Reverberation and subtlety: possible relationships between photography and memory

Brazilian photographer André Penteado came to photography in an intuitive way. When he went to a friend’s house for a party, he carried an Olympus with a fixed lens and film to record what happened. At the age of 18 he took his first photography course, between the ages of 28 and 40 he did commercial photography and from the age of 40 he decided to become a visual artist, a creator.

He shares with Jeff Wall, one of his great references, a love for the ability of photography to record the surface of the world. Although, unlike Jeff, André does direct photography.

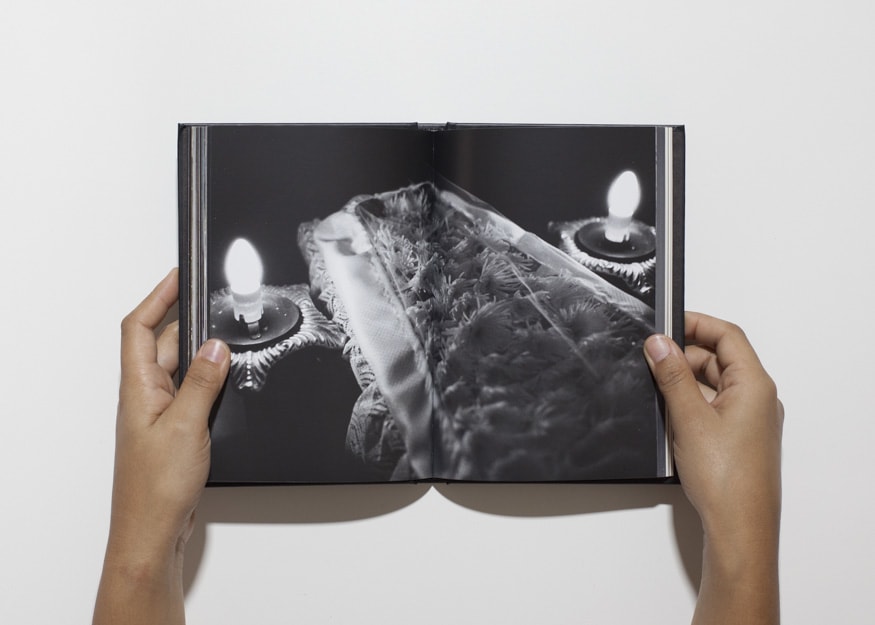

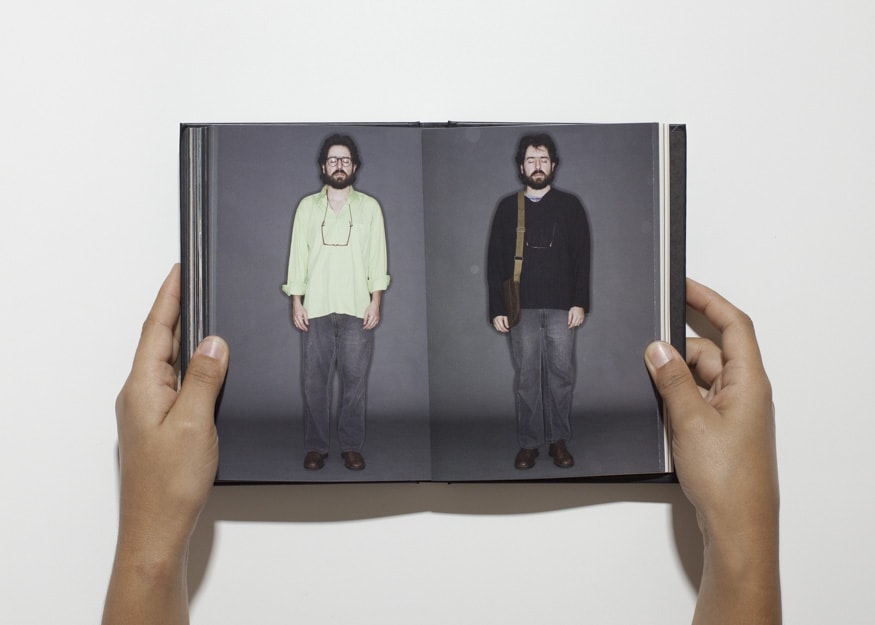

Dad’s Suicide – André Penteado

André has made several photobooks. One of his study group posts quotes Gerry Bagder: “Photography is, in essence, a literary art, in which photos arranged in a specific sequence can say more than the mere sum of their isolated parts. ”. That is, perhaps, one of his flags.

