The Wembler’s, patriarchs of Amazonian cumbia

Peruvian filmmaker Luis Chumbe has premiered his documentary “Amazonian Sound,” in which he examines the musical career of Los Wembler from Iquitos, where he was born. This legendary band, founded in 1968, is partly responsible for initiating the Amazonian cumbia revolution. It remains active half a century later despite the difficulties it has overcome, including the deaths of three of its original five members during the pandemic.

By Alonso Almenara

Luis Chumbe’s new documentary, focused on the legendary band Los Wembler’s from Iquitos, includes sequences in which we see the group performing on barges in front of a crowd distributed in “pequepeques” and other smaller boats in the middle of the Amazon River. The feeling left by this spectacle, conveyed by many scenes in “Amazonian Sound,” is that some things can only happen in Iquitos.

It was there that Amazonian cumbia was born, that hybrid music that emerged when the electric guitar was introduced into tropical music, influenced by English rock. But the city is another unique blend, with its rhythm of moto taxis, rain, and mosquitoes, a constant celebration, “a daily sweat,” as Luis puts it. This peculiar mix of sensations has rarely been captured by Amazonian cinema, but it’s something that this film prides itself on finally portraying.

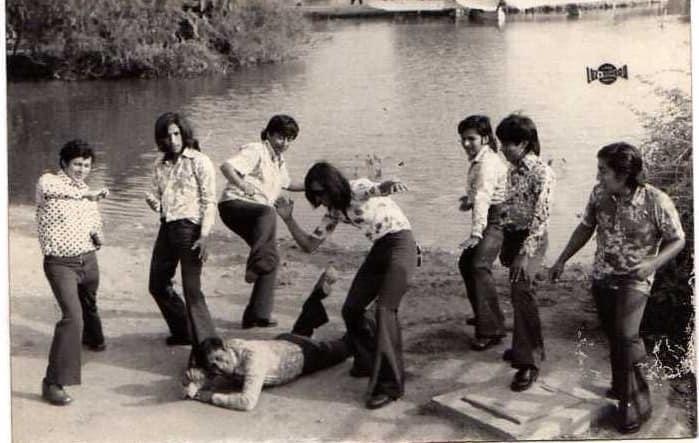

At the heart of the feature film is a portrait of the most important musical family in Iquitos: the Sánchez Casanova family. Five brothers – Isaías, Jair, Alberto, Jairo, and Misael – formed Los Wembler’s in 1968, the same year that Los Destellos and Juaneco y su Combo appeared, and together with these bands, they laid the foundations of Amazonian cumbia. Among their most famous songs are “La Danza del petrolero,” “Un silbido amoroso,” “Sonido amazónico,” and “Amenaza verde.”

“They have always been geniuses to me,” says Luis. “My interest in their music comes from my grandmother, who was a big fan of this group. She has always been inferior but managed to see them. I come from a very festive family, to be honest.” “Amazonian Sound” premiered on August 15th at the Lima Film Festival, following a four-year production period marked by challenges related to the COVID-19 pandemic. The film will be screened in commercial theaters in Iquitos starting on January 5 next year, coinciding with the city’s anniversary date.

How did this project begin?

It happened by coincidence that a friend of mine made a short film that used music from Los Wembler’s in a scene, and since she lives in Spain, she asked me if I could contact them to obtain the music rights. Through some friends, I reached Mr. Jair, the voice of Los Wembler’s, and he kindly agreed to grant us the music rights without charging us.

After that, we started talking. I had already been exposed to their music as they performed at an urban art festival we used to organize with some colleagues in Iquitos. Additionally, I am a documentary filmmaker, so I always watch for compelling stories. I saw something I liked in Jair. I admire his music and his warmth. Conversing with him is very pleasant. He is passionate about what he does about who he is.

One thing that touched me was when he said, “This year marks our 50th anniversary as a group, and no one is going to celebrate it.” They are very proud of what they’ve accomplished, but, indeed, there isn’t much love for them in Iquitos. The gentlemen needed to do something. They had composed twelve new songs, of which they had already recorded several, and they wanted to shoot some music videos to connect with the youth.

They had just returned from a European tour at that time, right?

That’s correct. It all began in 2012 when they went to Italy with Marca Perú. It was a fresh start for them after being dormant for so long. Suddenly, they were experiencing success again and performing to large crowds in Europe. So, it was nice to find them at a time when they felt recognized. Their music is not as widely heard in Peru anymore, but it was very popular in the 70s and 80s. It was neighborhood music: Los Wembler’s came from very humble conditions. It’s a type of music that speaks of that time, of people who moved the masses.

When I met them, they were very happy to have had that experience in Europe, but at the same time, they lamented the lack of recognition in Iquitos. I found it interesting because I began to notice the conflicts within Jair, who is a unique individual, a character from my city. Without much thought, I decided to lend a hand with the music videos. And it was like a whirlwind. I thought things couldn’t end there; I had to tell this story. I talked to my partner and spoke with my production team on the same day. Truly, that afternoon, I already had a movie in my mind. And when something like that happens, I dive in. I started convincing people, and within a week, I assembled the entire team I’d been working with for four years on this project.

