Soy is not a recent crop in Argentina. According to Guillermo Cadenazzi, there are records of crops in the early twentieth century, by the middle of the century there were less than 1000 hectares cultivated. Already in the 1980s it was one of the main crops, with approximately 2.040.000 hectares and by 2008 the area sown exceeded 16 million hectares, that is, 50% of the cultivated area of the country and the only crop in many provinces. Starting in 1996, in Argentina not only soybean cultivation increased, but also the use of agrochemicals such as glyphosate, the active substance of the herbicides most used in transgenic crops.

The photographer Pablo Piovano began to hear in 2014 about the effects that the use of agrotoxines such as glyphosate had on people. After talking to some colleagues, he decided to go on a trip. The first house he visited was that of Fabián Tomasi, who was already one of the most critical activists of the use of agrotoxines such as glyphosate and who died in 2018 from diseases caused by his contact with agrochemicals.

Pablo found out little by little. In 1996, the Argentine state approved in a process that was too fast and, according to some journalists, amid some irregularities, the use of glyphosate-resistant transgenic soybeans. 80% of the texts in the file are in English and despite requests for reports on possible health effects and it use in other countries, the state approved the use of the seeds.

Since 1996, “Argentina turned into a testing territory. 370 million liters of agrochemicals. 22 millions hectares have already been sown with transgenic seeds, this represents 60% of the country’s arable landmass. In some towns on less than a decade pediatric cancer cases have been tripled. Early abortions and unexplained birth defects has also dramatically increased to 400%. A preliminary collection of data on the sprayed villages with glyphosate says that 13,4 millions of people are afected.”

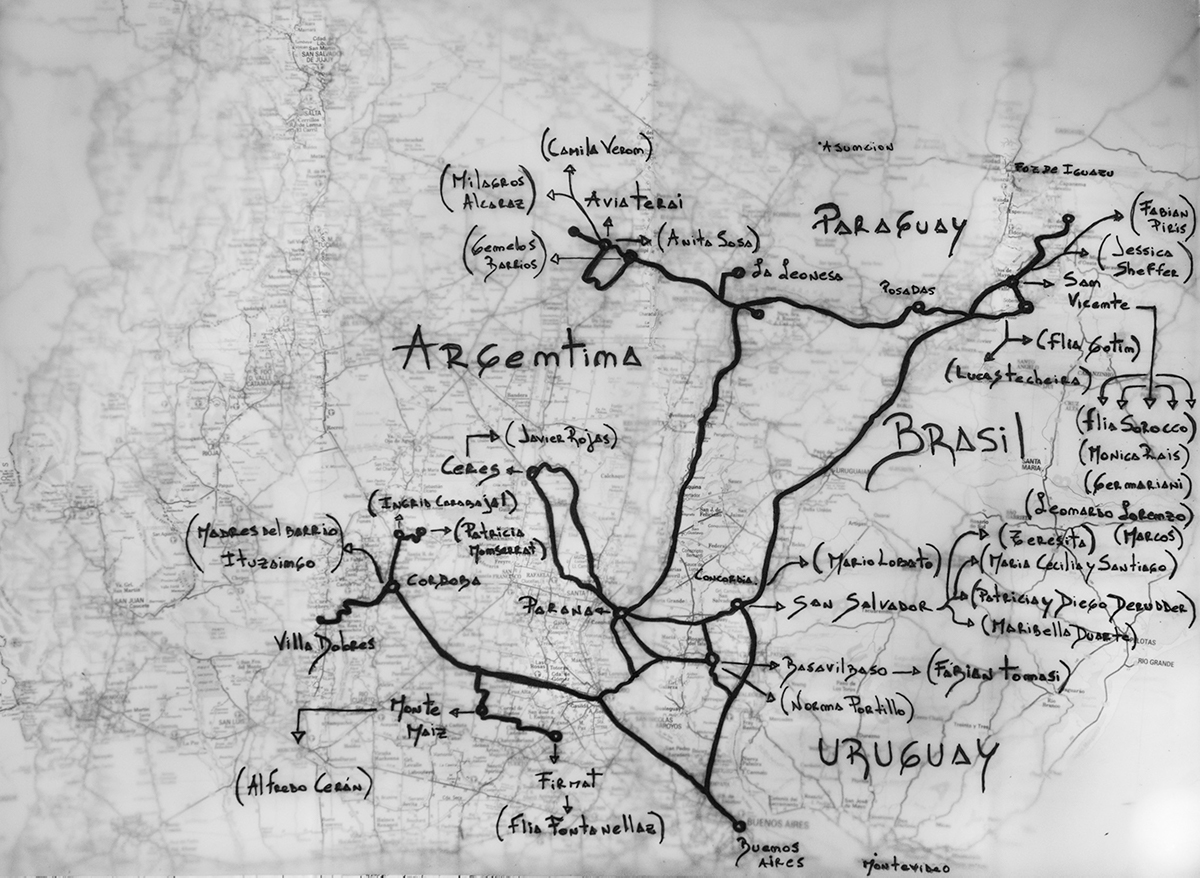

The former quote is part of a short documentary that Pablo made. On that first trip, he spent 4 days at Fabián Tomasi’s home, who helped him build a route that he has followed ever since. In 2017 he published the book The Human Cost of Agrotoxines which documents the consequences and impact of the use of these substances on human beings for the last 20 years in Argentina. To do so, he toured the provinces of Chaco, Entre Ríos and Misiones. He visited families, towns, organizations, made friends and supported processes.

How did you get to this topic and how did you start The Human Cost of Agrotoxines?

It was in 2014. At that time there was little information. That was the engine that made me go out to visit a good part of the northern rural population. In 2014 you searched “pesticides Argentina” on Google and in an hour you had nothing more to read. Now you can be reading for months, that is, somehow I think that the different disciplines have generated a popular conscience, they have set the issue on the table.

I had seen this information coming through some alternative means and I decided to take my car, my camera, I asked for a vacation and I left for a month. The first step I took from Buenos Aires was to Entre Ríos, 400 kilometers away, to Fabián Tomasi’s house. Seeing Fabian was a summary of everything that was to come. The word of him inside his body was so powerful that he moved me. I spent four nights at his house, talking a lot. He helped me to weave a kind of map to continue the work that was very fluid, because it was as if they were waiting for me on each side.

In each house that I arrived, they gave me the best chair and there was an almost total disposition to talk and to take photos. In addition, it was a very sensitive issue because it was always traversed by pain, by children who cannot dance, by children who cannot run, by children who have congenital malformations, especially spina bifida.

In these houses bordering the fields it used to happen that children are born with malformations and that is because when women are in the first three weeks of pregnancy, the risk of contracting a malformation, if they are in contact with some powerful chemical, it is multiplied by seven.

How did they come to make the correlation between what was happening in their bodies and the pesticide?

They began to realize that when there was a fumigation they ended up in the waiting room of the town hospital. The children had a skin breakout or some respiratory problems. That was almost immediate and in some cases it was more serious: hospitalization or direct death from just being in contact with a fumigation. Then it was born, and it was what alerted me and mobilized me, the Red de Médicos de Pueblos Fumigados. They were several doctors stationed in different towns who were seeing that children with skin problems came to these hospitals, with respiratory problems in the fumigated towns.

At the University of Rosario, Damián Verzeñassi responded quickly to that, he is a doctor who in the last subject of medicine took his students to do a thesis in the fumigated towns and they did a house-by-house sanitary survey, looking for diseases. That was also very useful to establish causality and to support what was only a murmur, because it is very difficult to determine.It is almost impossible to directly relate any health problem to the fumigations, it would be necessary to study the body before it has something, if not, you cannot say this child was born malformed by that fumigation.

¿Cómo son los paisajes que van desde Buenos Aires hacia estas provincias, y de los pequeños pueblos colindantes con los monocultivos?

Argentina is a country that has very large expanses of land. Agriculture has historically sustained the country. In the 1940s, when the world was at war, Argentina sold corn to everyone. It has always been an agricultural, livestock country; but with a certain diversity. Now, what is happening, especially after 1996, is that the productive matrix of the country has changed, because monocultures are gettin stronger. Then diversity begins to break down and we only have soybeans and corn. Almost all transgenic.

In 20 years, the change was very resounding since the use of transgenic soybeans in 1996, thanks to a law that was introduced almost secretly, with pages in English approved by the Monsanto corporation, without being contrasted by Argentine scientists , neither from the State, nor independent studies. It is approved in three months behind the backs of the people and there all this begins to move in a forceful way.

At this moment half a million liters of agrochemicals are used per year, if we divide it by the population, it gives more than 8 liters of chemical per person. It is the highest chemical utilization rate in the world.

