Early 90’s. Leon, Spain. Night. A child lies down to sleep but cannot. Or he can. The fantastic stories of journeys in distant lands, challenging beings and scenes are his rocking chair and his wakefulness at the same time. Year 2016. Alvaro Laiz is no longer a child. The institution linked to science and photography chooses and proposes him to make it real. This is how The Edge was made body, the photographic coverage that goes back to that place on the map where if the Bering Sea were not, Siberia and Alaska would touch. In his application, Laiz proposed traveling to these lands to follow the footprints of ancestral populations.

His previous works are Future plans, Fosil, Atlantes, Transmongolia, Wonderland, The Hunter. In all of them, the people, their things, their landscapes, non-human persons.

Today he is a National Geographic Storytelling Fellow, and the frontiers of his coverage extended to Tierra del Fuego, as he tells it in this interview. And he has to photograph otherness at a time when we make the ways of enabling looks and voices more complex, we think: how do we represent others, what is the meaning, where is the limit.

Your work The Hunter has a photographic tour, also on video. You used different languages to tell a story based on a legend and in a specific case at the same time. How was that process?

It completely changed my understanding of photography and the power of visual storytelling. Without The Hunter it would never have been possible for me to make The Edge.

When I learned about Vladimir Markov’s case, I couldn’t believe it. Those are things that no longer exist in our world. We are so immersed in the city and in our technological world that the story of a Siberian tiger that chases and hunts the man who tried to kill him sounds almost like another world… It was the opportunity to delve into the territory of the classic archetypes of the man in/against nature: Captain Ahab, Dersu Uzala.

I proposed the project to Fundación Cerezales. Its support was a springboard, it allowed me to make the leap from documentaries more attached to reality to a more authorial tone and, perhaps, freer.

You were able to play and build a story. How did you get to that story?

The story fell into my hands thanks to John Vaillant, author of El Tigre, a book that has been very successful worldwide. I started by contacting local authorities in Primorski, natural parks, etc… from there the production work began. The project consists of two long trips to the Prirmosky Kraj, in autumn and winter, during the hunting season.

Two stories are mixed in the project: that of Markov the hunter, and my own experience with the Udegei hunters. I was very interested, for example, that these apparently folklore legends have a very strong pragmatic base, especially in the case of the tiger.

Those are stories that serve to survive, like all stories. In the Southern Cone, for example, spirituality, legends and myths are not far from survival, they have a practical sense.

That’s why I got closer to the hunter culture. It is one of the last remnants of animism in Russia. There, during the Soviet times, shamans and everything that had to do with spirituality were harshly retaliated. Hunting, being an individual and highly specialized activity, has kept alive a series of traditional reading and interpretation practices of the Arctic taiga. It is an extremely tough site. The Boreal Jungle is a closed forest environment with temperatures below 40 degrees below zero in winter and above 40 degrees in summer.

However, the Udegei hunters’ relationship with the intangible or spiritual is highly poetic. There is hardness and delicacy at the same time. It is a paradox that the Siberian tiger exemplifies very well. An animal of more than 350 kilos of pure muscle capable of appearing and disappearing like a ghost in the taiga. Part of the challenge when tackling the book was getting these two facets together. And in that sense I’m proud of the result because I think The Hunt balances them pretty well.

You said that this work changed your bond with photography.

It changed because it also allowed me to play with the exhibition space. The project had three forms of expression: an exhibition, a book and a multimedia. They all functioned on a different level, with different nuances.

On the one hand, the story had a super clear narrative part: beginning, middle, ending. A hunter tries to hunt the tiger, but only manages to wound it and escapes. The Tiger returns transformed into an avenging spirit and the hunter becomes the prey… I think it was during the conceptualization and production of the photobook that we really delved into the spirit of the story.

Probably if I started today the same project there would be many things that I would do differently, but I think that the decisions we made when putting together the book would remain the same.

Your previous projects, such as the one in Venezuela or Mongolia, were made in a traditional language, that of the photo report.

Yes, I agree. I come from journalism, but my connection to anthropology and ethnography has been through my photographer work. In Mongolia I started working from a more classical point of view until I decided to try new things, because I felt that what I was doing was not working. That change came about thanks to the relationship we established with the trans community in Ulaanbataar. In many ways it was a first experience: with auteur documentary far from the rules of classical photojournalism and with the themes that would later mark my subsequent works, such as identity or animist cultures.

