the summer of 2022, we went to Berlin, and there we found a wonderful store that sold things like notebooks, cardboard, and pencil boxes. So, I thought: maybe I can draw. I bought a notebook and a pencil. What not many people know is that my original background was in art. I studied art from the age of 12. I had a classical education and made thousands of paintings, drawings. Then I went to the Film School at New York University and worked in the computer animation industry for six years. Until I did my Ph.D. at 28, I had mainly been an artist.

But my last drawing dated back to 1989. When I started drawing again in 2002, I felt so happy, so liberated. I realized that I had dedicated 35 years to research. According to Google Scholar, I am the most cited person in five fields. And if you ask ChatGPT who the most critical scholar in Digital Culture, Digital Art, and New Media is, I always come out on top. So, I told myself: Lev, you’ve done this part. You don’t need to write more books. You can write if you want, but there are other options.

You say that drawing made you feel liberated. But you not only draw currently but also produce images with Midjourney. Does this combination of creative activities expand your intellectual exploration of new media and digital culture?

Art is a relatively new activity because I stopped practicing it for 30 years. And it’s also exciting because when I was 28, I felt at a crossroads: one path was to dedicate myself professionally to art, and the other was to become an academic researcher. I ultimately chose the latter. Now I have the incredible opportunity to come back and explore a different path.

But, of course, that doesn’t mean I’ve forgotten how to write or think. In the past year, I’ve been posting many of my images on social media, and often, alongside the photos, I post short texts with my real-time reflections on AI as an artistic medium. In fact, with Emanuele Arielli, a colleague, we are writing a book about art made with AI [Artificial Aesthetics: A Critical Guide to AI, Media, and Design], and we are publishing the chapters online.

So, in reality, I’m not writing less than before, but I have this other activity. For me, creating images is much easier than editing articles or writing books, and it’s very pleasurable. It’s also a different way of reflecting on the world. There are more possibilities because you can address emotions, psychology, subjectivity, and humor, whereas academic writing is more limited.

“Let’s say you have ten ideas for a painting, but you have limited time and can only explore one idea. Now, with Midjourney, you can explore ten ideas in a single day. Sometimes you find the right prompt and generate 400 images in one night. It’s like having a thousand assistants who know everything about the history of culture. The challenge is that if you let them do whatever they want, they start creating clichéd, cheesy art. The struggle is to make these tools do something subtle and unique.”

What features of Midjourney or other AI applications are you interested in exploring in your visual work?

I’ve witnessed the emergence of various digital technologies in my life, and each time I felt like a whole new world was opening up, I wanted to explore it. In 1982 I saw the first computer-generated animation and said, “Someday, these computer-generated 3D images will be as popular as photography.” And I was right. Then, of course, the World Wide Web came in 1993. And in 2005, something that later became known as Big Data emerged. Then came the iPhone.

Like many people, I was amazed when I first saw Midjourney precisely a year ago. The results weren’t as good as now, but they were already impressive. It’s an incredible tool for an artist because it might take you days to create a complex drawing or painting. Let’s say you have ten ideas but limited time, so you can only explore one idea. But now, you can explore ten ideas in a single day. Sometimes, you might find the right prompt and generate 400 images in a single night. So, it’s like having a thousand assistants who know everything about the history of culture.

But the problem is that these assistants are a bit stubborn. They’re young and don’t have very good taste. If you let them do whatever they want, they immediately start creating art that’s clichéd, stereotypical, cheesy, and so on. So, the main struggle for me is making these tools do something subtle, nuanced, and unique.

Why do these technologies default to generating stereotypical or common results?

Machine learning is based on a particular understanding of information. You feed the machine with billions of images and descriptions, and it extracts common composition patterns, shading, and more. But if something happens very rarely, it won’t capture it. That means when you create images, they can look beautiful, but you always feel that you’ve seen them somewhere else. That is a big dilemma for me: on the one hand, I can realize thousands of ideas in a week, and the images are beautiful, but then I look at them and notice these subtle but very disturbing generic elements.

So, I’m finding ways to fight against that. I’m using mid-journey now because I write a prompt and include images as inputs. The AI can get confused if you use completely different images—for example, one of my drawings, an 18th-century engraving, and an abstract painting. And when it’s confused, it produces strange results. On the other hand, by providing specific examples, you can guide Midjourney toward something more specific. Sometimes I don’t even write a prompt; I just give it some images. And then, the AI acts as a kind of remix machine.