For him, “photography is the most melodramatic of all the arts.” Sometimes, he considers, you have to allow yourself to go through that melancholy (as in Dad’s Suicide, a production based on the mourning for his father’s death) and at other times, avoid it, as when it comes to political events. He is currently working on five books on brazilian historical events.

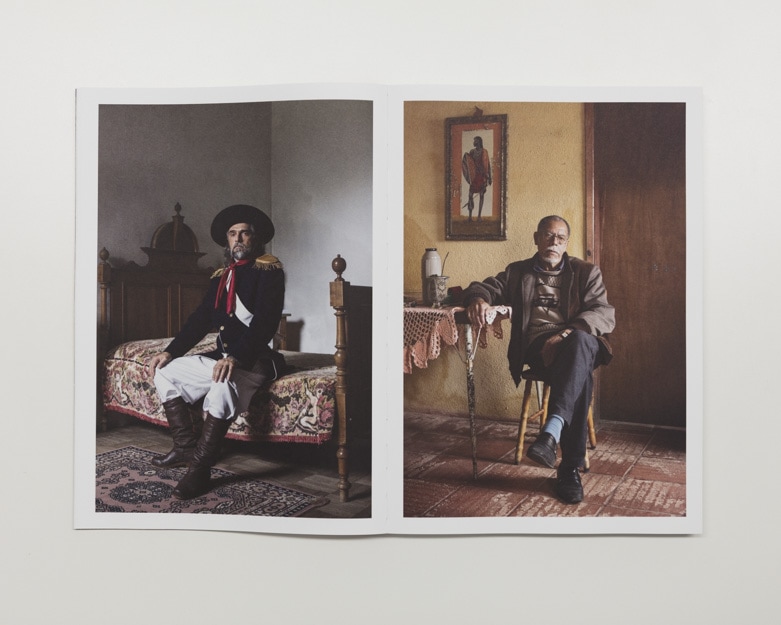

So far he has published three books: Cabanagem (2015), French Mission (2017) and Farroupilha (2020). The first and the last are contemporary and André contrasts them: one is a popular revolt that nobody knows about and the other is an elite revolution of which there are books and series. Why?

Dad’s suicide- André Penteado

Many people say that you do work on memory, both personal and collective. What do you think of that way of classifying your work?

I think it does have to do with memory and the construction of historical narratives. A few days ago I read that what we can see in our heads is what it is possible to decode from such a complex reality so that we can navigate life.

I really like the idea that photography is a cutout, that it freezes a moment and allows us to look at a very complex scene with much more attention. Photography captures the surface of reality, not the inner world. It is always a reading that the photographer makes of the surface but allows us to be in that moment.

We all build a narrative: if we both see the same moment, we are not going to tell the same story. I am going to interpret it from my reading and you from yours, that doesn’t mean that that moment has not happened. Memory has a lot to do with that, it captures what happened and saves it. I have a large photo archive, I have pressed the button on my camera at least 650,000 times. I wonder a lot why I did that.

Farroupilha – André Penteado

At first I took pictures just for myself: I went to a party at a friend’s house and I carry 10 rolls. In part, photography has a strong tendency to melancholy. Part of my job deals with it; the other side tries to avoid it, especially in work related to political and historical issues.

In my personal works like the suicide of my father, there is a reverberation of memory and melancholy. In political works (those on the history of Brazil such as Cabanagem, French Mission or Farroupilha) I want to understand how that memory of an event that happened a long time ago continues to reverberate in the present even if we do not understand it.

In history books we read that the Cabanagem happened. Between 1835 and 1840 there was a revolt, it ended, they were defeated and then another historical event happened. I constantly think about this: life is an infinite branch of events. I understand, from my reading of historians, that one fact branches out into another fact, into another fact …

Each life is infinitely touched by that event. This generates a complexity of relationships that reverberates to this day, like a stone or a drop of water that falls into a lake and creates waves, creates waves, creates waves, which then become more and more subtle but continue.

Farroupilha – André Penteado

In that sense, do you think that memory is a construction or a reconstruction?

It is a very interesting topic and it was a debate I had with Jocelito Zalla, the historian that I invited to write the text in Farroupilha. For me life is a construction. I think about what is discussed in the therapeutic process of psychoanalysis. There was an event, which actually happened, but how do you interpret that event? What impact does it have on your life?

