Toni Amengual defines himself as an artist, photographer and visual educator. In his biography, he says that he dedicates his life “to the study of the most complex species on the planet and to which I belong: Homo sapiens sapiens.” He uses photography as a tool to investigate people’s ties to the world. Before that he worked as a reporter for the principal Spanish newspapers. But it was his curiosity as a “builder of books” that ended up revealing his genetic mixture: the aesthetic search in symbiosis with the theses of biology, a career in which he graduated following the inheritance of his scientist father.

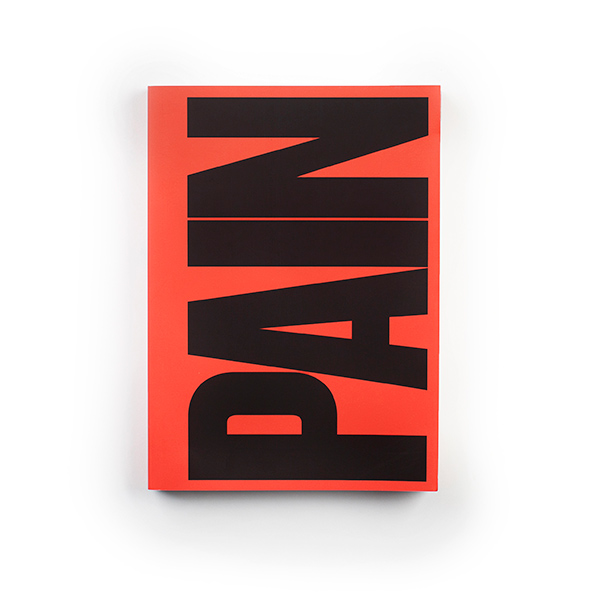

He was born in 1980, he is from Mallorca and he lives next to the sea. The trilogy of photobooks made up of PAIN (2014), Devotos (2015) and Flowers for Franco (2019) took him far: to the MOMA’s permanent collection, to the Time Magazine ranking for his contribution to collective history. For Amengual, recovering and renewing stories about memory has as much to do with revisiting the sites of the Spanish Civil War as the symbols of the emptying of heritage generated by the tourism industry. His gaze, without his vanishing point, now leads him to Rome, where he will go on a scholarship to carry out a new essay. Toni thinks, takes photos, shares them: it is not social rebellion, he says, it is a need for self-knowledge.

You are always breaking boundaries. In 2010 you were already taking photos with your cell phone to post on Facebook.

I seek to experiment and do different things. I have a drive to constantly try new things. What I already know and know how to do bores me. Then I stop to think and feel that what I have done must make some sense. In this phase I try to order what has been done and make sense of it at a project level. I like to seek the limits of photography. Hybridization seems to me to be one of the best ways to do this. Photography, understood in a classical way, seems to me a conservative and boring field. I really appreciate the great documentary works of the mid-twentieth century, but I understand photography as something alive. As a scientific discipline that evolves and seeks solutions adapted to its time. Perhaps that idea of photography as a science comes to me from my studies in Biology and from having a medical father who at 71 years of age continues to evolve and work more than ever.

Your work has a very personal stamp. It is anything but closed, archaic or conservative.

I studied biology and photography. I was interested in leading a way of life outside of routine and authority. I don’t get along with imposed routines. I dreamed of being able to travel, see the world, meet different people and places and have an interesting life. I think that for now, with effort I am getting it. I have not achieved it through a print media, as my initial idea was. I quickly abandoned the idea of photojournalism because it seemed to me that it was a very constrained language on an expressive level.

I noticed that what interested me about photography was its ability to tell stories and at the same time the possibility of approaching them on a personal level. I like to do documentary work but with a strong author’s vision. I also like to use the humor code, even if it’s black. In the world of creation, it is assumed that artists use photography; I like to think that I am a photographer who uses art.

How did you get there?

It was involuntary. My initial idea was to work at a photojournalistic level, but I quickly realized that my work does not fit into those circuits. But my work began to gain acceptance in more artistic circuits: exhibitions, festivals, museums.

Which do you think is the role of photographers who use art, what would be the circuit for these productions? The media is no longer the place to publish deeper visual productions. We are in a kind of limbo, and you have tried to work and market your projects from social networks.

