The traditional and the contemporary intertwine in the work of the Peruvian artist, current exponent of the Sarhua boards, a symbolic form of Ayacucho art. In her hands, Andean folk art became fertile ground for telling stories of female liberation.

By Alonso Almenara

The first time Venuca Evanán was invited to participate in the Art Lima fair- the most important of Peru’s contemporary art circuit- a guard prevented her from entering. It was 2018. She was with her father, the legendary artist Primitivo Evanán, and both were dressed in traditional costumes from Sarhua, their hometown in Ayacucho, Peru’s southern highlands. Venuca had a special pass to participate in the inauguration as an exhibitor of the Ministry of Culture stand. It was not enough: immediately, they told her she was not welcome.

Discrimination is something Venuca has had to deal with all her life. Her family moved to Lima in the 1980s, fleeing the violence that tore Ayacucho apart during the dark years of the Internal Armed Conflict. Although today she is considered one of the leading exponents of the Sarhua tablas, she notes that, until her parents’ generation, this traditional art was practiced only by men. The origins of the tablas date back to colonial times when the writing of the conquistadors began to be combined with Andean symbology. Made with natural pigments applied with bird feathers on maguey planks, the boards tell stories that are read from top to bottom, articulated in scenes featuring figures reminiscent of the illustrations of Felipe Guamán Poma or the watercolors of Pancho Fierro. Their role is not only decorative: in Sarhua, these objects are given to families every time they build a new house, in a ceremony in which the whole community participates. They make up a collective memory, where each Sarhuino is portrayed doing what he or she likes or is identified as a beloved member of this small Andean town.

Venuca’s work honors that tradition but she is not constrained by it. Her pieces speak of migration and social injustice and have female subjectivity energy that is not afraid to investigate her traumas, desires, and aspirations. When Venuca finally joined Art Lima, the initial displeasure was overcome by the intense impact of contemporary art. “It broke my way of expressing myself through painting,” she recalls. “I understood that I had the freedom to paint not only on boards, as I was taught, but that I could do whatever came to my mind. She understood, too, that she would have to fight to have her work recognized on an equal footing with that of her colleagues. “I asked myself: Why is this considered art and what we do is not? Why do these works cost so much while we get a bargain?”.

Venuca Evanán at the opening of the exhibition Riqchari Warmi / Awake woman. Photo: Victor Idrogo

Venuca Evanán at the opening of the exhibition Riqchari Warmi / Awake woman. Photo: Victor Idrogo

The exhibition title is taken from the work with which you won the ICPNA Contemporary Art Award 2020. How was the idea for that piece born?

The idea came at the beginning of 2019 when the Municipality of Sarhua hired me to give painting workshops to children. After living in Lima for several years, I returned to settle in Sarhua with my daughter and began to observe my community. I became interested in the Varayuq, the communal authorities carry command canes painted with traditional themes. I began to ask myself: Why is it that until now, there are only male Varayuq? Why is it believed that Sarhua women cannot also assume authority roles? I talked to Teofanes Pomasoncco, an artist who carves walking canes, and I bought some of them with carved but unpainted heads. I brought them to Lima and intervened in them with my style, returning to the themes I have focused on: the valorization of the Sarhuina, Andean, and migrant women.

The canes that make up the work tell a story, right?

That’s right; each cane shows a different scene. I took as a reference the visual reading of a Sarhua tablet. In the first one, we see mermaids under the moon playing musical instruments that are usually reserved only for men. In the second, I painted scenes of psychological, physical, or economic violence directed against women. I also painted rapes: these are things that happen in the communities, but nobody wants to talk about them. On another stick, I painted empowered women getting involved in politics, fighting alongside other women to liberate themselves. And the last canes shows women healing emotionally through their connection to the land. It is a work in which I have used a medium linked to ceremonies led by male authorities to tell stories of women’s liberation. In the exhibition, I installed the result next to a painting entitled Las Varayuq, in which I portrayed a group of Sarhuina women carrying those canes.

Have you ever felt that your community did not receive your ideas well?

Of course, I did. Conservatism in Sarhua is strong. Even my father, in the beginning, didn’t like me painting murals. And what bothered him the most were the erotic pieces. He would look at those works and tell me: “what are you doing? You’re crazy”, jokingly. But finally, he understood.

