In 2016, the Spanish photographer Arguiñe Escandón found an old postcard of the Amazon in the Madrid market of El Rastro. It was a colorized photo, taken in 1888 near the Ucayali River in Peru. It showed a group of people posing in front of a huge crocodile. In the center, a white man with a rifle in hand, surrounded by a dozen indigenous people from the area. The scene summed up a kind of South American safari: the commonplace of the white man visiting a territory that in his eyes was exotic, surprising.

Arguiñe decided to mail it to her colleague, the Swiss photographer Yann Gross, who worked in the area. She accompanied it with a message: “Be careful in the jungle, remember to blow three times so that the trees give you their permission. Protect your right side well, do not end up like the protagonist of this photo”. She was referring to the German Jean-Jacques, known as “Charles” Kroehle. The man had traveled South America in the late nineteenth century until he died, from an arrow wound that he could not heal in time. His photographs were key to the creation of the imaginary that exists to this day of the Amazonian universe and that Yann and Arguiñe wanted to retrace. For that they decided to go after Kroehle’s footsteps and traveled the same path but with a sensory approach, trying not to repeat “the Amazonian clichés.”

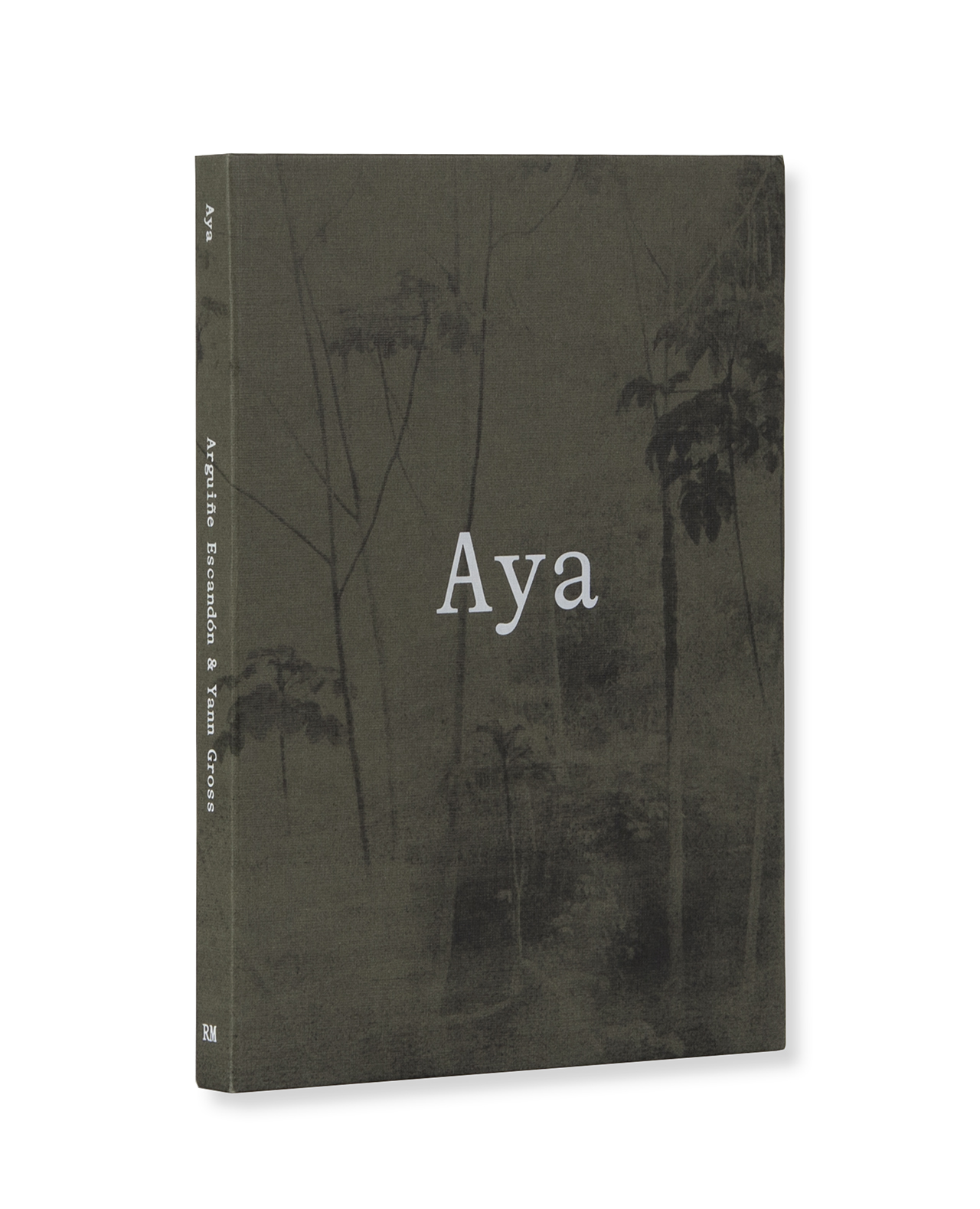

Several trips later Aya was born, published by the Editorial RM and was nominated as one of the best books of 2020 in several relevant selections, in it they combine old images with others of their own. The question that runs through the work is how to transcend the colonialist approach that prevailed in Kroehle’s photos and that, the authors say, continues today by other means, transformed into its reverse: a romanticized and melancholic image, which longs for a supposed lost paradise or , hopefully, about to be lost.

Both work without eluding their own place of origin: the two are others that enter a foreign territory, a position that encourages doubling the questions and the care when constructing a story. This contradiction is resolved –or muffled– when they put the body.

In one of the texts in the book, the son of a shaman tells them:

«If you want to learn about plants, you have to prepare your body. Each plant has its own spirit and personality. They can talk to you. When you eat them, they will be your teachers. They will draw your emotions from within. They will teach you how to reconnect the body with the mind… »

The teaching resulted in each trip becoming a diet: a series of ceremonies that sometimes last weeks, in which it is possible to bond with each of the plants and let them speak from within the body.

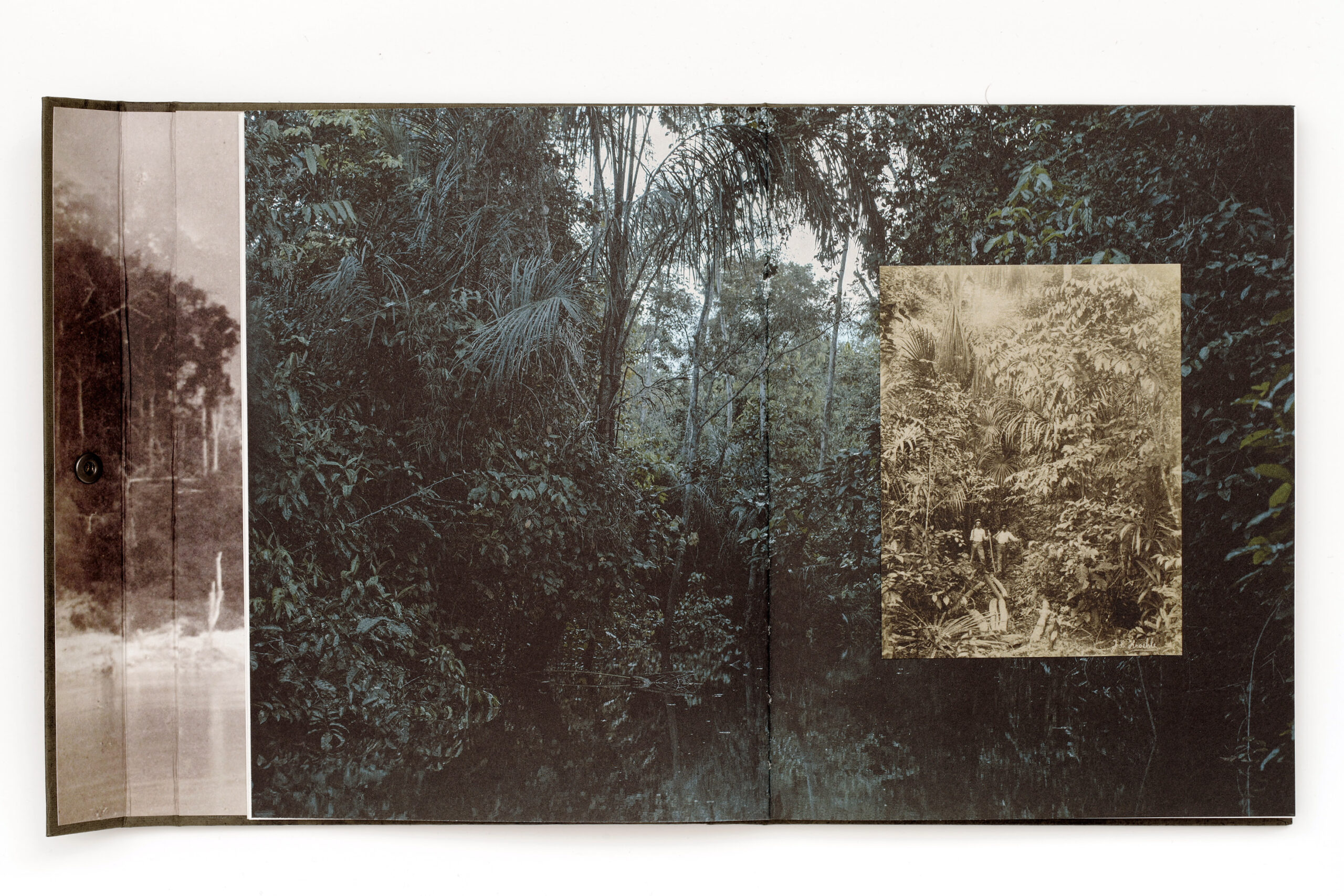

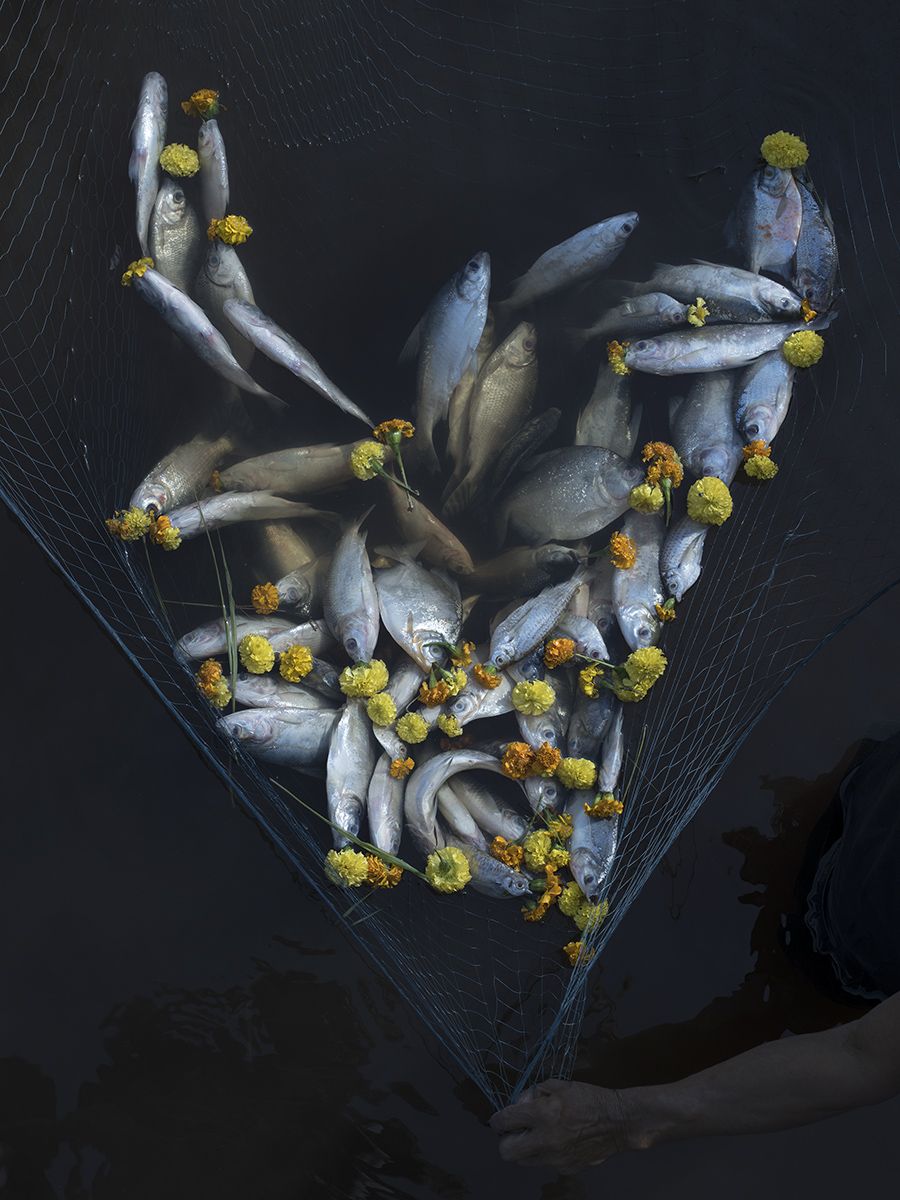

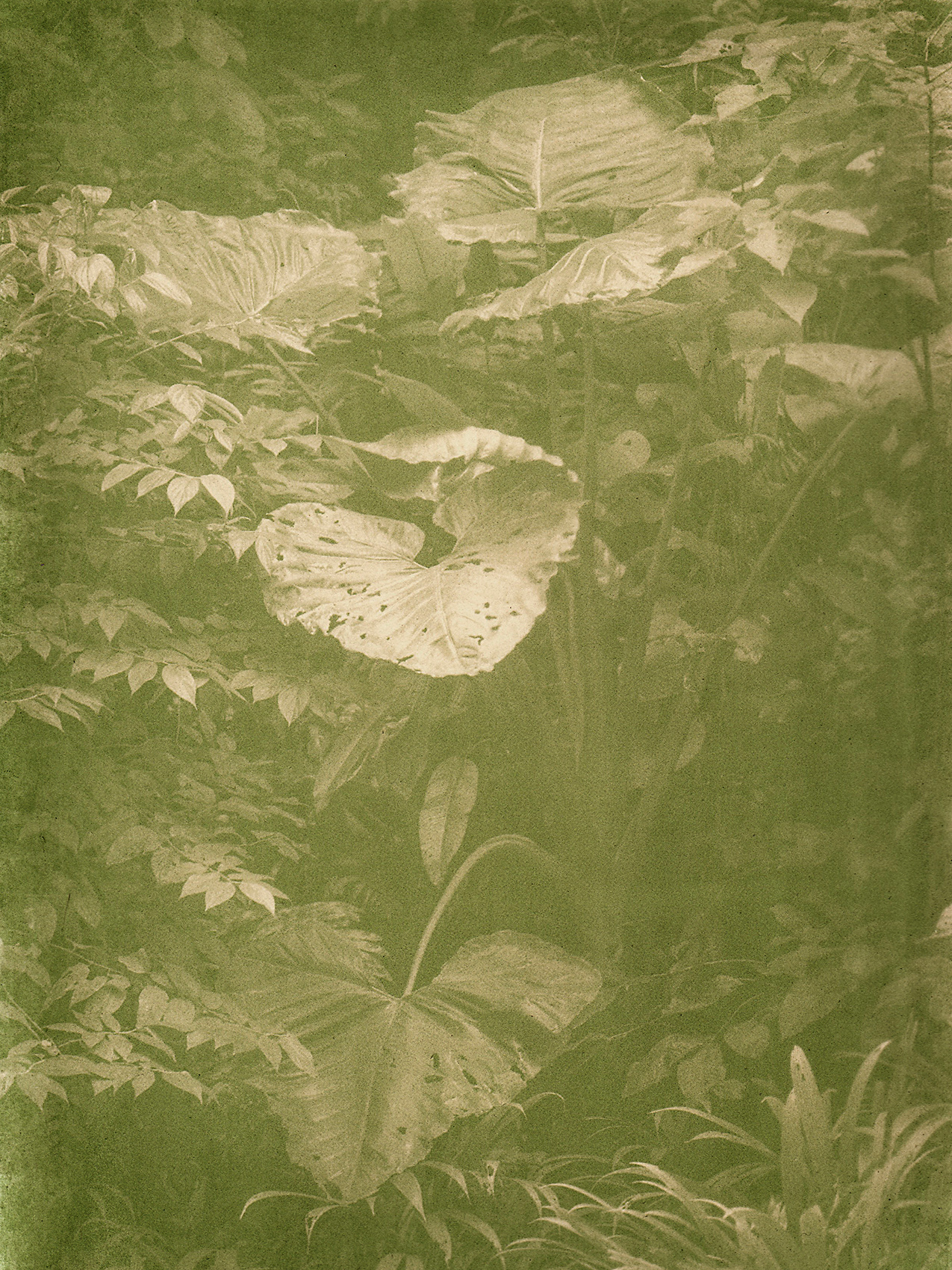

On this path they learned that “the best possible way to represent the jungle was for the jungle to reveal itself.” So they looked for plants with photosensitive properties, set up a laboratory in the middle of the forest to experiment with different botanical development techniques, and used semi-transparent snakeskin to create a photogram. The result is reflected in a book that represents the jungle in a deep and complex way. For Yann, in the photographs –and in the jungle– there is poetry to the same extent as darkness and fear.

If geographically they make the same journey as that photographer of the exotic, so as not to follow their destiny –those danger that the postcard with which the project began– warned them with their travels and with each diet, they enter the deep duality of the jungle and pay the tribute that the forest asks for those who want to know its secret: to put their own body at stake. In other