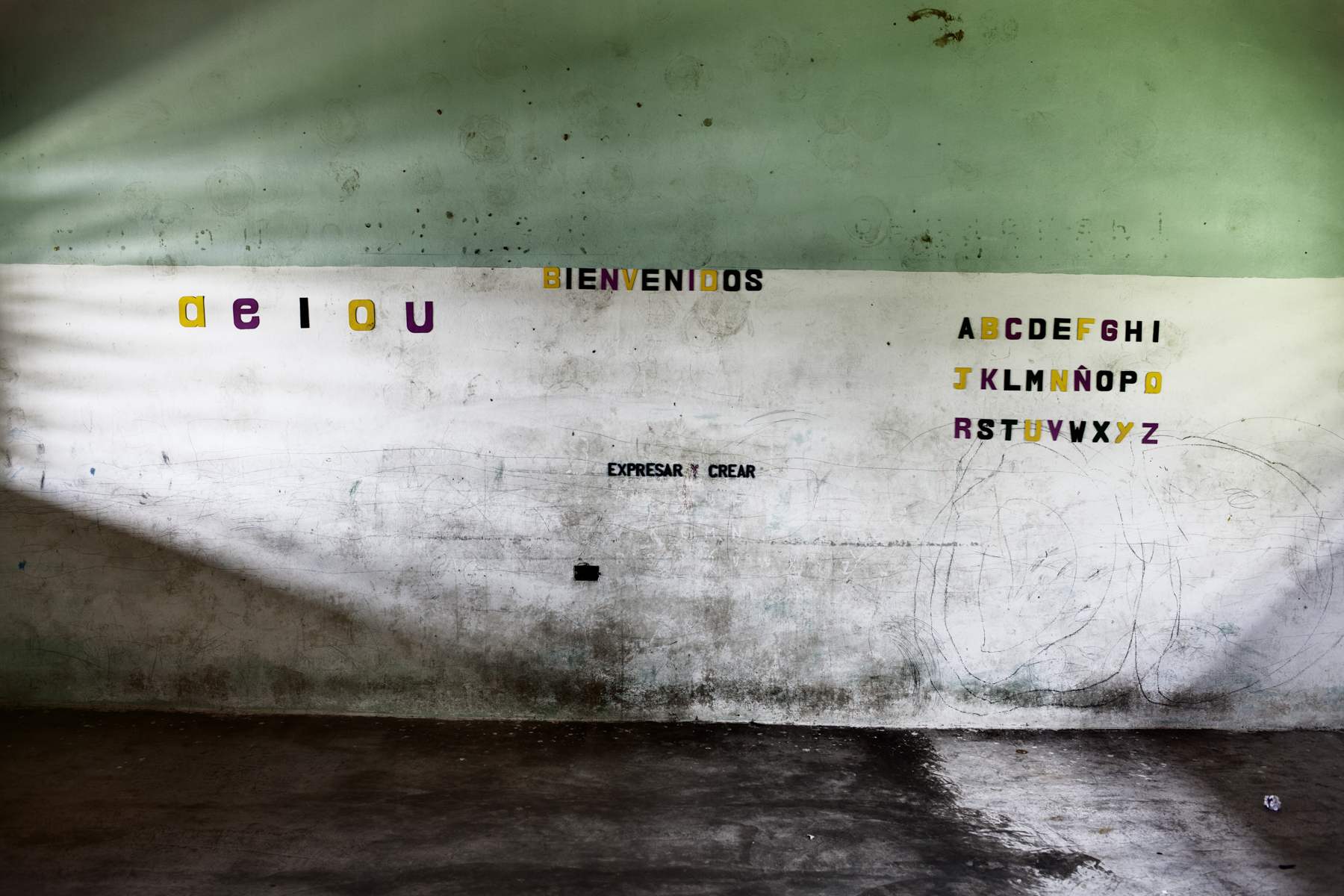

In certain places, particularly in northern parts of Russia, Mongolia and America, transgender people are considered as portals to divinity, shamans. I did Transmongolian in 2009/2010. Two years later, an anthropologist who had seen my work invited me to Venezuela, where there is a similar context regarding the trans community.

After Wonderland I began to perceive the relationship between nature and culture differently. There I became interested in shamanism and traditional cultures, and I began to include the environment as one more character in the series.

In The Edge you definitely take your own path.

Yes, let’s say it was the confirmation that my head works going to the limit. That is to say, to the limit of what I know, of what I know how to do. And that is something tremendously exciting but also very scary. The project was born thanks to an explorer grant from National Geographic, and with the pressure to replicate a little what had gone well in The Hunter, but in an even harsher environment: in Chukotka in the Bering Strait. Everything that can go wrong does go wrong, my plans were blown up as soon as I got there and I had to redo the project on the fly.

