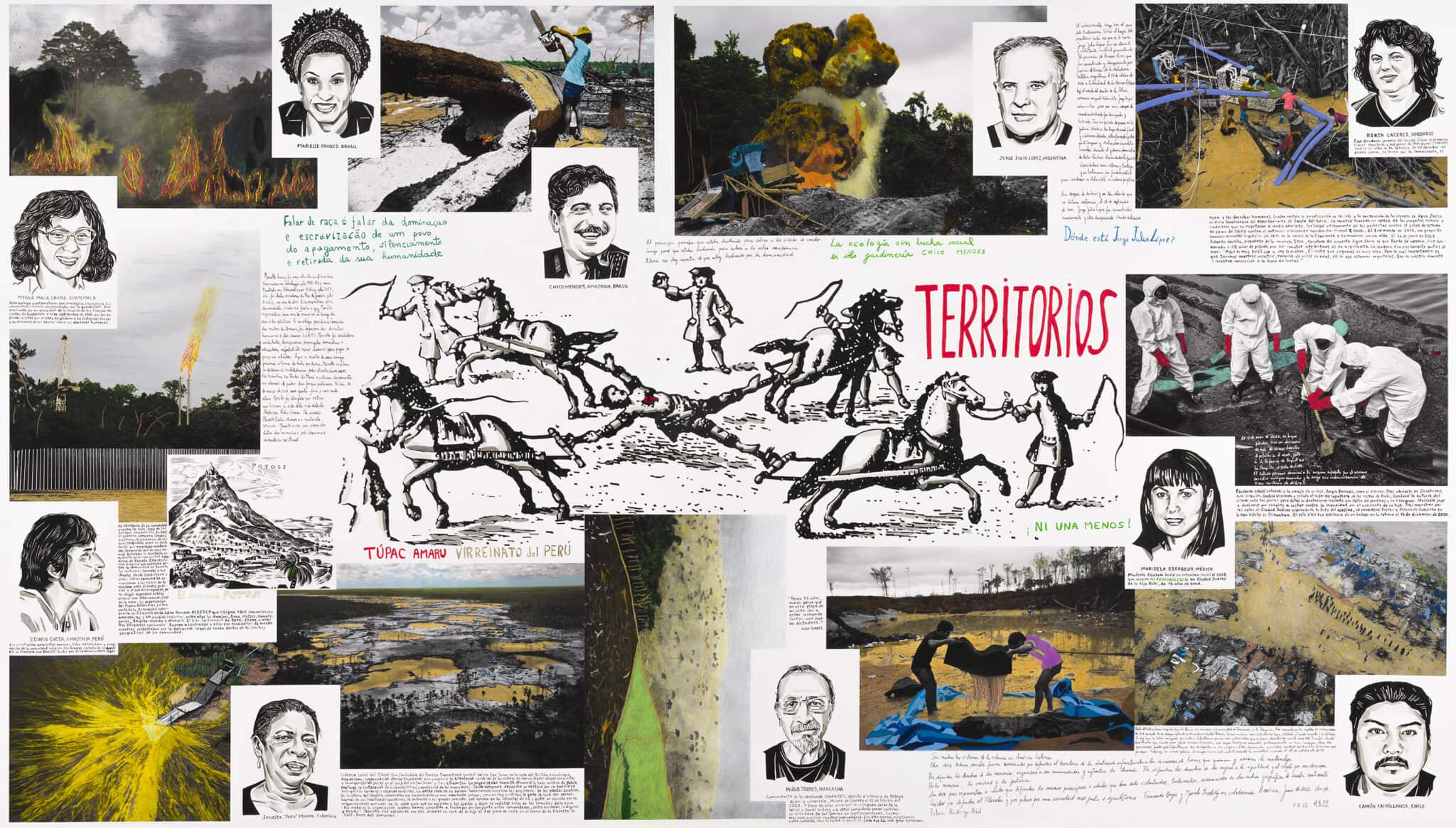

A mural for land defenders

Fernando Bryce and Marcelo Brodsky collaborate in Territorios, a large-format work that combines drawing and intervened photography to pay tribute to social activists murdered throughout the continent. The result inaugurates a new stage in the visual searches of both artists.

