A performance, a knife, and a chroma in the face of media opportunism | Fresco EP#4

In 2018, the far-right Jair Bolsonaro was stabbed during an electoral event before winning the elections. The attack improved his public perception and facilitated his path to power. In response, Brazilian photographer Rafael Roncato suspected the situation was strange and decided to take action: from the other side of the world, he portrayed how that attack had occurred, using green screens, big headlines, and fake blood.

By Luciana Demichelis

The right wing is advancing worldwide. Extreme right-wing parties, once on the fringes of the political spectrum, are now gaining positions of power within major right-wing parties in Europe and Latin America. In Argentina, the liberal party La Libertad Avanza won the pre-elections with over 30% of the votes, while in Italy, Sweden, and now Finland, among others, openly conservative parties are already in power.

In response, Brazilian photographer Rafael Roncato suspected the situation was strange and decided to take action: from the other side of the world, he portrayed how that attack had occurred, using green screens, big headlines, and fake blood. The project invites us to reflect on how representation and staging can help us rethink how the world uses photography. In episode #3 of Fresco, we talked to him before his trip to Amsterdam and after winning first place with the ‘Tropical Trauma Misery Tour’ in the Lovely Prize from Lovely House Publishing at the Imaginária Festival in Brazil.

How did you personally experience Bolsonaro’s victory in Brazil?

Even though Bolsonaro’s government was in power between 2019 and 2022, I have a vivid memory of a moment that I believe was crucial for his victory as the 38th president of Brazil: the knife attack in 2018 during his campaign rally in Juiz de Fora, Minas Gerais.

At that time, I was outside Brazil participating in the Verzasca Foto Festival in Switzerland when I received a video via WhatsApp of the moment he was stabbed in the midst of the crowd. The video was shaky, low-quality, filmed directly in the middle of the audience, and showed little more than movement and Bolsonaro being carried amid the confusion. I remember the first message I sent to the person who shared the video with me was, “he’s going to use this attack to his advantage,” I immediately added, “he’s going to become president.”

Regardless of the versions regarding the integrity of the attack, that moment would be used in his narrative of triumph through dramatization. His media presence seized on the attack in every aspect, capitalizing on the curiosity and exploration of the media to amplify his image and, consequently, his ideas. Now, he had narrative control and the attention of everyone, both supporters and opponents. It’s a strategy of the far-right and fascism that we see repeated over time and in different countries, adapting to each reality and culture. This way, Bolsonaro can control how and when his image is used, exponentially leveraging his ideology, polarization, and violence and avoiding important debates that would jeopardize his candidacy and proposals. A few months later, unfortunately, he became president.

In 2019, with him in power, we witnessed a rapid decline in many rights, and his ideology spread to every corner, cell phone, and mind of the Brazilian people. At that time, while still working for major Brazilian media, I was invited to photograph the departure of Cuban doctors from the government program “Mais Médicos.”

In partnership with Cuba, this program brought doctors to disadvantaged regions of the country to improve healthcare access and quality for the population. I remember talking to a woman waiting at a health center: she, desolate, was trying to find a way to treat her husband diagnosed with terminal brain cancer. His examination and surgery were rescheduled and postponed until after the likely date of her husband’s death. Seeing these people without access to healthcare, missing their scheduled appointments, with local doctors overwhelmed by the departure of Cuban support was heartbreaking. This situation became emblematic of the consequences of Bolsonaro’s government’s victory.

And then came the COVID-19 pandemic, and this death project extended to over half a million Brazilians.

How did you start producing your series “Tropical Trauma”?

In 2020, amidst the pandemic, I pursued a Master’s in Photography and Society at the Royal Academy of Art in the Netherlands. Due to my background as a journalist, having worked in documentary photography, I was interested in the intersection of media, conspiracy theories, and manipulation, heavily influenced by the consequences of post-truth and the use of photography.

While working on a previous series that connected archives and conspiracy theories called “The Wireless Anatomy of Man,” I studied some manipulation techniques and triggers used to spread these theories. Inspiration arose from a series of attacks on 5G technology transmission towers that took place in some Dutch cities and other parts of the world. There was a paradox in this act that made me want to reflect further on the relationship between social media, manipulation, and the irrationality of ecological cameras.