At the same time, I’m creating drawings, going back and forth. It’s difficult because drawing takes much more time, so I must force myself to do it. But I believe doing both things simultaneously helps me better understand how these tools work and what this medium does. It also helps me better understand what makes drawing or painting unique or the creativity of humans. So, I’m making art, but I’m also conducting experiments to understand and write about it.

Recently, you posted a text on Facebook stating that “discussions about aesthetics have become nearly impossible in the United States.” Why is that?

The truth is that it was a somewhat exaggerated post to draw attention to this issue. Of course, other people have written about it. In the mid-1970s, I surveyed university professors in the United States, asking them: are they on the right, left, or far gone? Around 35% of professors at that time said they were leftists or far-left. In 2005, it was 85%. And today, maybe it’s 100%. This doesn’t happen with scientists. Scientists are, in a way, like society in general. Fifty percent said they were center-right, and fifty percent center-left. The left completely dominates the Humanities and Social Sciences.

And that’s the issue. Of course, thinking about the effects of colonialism is very important, as is thinking about the environment or racism. But the question is: how can you create art that addresses these topics and is also good? That’s not so easy. If you look at the 20th century, there are many examples of famous artists who dealt with social or ideological themes and created perfect art. Picasso’s Guernica is a great example. But the piece itself is only part of the story. People say that the German Expressionists made art about the horror of war. Still, the form, expression, and ability to communicate through colors, shapes, and composition were as important as the theme.

Has it always been this way?

Western European art dealt with ideological themes or certain ideals, such as Christianity. In the 15th century, artists didn’t create abstract paintings; by depicting sins from the Bible, they contributed to educating people or conveying a moral message. However, they made paintings, not text, offering something unique. Today, you can see these paintings and sculptures, and even if you don’t care or know anything about the subject, you can simply enjoy them as art.

The problem with the contemporary shift towards social or political art, which intensified about five or six years ago, isn’t that it’s inherently wrong: I don’t see much art addressing these topics and being excellent. The last time I participated as a panelist in an art biennial conversation in Korea, I saw around eight award-winning works; maybe only one had some artistic value. The rest were very unprofessional, and, if you compare these works to the level of students in the best art schools today, these people wouldn’t be accepted. Many of these works are simply illustrations or confirmations of specific texts written by curators about migrants, colonialism, and this. They don’t add anything to our knowledge about the topics.

It’s also about what’s happening with the left. And when I say the left, I return to Marx, thinking that life must be seen as a struggle. Life isn’t about love, salvation, or building something together: life is a class struggle. Now this message has shifted a bit. It’s about men oppressing women, Europeans oppressing people in the colonies, or humans oppressing nature. Viewing everything as a struggle is an interesting perspective, but it’s a limited one: it’s all you’ll see. There’s nothing more beyond that.

And the other problem with this left tradition is that it’s a highly ideologized system where you have to believe in our idea. And if you don’t believe in our concept, you’re an enemy. In 1917, three days after the Revolution, Lenin closed all newspapers except his own. He wasn’t interested in dialogue. He just wanted to suppress. I don’t quite know why it works this way, but today, when I go to biennials or when I see very academic conference programs, I feel the same kind of intolerance. Very often, when I’ve given lectures in the United States, people would say, “Lev, you’re a formalist!” “What do you mean?” I’d ask. “Well, you’re interested in images, not just written content.” And, of course, I’m interested. Art has existed for 200,000 years, from cave paintings: before language, before ideology, because things like decoration and beauty are essential to human existence. Not everything can be reduced to ideology.

“To be successful, contemporary art needs to open itself to broader themes and be freer to experiment. In the 20th century, artists weren’t afraid to insult people. The artist was someone who mocked society. The artist is afraid to offend because we take school-age children to museums. So, art has become very obedient, safe, and as a result, boring.”

What’s the alternative to this highly ideologized discourse? In fact, what’s the alternative to contemporary art?

Until the 19th century, artists were craftsmen. They were ordered to paint this or that but still created incredible art. The idea of creativity or expressing individuality didn’t exist; it was an invention of the Romantic period. And then we have modern art, from Impressionism to the 1970s, where people explored all kinds of things.