By Alonso Almenara

Marcelo Brodsky (Buenos Aires, 1954) is synonymous with controversy for the new generations of Argentine photographers. His early works positioned him as an innovator of Latin American photography and a human rights activist. La Clase –the work that kicks off his photographic essay Buena memoria- is perhaps his most emblematic work. It is based on a portrait of the first-grade high school class that Brodsky attended during his time at the Colegio Nacional de Buenos Aires. The black and white image (1967) has been enlarged and intervened with color annotations that tell the story of each classmate, two of whom disappeared during the cruelest period of Videla’s military dictatorship. Their faces are inside a crossed-out circle: a gesture that combines the innocence of the childish stroke with the terror that would ensue years later.

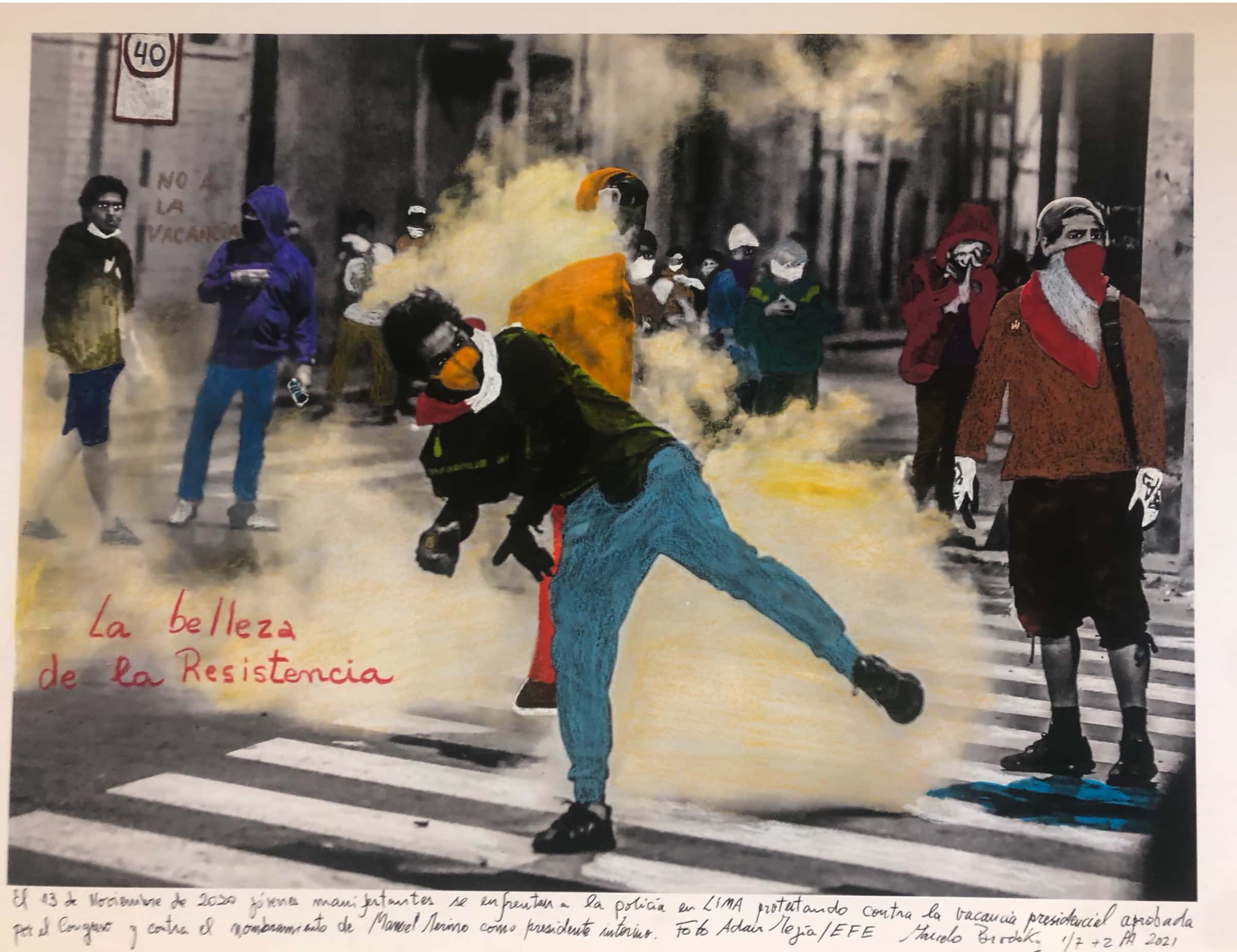

Since those days, Brodsky has remained faithful to that aesthetic that mixes intervened photography and a permanent denunciation of state violence. But his defiant attitude, treatment of other photographers’ work, and use of color in images charged with violence and aspirations for social change have earned him numerous detractors. For his critics, Brodsky moves dangerously on the line that separates activism from the instrumentalization of social struggles. This trait may have intensified in recent years: the artist has stopped using archival photographs to incorporate a “real-time” record of social outbursts in the region. There are, for example, the series dedicated to the National Strike in Colombia in 2019 and the work Jornadas de noviembre, which he produced four-handed with Fernando Bryce (Lima, 1965). The latter documents the large demonstration that occurred due to the dismissal of Peruvian President Martin Vizcarra, and his replacement by Manuel Merino at the end of 2020. An event ended with the death of two young men, Inti Sotelo and Jack Bryan Pintado, at the hands of the police.

Projects such as these generate complex questions: Has Brodsky managed to keep the intuitions that triggered his first works alive? Has he become, instead, an opportunist of the image, a representative of what we could call the “extractivism” of social issues? Can an art committed to prevalent causes be politically deactivated when it enters a circuit of galleries and museums? Is Brodsky, finally, a photographer in his own right, a painter or a conceptual artist?

Jornadas de noviembre. Intervened photography by Marcelo Brodsky

