An image that is read, a poem that is seen

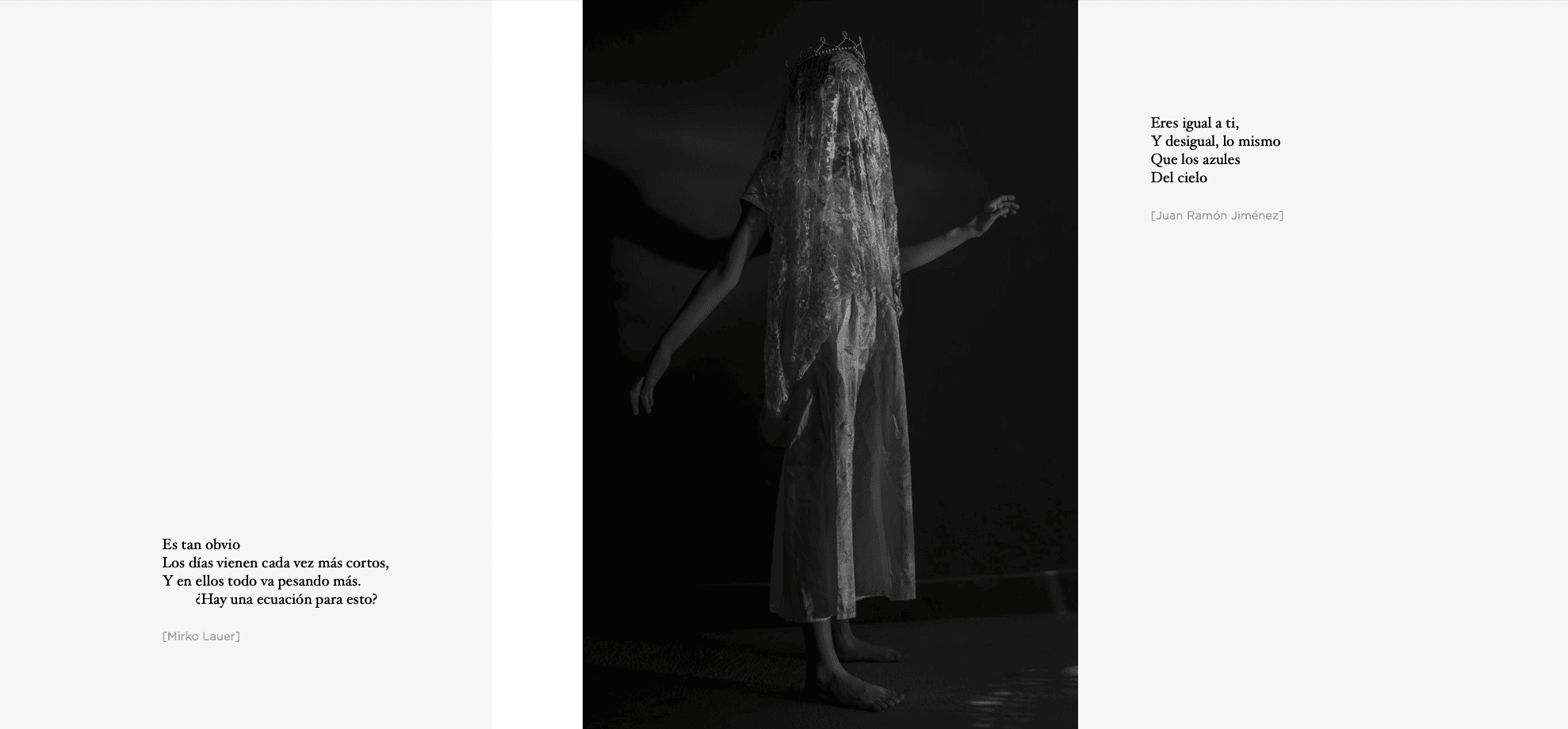

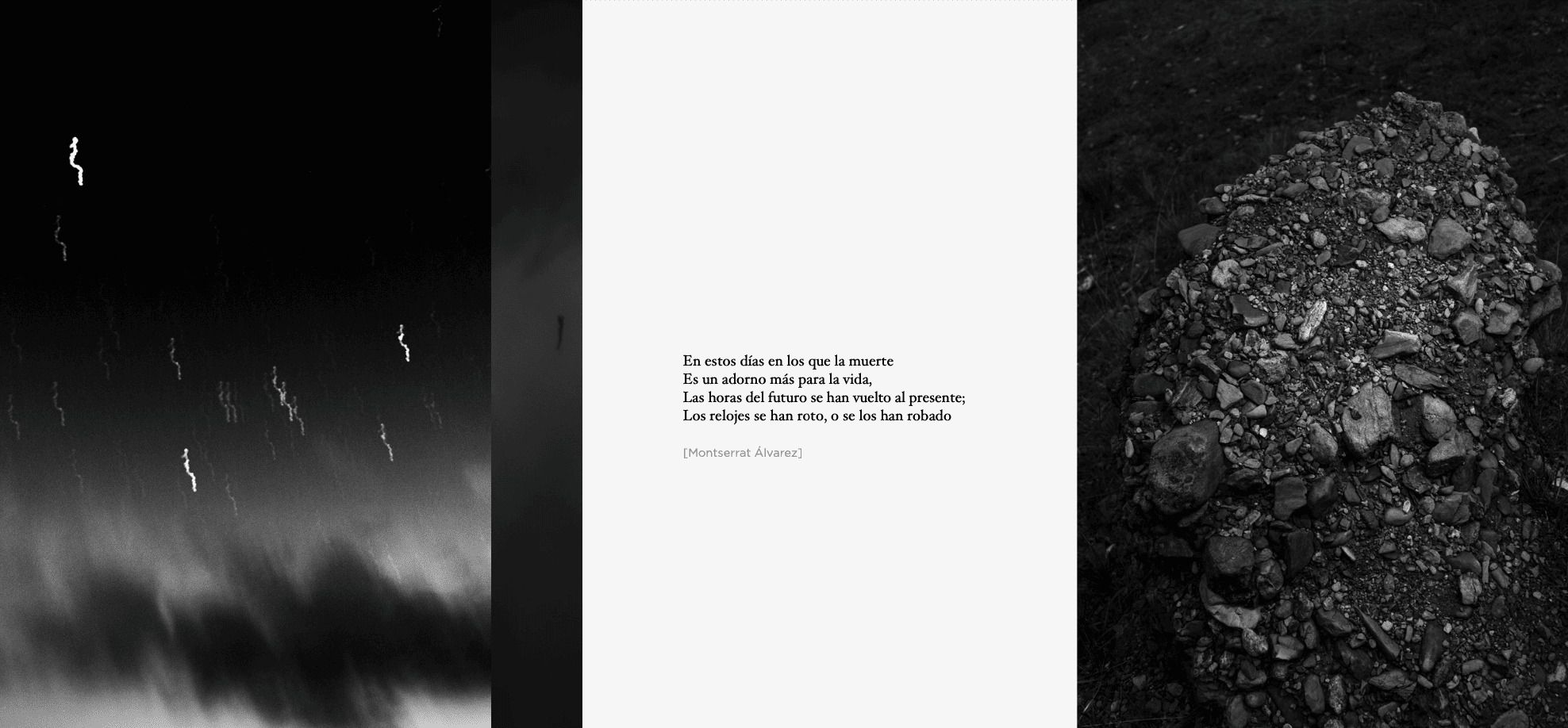

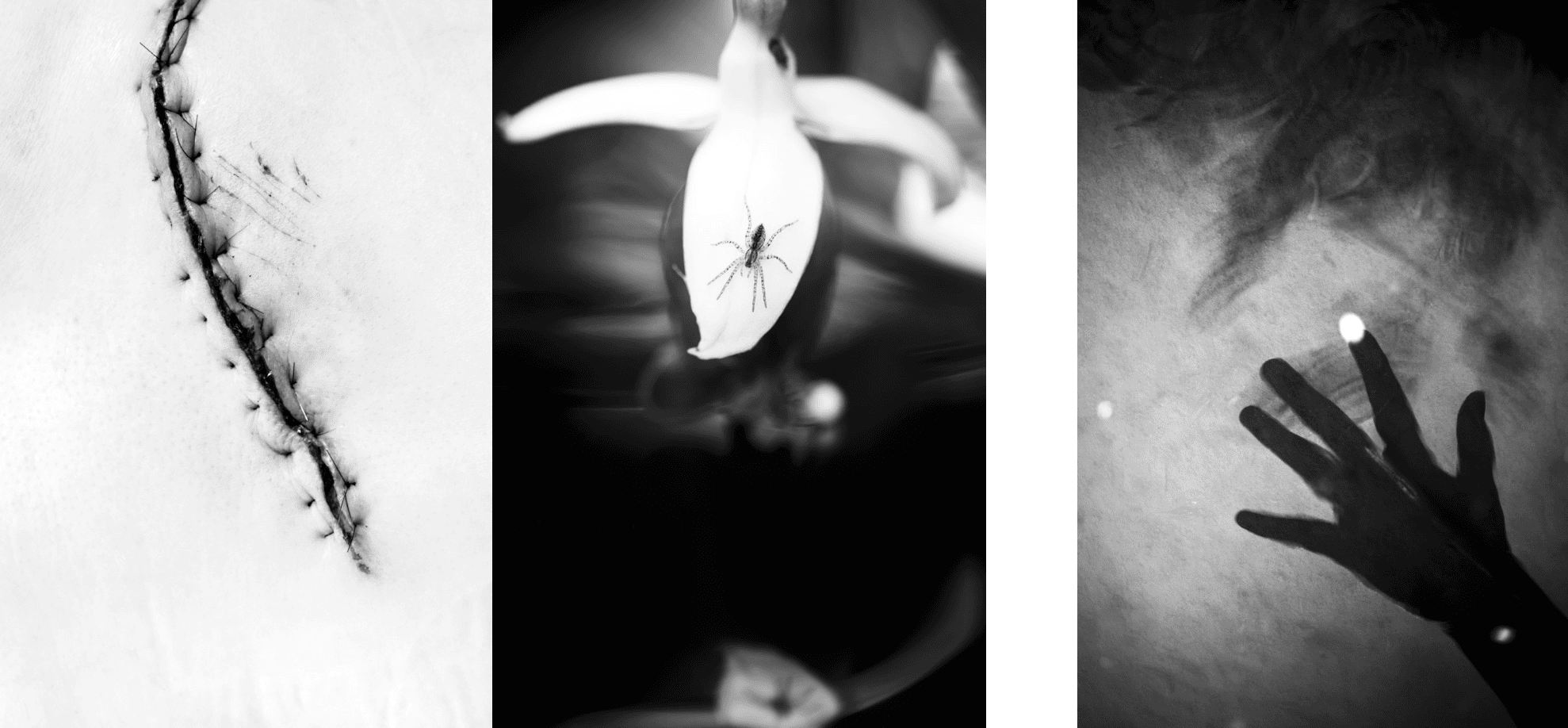

“Contrapunto” is a photobook reproducing the virtual correspondence between the photographer Lucero del Castillo and the cultural critic Víctor Vich. An intellectual game unfolds within its pages, which is also a mystery for the senses. It lies in the elusive way del Castillo’s personal archive images respond to or collide with the poems selected by Vich and vice versa.

Por Alonso Almenara

Contrapunto is one of the most common techniques in musical composition, but it is also one of the nightmares of conservatory students. The difficulty lies in combining two or more melodies without one being a mere accompaniment to the other while maintaining the independence of each. And this is without losing harmonic coherence. Such situations are unusual in real life. Rock bands and couples break up for that reason: because contrapunto is difficult. Because the voices are not equally autonomous or maintaining unity requires discipline, which always clashes with freedom. It happens in activism. It happens in the challenge of combining the personal and the political.

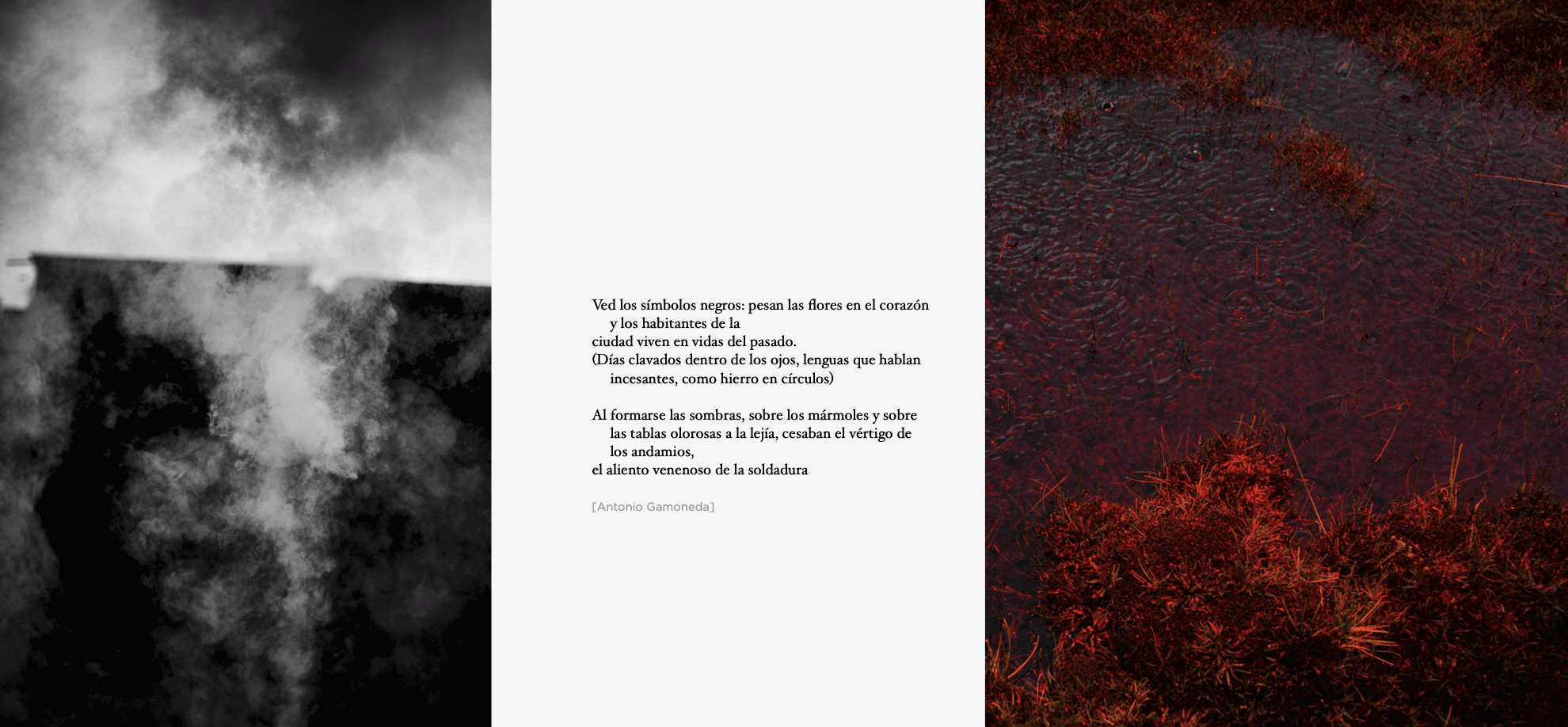

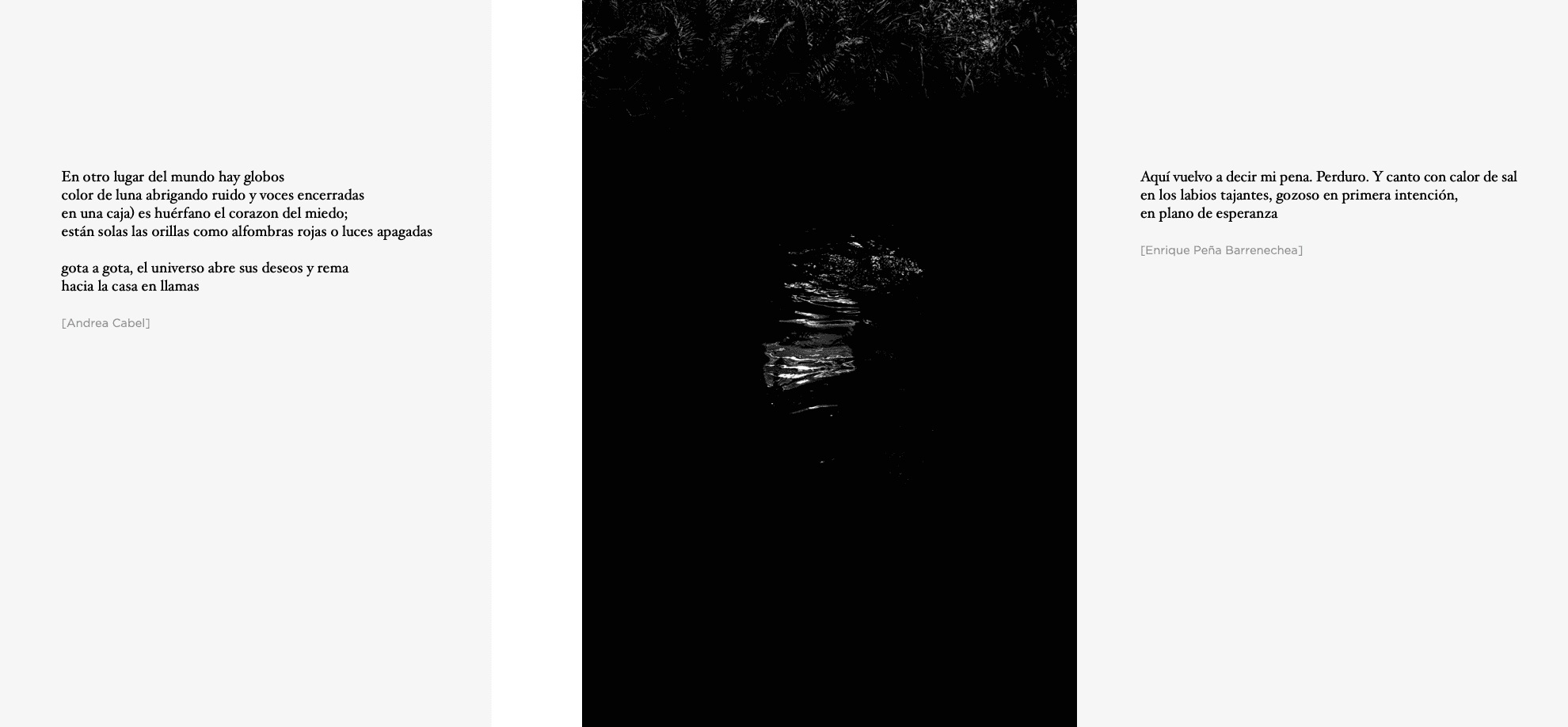

In the photobook “Contrapunto” (Meier Ramírez, 2022), the photographer Lucero del Castillo and the cultural critic Víctor Vich, both Peruvians, exercise this complicated art, putting their voices into dialogue and two different types of artistic creation: poems and photographs. Their intention, they write, is to “show the contact” between both disciplines, “but also the separation; the bridge, but also the void.”

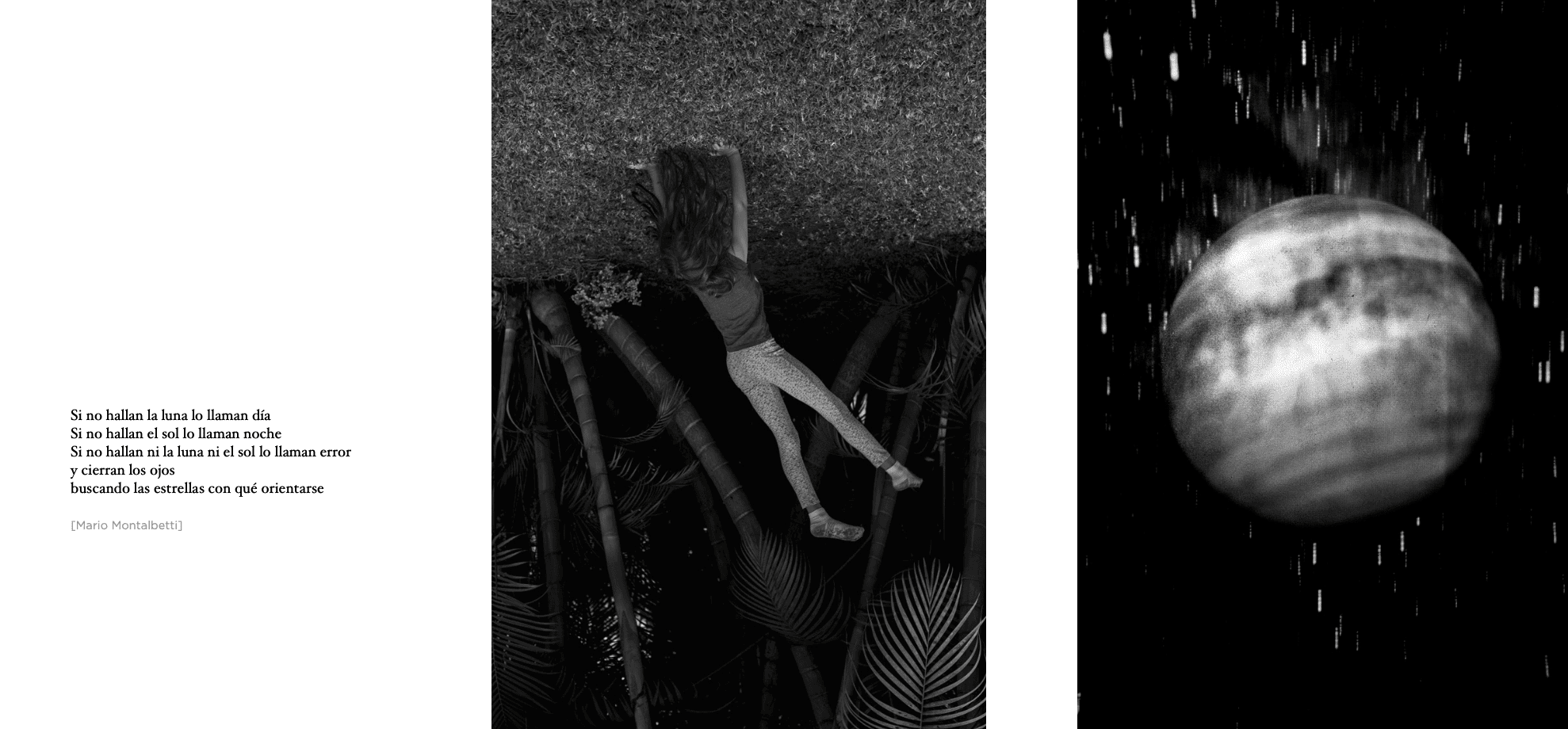

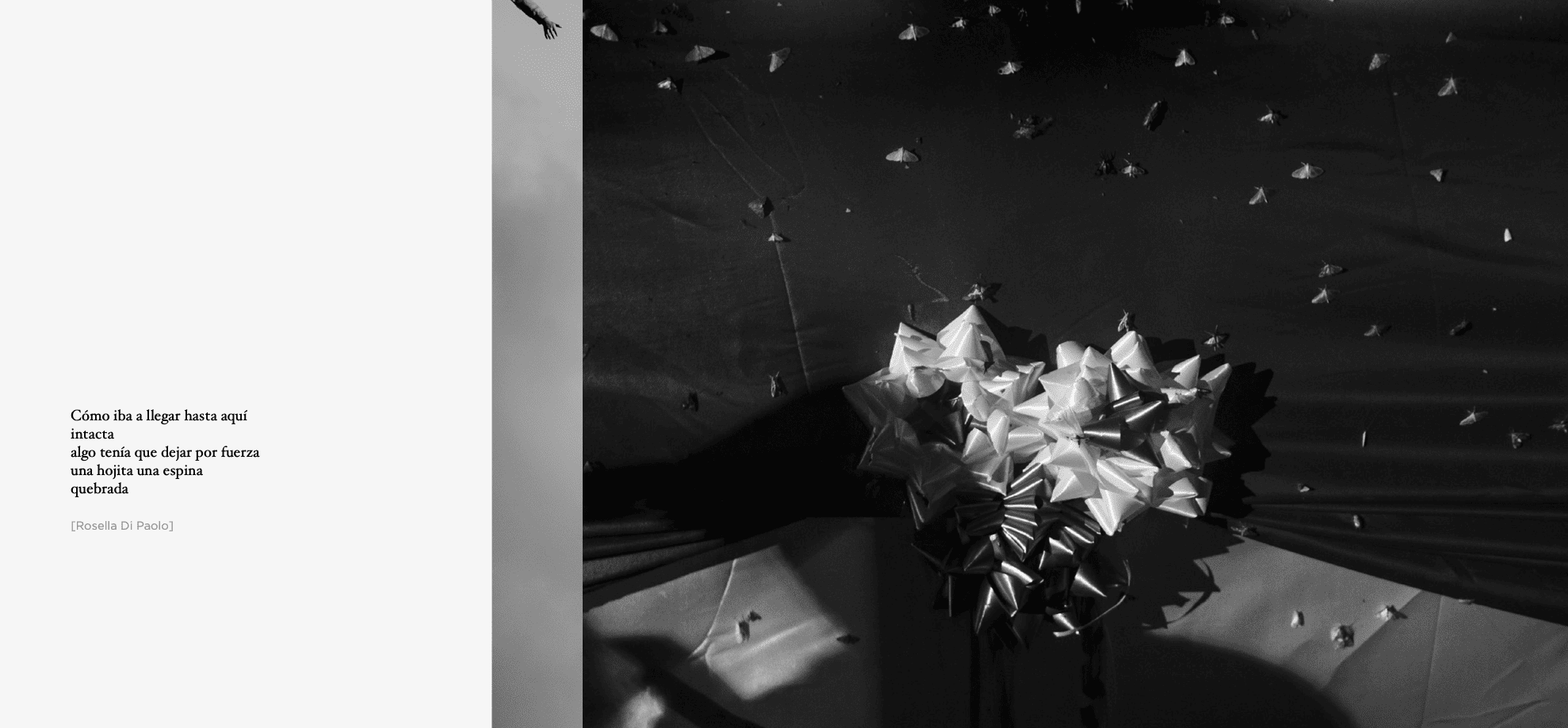

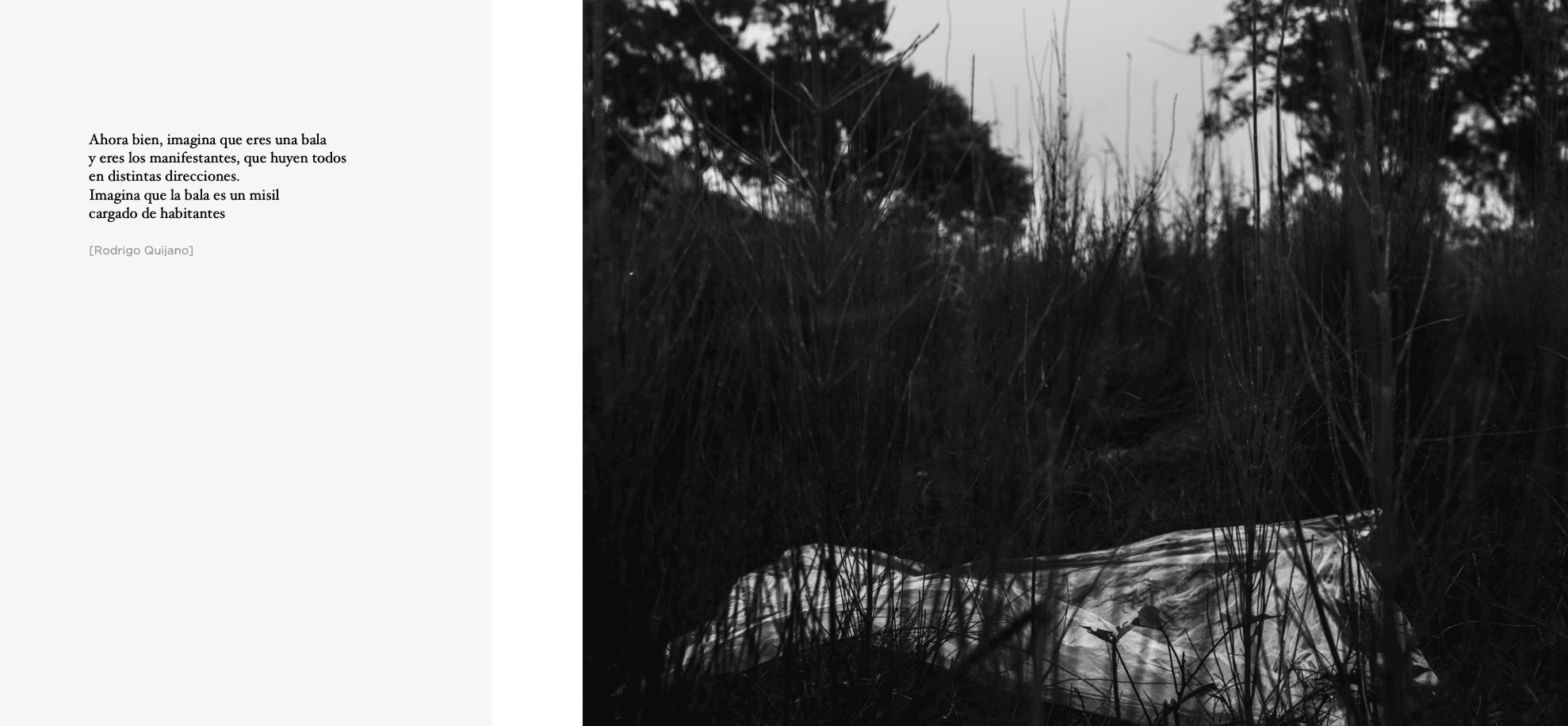

Del Castillo is responsible for the images. She has been a photojournalist for the newspaper El Comercio for years. Here, she shows a different facet: her work is not realistic but allegorical, linked to the observation of nature and childhood memories. On the other hand, Vich selected excerpts from poems: there are verses by Louis Aragon, Rodrigo Quijano, and Mirko Lauer, among others. He is the author of books like “Contra el sueño de los justos: la literatura peruana ante la violencia política” (2009) and “Poéticas del duelo: ensayos sobre arte, memoria y violencia política” (2015), in which he examines responses to the period of internal armed conflict (1980-2000) in which Sendero Luminoso confronted the Peruvian state from the field of cultural production. He has also written about poetry, as in the recent book “César Vallejo: un poeta del acontecimiento” (2020), a Badiouian reading of the work of the Peruvian writer.

“Contrapunto” is a small book of 60 pages, comprised of 42 photos and 24 poems, printed thanks to the funding received by winning the 2022 CAP Creation Award from the Pontifical Catholic University of Peru. The authors mention that it originated from an email correspondence, and the page layout follows more or less the sequence of that original exchange, in which they dialogued with photos and poems—and said nothing more. But the book is also an open work that allows the reader to choose their reading order and establish new relationships between the material. “We were interested in deconstructing the opposition between looking and reading, between photography and poetry,” says Vich. Photography becomes a text; poetry becomes an image; the image is read, and the poem is seen.

The project includes an exhibition that opened on August 10th at the Alianza Francesa de Miraflores in Lima and will run until September 16th.

How did you turn an email exchange into a photobook?

Lucero: The project was somewhat my initiative. Víctor has been my teacher in two master’s programs. He taught literature and started sharing poems with me. I wasn’t much of a reader before, but I eagerly read what he sent me. And so, as I read, I thought of responding with a photo every time he sent me some verses. A picture of mine that would dialogue with the poem. He would respond with another poem, I would send another photo, and so on. That virtual correspondence lasted about a year. It was like a game.

Interestingly, we didn’t say anything else: we didn’t comment on the photo or the poems. But, we realized that the conversation was still developing and self-sufficient. At this point, Víctor suggested that what was initially just correspondence with no pretensions could become an exhibition. At first, I wasn’t very convinced because I didn’t know what we were doing. It simply provoked me to do it. Now that I look back, I realize that unconsciously, it was a search, a desire to return to photography. I had stopped taking photos for two years, and this appeared as a pretext to return.

Víctor: I want to emphasize that Lucero said that the correspondence became autonomous and self-sufficient. Or rather, it became a different type of conversation. It was about finding a language different from the usual. And through that conversation, we were exchanging stories, ideas about life, testimonies, things that had happened to us, things we thought and felt at that moment, expressed in a different way: neither in oral language nor in visual language, but in the counterpoint of images and poems. The discovery of that autonomy and other conversation registers seemed aesthetically powerful and exciting.

How are a poem and a photograph alike? How do they differ?

Víctor: In principle, they are two completely different registers. We didn’t want to turn the poems into illustrations of the photographs or vice versa. In the relationship we propose, each record maintains its autonomy, but at the same time, both registers point towards something that can be a shared meaning or, rather, a collision. The relationship between the poem and the image is dynamic. Sometimes it’s a dialogue, sometimes a clash, sometimes an escape. Sometimes, the verse only dialogues with a small part of the image; sometimes, the idea contradicts the poem. We’ve been interested in presenting a dynamic relationship between two different registers, not a relationship of subordination of one to the other. Not a relationship of mutual understanding and harmony but a relationship of friction and ongoing play.

Lucero: Both registers have that freedom of interpretation, and we’ve wanted to emphasize it in the book by opting for an open structure where poems and photos can be combined in many ways. We don’t want to anchor what is naturally free.

How does this project relate to each of your personal journeys?

Lucero: I stopped doing photography projects for two years because I decided to pursue a master’s in anthropology. And that decision had to do with me starting to question how I was creating, how I was researching, how I understood reality, and I realized I needed other things. When I started the master’s, I was very clear about what my thesis would be about masculinities and violence. I wanted the thesis to be input for creating something visual afterward. So, I dedicated two years to searching for theoretical tools and other research methodologies without completely abandoning the need for visual creation. And I think now I’m becoming aware of what this correspondence with Víctor meant. I wanted to find myself. I did not start a new project, but look back because the photos are from my archive. I’ve only taken two new photos for this project. It was an opportunity to reconnect with my photographs, with the things that concerned me. Every time I received a poem, I immersed myself in my archive, remembering the context in which I took each photo and easily decontextualizing the images and thinking about them differently.

Víctor Vich: For me, it has been an unprecedented experience. It’s the only time I’ve felt somewhat close to artistic creation. Although I’m not the author of the poems, and my work consisted only of looking at the photographs and relating them to some verses I remembered, I felt that this work was creative. I am a teacher who has written a lot, and I have always felt that my writing is fundamentally conceptual and political. It has a creative dimension but within the framework of a rational academic argument. Not here. Here, a new artistic dimension emerged in me. It was like confronting a new identity.

The book is quite personal and reflective, which surprises me a bit considering Victor’s political texts or Lucero’s photojournalistic work. The question is whether this turn inward relates to the political situation in Peru, which is very deteriorated.

Victor: The correspondence took shape not only through the images and poems we sent each other but also based on the problems brought by the pandemic or the political situation. And although the latter is not the most crucial aspect of the book, it is present. It is even present in the structure itself: almost in the center is a poem by Rodrigo Quijano that mentions the deaths in protests and a photo by Lucero that could be read almost as a common grave. Then, there is a poem by Montserrat Álvarez about the deterioration of institutions, a collective life in the country, and so on. The political reflection is present as a context that runs parallel to the private questions. In that sense, the book also establishes a counterpoint between the question of subjectivity and social life.

Lucero: It should be taken into account, in any case, that the book is related to a more figurative register, not documentary photography. That’s the way I’ve been photographing. But the political aspect also has a place there. The themes that interest me the most, such as gender identity, are present in the photos of girls we have included.

Victor: As you mentioned, Lucero has been a photojournalist for the newspaper El Comercio for many years, and her photos were realistic. They were images of politicians, events, and accidents. And in my academic work, I have also been discussing the current situation. This book was like an experiment; it talked about the same things but in a less realistic language.

It is essential to mention that Lucero has developed these images parallel to her work as a photojournalist and has almost never shown them. In my case, something similar happened: I am a poetry reader, and that was something I wanted to showcase. To reveal that less realistic side, more committed to open symbolism, to the power of aesthetics.