The imaginary territory of a migrant artist

The link between Argentinean Alejandro Erbetta and photography was born on a trip to the north of the country. A Canadian friend gave him an old camera, and he began to explore his gaze. He trained in Buenos Aires many years later, then at the National School of Photography in Arles (France). He also obtained a Ph.D. in Aesthetics of the Arts from the University of Paris 8 Saint-Denis.

Sus obras fueron expuestas en Europa, Asia y América Latina, y él siguió viajando pero ya como parte de una práctica de investigación. Repitió el viaje de sus bisabuelos desde Italia hacia Argentina y fue juntando información, archivos y fotografías. Mientras exploraba la memoria familiar “a través del espacio y el tiempo” también entendía su propia identidad migrante. Todo ese trabajo, luego se concentró en un libro: Reprises.

Is memory an axis of your work?

It certainly is. I have always had a great interest in the past as a possibility of the imaginary. During my adolescence, the literature of (Jorge Luis) Borges influenced me, he saw in memory a chance of fictionalizing time. However, at first, my relationship with photography was centered on travel and wandering. The relationship with memory appeared later.

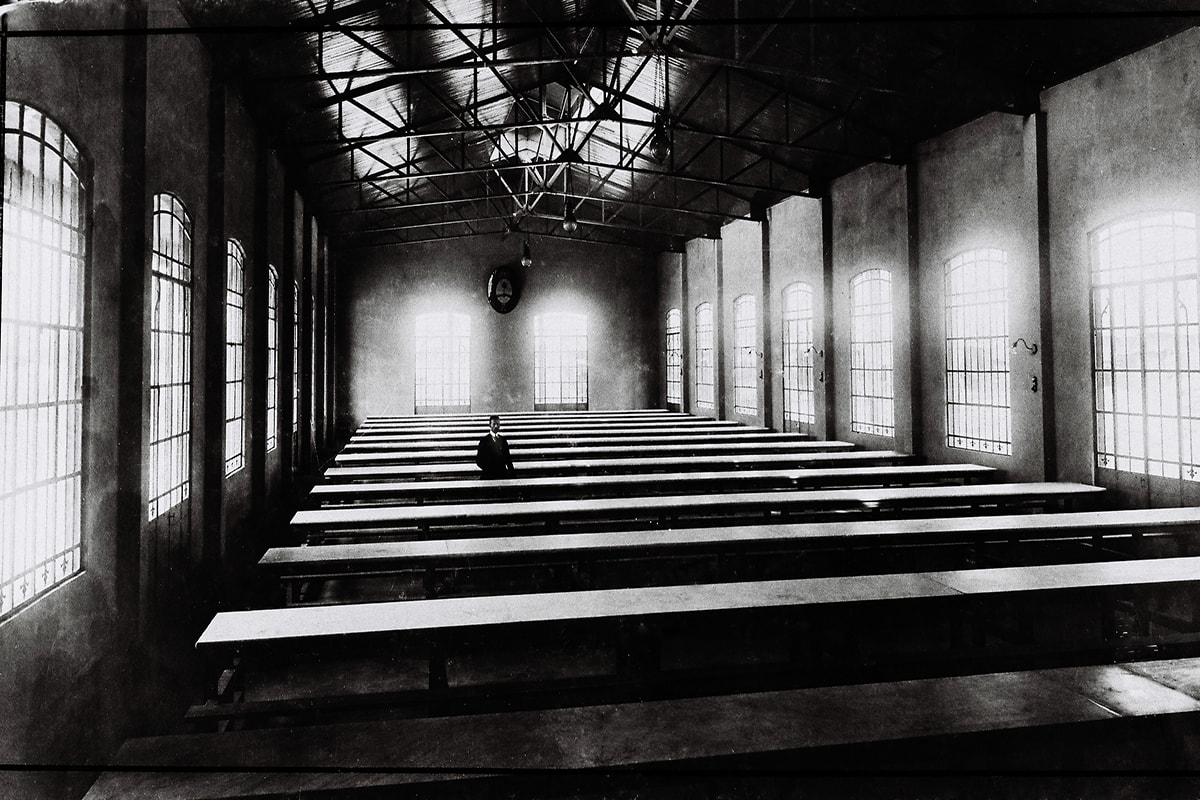

Already in France, after having done my first artistic work, I started to reflect on my family history. I was interested in my ancestors who had traveled to Argentina towards the end of the 19th century and were part of that significant displacement of migrants from Europe to Latin America. In a way, the family history was repeating itself. I would have a similar experience a century later, although my itinerary went the opposite direction. There were departures and returns through space and time, like an echo, a cyclical resonance.

