The Artist Gardener and His Coca Plants

Colombian artist Wilson Díaz has been working with coca plants for 27 years. His work includes live coca plants, seeds containing possible plants, dyes, and charcoals made from fruit or wood, and still and moving images depicting the everyday life of this plant. He is an artist gardener who has brought to light the frictions associated with the plant, its contradictions, prejudices, and potentialities.

By Marcela Vallejo

In 2008, in Colombia, Álvaro Uribe’s government launched the advertising campaign “Don’t Cultivate the Plant That Kills.” In radio and television ads, the state propaganda claimed, “Coca, poppy, and marijuana are plants that kill.” Two years later, the indigenous movement, represented by Fabiola Piñacué, won a lawsuit against the state because the campaign implied stigmatizing indigenous plants and cultural traditions. However, the message resonated with the Colombian population. Only now has a campaign been created to refute that idea and propose the slogan “The plant doesn’t kill.”

This campaign represented a government that lasted two presidential terms and devoted much of its budget and energy to the so-called ‘war on drugs.’ During this government, the dividing line between the counterinsurgency and the fight against drug trafficking was blurred, and it was during this period that the guerrillas lost their recognition as rebels and began to be labeled as narcoterrorists.

In this context, anyone who opposed the government criticized it, or sympathized with other political currents was declared an enemy. That, of course, included questioning the national drug policy. In that context, creating a work like “Cuarentena” – an installation by Wilson Díaz exhibited in the showcase of Lugar a dudas in Cali – meant taking a stance. In August 2008, the Colombian artist exchanged emails with Amy Franceschini of the Future Farmers collective. Wilson had documented coca plants used in gardens in Cali for ornamental and space division purposes. Throughout his observations, he identified that three pests affected the plants. He then requested the help of the Future Farmers collective to think about how to protect the surviving plants.

“Cuarentena” consisted of five coca shrubs planted in a large glass container and two paper lithographs with the artists’ email exchange. This exchange was the initial thread of new collaborations that led to the project “The Movement of the Liberation of the Coca Plant.” With this work, Díaz was openly advocating for the coca plant as a living being with the right to exist and do so in dignified conditions. Talking about the pests that plagued it meant treating coca as any other plant and distancing oneself from the demonizing positions the state was promoting at the time.

It wasn’t the first time Wilson did it. Since 1996, the artist has worked, among other things, with coca plants in his works. He is an artist who is also a gardener, who has worked with plants in their materiality and as raw materials to produce materials; his works on the subject address both war, persecution, the frontal attack on nature and some human beings, as well as the defense of the plant in more everyday and intimate terms.

He began working with coca in 1996 with “Untitled,” an installation that included coca plants, a diary, and a painting of an image of the youth group Menudo. The following year, he created “Fallas de origen,” another installation that featured a red house (reminiscent of the Davivienda bank logo), a garden with 100 coca seedlings, and two videos displayed in the house’s windows.

Since then, he has performed acts in which he consumes the seeds (“Vientre Alquilado,” 2000), plants and cares for them (“Gardener,” 2004), created installations incorporating plants, or produced other works using materials derived from them. He has exhibited photos of gardens in Cali where the plant serves ornamental purposes (“Jardines de coca en Cali,” 2003).

He has created, through interviews and research, an instructional guide that explains how to prepare a kilogram of cocaine (titled “Cómo hacer un kilo de cocaína de alta pureza en 20 pasos aprovechando de la mejor manera los insumos utilizados,” curated by Hans Ulrich Obrist, 2002). He has also cultivated the plant and worked on its cultivation alongside expert gardeners (Agro Poética, 2013). The list is extensive.

Wilson Díaz is a highly active artist with a body of work that spans drawing, painting, performance, installation, video, and photography. He has worked independently, in collaboration with other artists, and with his collective, Helena Producciones. His work has evolved, and it is so extensive that it allows for exploring multiple avenues of dialogue and interpretation. In this interview, we focus on those works related to the coca leaf, a central plant in his art.

“The proposed attack in so many ways and execution, as an attempt to eliminate coca in Colombian territory, implied not only the combat and eradication of that plant but above all was an attack on nature and the inhabitants of the territory, endangering culture, food security, and health, among other things.”

Your work has been constant and diligent since you began. You have done performances, installations, and paintings. At what point in your artistic career do you place the starting point for working with plants, especially with coca leaves?