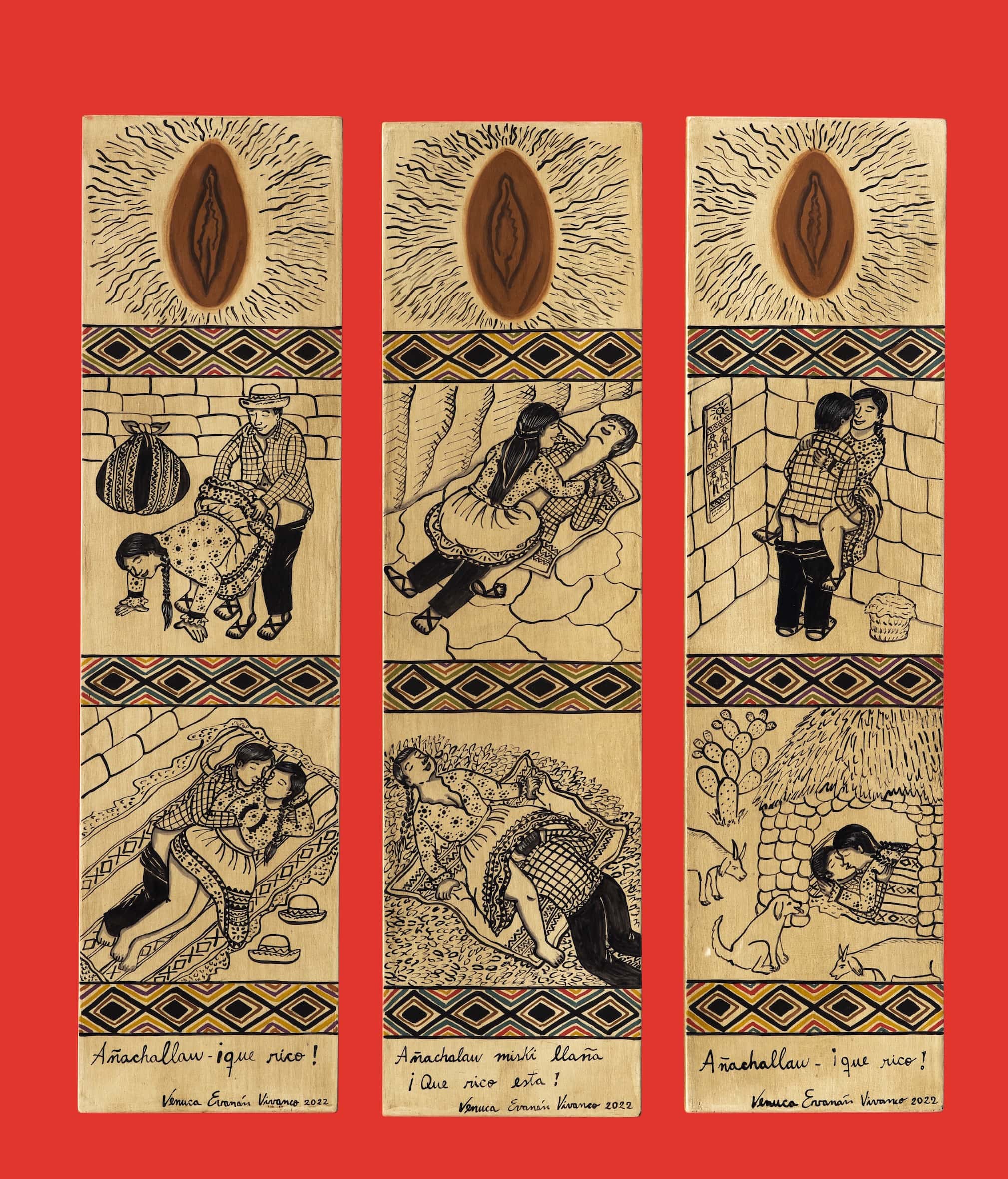

Venuca Evanán, Añachallaw / ¡Delicious! (2022). Photo: Daniel Giannoni. Cortesía del ICPNA

Has the reaction of other members of the Association of Popular Artists of Sarhua been as positive?

The truth is that I prefer to work in my workshop, where I have the freedom to paint what I like and what I want to show without consulting anyone. I don’t know what the Association thinks. But what I do know is that their daughters are aware of my work. I think, for example, of Violeta Quispe, who began to paint female themes due to my initiative. I not only paint but also do activism so that more women get involved with their heritage and can express themselves artistically.