In other words, two weeks after the first conversation with Mr. Jair, we were shooting the music videos, and by the third week, we were already filming the movie. The start of filming also coincided with the carnival season, a time when they were very active. We shot intensely for five days. Although my original idea was to make a short film, when filming ended, I felt that this had enough substance to become a feature-length film. We applied for funding from the DAFO fund of the Ministry of Culture, and we won. But the following year, the pandemic began. That changed everything. Because even though we had the funds, there were many things we needed help to do. We couldn’t even buy the equipment. We attempted to film twice; the team came to Iquitos, but we evacuated them. Some team members fell ill at a time when there were no vaccines.

It was truly challenging to make this film, especially because Iquitos was one of the hardest-hit areas in the country due to the pandemic. And Los Wembler’s were caught up in that whirlwind. Before that, the city was already going through a dengue hospital crisis, and the entire healthcare system was overwhelmed. The pandemic made it much worse. The second wave took Alberto, the guitarist of Los Wembler’s, and two other Sánchez brothers, who, although no longer active musically, were founding members of the band.

Music video for the song “Icaro del Amor,” directed by Luis Chumbe

How did you complete the film in such a complex and painful context?

I started filming with the joy of having five brothers making music for fifty years. And suddenly, there were only two. In reality, I hadn’t recorded much. It was a critical moment for the project, but also for us personally because documentary filmmaking connects with life. The people who passed away were my friends, with whom I had shared a lot. It was a moment of great pain, a loss for everyone. However, life continued. Los Wembler’s continued and still give their all. The film reflects what happened to us in these four years.

As I mentioned, I had a different idea for the film at the beginning. They had many plans; they were going to return to Europe, and they had projected six months of touring. They had achieved something significant in their lives. But the pandemic put an end to all of that. However, they never stopped working. They are musicians, their children are musicians, and their grandchildren are musicians. The peculiarity of Los Wembler’s, which sets them apart from other cumbia groups like Los Destellos or Los Mirlos, is that they are a family clan. The strength of the film also comes from this because it focuses on that legacy. The band is led by two patriarchs who manage their families according to Iquitos’ customs. In essence, the patriarchs contribute significantly to the sense of community experienced in the jungle. The Sánchez brothers are great for that; they are authentic Loretans, genuine Charapa musicians. And their children continue that legacy.

Videoclip of the song “Lamento selvático”, directed by Luis Chumbe.

But the main difficulty was that Alberto Sánchez, the lead guitarist of Los Wembler’s, was no longer with us. He passed away during filming. And Alberto was truly the genius of this group. So, replacing him seemed impossible. Eventually, Jair’s eldest son took up the mantle, but it’s still a tremendous challenge for him. The truth is that all the footage I captured with Alberto during his lifetime took on a special significance for the project because he was, in fact, the direct author of the Amazonian sound that was fading away. As a result, the film began to take on a different meaning. I am very intuitive; when I work on a project, I see in which direction life is moving, and based on that, I piece things together, always with respect for the situation because these are real people who are opening up about their intimate lives, their problems, and their dreams.

Four years have passed. We resumed filming when we could. Many things happened to get to this point where Los Wembler’s managed to prevail. This film embodies everything that occurred, how there was a difficult period when they faded away, but then there was a rebirth. In that sense, it’s a very honest film. And they are very likable characters, which is part of the movie’s appeal. Many older people are in “Amazonian Sound,” both the musicians and their fans. The presence of their children becomes stronger towards the end as if to pass the torch to what they are now.

So, they are happy with the film, and I am too. I think it contributes to how we tell stories and make films from the Amazon, which will remain for Los Wembler’s and the city because it’s also a tribute to Iquitos and our way of life. The photographic approach stems from our local customs and who we are there.

Could we talk a bit more about that approach?

As I mentioned, we had several setbacks during filming, including finding moments to shoot and what equipment to use since we couldn’t afford to buy much material during the pandemic. So, we started filming with whatever was at hand, gathering material from various sources, and then there were intense filming moments with the entire production team.

The idea was not to make a polished film. We wanted a lot of movement for the film to feel alive, to convey the city’s rhythm, the pace of the moto-taxis, the rhythm of madness, and the rhythm of music. That’s how they are; they are super energetic uncles who are always busy with many things. That’s how the photographic approach was born.

There are many shots of the river; we filmed from canoes. We also used drones because it’s a city that coexists with rivers and the jungle, and that has to be seen from above. I wanted to reflect a lot of that strong identity in the characters, the city, and, I dare say, in myself as well. There is a very Amazonian language in this film, through how the protagonists speak, with their double meanings, and how it was filmed. It’s a funny, sad film and connects a lot with Amazonians. Let’s see how it is received in Lima.