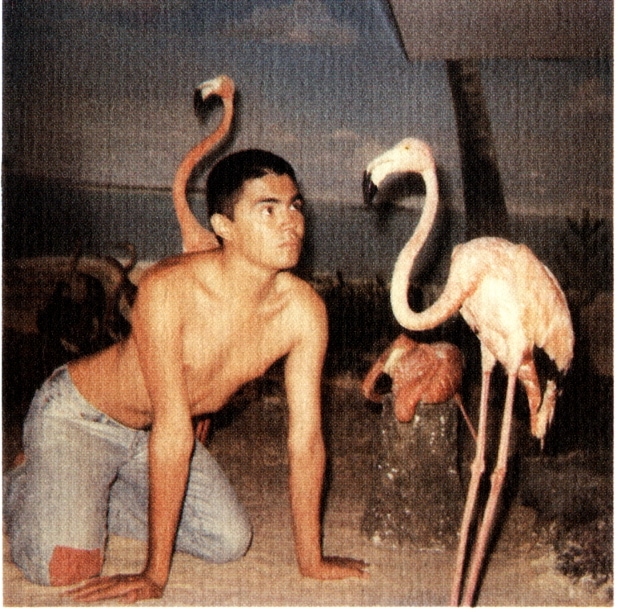

There are two works from the mid-1990s that I consider fundamental. In 1995, I created “No salgas al jardín,” an installation at the Santa Fe gallery concerning a Natural History museum located in the same building on the same floor as the gallery. I connected my work to that museum, which was on the verge of closure due to its evident decline. I used the museum’s dioramas as a set to be photographed in various actions by Víctor Robledo. I developed the idea of transforming the Santa Fe gallery into a place to view a single, giant diorama. To achieve this, I removed the panels covering the windows, creating a 50-meter curved “screen” that allowed a view from the gallery to the park. It was like a Cinerama screen to traverse. I attached a series of 100 cut-outs, drawn, and painted birds on metal sheets to the nearby and distant trees. That was an important step toward considering nature as a central theme.

The other work from 1995 was also at the V National Young Artists’ Art Exhibition at the Santa Fe Gallery. It was an installation in which I used avocado seeds, paint, and matchboxes intervened with drawings and collages. Avocado has been another essential plant as a material resource; I have primarily used it to prepare indelible ink, drawing from the popular and rural use of avocado pits as a source of pigment for marking clothing.

And when did you start using the coca plant in your works?

In 1996, I traveled to the United States due to an award from the VII Regional Artists’ Exhibition organized by Colcultura. It was my first trip abroad, an important formative experience that helped me understand certain things related to exclusion and prejudice. It’s important to note that this trip occurred in a challenging context: it was a shocking year for Colombians. In 1996, the U.S. government revoked the visa of Colombia’s president at the time, Ernesto Samper, to pressure him due to his government’s alleged connection to drug trafficking. That same year, the U.S. government decertified Colombia for, according to them, not cooperating with Washington in the fight against narcotics.

This experience made me realize that extremes can be part of unity, not separated as we typically perceive them. On the surface, prejudice seemed to be separate from that other place from which accusations and judgments are made. I thought the line between the object that gives rise to prejudice out of fear and contempt and the one who points and accuses worked in only one direction. Later, I understood that it could be traversed in different directions beyond what was proposed by those who initially held power. In other words, this not only suggests a place of discord but also a place of negotiation, action, and potentiality. With these ideas, I began to work on problematic issues that led me to advance and arrive at new places and ideas.