The photography that I take is not a constructed photograph. I go to places and photograph what I find. Only, even so, I am aware of all the decisions that as a photographer I have to make to create that image. It is still a construction from my ideological point of view. Historiography, for me, is the same.

All the time we are building narratives to survive the complexity of the world. I perceive a political truth of what I think the world is. But I also understand that each person has theirs. It is a constant process of construction and reconstruction. Life is formed more by voids than by certainties and, therefore, I am always building a narrative in my head and you another. History and memory are constructions and reconstructions.

Farroupilha – André Penteado

En Ante el dolor de los demás, Susan Sontag dice que, en un sentido estricto, no existe lo que llamamos “memoria colectiva”. Para ella, la memoria es individual y la colectiva es una declaración.

Creo que voy a escoger el camino del medio: son los dos al mismo tiempo. Es decir, las personas viven hechos, acontecimientos y cargamos memorias anteriores a nuestra existencia, que reverberan mucho más allá de lo que podemos entender. Cada individuo carga la memoria de su familia, de su historia, de cómo fue criado, una cantidad de cosas inconscientes. Al mismo tiempo, para sobrevivir socialmente necesitamos alinearnos con ciertas narrativas y memorias colectivas. De lo contrario, nos quedamos muy solos.

Nuestra necesidad de dar sentido a la existencia y a lo que acontece en nuestra vida hace que nos identifiquemos con discursos mayores. Si no, no existiría la religión, las ideologías o las barras bravas de fútbol.

Farroupilha – André Penteado

There the relationship with history appears. It’s very curious that people recognize history when big things happen, like protests or a pandemic. It is a way of thinking of history as a series of specific events, but what happens when we think of it as a series of narratives?

History is a constant. Right now we are making history. One of the things that I found when I started the work on Brazil was the concept of microhistory, which is the understanding from small events.

Much of the events of our life do not enter the books. It is very interesting to reflect on that idea of episodic life. If I talk about my life, I will mark it like this: I was born in São Paulo, I moved to Bahia, I returned to São Paulo. We always talk about the big frames.

We need to make that big story but also think about the small one. The transformation that society needs is great. It is not enough to stay meditating and think that this is how everything is going to transform, but at the same time I need to meditate in order to live. If not, I can’t breathe.

I remember the sadness I felt at some moments in my life, the rejection of direct elections in the 80s, the sadness over Lula’s defeat in 1989, the euphoria with Collor’s impeachment or with Lula’s first victory, the sadness with some commitments that Lula assumed after his victory, with Dilma’s economic policy or impeachment that had no reason to be. Those are the big events, but at the same time other things are happening. My books try to address those little facts. The great ones are already in history books.

How was the process of producing the books?

Before starting these projects I was reflecting a lot on the relationship between history and photography. I was thinking of a possible parallel: the two start from reality, the two try to read and construct a narrative. Both the photographer and the historian make an interpretation based on their ideology. The framing is a decision, the editing too. Which of the 40 photos I took of a scene will I choose? What would be the truth of that scene? It’s my truth but that scene happened.

The historian analyzes documents, interviews people and builds a narrative that is true of that event. Some of these narratives touch me more and I think that some are closer to my world vision.