My first experience in Chukotka was very complex from the first moment. To the logistical difficulties (two planes, a helicopter, snowmobiles and to finish a dog sled) are added the bureaucratic ones. It is a militarized area, due to its proximity to Alaska and you cannot move on your own. You need a lot of permissions. It is a complex area and it can be difficult to know exactly what is happening if you do not have a lot of experience in the region.

When I arrived, the fixer I had gotten decided I wasn’t going to fulfill the part of it and disappeared. I had to drive myself alone in an area where my hands were practically tied because every 5 days you have to report to the authorities. But thanks to that I reconsidered many things and I met people who opened their doors to me and the possibility of doing something completely different from what I had planned.

I opened my eyes to what I was finding. Thanks to the chance and the hospitality of wonderful people like Galina Kanchugá, an English teacher from Krasni Yar (the same village where I did The Hunter), I discovered that Chukotka was more than reindeer herders and whale hunters: it was the nexus of union between Eurasia and the American continent. Scientific studies of population genetics in that region have found that the Chukchi people share a common ancestor with most of the native tribes of the New World. That’s the end of the thread that I started to pull. A cross between science and storytelling. Interesting, right?

Was the discovery of population genetics in the field or did you already have that information?

I’ve always been very curious about this particular topic; in fact, over time I ended up doing the ancestry test myself. One of the advantages of working with National Geographic is that the institution connects you with photographers, editors and journalists but also with scientists, anthropologists and ethnographers. People from very diverse disciplines with a common interest. Better understand the universe in which we live.

The Genographic Project was born with the objective of mapping the journey of the human being from our origins in Africa to the present day. Where we come from? Who are our ancestors and what is our lineage? For me it was an advantage because during my work in Chukotka, especially from the second trip, I was able to involve people from the community through this project.

I was used to working with stories from the narrative, but in this case I was faced with a completely new methodology, so it was a challenge. There is a lot of scientific literature on the subject, on how the American continent has been populated, on how migrations have happened. But obviously there is nothing visual, there is no image, there was no one on the other side when a group of hunters crossed the Bering Strait for the first time 20,000 years ago… but we are left with the footprint, the data, their echoes over time… Their descendants remain.

As the project began, one of the references that came to mind was In the American West, Avedon’s great work, in which he portrays the United States from within. However, to this day he has taken slightly different paths and is still in a process of change and evolution.

How does this project and your way of photography evolve?

At first it was limited to the Bering Strait, now it covers the entire American continent. These last three years I have been working in the United States, in the regions of New Mexico, Utah and Arizona and in Mexico in Oaxaca. It remains part of Mexico, Peru, Chile and Tierra del Fuego Argentina. With time, travels and readings have made the core of the project have a greater impact on our condition as a migrant species. We are a curious species that seems doomed to tirelessly walk towards new horizons.

My point of view as a narrator could no longer tend towards the particular but rather towards the search for the supra-individual; a broader perspective of the human being as a species. This implies talking about identity from a different place and understanding our relationship with and in time in a different way. This change has a lot to do with the thinking that I have encountered throughout the journey from Russia, the USA and Latin America: claiming your roots and at the same time projecting yourself into the future.

Thinking long-term, right now, is almost a forced survival exercise for our species. Climate change, our relationship with the environment, with our elders, with cities, with technology… all of this is ceasing to work for us. We cannot think that we are the last generation to inhabit the planet because we are not. On the contrary, we are enjoying advantages and certain conditions thanks to previous generations. Placing ourselves within a larger time scale and (perhaps) promoting a change in that short-term mentality is one of the axes of this project.

” I immediately connected with that way of understanding one’s identity as a sum of past identities. I needed to reflect that multidimensionality in a graphic way.”

Thinking in different planes of time also has to do with the objects and culture with which we interact. How is this reflected in your photos?

In relation to this, I am going to tell you an anecdote about how the Chukchi name newborns in Vankarem, which is a small village located well above the polar circle. They have a very strong bond with the past and that bond is reinforced in rituals like this one. The newborn undergoes a process in which it is given a name according to the ancestors that inhabit it, because according to the Chukchi cosmogony each one of us carries the spirit of all our ancestors: we are them. I immediately connected with that way of understanding one’s identity as a sum of past identities. I needed to reflect that multidimensionality in a graphic way. On the one hand it means playing with time and on the other with space through my camera.

One of the most beautiful things about this work is being able to dedicate a lot of time to being present in each place. From my second trip to the Bering Strait, I dedicated myself to being with people, entering their houses, saying hello and smiling. To listen. I took away the anxiety when shooting, I started to think.