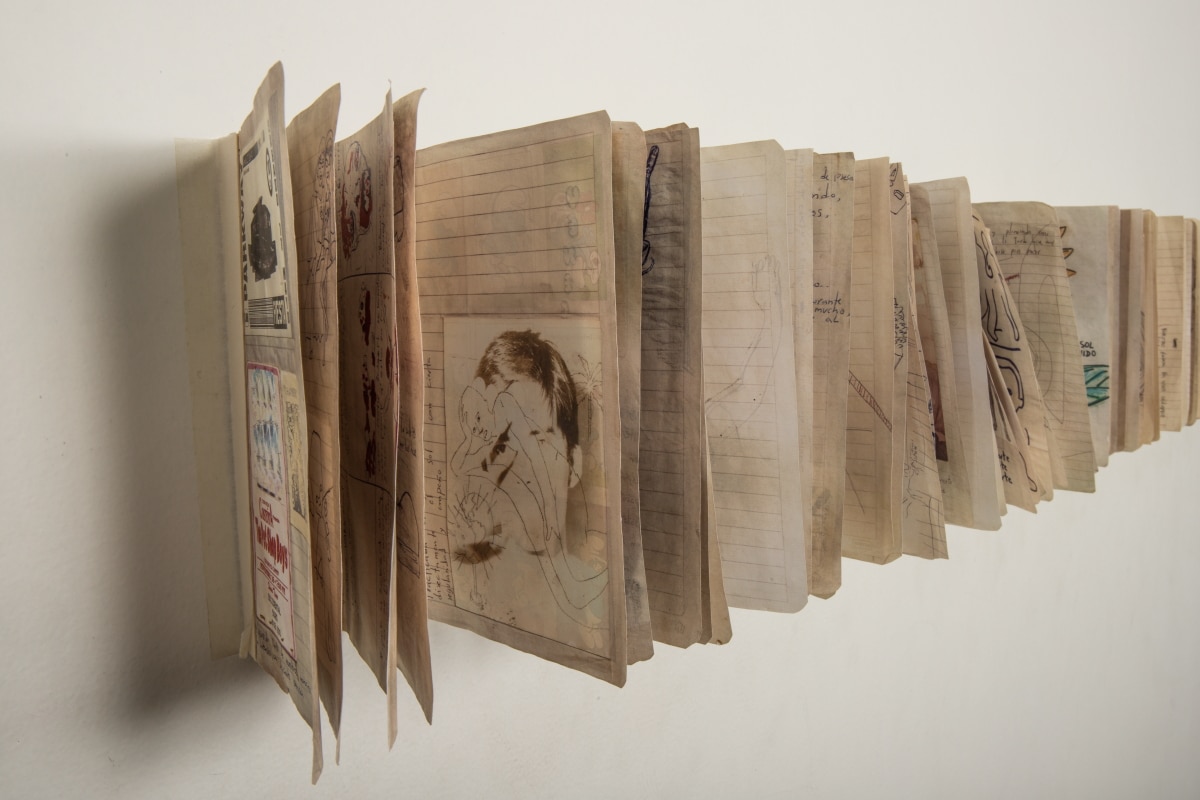

With all of this, in 1996, I presented the installation “Sin Título,” which includes coca plants, at the VI Young Artists’ Art Exhibition. The installation consists of an acrylic painting on cordovan leather of the well-known musical group Menudo, a kind of fictitious diary drawn and handwritten on sheets of paper, installed on the wall to be manipulated, a coca bush planted in a pot, and several small coca plants planted in bags. I sought references from the youth universe, which also allowed for an anachronistic and obsolete effect connected to a sarcastic critique aimed at the society of that time.

During that period, it became evident to those who wanted to see that the proposed attack, in so many ways and in execution, as an attempt to eliminate coca in Colombian territory, implied not only the combat and eradication of that plant but above all was an attack on nature and the inhabitants of the territory, endangering culture, food security, and health, among other things.

Regarding this dual path of prejudice, what do you find when you return along the line that marks the accusation?

I realized that I could directly address some issues without any shame as an observer and not as a person with the power to make decisions and effect change in that reality. At that moment, as a society, we were confronted with a reality that overwhelmed us, trapping us in many injustices.

I decided that I could speak about war, drug trafficking, and other common issues with distance. To the extent that we have had no choice in the matter, that no one has asked us whether we want to participate or not in a war in a context shaped by propaganda and falsehoods. So, why not participate and attend to the war as if it were a spectacle, as presented by the media and propaganda in a constant déjà vu where history repeats itself?

A criticism that has been leveled at a portion of Colombia’s social sciences is its focus on war until the 2000s. That is, both from the perspective of the so-called “violentologists” who did important work in narrating the war and other social scientists who conducted research without even mentioning violence. From what I hear from you, things were different in art, and you experienced a kind of liberation during the 1990s.

There’s an interesting aspect here: in the visual arts in the 1980s, almost no one talked about drug trafficking, even though it had been a fundamental aspect of this reality since the 1970s, which is quite significant. On the contrary, some Colombian filmmakers and other creative disciplines did address it in their works. However, the issue of conflict and violence was critical in the narrative and creation in the visual arts in this country and can be traced back to the first half of the 20th century.

All these issues began to appear with great force after the proclamation of the Constitution of 1991. It was a watershed moment that allowed Colombian society to recognize itself and see itself in an unprecedented way.

You talk about viewing war and drug trafficking as a spectacle, but you have also mentioned the coca gardens in the houses of Cali, the plant as an ornament. In other words, there is also a daily relationship.