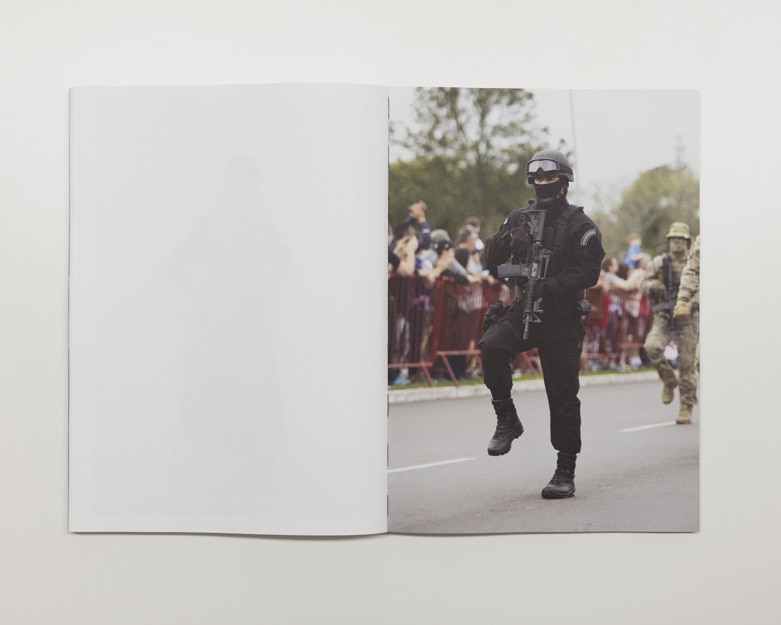

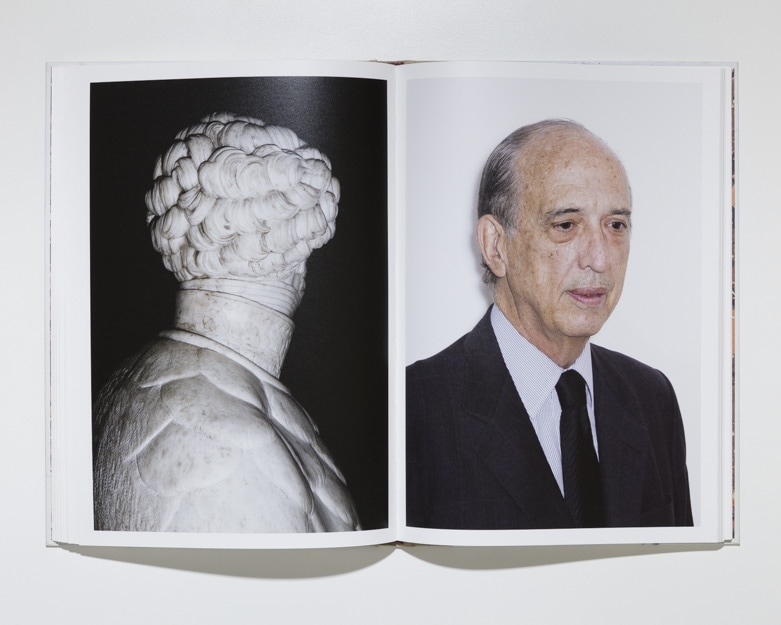

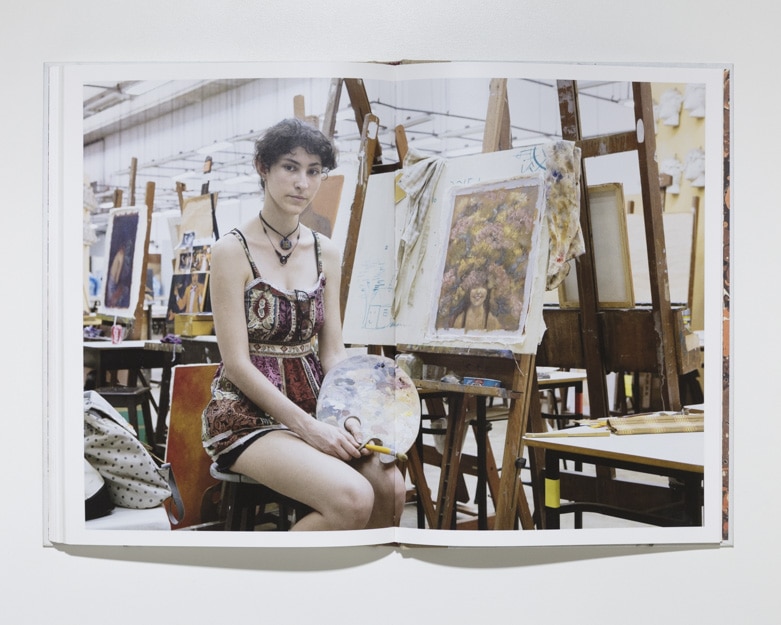

French Mission – André Penteado

But why do people generally believe that the photo and that historical narrative are “the truth”? What is the book that students are given as a narrative? I grew up in the dictatorship and I know what book I read. I studied in a nun’s college and I see that choice as ideological. But mine is also, so what are my ethics? What are my decisions? What do I leave open?

My work process is very analytical. There is always a procedure, which can be to dress myself in all of my dad’s clothes after his death and take pictures of me on a gray background. There is an intention to give an account of reality through a procedure that passes through a rationality, but with this I hope to achieve an irrationality, a feeling. In my work I try to make photography “colder” just so that the image does not fall into something hyper emotional or dramatic. Photography is, in a sense, the most melodramatic of the arts and it is very easy to stay in that layer of drama, which is the photo on the front page of the newspaper. We need to look at things differently.

