The Women of my Life

Maya Goded is one of Mexico’s most renowned photographers. After more than 30 years of career, she recognizes that hers is a personal and political path traversed by two major themes: women, especially the violence that surrounds them, and healing at the hands of witches, healers, and wise women. For her, each of her projects is also a journey of self-knowledge.

By Marcela Vallejo

“I liked the woman I am.” That was what one of the sex workers with whom Mexican photographer Maya Goded has been working in the La Merced neighborhood for the past three decades said. She said it after watching Plaza de la Soledad, the documentary film product of all those years of effort. Before watching it, she – a trans woman who had participated in the filming with her partner, another sex worker – was apprehensive, almost aggressive. She was afraid to see herself, a sociologist friend explained to Maya. But the result thrilled her: she had not seen herself that way before. She had only seen her partners.

After watching the documentary with each of the participants separately, Maya made a screening for all of them and invited their families. Maya’s father, son of Spaniards, a communist party militant persecuted for his militancy, was very moved by everything he saw and decided to give a speech. Maya says it was a bit long, but he said something that marks this work and others he has done: “Today I met my daughter’s other family.”

When Maya Goded talks about her journey as a photographer, there is a recurring theme: the feeling of having had to fulfill a social and family mandate: to continue the struggles of her ancestors. She descends from a family of Spanish exiles, leftist militants, and women who decided to leave their places of origin, fleeing from various forms of violence. Along with this idea, she is sure about letting go of the mandate that tells that her place is with those who fight. The truth is that even so, Maya found her own political space: women, the violence that surrounds them, but also their wisdom and power.

Although she had done other works before, when she looks back, she finds the beginning of her path as an author when she made Tierra Negra. In the early 1990s, she traveled to Costa Chica in Guerrero. Her interest in the place was born from the stories she heard at her father’s and grandparents’ house when they told the adventures of Uncle Antolin.

Although it was a well-known and intervened place, few photographers and researchers had been interested in the population now recognized as Afro-Mexican. When Goded showed her photos, people in town thought she had taken them in another country, perhaps Cuba. However, what she discovered were the women. There she began a path that marks the rest of her work: women, violence, magic, and healing.

In Tierra negra, Maya begins to explore these themes with a perspective that characterizes her work: closeness and intimacy. On the coast, Maya discovered that these women lived their sexuality in other ways, very different from hers. Despite certain freedoms, at the same time, they experienced pressures that the photographer had never felt before: the imminence of sexual violence, the anxiety for virginity, and for occupying a particular place once they began their sexual lives. Otherwise, a woman who was not a virgin at marriage would be expelled from the village, and, in many cases, her only destiny would be prostitution in neighboring places.

Maya has never shown the prostitution photos she took in that first project.

But later, that was a central theme, although it took time to understand why. The biggest project in this regard was the photobook Plaza de la Soledad, published in 2006, and the documentary released ten years later. That work, in the square and the neighborhood of La Merced, involved 20 years of research, friendship, trust, portraits, and photographs of the women who work as sex workers there. In that case, she also found a world crossed by violence.

Pursuing this interest led her down painful and difficult paths. Portraying the effects of this violence-filled her with fear. The same fear that led her, in search of her healing, to rediscover the other route of her path: magic and witchcraft. Undoubtedly, photography for Maya is, above all, a personal path. One in which desires and intuitions are the guides. And in which you build meanings with time and reflection.

How did your relationship with photography begin?

My relationship with the visual began when I was a child. I had language problems, and I found painting a way to express myself. That was my forte and not words. Also, I wanted to do something social since I was little, mainly because that was what my father and uncles did. They were always involved in political issues. I kept hearing stories about my uncle, who was linked to the peasants and was in the mountains, and then guerrillas came from Central America and stayed at my house. So, I heard a lot of things, and I wanted to know more. I wanted to see what everyone was talking about in my house.

When I grew up, I studied sociology, but I also got into art and put together a collage between photography and sociology, something that didn’t yet exist in Mexico. Then, my first impulse was to go to this area where my adventurous great-uncle had died: to the mountains of Guerrero. My dad talked a lot about it, and I had this idea that I didn’t hear well and wasn’t sure of what I was hearing because my mom told me not to tell my school what I heard at home. The children at my school lived a different reality. So I always doubted whether what I heard was true.

For me, to go and take a picture was to create evidence. I no longer believe in evidence, but that’s how I started. I wanted to be close because I needed to understand what my father and uncles were saying and doing. And because I acquired a commitment with them, I am now shaking off.

So you went to Guerrero in search of your uncle’s stories. What did you find?

I arrived there 30 years ago. It was strange for a woman like me, a blonde, to be walking around, just a prostitutes. And besides, women were robbed a lot. There was a lot of violence against women. I stayed in a house and slept with the lady in her bed, and she took care of me because she didn’t want her children to hurt me or anything to happen. I always tried to talk in the villages with the municipal president and with all the men. I would tell them what I was doing there to understand.

It was as if I had become the town’s photographer. They would call me, for example, when someone died. That’s when I learned to relate to people through photos. I learned to play with people to take portraits. It was hilarious. Women had a sexuality that I didn’t, so I played a lot with that in many portraits.

Violence was always present; to go from one town to another, we would go in groups of women, but they all carried a knife. I felt very good with the women, and suddenly, I started to work on prostitution. I have a lot of photos of prostitution from there, which I never took. I was impressed that if a woman was not a virgin, she was automatically out of the community. And they had no choice but to go to the next town to prostitute themselves.

When I showed my photos, everyone first thought it was Cuba, not Mexico. That’s how ignorant they were. Now I believe there is a much bigger opening, but before, not at all. When I see the photos, I say wow, I haven’t changed. I found myself with the same images I have pursued all my life. I’ve changed areas, but it’s still the same. I somehow follow the paths of my family and what my life as a girl has meant.

This is part of Tierra Negra, a project that became a book. At the beginning of your career, you feel that this is where the themes that have attracted you to this day began.

Photography is such a personal path. I have always chosen themes; One thing leads me to another because that’s my thoughts. It’s what I’m living at the moment. So it is personal, and it is very solitary. I take care of it like a treasure. In my case, the subject came and moved me; it was not something I felt obliged to talk about. Somehow, my way of working is linked to intuition.

I mean, it’s not just my uncle who went to the Costa Chica, I want to go there. No. It started as a desire, and I began understanding the meanings. That’s the most beautiful thing about the photo: when suddenly you’ve been there for a few years, you look back and realize that everything has coherence and speaks to you about yourself. In that sense, the photo is a privilege.

This reflection awoke recently; when Claudi Carreras did the exhibition of African Americans and asked me to review Tierra Negra. I didn’t want to. But when I did it, I realized how far I had come.

A while ago, you said that you started working with women and healing in that first project. Why did you become interested in those themes?

Everything went at its own pace, that is, it wasn’t that at the beginning I said: I’m going to do prostitution, then healing. It was very intuitive. I am not rational, my projects come out of things that one is not so conscious of, and then they make sense.

I also learned from the first years of photography that if you go with a very fixed idea, you don’t let life come to you. If you go to check your theories, there is something that doesn’t arrive. The most beautiful thing is that life surprises you, and the construction is in that moment. And from where you are, you discover it.

The most remarkable thing about the photo is what you thought was falling apart. If it doesn’t go through the body, what’s the point? I mean, I can take a feminist theory, a bitch, and of course, I can go out and visually make everything fit together and it’s perfect. For me, that doesn’t make sense. It has to go through my body and allow me a confrontation with feminist theory, with what I thought, my own way of being, and my own patriarchy.

Why so much interest in prostitution?

It took me a long time to realize it, and it was apparent why it was there. That is, it means many things of violence, but it was also a questioning of powerful things that the women in my family have lived through. In the documentary I made in the Plaza de la Soledad about prostitution, I dedicate it to all the mothers…

The prostitution thing was about questioning the good woman and the bad woman. My two grandmothers are different; one was judged by society because she was super sexual, and the other because she was a worker, her sexuality was erased. There were always these things. When I got pregnant, I said how awful. Now I have to play the role of the good mother, which meant a woman’s confinement. And I didn’t want to play it, and I wasn’t interested in that role. I was terrified of it.

In your works about women, Tierra negra, Desaparecidas, Plaza de la Soledad, there is a lot of intimacy and violence. How do you manage to deal with both themes?

Violence is in everything. So, they are affectionate, intimate but also violent relationships. That’s what I’ve learned, and even more so when they are relationships of such a long time. In La Merced, many years of work implied the complexity of relationships and trust. It has been interesting because one is involved in violence. I am with them in one of the documentary scenes, and we are laughing our heads off in the bedroom. They are a couple, a woman and a transvestite, they are sharing with me how in their intimate life, there is violence, and I am laughing with them. Then I see myself in the mirror where I am with the camera appearing in the documentary, saying I am also part of this. I am also here, laughing at the violence they share with me.

Somehow you must think about how far you want to be part of it. I guess it happens to all photographers: there comes the point where you have to decide how far you want to be or how far you don’t want to be. And then the next one is: I took the photo, and I’m going to publish it, or I’m not going to post it.

You experience violence and ethics daily. If you got into a violent zone because you want to understand violence, then you have to assume it.

Your work has traveled along those two paths of women and healing. I think that can be seen in two pieces that, as far as I understand, are related: Desaparecidas and Tierra de brujas. How did that relationship come about?

Desaparecidas didn’t come out of something, let’s say, personal, but out of these searches that you suddenly leave open. One day, I was told by human rights organization. A woman was killed in broad daylight on one of the busiest streets. I was going with human rights, and among the women, there was a man who said he was a client, winning us all over.

I didn’t know well, but something was going on there. Later, in the streets, I discovered that the fantastic client was the pimp. When the girl’s body was on its way to the common grave, some people arrived and said that maybe it was his daughter and, yes, she was from the Sierra. They had changed her papers, her name. I was very shocked by that story.

So I applied for a grant. I started photographing Desaparecidas in 2004. In Ciudad Juarez, I fell in love with my partner, that is, there was a film festival, and we danced for about three days. That’s when I started to learn about the disappearances of women and when I investigated, I discovered that there were many things that I had already seen elsewhere. One point that interests me about prostitution is the violence against women, one of the most common mechanisms is the change of identity. They take away their roles and leave them alone. That is a critical point, and that’s how I connected with the issue of the “Desaparecidas.” It was the most painful issue because prostitution is also painful, but I was there from many perspectives, from workshops to the feminist movement. But disappearances come from another pain. I have a daughter.

“The coolest thing about the photo is what you thought was falling apart. If it doesn’t go through the body, what’s the point? I can take a feminist theory, a good one, and of course, I can go out and visually make everything fit together, and it’s perfect. For me, that doesn’t make sense. It has to go through my body and allow me a confrontation.”

What made it so tricky emotionally?

It’s an issue that was very hard for me. It hurt me a lot. I come from a family that doesn’t believe there is justice; I come from disillusionment with politics. The women who have disappeared are a mockery, which is a terrible thing. Doing that work made me depressed; I no longer believed in the photo. Besides, I joined an agency, and all the pressure was taking away my taste for photography. At one time, my hands became paralyzed.

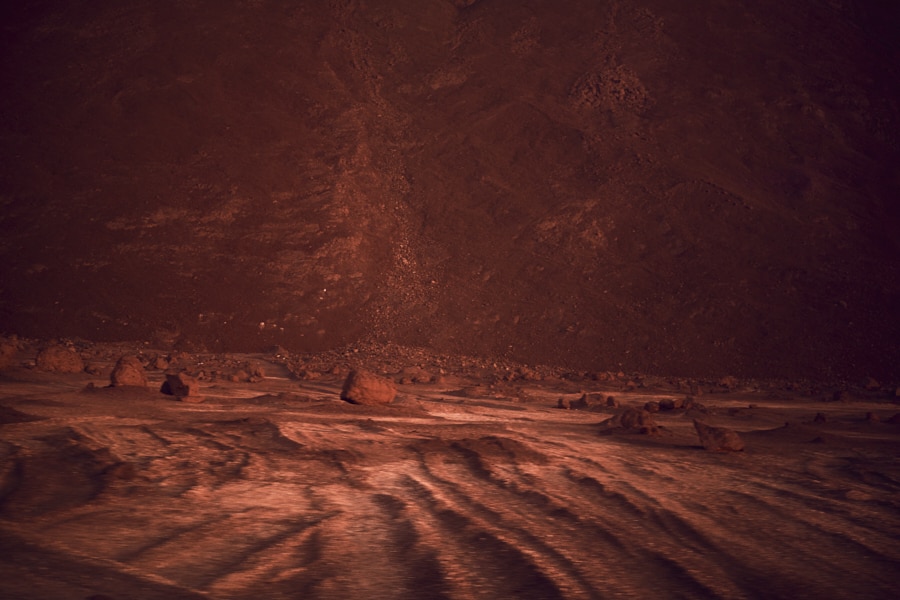

In those days, I was invited to give a workshop in the desert, and they told me about a town famous for its witches. Look, this Mexico has changed, and fear gets into your body if you take a chance. I felt it did. So, there began a whole thing of healing and witchcraft. From there, I began to investigate and made Tierra de brujas, which has become an essential thing in my life, this search for healing wounds.

That is to say, did you find the path to healing in witchcraft?

Yes, there came the point when I didn’t want to see anything else from violence. I could not cope with so much. When my father died, I understood there was a commitment, and I felt I had to do something substantial socially. But suddenly, I didn’t want any more darkness, and that’s how I opened the walls and let some light in. So I started to look for curanderas, and now I am very involved in understanding that if we don’t change as individuals, how can we make a change?

With that change, I went to the mountains of Oaxaca and learned a little bit with several healers. That is, it was a little bit about massages, plants, about different things. I decided to turn everything around because I take pictures and am also learning.

Do you feel you managed to let go of fear in this healing process?

Fear is an exciting topic in my life. I’ve been afraid since I was a little girl and I’ve been looking for it. It hasn’t paralyzed me, but it’s more like a thing of going out and wanting to see it. I like to look at things head-on, even if I’m afraid, to see what’s going on and understand it. It’s part of everybody, although it gets into your body terribly. It’s easier to say that the bad is outside, but that’s the human being. In Ciudad Juarez, I saw that we all have that inside, and I was afraid of what we could become. What I like about the curanderas is that they know how to navigate in the midst of this. I think it’s part of life, and we have to see it and understand it, and that’s it.