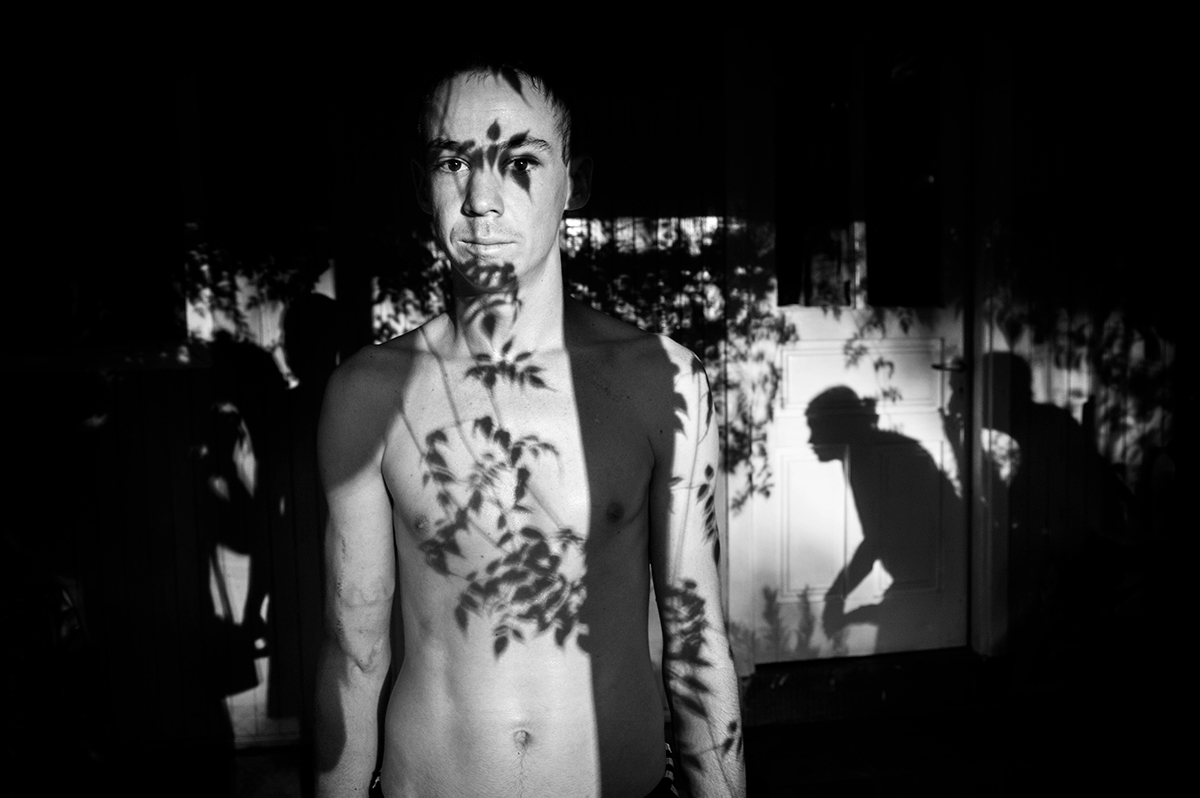

You mentioned the complexity of this work, in the sense that you were going to photograph people who were in deep pain, how to portray this with dignity?

It’s tricky because it’s so easy to fall for a low blow when it comes to malformations. Simply, I believe that it is to generate that thread, that fabric between what you see and what you are so that it is made with dignity. Although the pain of the other is not our pain, there is a fiber that moves, it touches us all and if you are close you can see it. Despite the pain, all the work is traversed by the love of the mother. This work, in its core, is a prayer to Mother Earth. And I speak of the mother because it is they who finally give life to those children who are prostrate or who have a disease.

What I did was take the time for the portrait to be solved in a dignified way. Many times I would return, sometimes I would spend whole days in a single house. Sometimes I went back and forth, I did another 500 kilometers again because I saw that the result was not enough. I looked at childrend as if I were the father. For that photo to be publishable or to be part of the body of work, I had to feel it as if it were someone close. And I think I took the time I needed, I have returned many times to many houses and other times I didn’t have to return. Sometimes everything lines up and something else happens and other times you have to think about it.

I think that is accomplished, that dignity is a gesture. Ethics is an aesthetic gesture that has to do with beauty.

Ethics is an aesthetic gesture that has to do with beauty.

It also has to do with closeness and putting on the body, right? And without your body it couldn’t be done either. How did you manage to do this job without ending up feeling bad?