Brodsky’s work evolves and incorporates new struggles, materials, and technologies. And in the last two years, Fernando Bryce has become a crucial road companion for the new aspirations of the Argentine creator. Considered one of today’s most critical Peruvian artists, Bryce has produced since the late 1990s an extensive body of work that draws, like Brodsky’s, on archival images. His ink drawings reproduce in detail magazine covers, posters, advertising, and propaganda designs to construct new ways of representing historical memory.

The affinity between the two, though not technical, is evident at the level of ideas. Moreover, Bryce has also been the focus of some controversy. When in 2012, he presented the exhibition “Drawing Modern History” at the Lima Art Museum, Fernando de Szyszlo dedicated several lapidary criticisms to him. For the modernist painter -whose taste has decisively influenced a sector of Peruvian collecting- Bryce’s practice is not art. The artist has continued to produce a work that seems ready to cannibalize universal history. In his hands, the record of events is transformed into an enigmatic device, where multiple gazes appear ingeniously superimposed -the drawing is an interpretation of the photographic image, which in turn is an interpretation of reality- and where irony tends to creep in among disciplined and meticulous gestures.

Marcelo Brodsky and Fernando Bryce have just shared a residency at Espacio 23 in Miami, where they created the piece Territorios, which denounces the killing of Latin American activists who fight for social justice and the preservation of the environment. Bryce welcomed us to his workshop in Lima, where we were able to connect with Brodsky via Zoom. This conversation records a transitional moment in the work of both artists: a process intensified by the experience of collaborative work.

How did this collaboration come about?

Marcelo: Fernando and I have coincided in several biennials and exhibitions in the last fifteen years. The last one was an exhibition I did at the Henrique Faría Gallery in New York in 2020. Shortly after, Vizcarra was dismissed by the Peruvian Congress, putting Merino in his place, and people took to the streets in the middle of the pandemic. At that time, I was following the National Strike in Colombia. Like Fernando, I have worked mainly with historical materials. Maybe the confinement led me to address the present; I don’t know. Perhaps, it was because I could no longer enjoy the streets and only see them in photos. When I heard about what happened in Peru, I started to talk on the phone with Fernando because he is a very sharp commentator on reality. Then came the murder of Inti Sotelo and Bryan Pintado, and Merino fell. I then decided to do a piece on those demonstrations in Plaza San Martin. I chose five images from different photographers from the Efe Agency, which I rented, and I invited Fernando to work with me. I intervened in the photos, and he made drawings based on the same images, using his way of working.