In 2019 you posted photos on your social networks of a work that references normalized rape in your community. Many people asked you to take down the post. What exactly happened?

That piece is called Erotismo sarhuino. It is shaped like a uterus and shows scenes related to female sexuality. In one of them, I refer to a common practice in Sarhua and perhaps in other Andean communities: men get women drunk to have sex with them. They consider it a game. They don’t want to understand that it is rape. But if it were a game, the girl should be able to decide whether she wants to play or not. Now, the piece does not stop only at the rebuke. Another scene is a talk on comprehensive sexual education, where Sarhuinos and Sarhuinas are gathered in front of a blackboard with nurses, talking freely. For me, it is essential to be able to talk about these issues so that sexuality takes place in an environment of trust, respect, and mutual care.

Venuca Evanán, Erotismo sarhuino (2019). Photo: Victor Idrogo

Detalle. Foto: Victor Idrogo

After that experience of rejection, did you consider abandoning that theme?

I thought maybe I should be more sensitive to the Sarhua community. But I decided to resume these works after seeing in the news that they were destroying erotic huacos (ceramic pieces) in Trujillo. I was surprised by the violent rejection of these pieces that were considered inappropriate. There was an inability to see them as part of our history. It saddens me to see how artists’ work is trampled all over. But before I took up the erotic pieces, I had to think carefully about how to approach sexuality so as not to be disputed by my community. I had already been told that the things I paint don’t happen in Sarhua. So I decided to represent myself, to do my erotic self-portrait. I painted my experiences in Sarhua. They can no longer refute that anymore. And I will continue to paint these subjects. Now I even have requests from people who want me to paint erotic portraits of them.

Speaking of social media, I have at home a piece you created during the pandemic that you were selling on Facebook. It is part of a series of fifty small self-portraits. It’s an exciting work, which also includes Facebook icons.

The truth is these works have helped me a lot to support myself during the period of confinement, in which the spaces for the exhibition/sale of artworks were closed. I remember that I was worried. The gallery wasn’t calling me, I had no savings, and my projects had fallen through. I didn’t even have materials in stock. So I grabbed the boards I would make traditional boards with and cut them into smaller segments. I started to paint myself with my face mask because that’s what we used to go out. And since the medium I used the most for information during confinement was Facebook, I portrayed myself as a social media post. I think that is the story of many in times of imprisonment: we looked at what others were doing through networks. I made fifty units so I could sell them at an affordable price. My reference was engraving, but in my case, each painting was hand-painted, and each mask has a different design, so each portrait is a unique piece. I am very fond of those works because they have helped me to be resilient with art.

Venuca Evanán, El arte en tiempos de cuarentena – Autorretrato (2020). Photo: Victor Idrogo

Another exciting aspect of your work is that you have pieces that address the entry of Sarhuin art into the contemporary art world. Some of them refer to MALI, and in another, you portray yourself at the Art Lima fair. In the latter, if I’m not mistaken, you have portrayed yourself looking at a work by Genietta Varsi. What caught your attention?

Genietta has a simplicity that I appreciate very much, which is not common in that world. A contemporary art fair is unlike a craft fair, where we all help each other and freely discuss our techniques. At Art Lima, I asked questions, and they didn’t answer me, maybe because they saw that I wasn’t going to buy anything. I liked Genietta’s work: it is a self-portrait that questions the standards of feminine beauty. I also painted a piece by Alberto Borea, a broken refrigerator. That piece intrigued me because I had difficulty understanding how a broken appliance, which one would normally throw away, can be art.

Venuca Evanán, Autorretrato – Art Lima (2018). Photo: Victor Idrogo

Do you feel your work has changed after this contact with the contemporary art world?

The materials have changed. In addition to working on wood plates, I now use sticks and experiment with textiles and embroidery. I am also practicing a bit of sculpture. My use of color has changed: I no longer respect the traditional chromatic palette of Sarhuino art, but I use everything. For example, the erotic piece we talked about is in black and white. But that is a nod to the first Sarhua boards, which I did not paint in color. It’s a mix between tradition and contemporaneity.