words: that powerful and overwhelming duality that lives in the Amazon can be eaten –perhaps never learned– only at the cost of leaving the postcard and letting yourself be trapped by the jungle. What is on the other side is that duality that also lives within us, but that few dare to dive.

How did the relationship with Amazon begin?

Y: I have been working in Amazon since 2008 for the project related to The jungle book. And in 2016, when we started working together, we decided to change the creation process to make this new book in a different and shared way between the two of us.

A: he was working in that field and he already knew it a lot. We were interested in doing it together in a way that showed that we were four hands, two people. That it wasn’t like a continuation of the path he was already exploring. It all started with a postcard. Yann and I have known each other since 2008, when we were both nominated for PhotoEspaña Discoveries. There we met and became friends. From there, we kept in touch, knowing a little what each of us was doing. I discovered one day at the El Rastro market in Madrid, a postcard that would later become the first page of our book. I sent that postcard and from that moment on a search begins, an investigation.

Y: I was quite familiar with the anthropological studies of the Amazon and its graphic representations. This postcard caught my attention because I did not know about the existence of this photographer.

We discovered that there was a fairly unknown story about Kroehle’s photographic work in the Amazon. We think it would be nice to continue an investigation together, taking this image as a starting point for a new project.

If you had to explain the book, what would you say?

Y: on the one hand, there are the discoveries from the archives of this photographer. On the other, our way of photographing while we progressed with the investigations. And behind it all is the experimental part with plant juice. In all these things there is a common thread. Knowing the steps that this photographer had taken, the idea was not only to keep track of him, but also to try to teach our experience of the jungle.

We don’t see it as a documentary project, because Kroehle’s stance was quite… How can I say? On the one hand, he was the first photographer to do consistent work in the Peruvian Amazon. But he is also quite connected with a colonialist look at the rubber extraction era. There are a bit of those two faces. We, as European photographers also going to the jungle, in the end we were asking ourselves: what is our goal? What is our role? We can repeat what has been done over the last centuries or we can tell it in a different way, guided by our own intuitions and experiences.

A: In a way, it’s a much more sensorial work for us. We go into the jungle but we talk much more about emotions or sensations. What is it like to be in something that somehow comes out of the parameters of the human being, which is much more immense than ourselves. We seek to separate ourselves from that vision of ourselves as human beings, but everything else that, in the end, is container and contains.

Y: living with one of these indigenous communities, at one point, they told us that if we really wanted to understand the jungle, then we should talk to it, we had to diet its plants. And there we could begin to converse with their «spirits». To this is added that when you are in the jungle you also lose a little of your technological and cultural references. We took advantage of those moments to try to photograph and see where the state of mind we were in was taking us a bit. The conclusion was that perhaps the best possible way to represent the jungle was for the jungle to reveal itself.

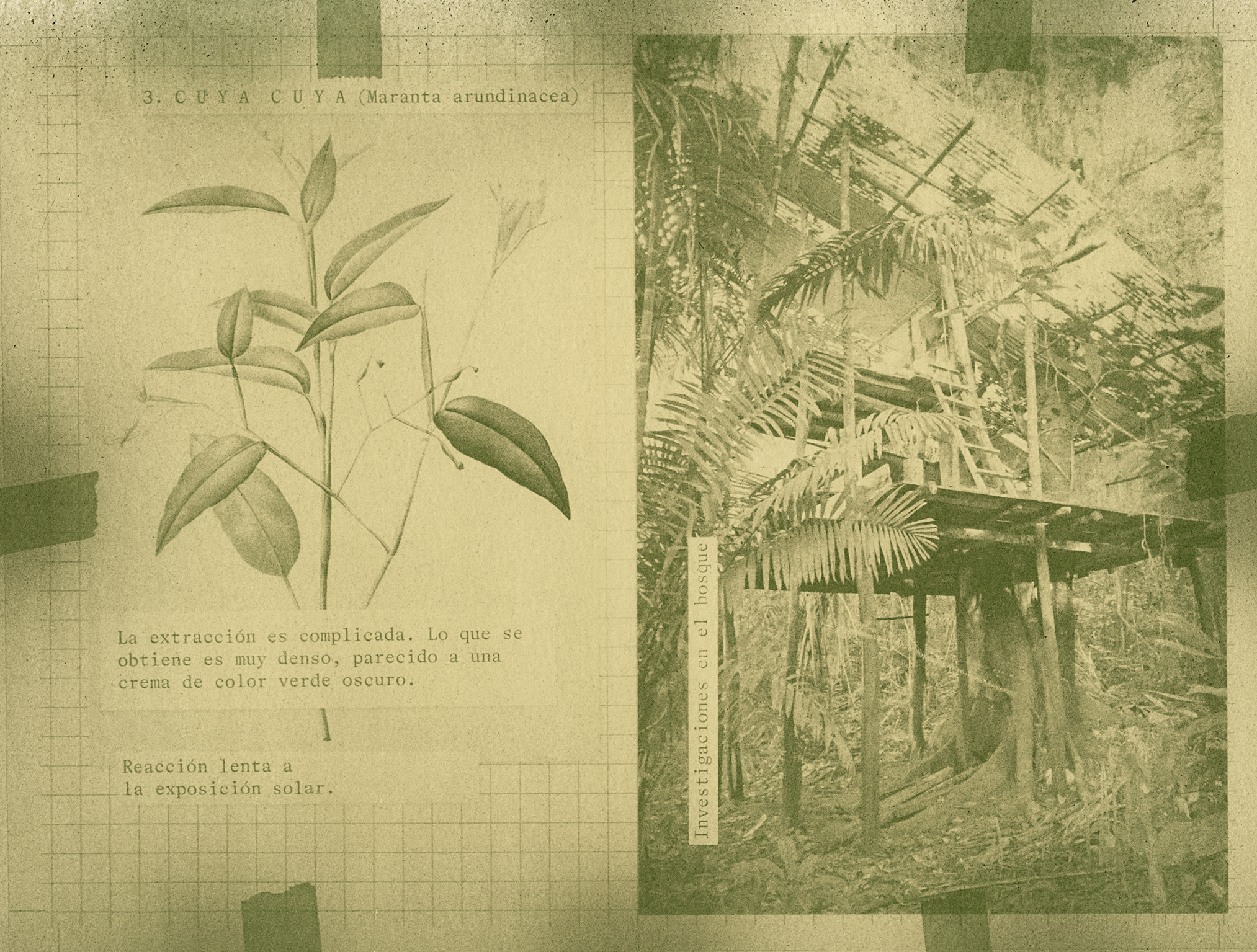

We began to identify plants that had photosensitive properties, with which we could then represent the forest by collecting the leaves of these same plants.

“On each trip, we were on a strict diet of a different plant.”

How did you trace the route of the trip?

Y: as a starting point we chose to travel the Kroehle route through an album of photos by him that we found in Paris. This initial route was modified as experience itself revealed new directions. For this project, we were in the jungle for a total of seven months on various trips that lasted between six weeks and two months. On each trip, we were on a strict diet of a different plant. Then we would go out for a while to process everything we had already done before going back. We started in the Ucayali region, going down to Loreto, Iquitos and then we went up to Tarapoto.

What was that moment like when they told you “to be able to dialogue with the jungle and get away from that colonialist look with which this photographer came, you have to do the diet”?

A: He was the son of a Shaman, Mario. He was our first contact to start experiencing plants. In the book there is a «Manual de convivencia en el bosque (según Mario F.)» and they are the exact transcriptions of what he told us about each one of them. He is an essential person in the development of our project. Since through the knowledge of him and the closeness of him a very close bond was created that gave us security and confidence in each step.

Sometimes we have an idealized version about the jungle. In thyour is work it is transmitted that the jungle is not necessarily an idyllic place …

Y: the interesting thing is that the representation of the Amazon has not changed over the last century: the imaginary we have is the same as we had 120 years ago. Before, when discovering these peoples, the images were to show what the savages, the un-civilized, were like. Then this changed and those same images today are seen as romantic images from a past that we have forgotten.

There is this idea in industrialized countries that the Amazon is still a virgin sanctuary. We, as photographers, set out to convey those sensations that the jungle gave us without reproducing overly romantic images.

Because, you know, in the jungle life is quite hard, it is not so idyllic. For this reason, in our photos there is poetry but there is also a whole part that is a bit scary, which is dark. If you look at our photos they are taken at the end of the day or at dawn, when that light is there …

“it is convenient to make a little parenthesis: the word “photography” has been used for the first time in Brazil. It was Hercules Florence.”

How was that job of developing the photos with the plants?

Y: we have developed that with the people there. We knew that sometimes you could take a photo from a leaf. We thought that maybe there was a way to use the liquid alone: if we can extract the chlorophyll, it could have a somewhat interesting reaction.

We started these investigations with various medicinal plants known by the communities. We apply our emulsion on a llanchama, a cloth made with the bark of the tree. To see if there was a possibility of obtaining a gradient pattern, we used a snakeskin that lets light through at different intensities. So we did organic frames first. Then we applied this technique, with images of the landscapes in which we were going to collect the plants that will be used for printing.

With this, it is convenient to make a little parenthesis: the word “photography” has been used for the first time in Brazil. It was Hercules Florence. He had developed a process very similar to what was later called a daguerreotype five years earlier in the São Paulo region. The interesting thing is that he says that before having made all his discoveries, he had traveled three years through the Amazon to research and draw. There he had noticed the chemical action of light on the different colors present in nature. Therefore, it is likely that photosensitive reactions in the jungle have been known in the Amazon for a long time.

A: We both had the feeling that, in the end, the story just depends on who tells it to you. We really wanted to go into saying “well, there are other references that maybe we haven’t even explored before.” When the history of photography is studied they speak of “so and so and so” from a more European perspective. But this man developed this five years earlier in Brazil. All this led us to want to get closer to the jungle and set up a laboratory within the jungle itself.

Personally, did doing this project change you?

A: yes, starting with the disconnection you feel: suddenly there are no telephones, or anything that allows you to communicate with your everyday reality. That immensity makes me feel very small in a very positive way. When you are there in some way it is like everything stops and something much more sensory appears. The senses are more awake, while in our day to day, sometimes, we do not take the time to stop to reflect. As if we were driving on a fixed road where we looped countless times.

Y: there is a reason why I always return to the jungle: it is that sometimes it allows you to get out of an intense rhythm. It allows you to observe the world in detail and in a less self-centered way. When you are connected, you get a lot of news about what is happening in the United States, in China or I don’t know where. These sometimes distant things can affect you even when they have no consequences in your life. In the end you can forget the most sensory part and focus on what is around you.