The beginning of the series occurred amidst my frustration at seeing Brazil being assaulted by Bolsonaro’s government propaganda and the absurd events that were growing daily. From afar, I followed the assault on the flag, the colors, the values, and many lives. Initially, in the first year of the master’s program, the idea was embryonic, just a distant intention. Influenced by previous work and the use of fiction/speculation in photography, I remember joking with a friend that I would do a project about the ambiguity of the knife attack that Bolsonaro suffered. At first, it was a joke that began to take shape and made me understand that it didn’t matter whether the attack was planned or real. The damage had already been done, and that act was crucial to his rise to power in the country. Therefore, the project aimed to play with the fine line between documentary photography and fiction.

Due to the pandemic and my inability to return to Brazil, I looked for ways to produce remotely. Using a photography studio was one of the ways to produce in the Netherlands, as well as my photographic archive and collaboration with a Dutch actor who bore some resemblance to Bolsonaro. Since everything was about fake news, performance, and manipulation, I decided to connect all the elements in one place to construct a sort of polyphonic theater of Brazilian political games.

What do you think are the links between photography and performance?

Photography is not innocent. It tells a specific story from a particular angle, with specific intentions. Photography is always a performance, whether of the subject or the person taking the photograph.

That applies to media and journalism, and believing in some supposed impartiality is naive. In this way, it always relates to the propagation of an idea and a point of view. As a journalist, I ask essential questions: what, when, where, how, why, and, above all, for whom?

In the case of politics, photography, and performance go hand in hand. It’s pure propaganda, used to persuade and spread an idea.

Did the project have previous references? What were they?