At that time, I began to have regular contact with Italian culture, feel correspondence, and talk to my family. I discovered that we had almost nothing about the family history. There were gaps in the memory, great oblivion. Those blanks and temporary voids became an engine for my research.

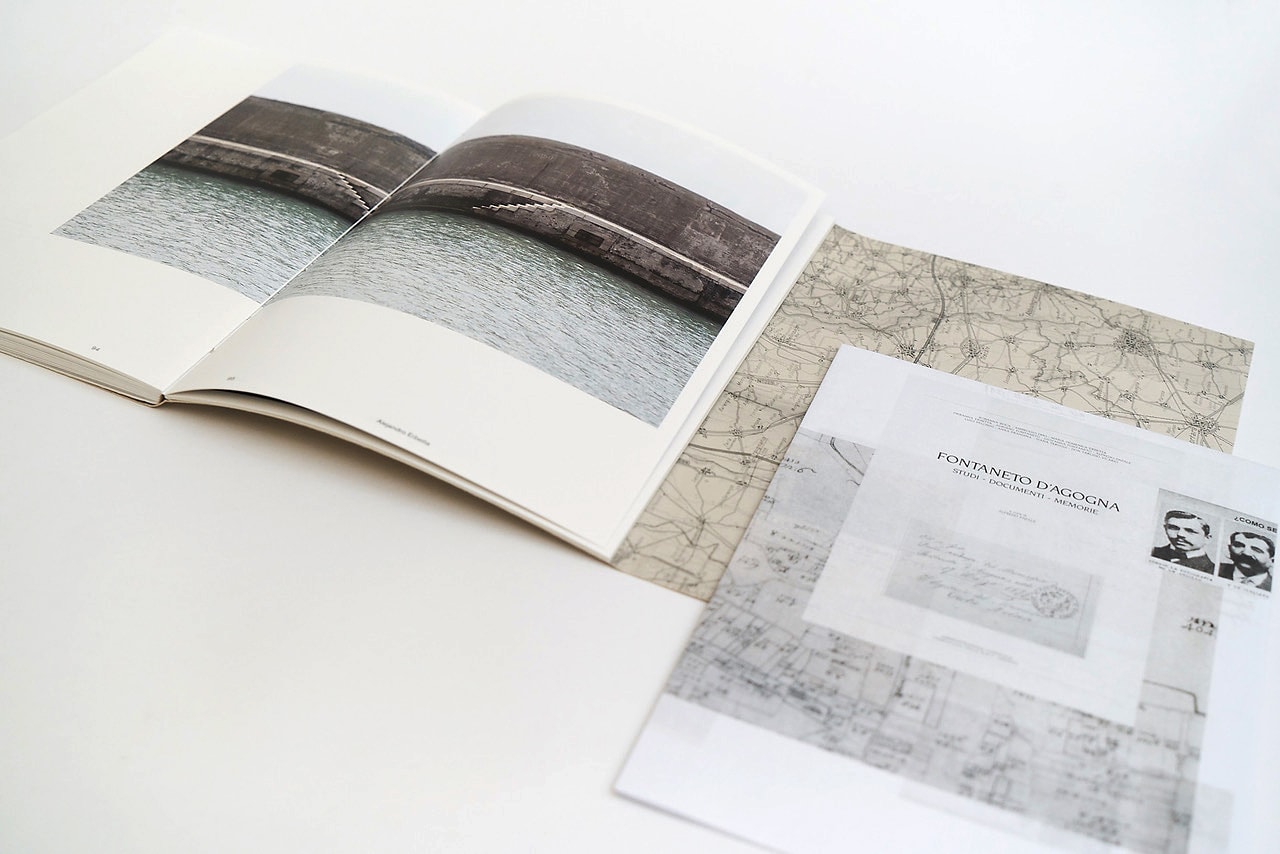

The first idea I had was to articulate the journey toward the family origins with retrospective poetic research. Applying a methodology close to that of a historian, I tried to establish relationships between various documents, texts, archives, and family albums to objectify a story. There was an emphasis on emotion and subjectivity; I was trying to unravel a family enigma, a story lost in time. But how can we reconstruct our history when there are silences, elements we do not know? Is it possible to reconstruct the past and memory through fiction? What would be its legitimacy?

On my first trip to Buenos Aires, I began to compile information about the history of Italian immigration at the time when my ancestors had traveled. At the same time, I started my family research. I found, for example, a person close to the family, a cousin of my father’s, Rolando Castelli, who knew something of the history.

And he was giving you information?

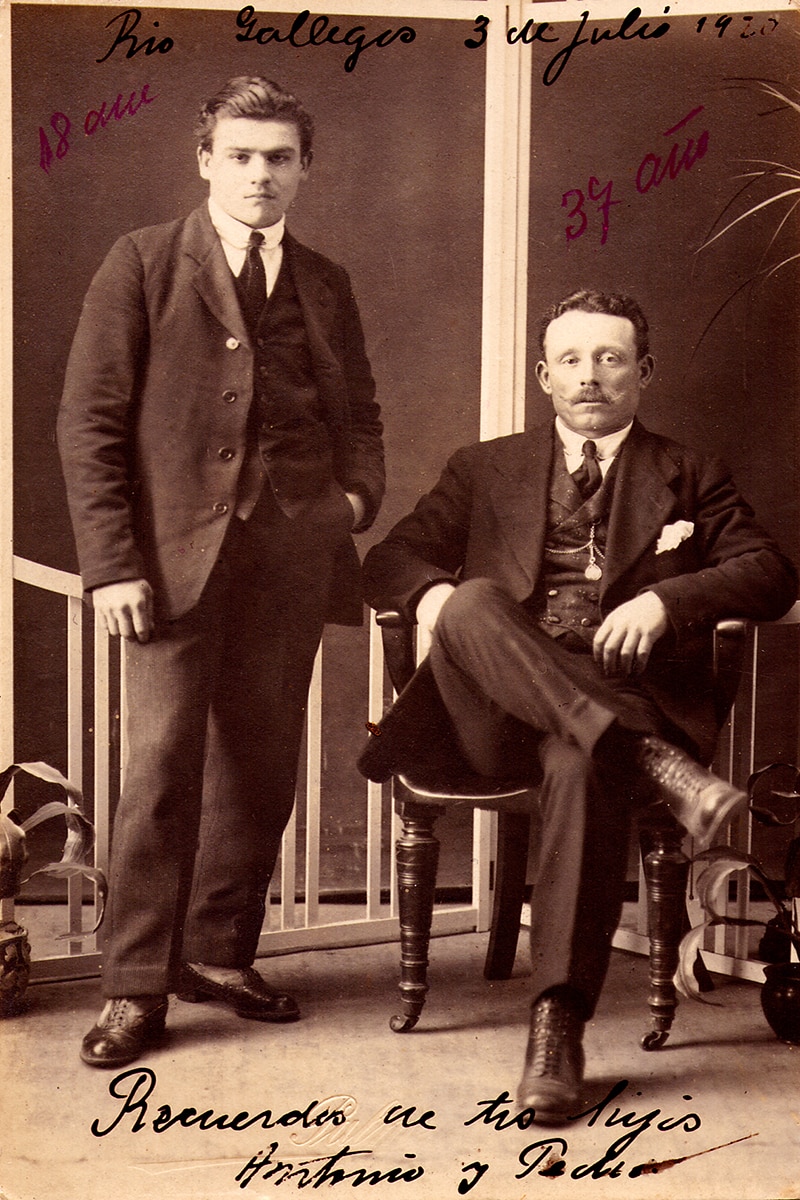

In 2009, Castelli was 96 years old when I started looking for data. He was the one who showed me clues and gave me some photographs, mediating objects of memory that caused a subtle slippage into my dreams. That is why I think that my travels and explorations began first and foremost as imaginary rather than objective and practical.

When I returned to France, I began to plan my first trip to northern Italy. Returning to the region of my ancestors awakened in me a deep curiosity. It was to retrace a path in reverse, of intertwined temporalities; it was to confront history, to build it anew. In those years of research, I found concrete elements (documents) that gave me some historical certainties, although everything was always surrounded by mystery. As I belong to the fourth generation, much valuable information has been lost. However, a partial and incomplete reconstruction offered me the possibility of inserting my artist’s imagination. Here we are in the realm of hypotheses; there are no affirmations, only possible stories, speculations. We imagine, for example, how those trips, those lives could have been. From Roland Barthes’ photographic “ça a été” (that would have been), we move on to “ça aurait été” (that would have been). I based my work on maintaining this state of uncertainty throughout the research process.

Did you feel that the search changed you?

During those years of research, I felt a deep connection with my ancestors, a virtual and, at the same time, close relationship. I established a form of secret and silent dialogue in my travels. Traveling through those regions inspired by oral histories and photographic images gave my artwork an existential dimension. The construction of a narrative memorial that was Reprises became an imaginary territory that accompanies me in my displacements. A fictional transitional space to support the departures and returns. A need, perhaps, to articulate distant worlds, such as here and there, past and present, presence and absence, imaginary and real, those who are no longer here, and those of us who continue to explore this world with wonder.