Reflections and potentials: the photography of the black Amazon

“Finding an Amazon the color of my skin, different from what I imagined, gave me access to places I never thought would exist.” In February 2010, Marcela Bonfim arrived in Porto Velho, the capital of the state of Rondônia in Brazil. She came from São Paulo and had graduated two years earlier as an economist, and in her search for a job, she ended up in the Brazilian Amazon. It took her almost a year to understand her arrival in that city. Hydroelectric plants were under construction, some in high production, and the town was full of foreigners. She was just one more.

She began to get to know the city, make it her own, and many people identified her as Barbadian. The inhabitants of Porto Velho are descendants of migrants of African descent from Barbados. They arrived at the beginning of the 20th century to work on constructing the Madeira-Marmoré railroad. They were not the only ones. People from more than 20 countries came. However, that was the largest migration.

Marcela met and saw herself reflected in many of these people and decided to travel the rivers and the black Amazon. Thus, she also found the relationship of those roads with the roads of the wood.

Why did people identify you as a Barbadian?

When I would go out, people in town would sometimes ask me if I was a Johnson or a Maloney, and I would ask, “What is that?” I asked my comadre, and she explained that they were the traditional black families of Porto Velho. She told me part of the story, and then the city told me the rest, especially when I met Bubu Johnson playing a samba. Soon I was already in the Johnson family’s backyard playing with them, living a story that I didn’t know could exist.

People imagine Amazon as an indigenous place. This regionalization simplifies the reality of indigenous peoples and hides what happens in sites like the Amazon. It is like when people talk about Africa as a country. Not as what it is: a continent with so many cultures.

Rondónia’s image brought me these elucidations because photography does not happen at the click moment but before taking the picture. Everyone knows what they want; they see the image they will make. The photo is an image that, in a way, already exists. I think that we photographers don’t create anything. We already have the images. I am here to create reflections and potentialities.

You were an economist and went to Rondônia to work as such. When did you start taking photographs?

I started the moment I met the Barbadians. I went to meet them in their backyard. At that time, I was working in the government. I had achieved a position, and I already felt that pressure because of my skin color at work. No matter how hard I tried, it was impossible to please. My grandmother had talked to me a lot about that; she said that I would never be liked at all, that it was better not to rationalize that too much. So Johnson’s yard was a relief.

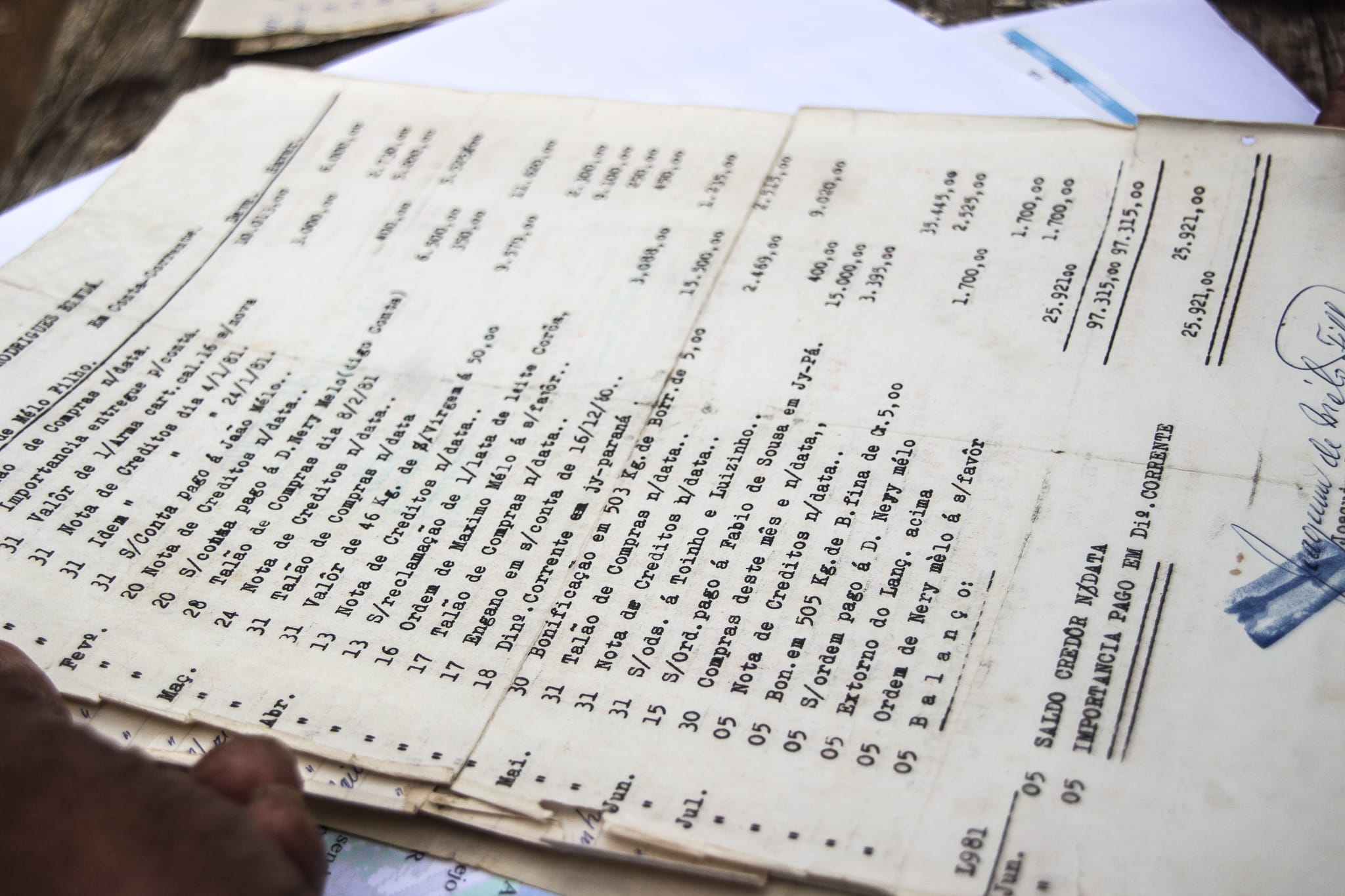

I decided to buy a camera to show the pictures to my family. I wanted them to see how beautiful everything was there. The camera became a travel pass. It took me to places I never imagined inside the image, to the stories. And to the features, all that became an aspect of strength, I learned and met other blacks at Johnson’s house, other people of the Caribbean and English Guyanese descent.

Then, I began to question the Brazilian social imaginary, which is colonial, does not like black culture, and does not like multiplicity. I learned a lot. I thought that the black was the only one, and no. Many nations are within this funnel of what it means to be black today.

The reflections are a way of thinking about those black bodies today in the diaspora, knowing that we are still searching for our places. I fit very well in Rondônia from those reflections that made me put my image in a vital plane. Photography, for me, can be critical or lethal. For me, it is to bring a political and humanitarian issue. Because the racial problem already exists and was not created by me. That is the most significant reflection. I am a racialized figure. The information of who I am is already in many people’s heads. That image already exists. Before I get to places and present myself, my print arrives before introducing myself, and I depend greatly on what others think. And this has to do with a robust economic issue because capital is established on skin color.

And how do the potentialities that you create from these reflections work?

It is what we don’t know: the inner side of the image. The image has life. It has a history. It is not that plastic that has endured throughout history that people are passionate about and poeticize poverty, racism, and even violence.

The power of the image is what it has not yet worked on. It is the internal aspects. To create that racial reflection and cutout within the plane of photography is essential today to think, at least, is a significant humanization of the black and the indigenous.