But much of this art is about abstraction, deconstruction, etc. It’s no longer about the human face or human emotions. So, what happened to traditional art? Mass media picked up the themes it addressed. So today, true art, in a conventional sense, isn’t in museums. Museums have something else. True art is Netflix, incredible Korean dramas, movies, popular novels, and songs. Mass culture addresses themes that contemporary art has abandoned, like revenge, love, and jealousy: it basically shows human life as it is but in an artistic way.

When you go to a museum, what you see is something else. It’s like “Art 2”. But in reality, it has no connection with traditional art, which is fine. Still, of course, it’s limiting because it means that people from Hollywood or Netflix are the only people dealing with representing contemporary life or emotions. At the same time, artists have abandoned their traditional roles. So, for me, the most exciting art today isn’t art but things like food design, experimental restaurants, or architecture – in other words, what used to be called applied art.

To be successful, contemporary art must open itself to a broader range of topics and be more free to experiment. In the 20th century, artists weren’t afraid to insult people. The artist was someone who mocked society. The artist is afraid to offend because we take school-age children to museums. So, art has become very obedient, safe, and as a result, boring.

I’m interested in hearing your opinion on photography. What reflections on this discipline have you developed after working with tools of cultural analytics or with AI?

The photographic image is the most popular type of image nowadays. In the sciences, people use 3D images, X-rays, and telescopes, but what most people want to see are human beings, right? So we use Instagram. But let’s note that photography isn’t a medium or a collection of media. The only thing that all forms of photography seem to share is that there’s a lens producing a perspective image, but even this isn’t universal. In the 1920s, artists like Man Ray began making photographs without a camera, placing objects directly on photographic paper’s surface and exposing them to light.

This kind of experimentation also happened in cinema. But if you look at a drawing or a painting, they haven’t really changed in 500 years. Now, the variety of photographic processes available was somewhat overshadowed by the invention in 1887 of a Kodak camera for mass use with the slogan: “You press the button, we do the rest.” Essentially, it’s a simplification of the experience. I bought my first digital camera in 2000, 23 years ago: the device comes with a digital sensor, but everything else remains the same: you have a lens, exposure, and the controls are the same. So, the language continues from traditional photography.

But then computational photography appears: various algorithms process the image captured by a phone or a camera. For instance, if you take a photo with a Google Pixel phone today, the captured image goes through 33 different algorithms. Certain phones don’t just capture one image. They’re continuously recording and capturing images before and after you press the button. This way, you can combine the best parts of different images. In other words, photography nowadays is entirely computational and algorithmic. Nowadays, only professional photographers using expensive cameras and adjusting everything manually are doing “normal” photography. Everyone else is doing computational photography.

And now, we have a new stage, which is AI photography. Meaning a new form of photography without a lens. AI can simulate the appearance of the three-dimensional world quite well. But, of course, it tends to be stereotypical, as I mentioned. However, it can simulate photographic artifacts: you can get images that look like they were taken in the 1960s, in black and white, with a particular type of grain, etc. What’s interesting to me is how these new possibilities of AI will be incorporated into the photography done by billions of people.

For example, today, you take a photo, and then you can use Midjourney to add or change something. You can say: here I want a lake. It’s just a matter of time until the software on your phone can do the same. It will be exciting to see that. But we should also be prepared to see a flood of trivial images. I’m scared to imagine it already because when you take a photograph of reality, it’s something more unique. Not everything you see is perfect; clouds aren’t perfect. Whereas AI only makes perfect skies.

That being said, do you consider that we are on the brink of a revolution in popular photography?

Popular photography is on its way to becoming something different: something between photography and painting. That isn’t entirely new, as in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, it was common for people to paint on photographs: that was a way to retouch or colorize these images. AI has made the idea of photography as a documentary medium even less relevant. But this isn’t new either because when Photoshop appeared 30 years ago, it already offered the possibility to make photography something akin to painting. But now, of course, you can do it much faster.

The last thing I want to emphasize is that photographers nowadays are often asked to make videos, given the popularity of YouTube or Instagram reels. However, as popular as videos are, they are not replacing still images firstly because it takes more time to watch a video. Secondly, if you want to communicate a message and make an impression, the still image remains the best choice because you can control everything. So, I believe we will continue to live in this era of photography. AI or a camera could make it; it doesn’t matter. Photographic images — realistic and detailed images in perspective — will continue to reign for decades.

And then, what will happen in 2050? It’s a fascinating question. I don’t know. Perhaps we will have portraits containing all your data: everyone you’ve met, ideas, and DNA. Something like data representations. We’ll have to see.