I think it’s handling that finite thread where you go in, but you also have an exit. Because if you can’t get out, you can’t continue, you can’t fulfill the purpose. And the purpose was long, it took me many years. In fact, it still continues. Now I have to go out again on a commission for an NGO, we are investigating Syngenta.

And it is also time. I suppose it will happen to doctors, it will happen to many other trades. When you enter the pain of other it is necessary to have a connection. But it is a fine, delicate connection that has an entrance and an exit. We can be vigilant and respectful. Being responsible for what we are being allowed to see, for what is being opened to us, because what is being opened to us is total intimacy and that has enormous value.

Intimacy for me is a gesture of openness and you have to live up to that gift of wanting to accept you in their space, in their heart. You learn, it seems to me that also with the years of profession, right? To be, but also to know that this is not your reality, that you are a narrator, that you are an intermediary for that to be put in the center and hopefully it will raise some kind of consciousness and awaken something, it will be useful. For me the purpose of work is to be useful, to be useful for something, that is at least what sustains me in my profession.

The first house you visited was Fabian Tomasi’s, how did you get there?

Look, I wasn’t the first to do this job. Getty Reportage had already done similar work. I saw the work of a very good journalist, I interviewed her before going, and I don’t know if she was the one who gave me Fabián’s number. Or an AP photographer who was also at his house. I simply called Fabián and he told me: I’ll wait for you, come whenever you want. And so, very quickly, we hit it off with Fabián, until he died he called me once a week on Skype. We had a very beautiful relationship, for me he became a very inspiring guy, and not only for me, but for a good part of society.

Fabian could hardly move. Finally, he controlled only one finger and with that finger he was able to type and on social networks continue saying what he thought or giving interviews until the last moments to speak up.

People from all over the world came to his house. Artists, journalists, people who were cycling to see him just to get to know him. He received them in a very humble home, but with open doors. Despite being like this, with that physical pain, he made us all laugh, he was the joker of the house. I saw him and I always felt a bit silly because I saw a guy who was completely full of pain and at the same time with a humor that seemed to me a gesture of enormous beauty in life. And at the same time that his body was decreasing in capacities, his consciousness was rising, he was becoming more ethereal, he was going away and his consciousness was increasingly fine and his sharpest word was penetrating each time.

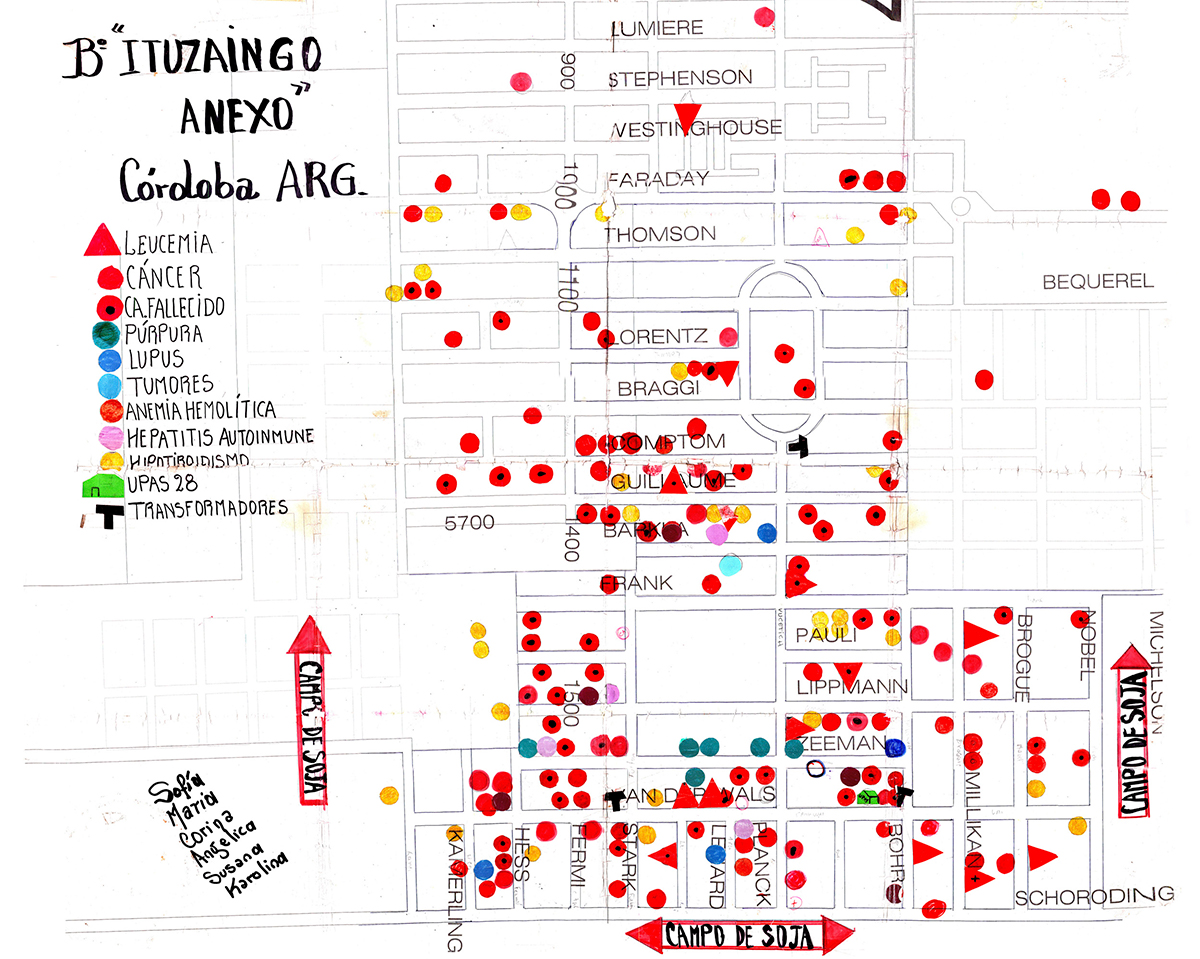

Among the images of your work there is a map of Ituzaingó, where illnesses and deaths are shown house by house. On that map you can also see that there are houses that adjoin the soybean fields.

Of course, that was a survey made by mothers who lost their children. They did it in an artisanal way. They visit house by house. It was the same thing I was telling you about what the University of Rosario did, but in entire towns and with an academic method. But hey, they did it by going from house to house and it has enormous value, because they, being victims, go out to demonstrate what is happening with this map.

At the same time, struggles broke out on different sides. This of the mothers was in Córdoba, about 800 kilometers from here. Those same mothers kicked out Monsanto. Monsanto wanted to build the largest plant in South America and they could not do it because of the resistance that was generated there in Córdoba, and these mothers were protagonists, they won that battle. It was impossible to think that such a large corporation could pull out, and it had to.

Two or three years ago, I was interviewed thousands of times because of this roject, mainly because the journalists who work in the fumigated villages could not speak because they were threatened. So I gave two or three interviews a day, at one point it was unbearable to listen to myself. But it seemed to me that it had to be done, now there are thousands of people who can speak with more integrity than I can, and I hardly give interviews anymore.

In interviews, they asked me, what do we do with all this. And there was no positive answer. Now there is. Before, one said agroecology, let’s go back to farming. But those were words in a vacuum and a silly dream. Today the UTT was born, which is the Unión de los Trabajadores de la Tierra who are producing in a fantastic way, agroecological pockets arrive in the city and they are occupying more and more spaces and territory. We are before the positive answer, before the possible solution.

Finally, what is being shown is that the same is grown. Without agrochemicals, the yield is the same, or sometimes even more. In Santa Fe there are large areas of soy that are grown without pesticides and the yield is the same.

If you think about half a million liters of pesticides, the bill in financial terms is huge. It is big business. It is a gigantic business from the sale of seeds to the use of chemicals, to the agreements they have, which are very spurious agreements with the farmers. It is as if we were 400 years ago where they sent the cocoa workers to give their lives and they ended up owing the owner of the land.

The happy thing here is that there is a possible solution and that it is in motion.

This relates to what you say about feeling useful.

Yes, for me it is fundamental, it is the purpose of each movement I make related to my work. If I wonder why I do what I do, in the end that answer comes. That the work is useful, that it can raise awareness, that it support other disciplines for a transformation.

There the relationship with other disciplines is important.

In this case, yes. This work has no sustenance if it is not linked to medicine, if it is not linked to science. We have a serious problem: what is official is based on the State and corporations. So the role that worthy science plays is very important, which is a science that is necessarily becoming something social, that responds to the situations that are emerging and that are of an urgent nature.

I am very grateful for those spaces of independence, which are few but there and which give a huge struggle, almost alone. They are small fights against giants all the time. But hey, more and more are starting to appear.