Did discovering how to get names also mobilized your way of taking portraits?

Totally. Each place, each part of this trip has brought me new questions that I try to answer. I started a series of photographs from a more documentary record. That completely changed in Chukotka. I realized that what I wanted to tell was no longer just about the Chukchi people but that I needed a way to structure the project from north to south across the American continent in completely different circumstances and environments. I found in those concepts of identity or axes between past, present and future, the bases on which begin to build.

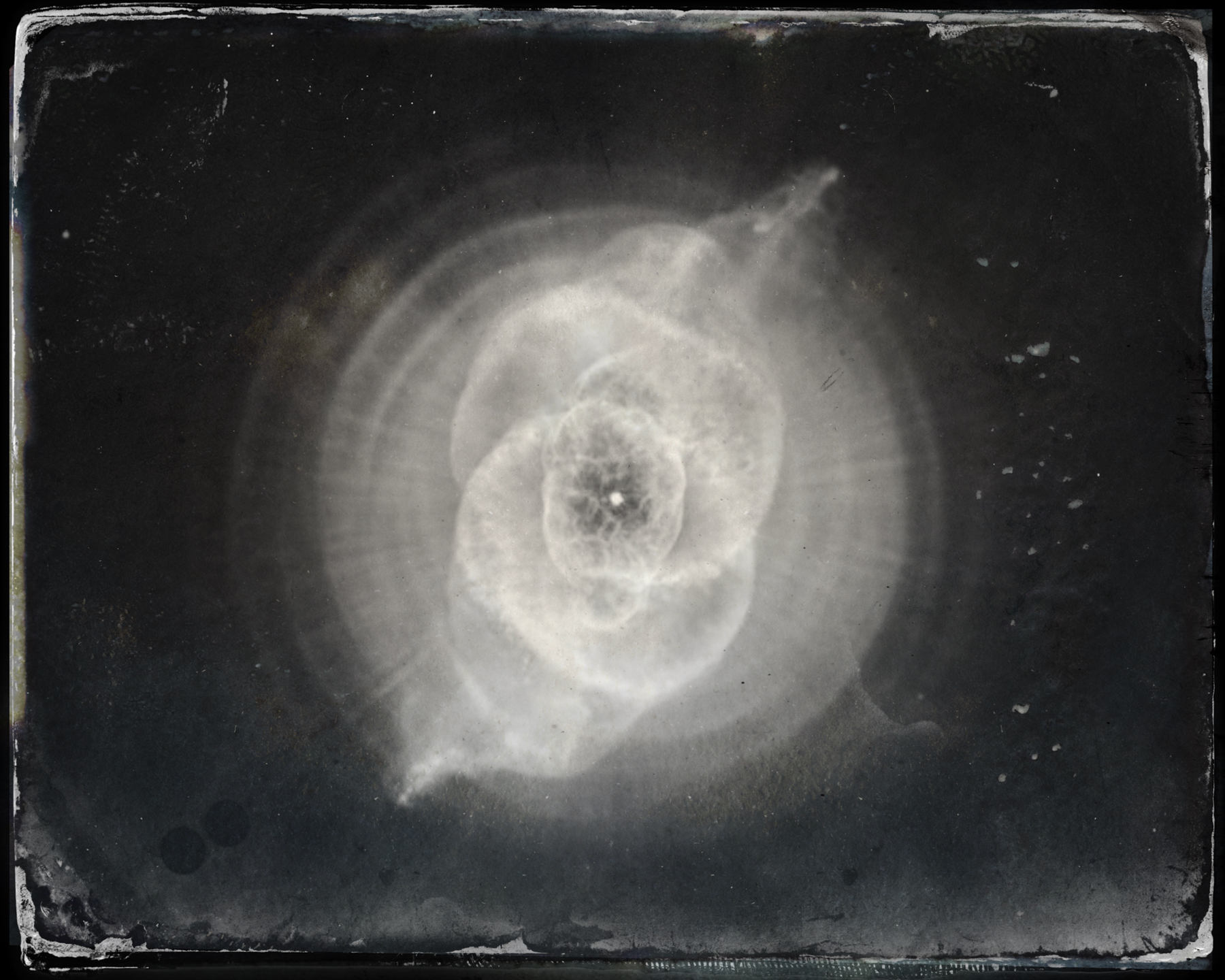

In the United States, while working together with the Navajo community in the Navajo Nation, I realized that in order to understand and put these migratory events in context I needed to show when it had happened, to place myself in what is called Deep Time, the geological time that is measured in thousands of years. That’s where the constellation series was born.