I lived for seven years in London. When I was thinking about that relationship, I returned to Brazil, in 2012. The following year there were great manifestations. Brazil has a discourse created as a country “of joy.” But any observation of reality, such as seeing the police entering a community and killing 30 people in a single day, shows that since the colony this is an extremely violent country with who have no possessions.

So I decided to study the moment when the Brazilians decided to rebel and I found a list much larger than what I remembered studying at school. In that search I came to the Cabanagem. I was shocked: it was a popular revolt in which it is estimated that there were more than 30,000 dead, approximately one third of the Amazonian population at that time. They also killed the governor of the province. In other countries with victorious revolutions there are heroes, not here: they were erased.

French Mission – André Penteado

As I continued my research, I discovered that this happened before the invention of photography or its arrival. I found it very interesting to photographically investigate an event that had no photographs. So I decided to do a project that includes five books, so far I have done three. I started with the Cabanagem, and I also worked the Farroupilha because they are contemporary. The first is a popular revolt that nobody knows about, its leaders have been erased and the second is an elite revolution that everyone knows about, of which there are books, television series. There is a whole imaginary about it and its heroes are exalted.

In my methodology, the first thing I do is read many books by historians about these historical events. As I read, I create a list of possible photographs. Thus: the governor of the state of Grão Pará was assassinated on the stairs of the Government Palace, that palace became the Historical Museum of Pará. On my list, it appears: “photograph the building of the Historical Museum of Pará”, “photograph the staircase”. Which ladder? There are several and they do not say in which one it happened. I do not care about that.

When I went to the Museum, I began to ask myself some questions during the creative process of this project: How can I relate to photography an event that happened 180 years ago or a little less, and that has no photography, and that reverberates to this day in ways that I don’t understand? I drew a spiral with many layers, each one of them was: facts and places where things happened, contemporary places that are related to the event, contemporary people who are descendants of the Cabanos, historians who study the Cabanagem, the archive where documents of that time are kept. There, I simply go to the place and take pictures of what is there: a portrait of a descendant, the museum guard, the museum director, the staircase… I look for that emanation of the event in the present.

French Mission – André Penteado

After doing that -I have done it for all three books- I return to the studio and dedicate myself to looking at the photos for a long time, until I understand the story they tell me. They are almost a travel journal. I was in Pará for three months and took thirteen thousand photos.

I tried to edit them as a flow photography book but couldn’t. It was Iatã Cannabrava who told me, upon seeing the material, that I had taken only 6 photos in that work: the dilapidated nature, the violence, the bureaucracy, the humidity of the Amazon that breaks things, doors and passageways and portraits. I understood why I couldn’t edit it, but I also knew what the true concept of the book was. It is not that nobody knows the history, it is that the history of exploitation and violence in the Amazon repeats and repeats itself. The violence and religiosity that existed in the Amazon in 1835, still exists. So I ended up doing a cyclical edition, without explaining much there is always a door that repeats itself.

Fotolibro Cabanagem – André Penteado

What I propose in these books is not an understanding of the historical event, it is to try to generate a feeling in the reader that it continues to reverberate to this day, even if he does not know it. The feeling I want to generate is the same as when you go to sleep or when you are waking up. There is one thing there that one is going to capture and suddenly it goes out. The dream that is forgotten right after waking up, or the thought that is diluted in the dream. Something that is almost understood but not entirely, that is my intention.

French Mission – André Penteado

Cabanagem is like a cyclical travel notebook and it doesn’t get anywhere because it keeps happening over and over again. In French Mission I have a first part that is the chaos of the present, everything that the artists of the French mission dreamed of teaching before arriving in Rio and finding all that confusion. Then comes a text that is the letter from the creator of the Mission, with his proposal for the school. That is the perfect dream, the plan, which in Brazil was never executed. Brazil plans and does half. And finally there are the artists, the dream that remains.

In Farroupilha, what for me began as a glorified story, ended in a mosaic of relationships with power: where it is exercised, who struggles to find a plot of power, when it becomes a play told and recounted with the narrative of the victories, the monuments, the violence of war, the violence as a metaphor on meat in a steak.