I often find that having a problematic motive to participate stimulates me, but so does understanding the context and uniqueness of our history and time about and beyond nations. For example, in 2000, when I went to the demilitarized zone in El Caguán, I was interested in the relationship between the vallenato music group Julián Conrado and his comrades with the ideas and tactics of the Russian Productivist artistic avant-garde, where all the cultural production in society, including art, graphic design, industrial design, architecture, fashion, cinema, and music, was used as a space to convey ideological content. This perspective, in a way, allowed me to see the history of the war in Colombia concerning paradigmatic events in the history of conflict, post-conflict, and utopia.

When I went there, I made a video called “Los Rebeldes del Sur” and took some photos that I only showed in 2002, at the beginning of Álvaro Uribe’s first presidency (2002-2010). I decided to exhibit this project because different conditions began to emerge at that time. For example, during the previous government of Andrés Pastrana (president 1998-2002), the guerrillas seemed like showbiz characters. I saw a press release in a well-known magazine about the novelty of a commander’s satellite phone or the demilitarized zone and its thematic meetings. I attended one in 2000 dedicated to culture and employment. At certain moments, the narrative surrounding it behaved like a kind of reality TV broadcast nationwide, which was also in line with the emergence of reality shows. These types of information and entertainment formats were becoming so important in global mass communication platforms.

During Uribe’s government, the narrative changed, and the story took a different direction. At that point, I found it interesting to show this installation composed of four videos and several photographs in the project titled “Long live the new flesh,” which was presented at the Valenzuela & Klenner Gallery in 2002. Exhibiting this project at that moment made me think of myself as a political artist, albeit very ironically, because I didn’t have a solid political education. Still, I belong to a very disillusioned and skeptical generation. I was, to some extent, responding to the models of the artist and political art that had been defined in Colombia.

During that time, you continued working with coca. How does this look regarding not apologizing for your work with the plant and the drug?

In that same vein, I embarked on a project titled “Cómo hacer un kilo de cocaína de alta pureza en 20 pasos aprovechando de la mejor manera los insumos utilizados,” curated by Hans Ulrich Obrist (2002). It was a text-based art piece within the framework of Obrist’s curatorial project, and it was published in “Do It.” To create it, I interviewed various individuals to find out how this formula of German origin, which allows for the production of coca paste and cocaine crystals, had evolved in the hands of laboratory operators out of necessity or other factors due to the scarcity or unavailability of the ingredients specified in the formula.

When the artwork is transferred to an online publication or a printed book, as is the case with “Do it,” this piece, to say it with sarcasm, can only be produced in specific geographic, political, and economic territories where there is cheap labor to exploit, and where it is possible to clear a significant amount of jungle to produce the 60 arrobas of coca leaves needed to make one kilogram of cocaine. It’s a piece of reality presented directly.

You had been thinking about the political role of art and the Soviet Productivist movement, and you created some works with political gestures in mind. But then, can an artist have a political role, or does it not matter?

I don’t think this applies equally to everyone. I believe the artist must exercise the freedom to create, express, and even abstain from responsibility. In that sense, whether or not an artist becomes political is entirely their choice. I’m very interested in the oscillation between the politics of the everyday, the personal, the intimate, and the politics of participation and citizenship.

I am currently in a dilemma regarding my work related to the coca plant. When I began working with coca, I always had in mind the actions and exercises of citizenship by indigenous communities, as well as their culture and practices. I also considered my limits when proposing works related to the coca plant in history and as a material for my art. So, I set some boundaries, thinking about what I could speak about regarding coca without invading a territory.

Thus, one input was the colonial history written in the language of Spanish invaders, as well as the writings and authors I’ve researched. Another input was the coca plant being used as a garden plant in Cali, where I live. I developed a practice as an amateur gardener caring for coca plants in urban gardens. Through a photographic series in 2003, I documented the “Jardines de coca en Cali” and the recovery of remnants of the plant when bushes had been removed over the past twenty years in various locations in the city. I produced pigment from the pulp of the plant’s seeds, which I’ve used in drawings since 2003, and charcoal from wood for drawing. I’ve used the living plant in my artworks carried out actions and gestures using these materials. Still, I have documented these narratives using more traditional materials like acrylic paint on canvas.

It is important that the artist exercises with responsibility the freedom to create, speak, express, and even not to create. In that sense, the artist will be political or not as they please. I am very interested in the oscillation between the politics of the every day, the personal, the intimate, and the politics of participation and citizenship.

In ