Towards photobook vanguard

Ricardo Báez is recognized as a disruptive creator: his works not only test the classic conceptions of a photobook but also seek to reconfigure the relationship between design and photography. In fact, in the opinion of the prolific Venezuelan editorial designer, his authorship is as vital as that of the photographers he collaborates with. We spoke with Baez about his most important works, the uses of archiving and artificial intelligence in his creative process, and the end of “visual books” as we know them today.

By Alonso Almenara

“When I think of an idea for a book, I think of how that idea can be systematized: I want it to be expressed in the color, in the format, in the typography, in the compositions, in the overall graphic feel of the book. It’s what I call design thinking,” says Ricardo Baez. For the Venezuelan designer, “an idea that is not systematized is just an occurrence.

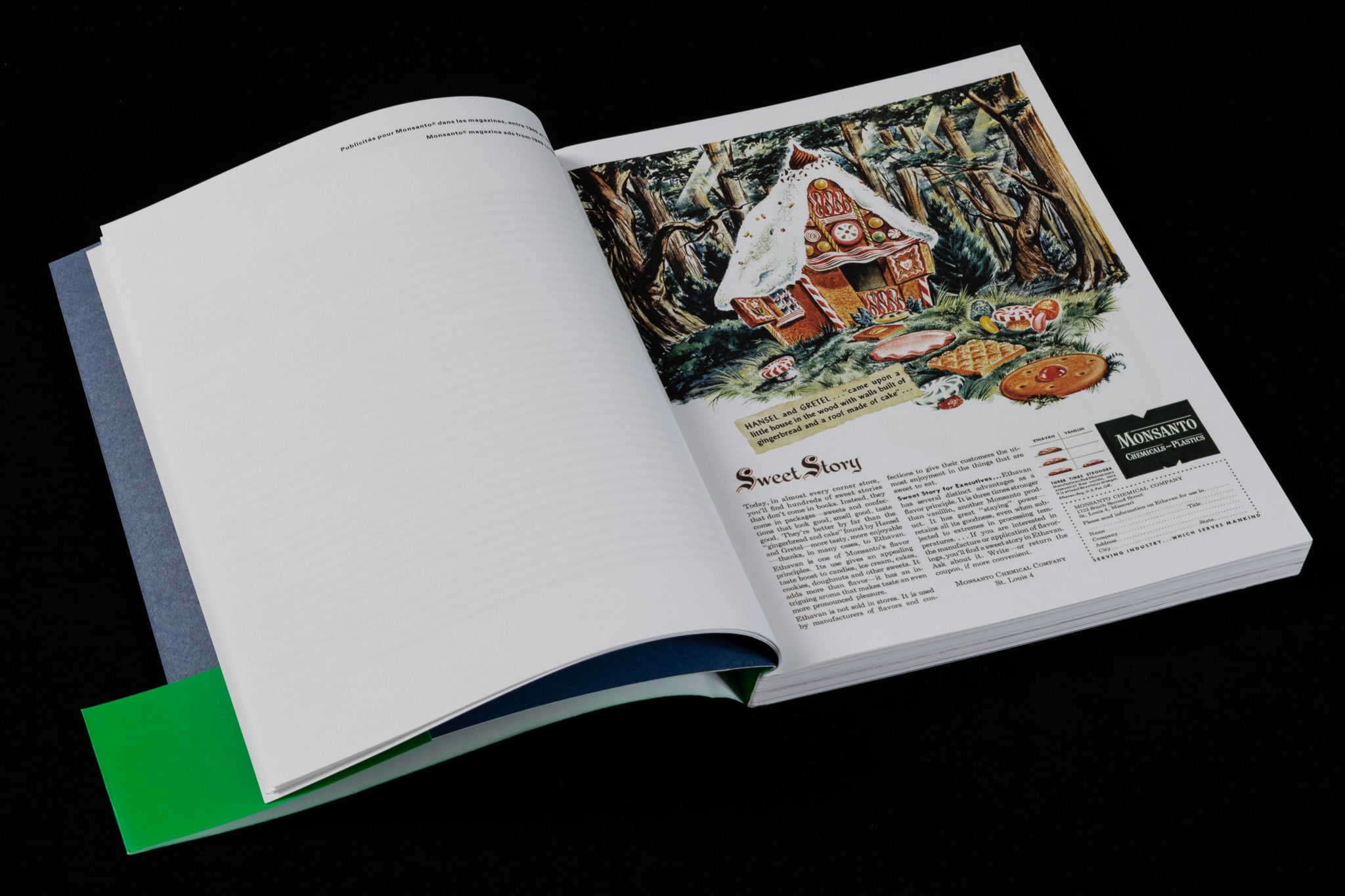

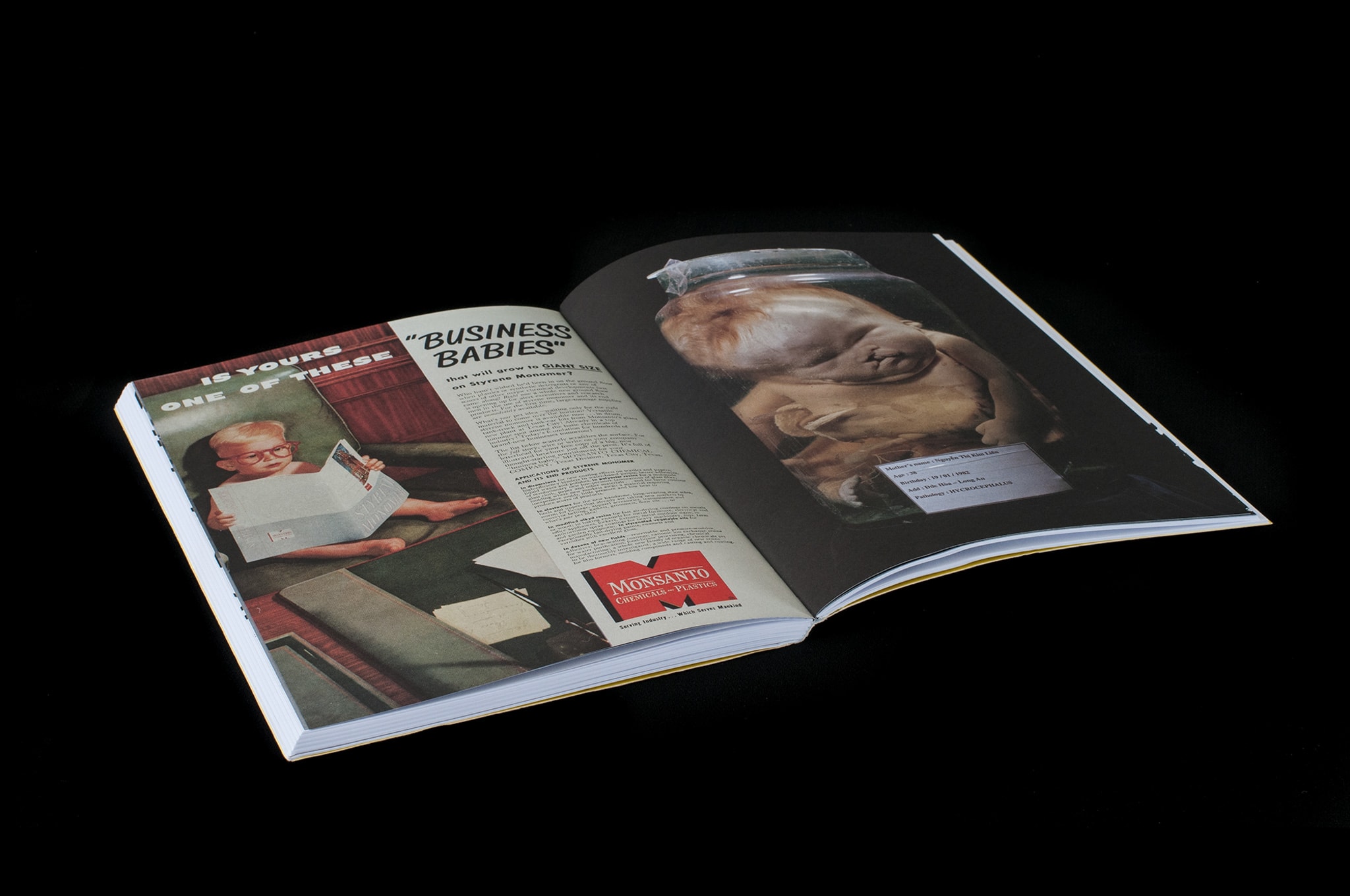

At 39, Baez is a member of the AGI (Alliance Graphique Internationale). His work in the field of photobooks has earned him numerous awards: among them, the Silver Medal at the Latin American Design Awards (Peru, 2020), the Paris Photo-Aperture Foundation First PhotoBook Award 2017 (USA/France. 2017), and the 1st Dummy Award Kassel (Germany, 2016). His most famous designs are Monsanto: A Photographic Investigation by Mathieu Asselin, Fotografía impresa en Venezuela by Sagrario Berti, and Curso/Discurso, a hybrid volume of essay and visual elaboration in which he shares authorship with Gonzalo Golpe and Alejandro Marote.

“The speed with which we read images in the digital world is great,” he reflects. “And I think visual books-and, not just photobooks-help us change that reading rhythm: they are a kind of brake against the unbridled rush of images.” Baez increasingly appreciates that different way of reading: “That could be the great contribution of visual books in an era in which the book itself seems to be an object out of place and out of time.”

In this conversation, Baez values the role of design and new technologies in photography’s transformations in recent decades. He also reflects on the works that marked his development as a designer and openly discusses the friction he has encountered when sharing authorship with photographers.

By Andrea Hernández Briceño

What initially attracted you to the world of the photobook?

I’ve always been interested in photography. When I was 17, I founded a digital fanzine about skateboarding with my brother in which we both took photos, wrote, and did the design. It was very interesting because it allowed me to test what I wanted to do with my life and understand if I was a designer, editor, photographer, or writer. That’s how I discovered that what I was most interested in was editorial design because it is an activity that allows me to shape a publication by influencing all its variables, from the visual to the written content: everything must work in unison.

From that experience, I was in permanent contact with photography: first, I worked as a producer for many photographer friends, and then I started to design photo books. That’s when I realized that the technical reproduction of a photograph opens an immense field of possibilities. It is not the same, for example, to reproduce an image in its original color, to ink it in a specific color, or reproduce it in Riso, offset, or photocopy. And in photography, it is not the same as in painting, where there is always the fear of distorting the original piece because what is the original in photography? The negative? In analog photography, what about digital photography? Is it the RAW? It doesn’t matter. What matters is that indeterminacy can be productive. And every book I design allows me to ask myself again what reproduction can bring to photography for better communication of the idea.

When I approach a project, I first ask myself: what do we want to communicate, and how far do we want to take this project to expand photography? What interests me about editorial design is working with images that somebody will transform according to context, function, or intention.

Let’s talk about the projects that have been important in your development, especially those that changed your understanding of photobook design.

The big project that made me think I should dedicate myself as much as possible to designing this type of book is Monsanto: A Photographic Investigation by Mathieu Asselin, not only because of the importance of the subject and the author but also because it was with this project that I realized the capacity of the photobook to integrate design and photography radically. In addition, since this book, the author has changed his way of conceiving each project to the point that he now works more from design thinking than photography.

It was an exciting evolution because originally, it was a photographic reportage that, although it used archive images, was 80% author’s photography. Then the project accumulated other types of material, such as data from the Stock Exchange. And that is expressed through the design. So, beyond the recognition that the book has received and beyond the subject that is so strong and so important to be known, this book meant a lot to me because it put me in a situation that allowed me to prove -to me, to the author and the whole work team- to what extent design can be the element that articulates the general conception of a photo book.

That is always under discussion regarding how much design is acceptable. Sometimes, design is a hindrance, or the designer is an egomaniac who wants to assert their ideas above all else. I don’t see it that way. Design thinking is a contribution as long as it operates with the author’s consent.

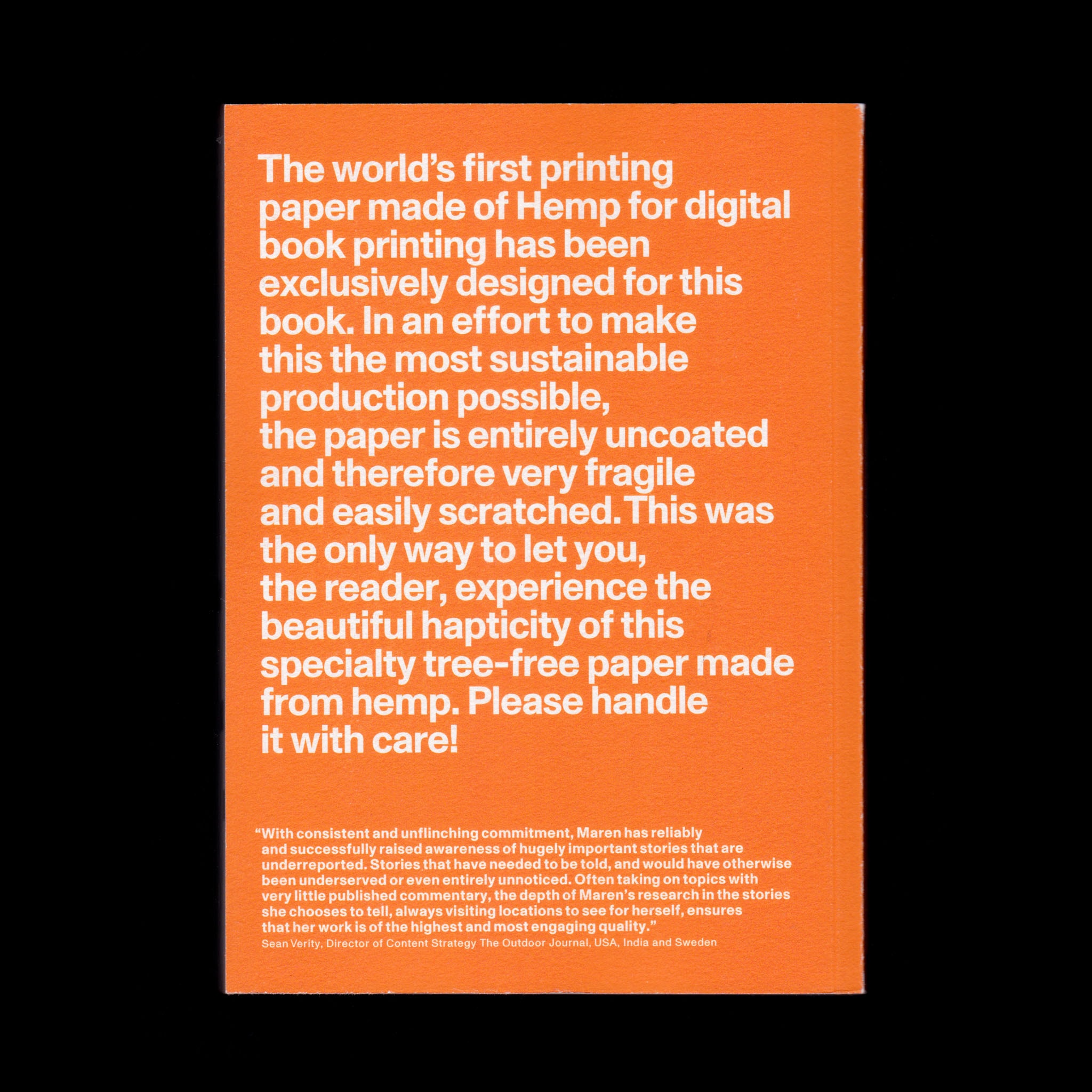

I understood all that with this book, which is why it is so important to me. It is also essential for another reason: I have been transferring that form of design around a complex investigation to books of a more timid kind of a different kind. I always motivate authors to deepen their research and use all the expressive elements that can help communicate ideas. For example, last year, I designed a book called H is for Hemp by German researcher Maren Krings, whose message is that hemp has enormous potential as an industrial element and can help mitigate climate change. It is a book made up of photographs taken by the author but also includes a significant amount of information gathered by Krings over decades of work as an activist. It was quite a challenge to give shape to that project, and the solution we found was to turn it into a kind of dictionary or user’s manual. It seemed to us that this was the most appropriate: the texts follow an alphabetical order that gives an account of the potential of hemp in areas such as construction, gastronomy, etc. We abandoned the idea of a narrative sequence to orient the material toward direct use.

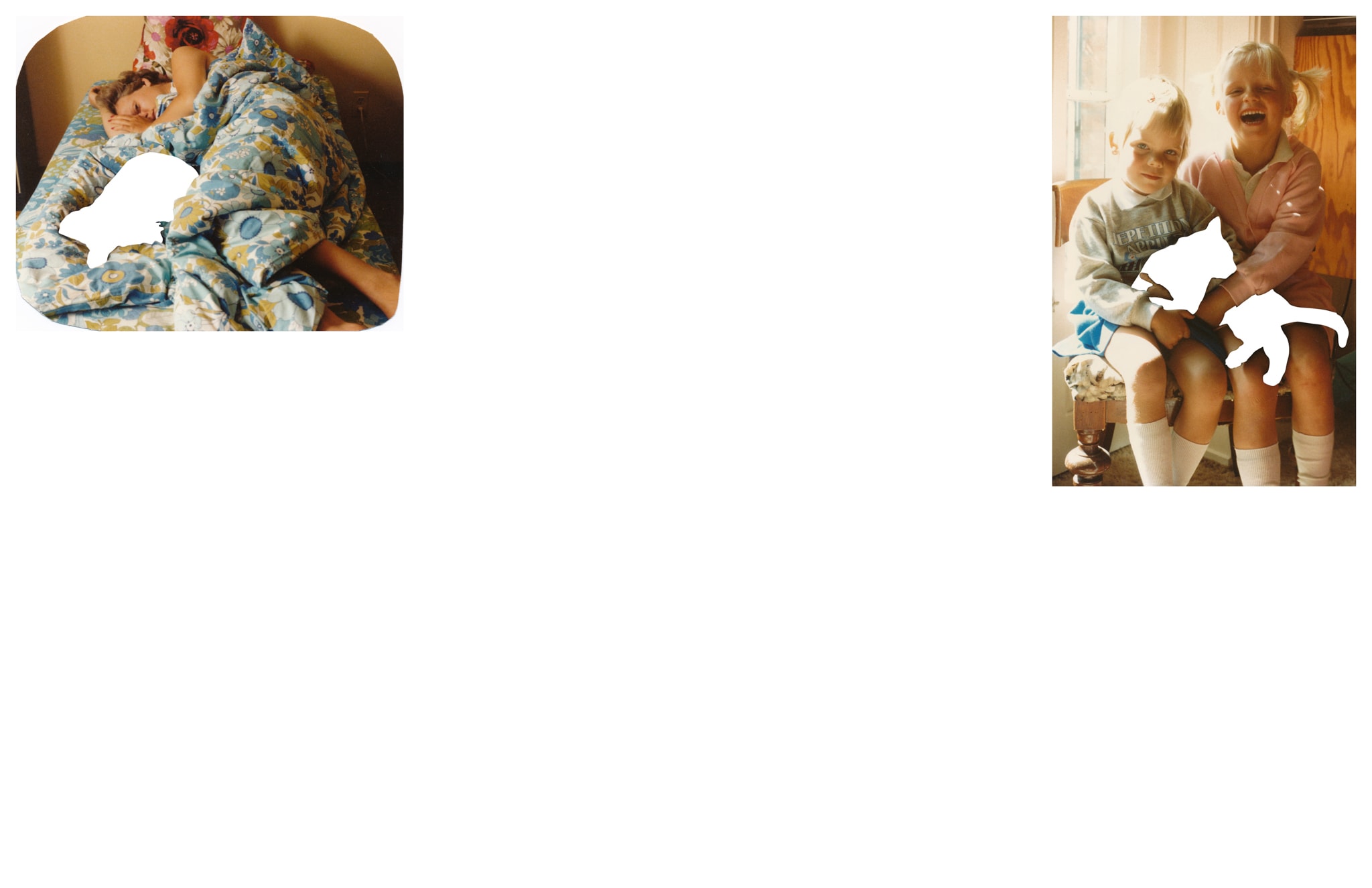

Finally, I would like to discuss a third book that has yet to be published but is already in print and has just won a prize as a mock-up at Fiebre Dummy Award Madrid. It is by Danish author Julia Mejnertsen and is called HUN, which means “she” in Danish. The story relates to Mejnertsen’s mother, a professional animal hunter in Africa. It creates an intense conflict for the author because she adores her mother and sees her as a hero, but she understands that what her mother does is abhorrent to many people. And the book is very introspective, even to the point that it leads one to question why I believe what I believe. And, above all, why we should respect those who don’t think like we do. In other words, it is a book about intolerance.

But it is also the first project in which I have been so involved personally. It also generated many conflicts for me because I disagree with the killing of animals, but at the same time, I eat meat, I kill cockroaches, and, in short, it led me to question many things. And it also led me to ask myself to what extent the emotional connection motivates me to get involved as an author in a project because I also feel that I am an author within the work team. And if I don’t get emotionally involved, I can’t generate anything that I do.

“In the world of photography, there is a certain fear of letting in elements that come from other fields and that may infringe on the authorship of the photographers. The central question when approaching a project is: what best communicates a certain idea? If the photographer considers that his authorship should be in the foreground, it is a problem, and the communication may be truncated. For me, dialogue should take precedence. The idea is to generate collective situations in which the idea of authorship takes a back seat.”

Can we talk about the production aspects of this latest book? I’m especially interested if you can share with us some of the ins and outs of your creative process.

Every element of HUN has been worked on in-depth, from the typography, in which I went to a font house in Denmark to see what a Danish letter looks like. And we have incorporated a great variety of material: there are texts generated by ourselves, there are questions, and I even worked with an illustrator (Mauricio Vivas) who I asked to draw what an elephant sees when it is hunted. There you begin to understand that the production process of a photobook is almost like that of a film: it’s not something that involves one or two people; there is a whole team that can include a curator, a colorist, an illustrator, a writer, etc. And those are the projects that interest me most now, the ones that give me the possibility of having that permanent dialogue with people from other specialties, and not only with the author because the author is not always the most objective person when it comes to deciding what to do with the material. In HUN, the process lasted two years, during which we did many interviews with the author; she even recorded several hours of video conversations with her mother. There was a great deal of analysis to arrive at this book.

One aspect that catches my attention in your work is your interest in the history of the photobook. You have even made photobooks about photobooks.

To date, there are already about fifty books that compile photobooks. I have had the opportunity to make two: Fotografía impresa en Venezuela and CLAP! 10×10 Contemporary Latin American Photobooks: 2000-2016. These kinds of publications are crucial. I use them constantly, and they help me a lot in my research. Now I’m working on a new project deconstructing a famous book here in Venezuela called Sistema Nervioso by Barbara Brändli, John Lange, and Román Chalbaud. Martin Parr has reviewed that book; it has been included in photobook exhibitions; it appears in Horacio Fernandez’s book on the Latin American photobook; that is, it is a milestone in the history of the photobook in the region. And the particularity of Sistema Nervioso is that Brändli, the photographer, gave Lange, the designer, her photos, but she did not participate in the process. So the book is completely orchestrated from the design. Lange put together a sequence in which she distorted the images, cropped them, and flipped them, turning the photograph into graphics. And then she commissioned the text to Chalbaud, a playwright, who conceived the work as a performance in which he made notes on the model, then closed the book and never opened it again.

It’s a very crazy way of working, a method that I could never apply. But I got in touch with the C&FE Collection, which acquired all the original material of Sistema Nervioso, and even with the printer of the book (the master printer Javier Aizpurua), who explained to me the bizarre techniques that Lange used in that section. My idea was to make a book that compares Brändli’s original photographs with the final book. I think it is a fascinating work, mainly because the history of the photobook has usually been approached from photography but not design. And I believe it is essential to highlight that other aspect because whatever they say if there is no design, there is no book.

You were telling me that the photobook designer, from your perspective, is also an author. I imagine that this inevitably generates tensions with the photographer. Is that so? Are those tensions productive?

In the world of photography, there is a certain hermeticism, a certain fear of letting in elements that come from other fields and may infringe on photographers’ authorship. I want to speak frankly about this subject, which is a very delicate one. The central question when approaching a project is: what communicates a particular idea best? If the photographer considers that his authorship should be in the foreground, it is a problem because the communication may be truncated. Then, dialogue should take precedence. And the idea is to generate collective situations in which the idea of authorship takes second place.

I am an author not because I impose my points of view but because I put forward situations that complement another author’s ideas. I see it as a sum of authorship. To illustrate this point in class, I always use McLuhan’s book El Medio es el Mensaje as an example. It is a book in which McLuhan collaborated with the designer Quentin Fiore. Without Fiore’s contribution, it would not have had the impact it had because it is 90% image. There was a conjunction of authorship to achieve better communication.

“Possibly camera-generated photography can no longer be cutting edge. There are books made entirely from archival photographs that tell a story better or communicate an idea better than a book made from author photographs would. And the avant-garde of the photobook is perhaps just that: an exploration not of what the photograph says, but of how the photograph narrates.”

I want to end this interview by talking about the current state of the photobook. How do you perceive its development in Latin America?

Something that impressed me a lot when researching for the book CLAP! 10×10 Contemporary Latin American Photobooks: 2000-2016 is the quality of the work being done in the continent despite how difficult distribution is and how little recognition there is in this field. And I must say, moreover, that since I finished that book until today, many new publishers, workshops, and events have emerged that have made the photobook much more established in the region. What I want to highlight, above all, is the variety of forms that the photobook has adopted: it has gone to all extremes, from the fanzine to more elaborate publications.

In Brazil, for example, photo books of the highest production quality are being produced. That is an essential achievement because the book industry in Latin America has always needed to be more technically deficient. In other words, new printers and production approaches are emerging thanks to this type of project. Another interesting case is the Gato Negro publishing house in Mexico, which produces its books. The important thing is that there is an upturn in this field, and I believe that there is no longer that self-imposed limit that we must copy a foreign production model to be able to do things but that we are doing things the way we want and the way we can.

Do you consider that there exists a vanguard of the photobook today?

It’s a complex question that I would have to answer in parts because the photobook is made up of different components. And it is necessary to talk first about the avant-garde of photography because a photobook cannot be avant-garde if its content does not follow the same path.

One development that I find interesting is the use of open-access archives that belong to private collections or museums. Today it is possible to obtain images of the highest quality and create technically impeccable publications. Another field that attracts me is the generation of ideas with artificial intelligence, which will pose new challenges for the photo book. I am working on a project in which practically everything has been generated with artificial intelligence, and it is a children’s book. By this, I mean that the development of these technologies is not predetermined but will be a consequence of the use we make of them.

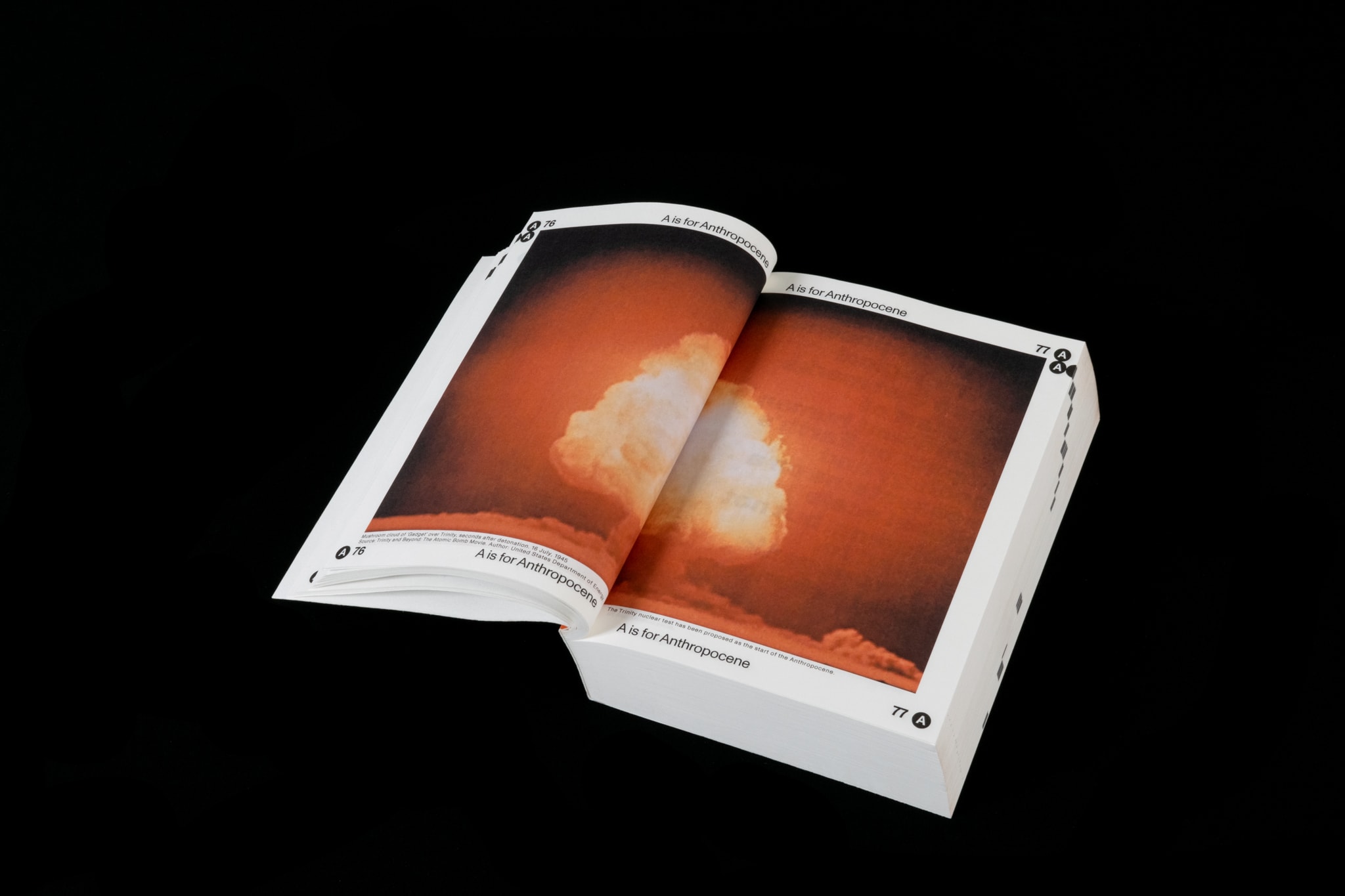

Something that greatly affects my work is the idea that possibly photography generated with a camera can no longer be avant-garde. There are books made entirely of archival photographs that tell a story or communicate an idea better than a book made with photos by an author. And the avant-garde of the photobook is perhaps just that: an exploration not of what the photograph says but of how the photograph narrates.

On the other hand, the technologies that make it possible to generate images from text make me think that it no longer makes much sense to speak of “photobooks.” The term “photobook” implies that the publication includes photographs, but nothing is self-evident in this field anymore. I prefer the time “visual books,” which is less restrictive. This reminds me of a Gato Negro publication: Nostalgia, by David Horvitz, a book about photography that does not include photographs but only descriptions of digital photos that the author has deleted from his hard drive. It may not technically be a photo book, but to me, it’s an excellent photobook that rethinks the idea of the image and the idea of the photo. And I think the future of this kind of publication goes that way, too: it is to get rid of that purist idea of photography.