The outlook is complicated. I defend the image and photography, the visual story as a generator of awareness and opinion. I always put the same example: if it were not like that, advertising would not use it, and it is their number one weapon. We can discuss why the media no longer value it, I think they would be super interesting platforms if they were renewed and connected with the new ways of working that we, a new generation of photographers and documentary photographers, have developed. I suspect that the problem is that those who run the newsrooms are far from this generation and even further from those to come.

The world of art is also a complicated world because those are complex and difficult issues. The refuge of my livelihood is teaching, it seems to me a place where you can work a lot. Institutions should also take that over; I’m talking about festivals, museums and public spaces whose function is to make a visual pedagogy and talk about issues that can be socially uncomfortable.

What about social media? What is our role in the age of the Image? How do you project our post-pandemic society?

As for social networks and the online world, the pandemic and what we are doing now is an example: there are very powerful tools and we are using them. They have their pros and cons. You have to know them being aware that we are playing at someone else’s house. But they are spaces for projecting many things and making a lot of diffusion. My bet on a personal level is a well-developed presence at the web level, at the social media level. I don’t want to get addicted or dump uninteresting stuff. A pertinent question is also how to capitalize on all that work. In the end, we put a lot of effort into disseminating quality content on the internet and it is completely free.

You like teaching.

If I didn’t like it, I wouldn’t do it. That is one of my maxims. I understand teaching as an extension of my photographic work. I work to raise awareness through the image. I achieve this by carrying out my own projects and accompanying my students in the development of theirs. In the end they are two sides of the same coin.

“But in the end, both when developing projects and teaching, as I said, I feel the need to raise awareness through images.”

What do you appeal to when you work? What is the driving force behind each project?

It is the million dollar question. And the answer is not worth a euro. I have come to the conclusion that I do what I want but I don’t know why do I want it. The engine of work is the need to do it. When it comes to generating projects there is a drive, there is something that compels me. I don’t sleep if I don’t do my job or if I don’t have things in place or if I don’t take photos. But in the end, both when developing projects and teaching, as I said, I feel the need to raise awareness through images.

I know it may sound naïve but I still believe that showing the work, making it circulate, see and share it can serve to raise awareness. One thing is to share a photo on Instagram, another is to get soundboards and that the people who see your work ask themselves questions. That is success for me.

Did you grow up in Mallorca?

I am from Mallorca and I live near the sea and my family. I feel very privileged for it. Although when I was 18 years old, when I went to study Biology in Barcelona, I was not aware of that privilege. I have developed my career in Barcelona. At that time, 20 years ago, there was a lot of difference between being in a big city or in a place like Mallorca. Today everything has changed, luckily. I have been back for two years and I am also aware that there is a lot of work to be done in Mallorca.

In 2014 you published PAIN with a huge impact. How was this particular book received in the photography world?

It was a hit. As I said, I do things because they excite me, because I like to collaborate with people from any field who does interesting things, I understand that this always multiplies the results. Regarding the book, I was not aware of what I had in my hands. When I thought about it, I said: “I want it to exist, it seems like a wonderful idea. Let’s do everything to make it happen.” This is how we published PAIN. I sold 500 books in three months through my website.

If you’ve read anything about the dopamine discharges that social media brings to our brain: everything is designed for you to be addicted, those three months were a very crazy dopamine rush. It had a mobile ringtone and vibration determined when someone bought. Imagine the scene: I was walking down the street and I was getting money and a dopamine shooting in my brain. Over time I discovered that this was not normal. At the moment you are not aware but when I made the second book (DEVOTOS) the soufflé was lowered and I returned to touch with my feet on the ground and to rent a storage room to store the surplus production.

The book was very well received by the public. And by the critics. Through a very good media plan, I know the enemy from within, it had a lot of repercussions in the media. The final icing on the cake was receiving the Photoespaña award for the best self-published book of the year.

I remember that I was doing an order in Rome and they called me from Madrid. I thought they called me from some insurance company or phone to sell me something and I would hang up on them. When I arrived at the apartment at night and connected to the Wi-Fi, I saw the email in which they told me that I had won the prize. They asked me if I could be in Madrid the next day to collect the prize. I was fascinated by the planning of an organization like PhotoEspaña and that at no time was there a budget for travel or accommodation. Of course, the award did not have an economic endowment.

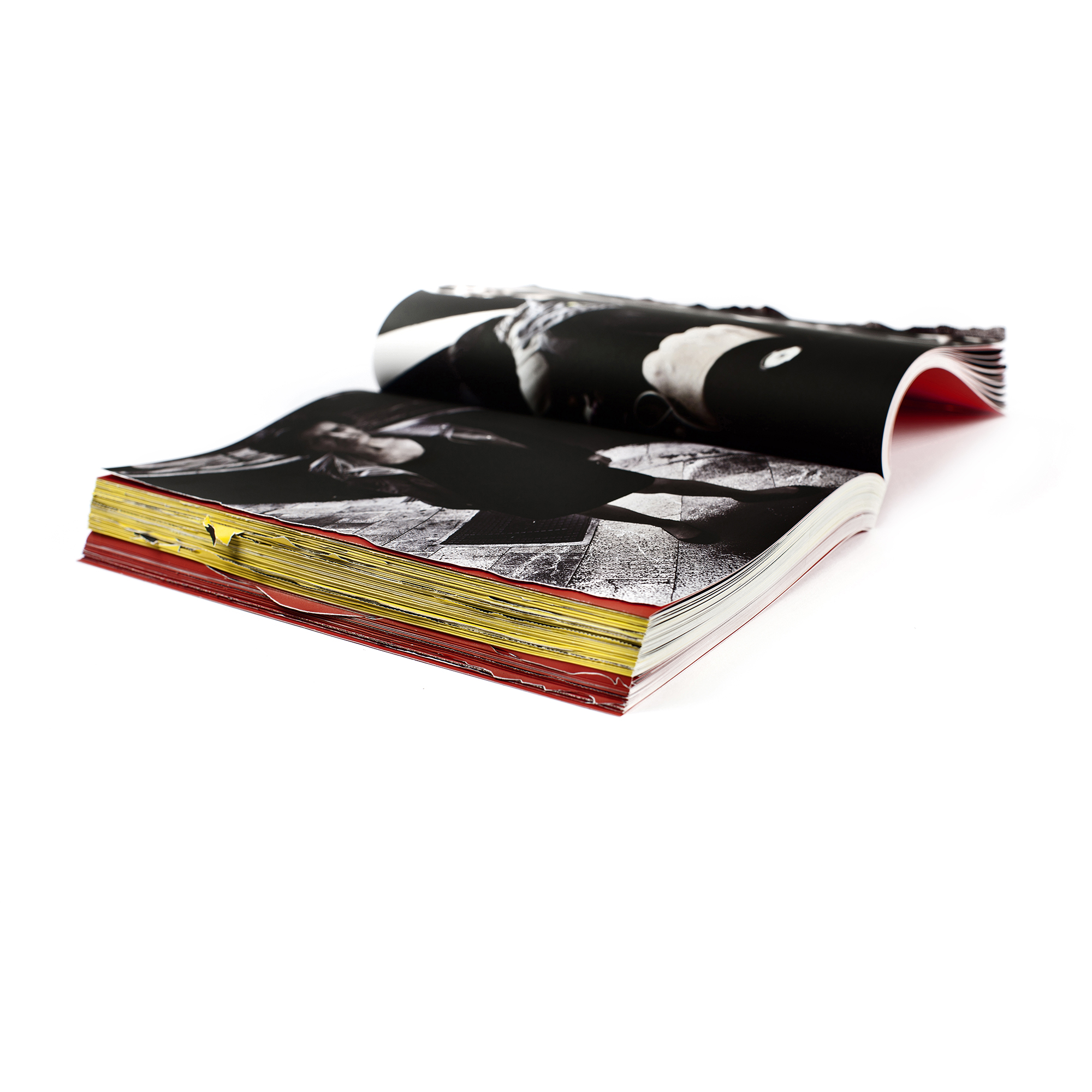

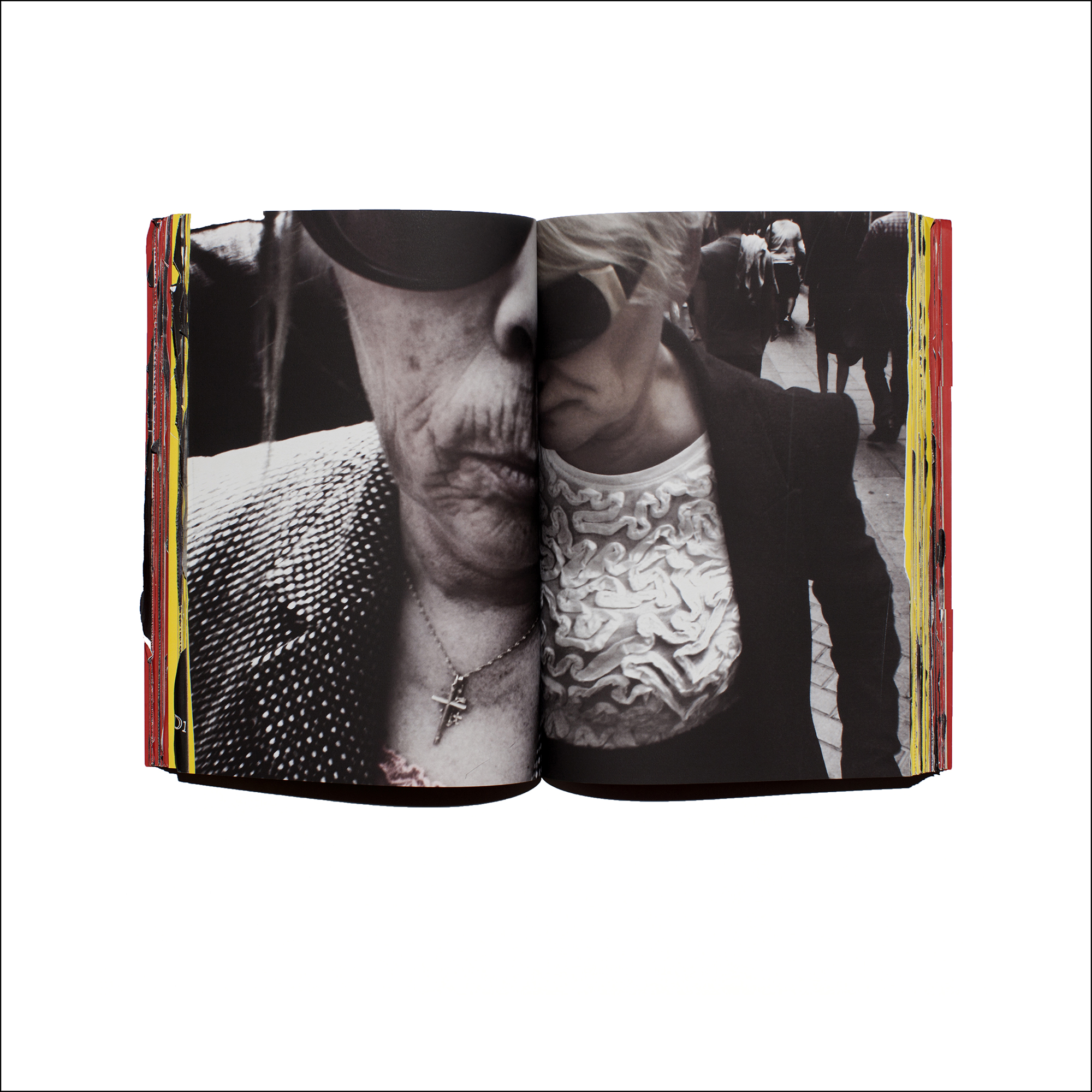

But going back to the book, PAIN managed to get people to talk about it because it was a contradiction in itself: a photography book that apparently has no photographs and you have to tear it up to be able to see them.

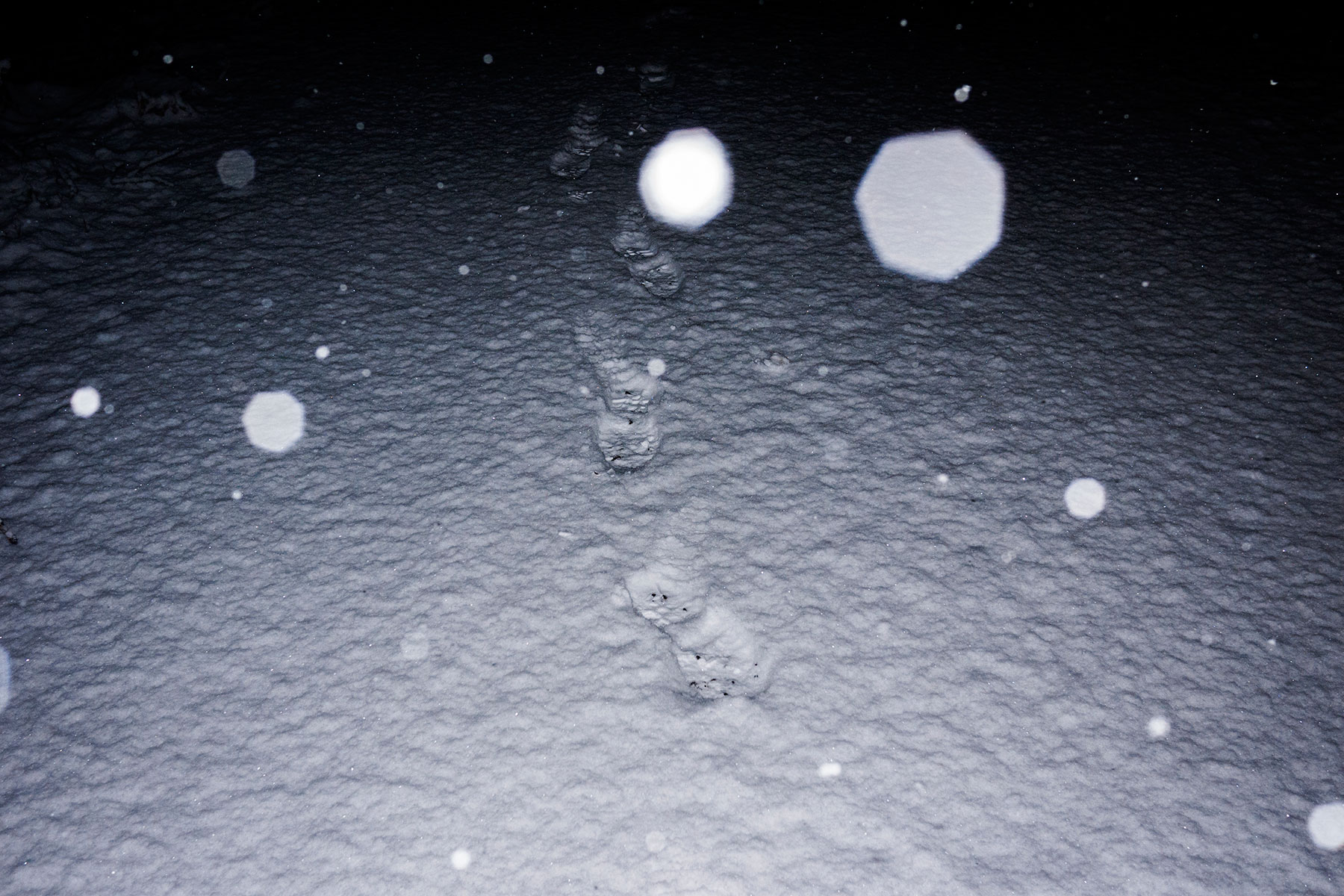

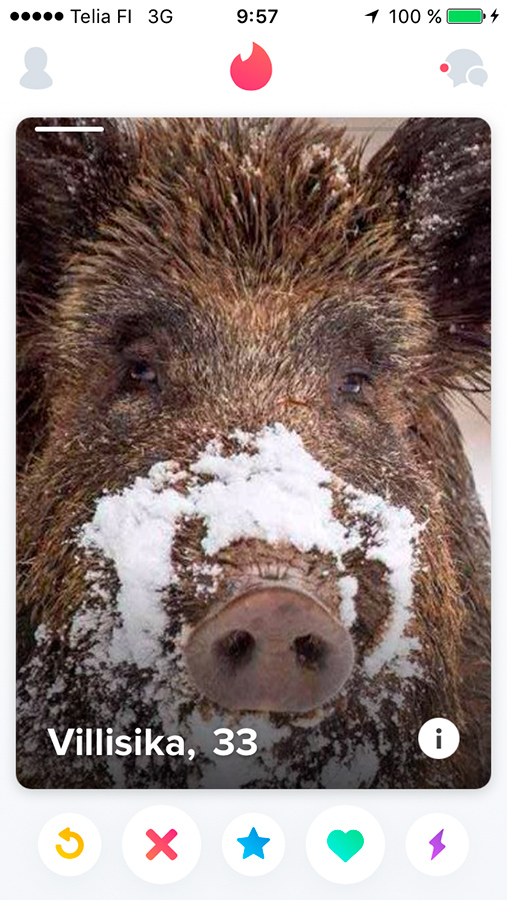

Your project Finland, Tinder and the Dark is disturbing. How was it created?

More than disturbing, I find it moving. The original idea was to explore how a platform like Tinder has revolutionized our ways of relating to each other. I decided to go to Finland for an artistic residency because I needed to change my enviroment. I had been in Barcelona for too long. Finland is a country that I know well, I worked as a biologist there while I was studying, and since then I have been back quite a few times. I thought that the project fitted in quite well with the difficulty or the Finnish idiosyncrasy: there it is very difficult to access the private sphere, the country and its people are cold. The strategy of using Tinder allowed me to access the intimacies of the Finns.

At that time I was giving many photography classes to students between 20 and 25 years old. Among them, the Tinder theme always came out naturally because for new generations it is something common, one more way of relating. I insisted that they do a project on Tinder. But they were not interested. I suppose it would be as if they had told me when I was a student: “Make me a project about the La Boquería Market in Barcelona”.

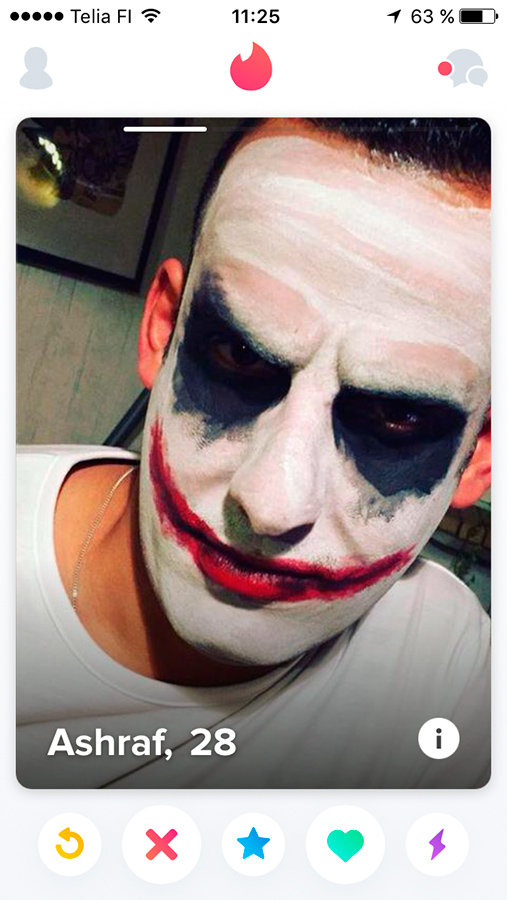

From my vision, Tinder is pure contemporaneity. On the one hand you approach a new form of relationship through apps and on the other hand it contains a very interesting phenomenon which is having a whole archive of users who self-represent themselves through photographs.

Yes, but photos with a deer or a wild boar just hunted, in the snow, bleeding…!

That is precisely what is interesting, how each one represents himself or herself. There was a photo editing job but always trying to preserve the people’s originality and creativity. I wanted to show that there are many people doing wonderful things without being aware of it, without artistic pretensions. To somehow demonstrate that in photography there really is no line between high and low creation. It is only a matter of perception, and that photography is today the most democratic means of expression.

Your work is linked to a certain ironic look, a dense climate and the rescue of kitsch. They have, perhaps, an air of Martin Parr.

Yes, he is one of my references. Another of my references is José Manuel Navia. I heard him in a workshop the phrase: “There is a market for the disgrace of the suburbs and there is a market for the palace chronicle. But there is no market for the disgrace of the palace.” That made me think that it is not necessary to go to the suburbs to look for the misfortune of others because we have it here, in ourselves.

And that made me realize that the social constructions that constitute us on a personal level prevent us from being free. Those are our misery. I find it interesting to put that idea on the table in my work. My way of becoming aware and dismantling it is to show it. I am glad that you find them dense, it is curious because for me they are not. For me they are simply real. But that you feel them dense leads me to think that you are projecting your own social constructions through my work, and that is what is intended.

Does that density finish deepening in Flowers for Franco?

One is always looking for more depth. Perhaps in Flowers For Franco I have reached the greatest depth than I am capable of at the moment, but I aspire to continue descending.

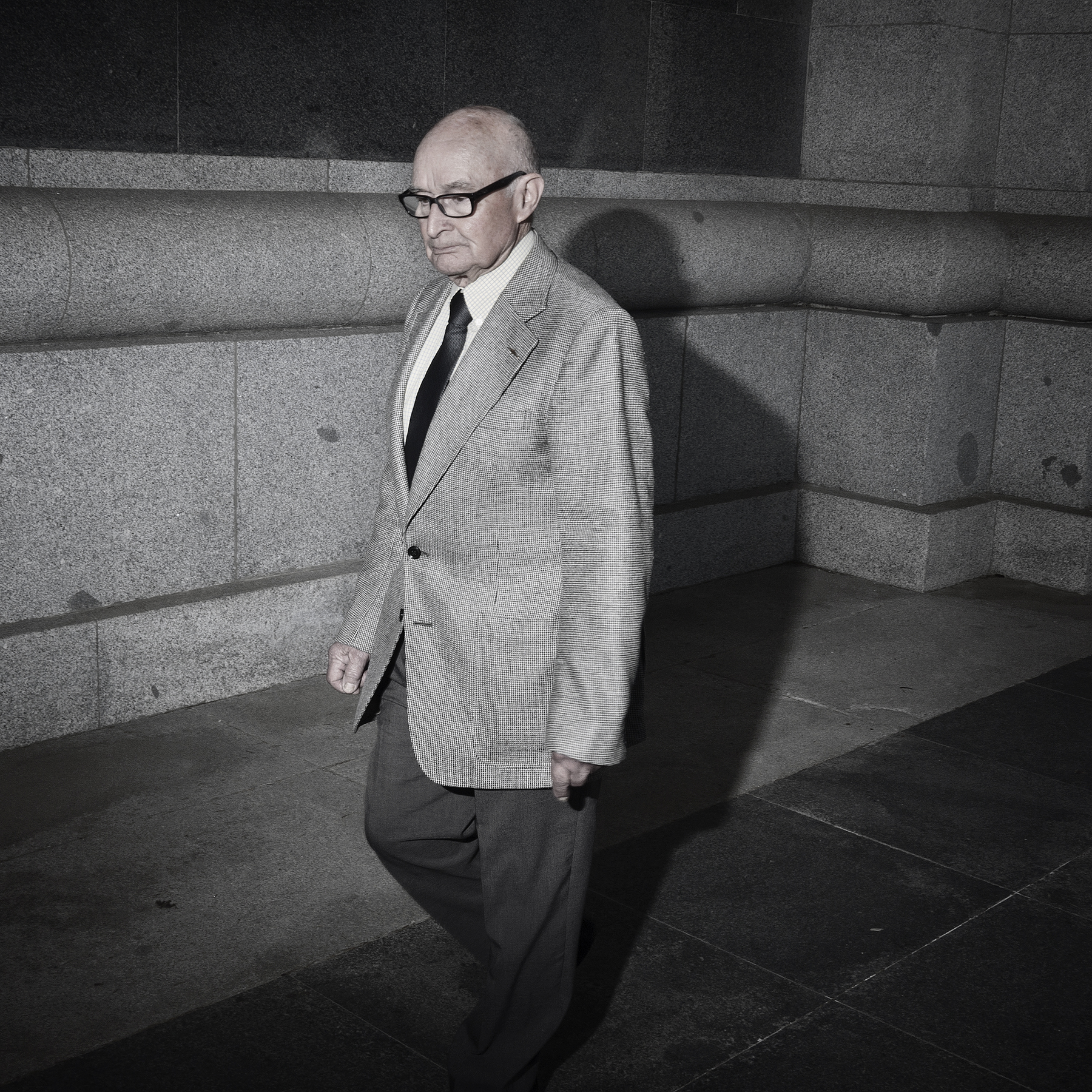

This project also arose by intuition. In Spain there is a place called the Valley of the Fallen; there is the highest cross in the world (120m) and more than 33 thousand victims of the two sides that participated in the Civil War (1936 – 1939) are buried. I was in that place as a child with my parents on a trip we made to Madrid. Many years later I remembered that place when I saw it in the film Balada Triste de Trompeta by Álex de la Iglesia. So I took the backpack, the camera and the flash and went there.

Today Facebook reminded me that this happened 8 years ago. Once there, the visual display of the place makes you aware of the layers of history and suffering that that place entails. And those same layers of history and suffering also make up you as a person. The artist Francesc Torres said: “The most decisive event in my life happened before I was born, it is called the Spanish Civil War.” I was born in the ’80s, there wasn’t even Francoism anymore but that movie continues.

Do your essays represent the need for a reckoning? Does a certain social rebellion move you?

If you look at each other superficially, they may seem like adolescent reckoning, but the will underneath all that is self-knowledge. There is a very strong will to try to understand (me), know (me) and free (me) from what does not belong to me.

Your work transcends politics but it cannot be understood without the Spanish political contradiction that was previously reflected in the Franco regime and today it is due to the confrontation led by Catalonia, the Balearic Islands and to a lesser extent Valencia.

Polarization is key. I recognize that the Balearic Islands have a particular context. We are an island, we are like the Switzerland of Spain. I make my forays into the mainland, I take my photos and then I return to my island, the geographical and the mental one. I do not feel Spanish, if you can feel something like the homeland or the nation, there is a point of distance that allows me to work that way.

An example of that polarity on a personal level is reflected behind the Valley of the Fallen. On a family level my father comes from a humble family. He was able to study thanks to scholarships from the state (Franco). Due to his humble origins, he has always had a very militant and left-wing mentality. My mother, on the other hand, is from the village and she had a different training, and political orientations in her right wing house.

When my maternal grandmother spoke of the war, she was clear that the Republican side were a gang of murderers. If they kill your brother it is logical that you think that.

When it was my father who sometimes told stories of his years at the university, he would tell how the Francoist police tortured, made disappear and killed his companions. It was a fratricidal war, and as such it was a bloodbath between equals. There were winners and losers, but those who lost the most were those whose loved ones were killed.

When I explain this, many people tell me: “The same thing happens in my family.” These issues are not discussed at home because they end badly, everyone has their point of view.

There is a very good vignette from El Roto, I use it when I present my work: it is a little black and white cartoon of a child, with blood on his nose, which says: “Today in class we have given history of Spain.” I think it’s brilliant because if we talk about the history of Spain, we always end up fighting.

What project are you thinking about now?

I have been working on landscaping in Mallorca for a couple of years and on tourism. It came out intuitively, I want to take photos in Mallorca. First I thought locally, then I discovered that the tourist development of the Balearic Islands is closely connected with the Franco regime.

I was awarded with the scholarship of the Spanish Academy in Rome, so I will soon go to do a stay there. I presented a project on the relationship that exists on a visual level between tourism and the iconography of the heritage of Rome. In some way this is linked to the Finnish project, as I will investigate how people present themselves on a photographic level.

In the case of Rome, it would be how people generate images of other images that already exist in the city of Rome, how they relate to them, to heritage, and how tourism has generated a type of relationship that, from my point of view , it is quite hollow. The tourist class mostly visit Rome to see the great monuments that they already know from photos to be photographed in them, but they do not know the history and what happened there.

It is the spectacularization of history. That, in turn, is linked to my work in the Valley of the Fallen, a place that many of the people who visit it are unaware of and do not even question where they are. Added to that is how COVID has affected the tourism phenomenon.

I find it very enriching to be able to get to know a country through its cultural and photographic creation.

What do you know about the photography that takes place in Latin America?

Through Vist I am seeing things that are being explored in Latin America. Argentina is the country with which I have the most relationship, I was lucky enough to do an exchange a few years ago with artists from there. I was in the province of Córdoba and it was interesting.

I feel like there is a very experimental stage. At the creative level, quite cutting-edge things are done, outside of the canons. There is a lot of creative movement. And this idea of creating bridges seems fundamental to me.

We all speak Spanish, but it is also necessary to generate more interaction, more exchange to see what happens in other places, what others are doing. I find it very enriching to be able to get to know a country through cultural and photographic creation.