Jornadas de noviembre. Chinese ink drawing by Fernando Bryce

Jornadas de noviembre. Intervened photography by Marcelo Brodsky

Fernando: For me, Marcelo’s proposal was exciting, not only because we have many interests in common, but also because suddenly this idea catapulted me into the present as well. Working with contemporary images is something I had only experimented with at the beginning of my work, in a particular series, when I was fine-tuning my methods. Since then, I have worked on historical subjects. Addressing the present was an exciting challenge to rethink my work. I was only able to make the drawings this year, and it was in Miami, in residence I shared with Marcelo, that we were finally able to put together the pieces of the Jornadas de noviembre.

How did you go from Jornadas de noviembre to Territorios?

Marcelo: It all started because Jorge Perez, owner of the Espacio 23 collection, stopped by the Met, where my work La Clase is. He wrote to me to see me, but the pandemic arrived, and that was impossible. Then he wrote to me again recently and proposed to do the residency at his place. I accepted, but I proposed a different idea to his team: I wanted to continue working with Fernando. “Fernando Bryce?” they asked me. “Yes, of course.” We arranged to coincide the month of June and arrived with the idea of working in Ukraine.

Fernando: That topic interested us for several reasons. It is a topical issue and a regional conflict with global effects. On the other hand, Marcelo has Ukrainian origins, and I am interested in political history and geopolitics. When we arrived in Miami, we bought books on the history of the war, art, and war, but everything changed there. We spoke Spanish all the time. In the gallery, in the streets, the gallery staff spoke Spanish, and there was a Peruvian restaurant next door. So we said: why don’t we do something about Latin America? Thinking about the relations between Ukraine and our own experience, we started to talk about the dismemberment of territories, the splitting of ideologies, and the crisis of certainties. That word, “dismemberment,” which Marcelo mentioned, brought us the image of Tupac Amaru, which interested us not only as a historical anti-colonial leader in Latin America but as a symbol of a global situation. And then we added to that the issue of the ecological crisis.

Photo: Luis Manjarres

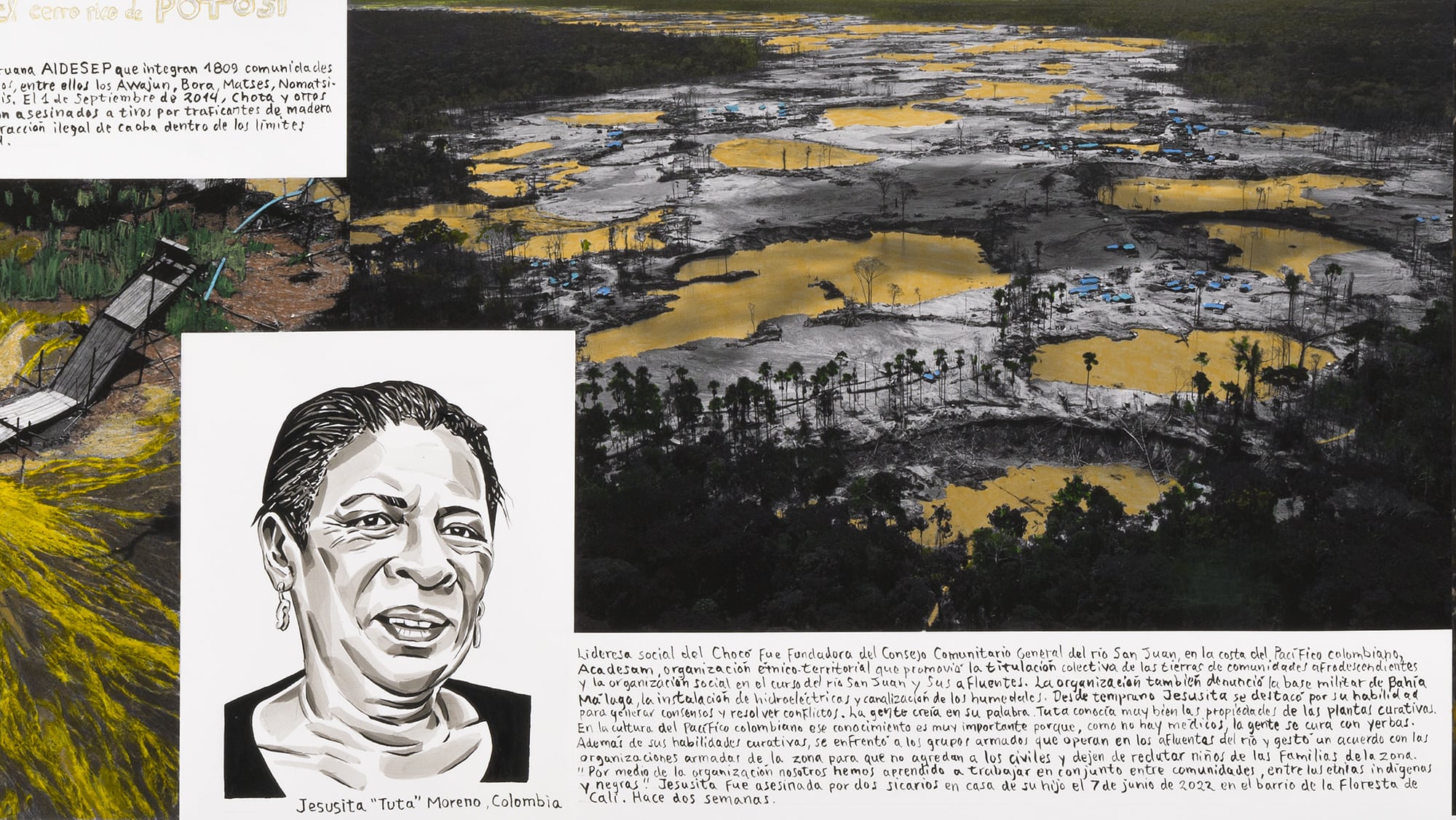

Marcelo Brodsky: “As a result of the murder of Jesusita Moreno -leader of the Choco Region in the Colombian Pacific Coast-, we decided to say something about the killed people for defending nature because they are the full expression of what this struggle costs in Peru, Venezuela, Colombia, and Brazil.”

Marcelo: For the Ukraine project, we contacted an Argentine photographer who was returning from Kyiv, Rodrigo Abd, who works for Associated Press, and is excellent. Then, when we started to investigate ecological issues, Fernando found an impressive photo of the destruction of the Madre de Dios jungle that was also Abd’s. So we asked him to send us other images of the destruction of the Madre de Dios forest. So we asked him to send us other pictures from that area of the devastation from illegal mining and the demolition of the jungle for farming or cattle ranching. The series that Abd sent us combines the usual coverage of the photographer with his camera and the drone. Journalistic photography with a drone is recent, but for a press photographer to go out with his drone is even more recent. We are talking about very modern images. At that time, on June 7, the front page of El País reported that Jesusita Moreno, a leader of the Chocó region in the Colombian Pacific, had been assassinated. Jesusita led an organization that promoted collective land titling for Afro-descendant communities in the San Juan River. It is a region where Afro-Colombians, indigenous peoples, and narco groups cohabit, a disputed area. As a result of their murder, we decided to say something about the killed people for defending nature because they are the full expression of what this struggle costs in Peru, Venezuela, Colombia, and Brazil. So we started to look for other leaders. There are nine countries represented. We have included a historic Brazilian leader, Chico Mendes. A phrase of his appears in the play: “Ecology without social struggle is just gardening.” Another leader is Marielle Franco, a famous heroine from Rio de Janeiro assassinated by criminal gangs linked to Bolsonaro’s son.

Detail of Territorios. Portrait of Jesusita Moreno by Fernando Bryce

Fernando: That was one of the triggers for the play. Another was the word “territories. Then we already had Túpac Amaru, we had the images of ecological devastation – which includes illegal mining, but there is also the Repsol disaster in Peru – we had the idea of social leaders. We began to look for images of the dismemberment of Tupac Amaru. That had to be central.

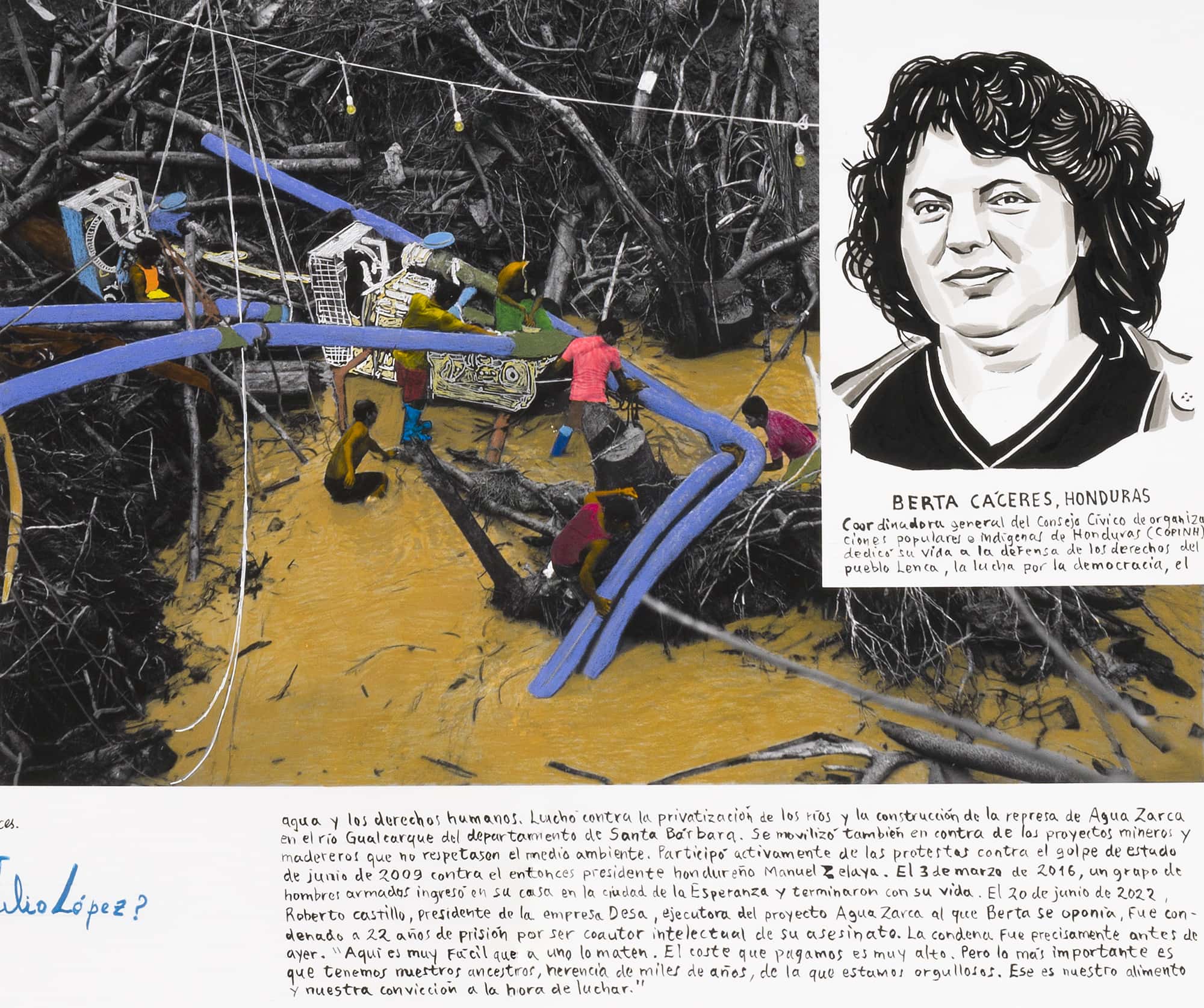

Marcelo: And around that figure, we placed the landscapes. Meanwhile, Fernando was making the first drawing, a pencil tracing of the portraits he would later make with ink and shading. The difficulty was to choose the murdered activists because there were thousands of them. We talked to a friend who runs an organization in Washington called CEJIL, which presents cases of human rights violations in Latin America before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. She came to see us in Miami and helped us. She suggested the names of the Mexican Marisela Escobedo, the Guatemalan Myrna Mack Chang, and the Sandinista commander Hugo Torres, and we completed the set of portraits with her. But also she is Berta Cáceres’s lawyer, who dedicated her life to defending the Lenca people in Honduras, and is displayed in our work.

Fernando: So we expanded the selection to include social leaders defending human rights and victims of state violence. There is the Argentine Jorge Julio López, who was murdered after testifying against a torturer who received a life sentence and died a few days ago. Many of the things we talk about in Territorios have happened very recently. Berta Cáceres is another example: the person directly responsible for her assassination has just been convicted, which is recorded in the text we wrote.

Photo: Luis Manjarres

Detail of Territorios. Portrait of Berta Cáceres by Fernando Bryce

We could say that the work records current events almost in real time.

Marcelo: Exactly. We call it that: art in real time.

Fernando: Jesusita’s text is another example: “Jesusita was murdered by two hitmen in her son’s house, on June 7, 2022”. Practically one day before we started the work.

Marcelo: And then something incredible happened. The Norwegian Human Rights Fund, which financed a project for me in Bergen two months ago, has an office to protect social leaders in Colombia. When the assassination occurred, I called them and asked them to put me in contact with Jesusita’s organization. That’s how we got to talk to the sons. Two days later, the sons call us asking for help to leave Colombia. They were terrified; their mother had just been killed and they did not know where to turn. Here we moved from the construction site to another terrain. We were utterly desperate; we didn’t know what to do to help them. We called the Norwegian organization and Amnesty International, but it was impossible. Finally, I called my friend in Washington, I told her the situation. Within two days, the lawyers contacted the family.

Fernando Bryce: “The question about the aestheticization of violence does not seem very pertinent to me because the facts of history or current events have always been reported with the means available: photography, drawing, painting, or whatever. We cannot invalidate an artistic practice because it use a particular media. ”

Photo: Luis Manjarres

Working with photographs of current events raises suspicions. How to avoid the danger of aestheticizing or beautifying that which documents pain and barbarism?

Fernando: There are very sinister images that I don’t feel like drawing. But there are also images that it is necessary to interpret from art because they have an inescapable symbolic power. Finally, we are narrating. That is an issue that concerns us for ethical reasons. However, the question about the aestheticization of violence does not seem very pertinent to me because the facts of history or current events have always been reported with the means available: photography, drawing, painting, or whatever. We cannot invalidate an artistic practice because it use a particular media. If it is not the suitable medium for what one wanted to say, that’s another thing, but I don’t see that we aestheticize anything. There is an aesthetic, of course, but every plastic manifestation has an aesthetic. Politics also has an aesthetic.

Marcelo: It is an old discussion about the representation of genocide, one of the main discussions in the art of the 20th and 21st centuries. I am referring to the texts by Celan, Foucault, Georges Didi-Huberman on the Holocaust. In Images despite everything, Didi-Huberman talks about three images of the Polish resistance that illustrate the gas chambers. Despite all the discussions on the subject, these images prove something that nothing else proves in the same way. I have just done a paper on a German genocide in Namibia with some brutal photos. Talking about genocide is no joke. The color in that series is softer, and the works are minor, but when you see that, you understand what happened. And there is no other way to tell it because nobody reads it if you write a text. The images allow you to narrate the event, and the technique of intervening the photos with color intensifies the impact and generates an emotional bond with the viewer. That’s what interests me.

Fernando: The image, by its very peculiar nature, so non-literal, creates a different impact than the written text. That is also where the questions come in. Marcelo mentioned an extreme case of testimonial photographs from concentration camps. Still, there are also works made from a much more comfortable situation, by artists who report or reflect on what is happening in the world from their desks. This practice goes back to Goya, who lived through the Napoleonic invasion of Spain from afar, and from his comfortable armchair, he made the drawings we all know. It is a testimony, but not a direct one, that inaugurates a tradition of reflecting on the world and what is happening, which is appropriately modern.

Marcelo: Something similar happens with Picasso’s Guernica. He is talking about the death of his people. We are talking about ours. Because the truth is that Fernando and I are Latin American. Although most of these photos we took in Peru are images that represent Colombia, Mexico, Argentina, and all the countries in the region because people are being killed everywhere.