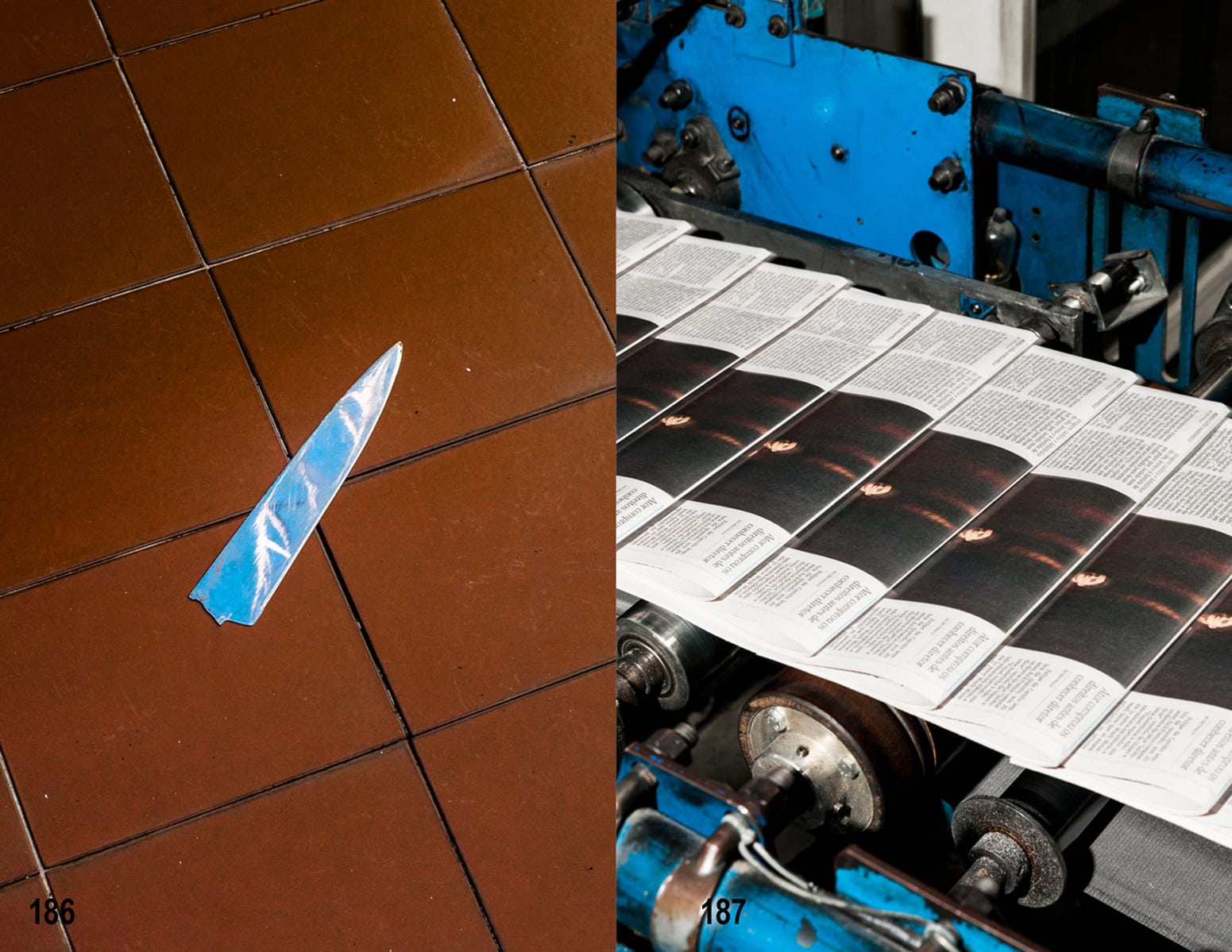

My projects are always a kaleidoscope of references. Some simply make sense to me and become internalized during the production phase. Others have been guiding and helping shape both the theory and the practice. Since the knife is an important motif in the project and the book, the photograph “A Mão e a Faca” (1949) by Portuguese artist Fernando Lemos was a major inspiration. The tension and suspension of the moment captured in that image were essential for the narrative construction of part of the project.

Working at the Museum of Modern Art in São Paulo also helped me bring references from artists who influenced me during my years there. Regina Silveira and her screenprinted series “Trampa para Ejecutivos” (1974) have been imprinted in my mind since then. Contemporary Brazilian artists like Jonathas de Andrade, Barbara Wagner, and Shinji Nagabe were instrumental in shaping my repertoire and expanding my experimentation in photography. Even the most recent book by photographer Jonas Bendiksen, “The Book of Veles” (2021), a documentary work on the production and economy behind fake news.

A more unconventional reference was the newspaper “Morre Bolsonaro,” organized by the writer and friend Ronaldo Bressane, which gathered 28 Brazilian artists, including writers and cartoonists, to write obituaries for his death from various causes. This form of dissemination and use of printed material was important in developing my work, inspired by Marshall McLuhan’s “The Medium is the Massage.” These are just a few examples I can recall from memory now, but there are many more interconnected artists, works, and relationships out there that I am not doing justice to now.

What were your initial reactions when presenting the project during your classes or in open calls?

This work had different perceptions for different audiences. Initially, I presented the work as a culmination of my master’s degree, where a more international audience looked at the subject and evaluated the theory and practice. The work was very well received, and I benefited from the input of many fellow students, friends, and professors. In this construction, my advisors Andrea Stultiens and Donald Weber were fundamental and other artists like Max Pinckers and Adam Broomberg. In these circumstances, Brazilian designer Mateus Acioli was the first person to see the material while we worked together on the photobook production. He liked it and further motivated me to play as I had envisioned.

As much as the story unfolded in Brazil, many themes were recognized and amplified beyond this geographical area. The history of my country serves as an allegory for a universal problem that we face and must be discussed. This universality was seen, for example, in the organization FOTODOK, based in Utrecht, which selected me for their Lighthouse talent program.

Regarding the Brazilian audience, the impact seems to have more strength when addressing our recent and ongoing tragedy directly. Many of the images, symbols, and narratives found in the project are easily recognizable and carry a completely different weight in international perception. There is less explanation of what happened and more attention to the complexities and tactics used by the Brazilian far-right, allowing me to play with the images more freely and, therefore, work with layers of perception and humor (in tragedy).

The photobook has been shortlisted in the most important photobook dummy awards in the world, such as the Fiebre Dummy Awards, Kassel Dummy Awards, Images Vevey Dummy Awards, and received a special mention in the Dummy Awards at the Hong Kong Photobook Festival. It recently won first place in the Lovely Prize from Lovely House Publishing and at the Imaginária Festival in Brazil. I am very pleased with the reach and attention the work has received, allowing for discussing the topic.

What are you currently working on?

Over the past year, I’ve been promoting the work, submitting the photobook to various awards, and presenting it at reviews and to various people. It was a good way to take a break from all the violence the project entails and breathe in search of new developments for Tropical Trauma and other projects.

At the moment, I’m dividing my time between publishing the book, working on another book project that I feel the need to complete (a collaboration with the cartoonist Laerte, whom I photographed ten years ago), and drafting a new project based in the Netherlands, especially in the city of The Hague, where I currently reside. Being in the City of Peace and Justice, the epicenter of Dutch political power, I gradually became interested in investigating the invisible relationships of power and control that go unnoticed in our daily lives.