Photography of the sky is always photography of the past.

Yes, the different dimensions of time and how we perceive it are very present in the project. There is another part of the facility where I work on visualizing the genetic data collected from the project participants, which in the background is a map that allows us to locate ourselves in our history.

It has two parts: sound and visual. The visual one is related to a certain type of ritual dance. I am interested in this part in which knowledge requires the invention of a language to preserve and share it. Ritual dance contributes precisely that. A code that transmits a message from generation to generation in a very archaic way, through gesture. Knowledge that needs to be decoded to be fully understood.

I believe that the parts related to scientific knowledge and empirical knowledge of the project represent two sides of the same coin.

And it’s hard to do it. In words it is impossible. How to show it in images?

I think that when I think about it there is a part of my head that associates these ideas with cave paintings, with a certain kind of schematic knowledge, very simple and elemental but at the same time very deep. What I am looking for is not so much that the viewer wonders how the piece is built, but about the place to which it refers. It is a bit like the idea of the cave, the uterus, the origin… The part of the sound installation processes the different DNA sequences into vibrations, for example. It is something as subjective as that.

The ultimate goal isn’t related only with obtaining an image, an object or a sound, but with finding other ways of transmitting or decoding knowledge and data. Transform them into a sensory experience. Somehow, to invent a language that adapts to the needs of the message.

You went from working as a reporter for the Metro newspaper to these projects. What is your quest? What motivates you as a person to move to these confines and to look for things in detail?

I don’t know. Each of these projects has been a step into the unknown. The Edge is helping me grow both personally and professionally. I begin to understand many things about myself through photography, the world of art and this freedom that I am allowing myself to take. I think that when you dedicate yourself to our trade it is because you cannot avoid it.

Part of that fascination for other worlds that you have from when you are little, when you see the world through literature and movies becomes the urge to be part of them in adulthood. At the same time, there is an intuitive, almost spiritual connection with the places and stories that I choose that contrasts with my more analytical side.

I think it is largely the friction between those two parts that has made me take certain paths and not others.

Science and poetry again. But inside you.

I believe that the challenges that each of these places have posed to me have made me more aware of the decisions I make and have forced me to change. I am not the same person as in 2009, 2012 or 2015 in many respects. Years ago when I listened to photographers and artists talking about how they lived photography, I did not understand.

I think it’s something that happens to all of us when the time comes. The way of looking, of relating to the world is what defines your life experience. The Edge has forced me to ask myself many questions that in many cases are contradictory. That is something you cannot rush into.

Fortunately, thanks to the support of institutions such as National Geographic or the Museum of the University of Navarra, I have been able and I can dedicate the time that I need, something that at the moment is, sadly, a luxury.

” I particularly believe that our future as a species passes through the intersection between scientific thought and indigenous knowledge. Feet on the ground and eyes on heaven.”

We are at a time when jobs like yours become complex. Today we question the other’s gaze. What is the legitimacy of the other to address certain issues? What does that look represent? Are the forms of approach changing? How do you get this dichotomy?

I have thought about that a lot, especially as a result of the collaboration with MUNAV (Museo Universidad Navarra). Tender Puentes is an artistic residency that asks for a dialogue with its collection of photos. Authors like Napper, Clifford or even Ortiz Echagüe have a very specific approach, with a typical point of view of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, about what the other is. This type of approach, which today would be conflicting, has offered me the opportunity to rethink many questions about my responsibility as a storyteller.

I think that many minority groups have been the object of a stereotypical representation, of the search for exoticism or directly of the lack of empathy on the part of documentary filmmakers, artists and scientists. Fortunately, these power dynamics, although very gradually, are changing through, among other agents, native artists and scientists capable of narrating, not only their own stories, but also contributing their point of view and value systems to a global scale.

In my case, that requires me to question who I am, what are my frames of knowledge, how they affect my perspective and from where I position myself as a storyteller. In this project I have tried to abandon the documentary and have embraced the most subjective part of my work, seeking to get as far away as possible from a stereotypical representation. Get closer to a much more global concept.

I believe that the stories, the myths that we tell ourselves have immense power when it comes to shaping our reality. Questioning and analyzing them is a way to prevent them from possessing us, to lose our footing. And the only way to get rid of them too.

I believe that we are in a historical moment in which the myths of the industrial revolution are reaching the end of their life cycle. They are simply not sustainable. The myth of perpetual growth, for example. That is why it is more important than ever to listen to voices from the periphery, far from classical dogmas. I particularly believe that our future as a species passes through the intersection between scientific thought and indigenous knowledge. Feet on the ground and eyes on heaven.