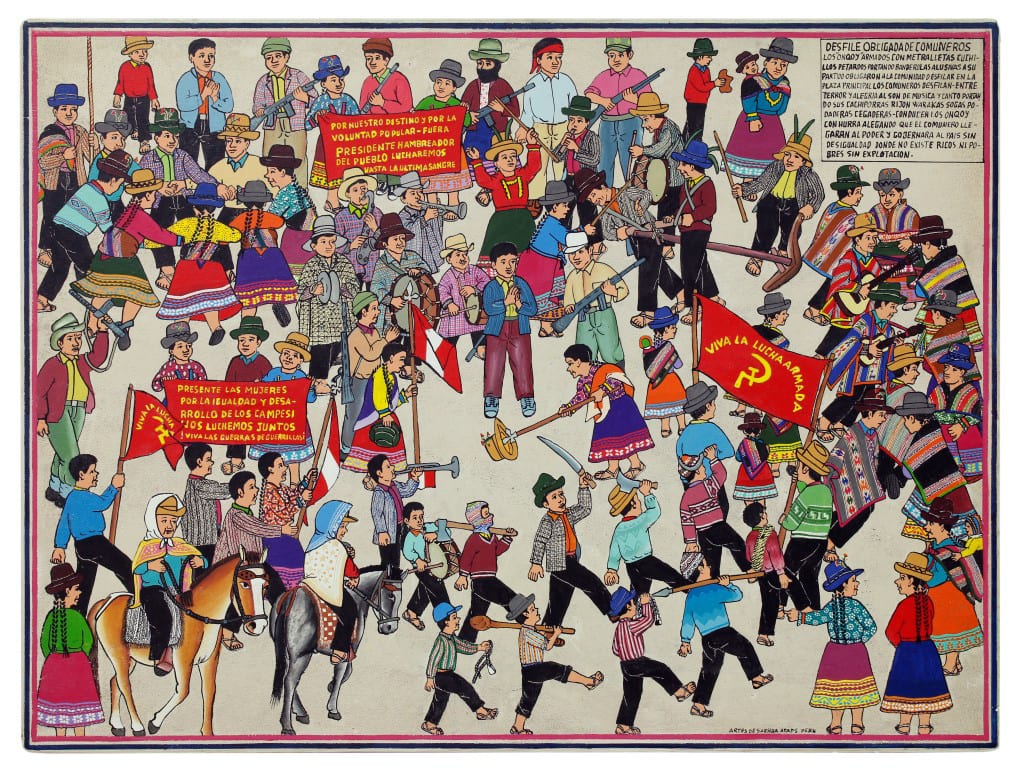

Asociación de Artistas Populares de Sarhua, Desfile obligada de comuneros. De la serie Piraq Causa (¿Quién es el causante?) (1990-1998). MALI

In 2018, MALI exhibited a series of Sarhua boards that portray the violence your community suffered during the 1980s. That series, titled Piraq Causa, sparked an extreme controversy. A press sector accused its authors, the Association of Popular Artists of Sarhua, of apologizing for terrorism. How do you remember what happened?

The newspaper Correo published a front page accusing us of being terrorists without consulting us about these works’ meaning. Then journalists from all the media started calling us, and we didn’t know what to say. One told us directly: “Confess, you are terrorists.” I got scared and hung up the phone. It was unbearable. I was worried about my dad, who suffers from blood pressure. We prevented him from reading newspapers or going out in the street. Besides, I was painting replicas of some of those pieces for the Vancouver Museum. I had to hide everything under my bed. I was afraid the police would suddenly arrive. That night we saw that on the program “Beto a Saber” by Beto Ortiz, they were talking about the Sarhua boards. Excited, we thought they would defend us, that people would know the truth. But no. Beto interviewed members of Congress who understood nothing about art, so they would talk about works they had not seen. The journalist was misrepresented and defamed without any conscience. They do not consider their words’ effect on the Ayacucho population. It is a community that has suffered countless fits of abuse by terrorists and the military.

Detalle. Foto: Victor Idrogo

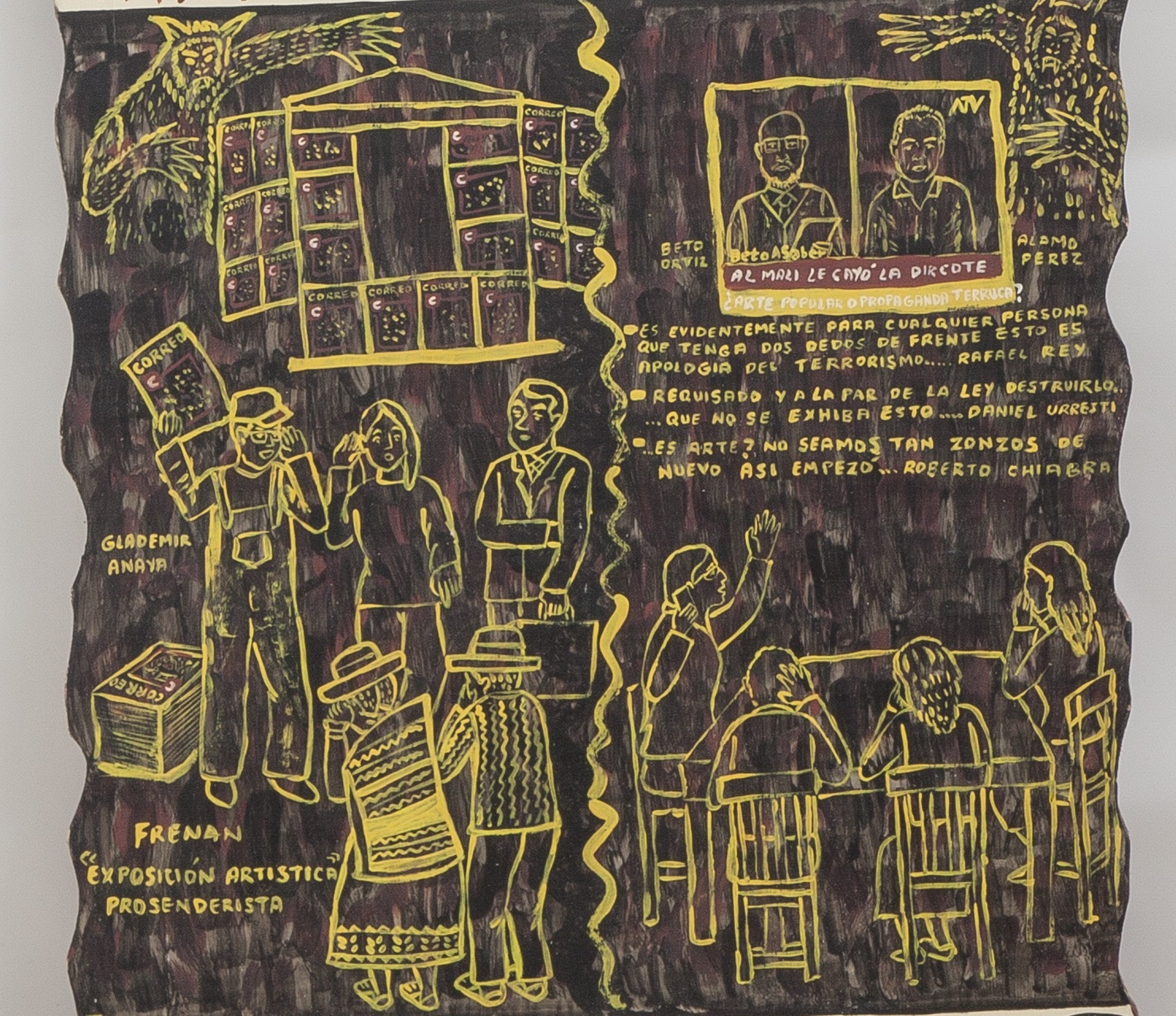

Venuca Evanán, Manchay Puncha 24 de enero (2018). Foto: Victor Idrogo

In response, I painted the work Manchay Puncha on January 24. That was the day certain media began to spread falsehoods about our work. Since we could not talk, I painted. I looked for a bitter wood so that it would never become moth-eaten. I painted the background black and red to reference the dark and bloody moment many Ayacuchans went through.

On the top, I painted some trembling strokes in yellow, referring to the yellow press and the nerves and fear that we went through. I painted the young journalist who published the article in Correo, Beto Ortiz, his reporter, and the words of the members of Congress. In the upper scene, I painted my father with Sarhuino artists who were victims of that time of terror. And in the last scene, I showed what Sarhua is like today: a quiet town that offers art and a lot of culture. There we are, my father, myself, and a girl who could be my daughter or the youth who will continue to spread their heritage through the boards of Sarhua. That is what I wanted to leave for history.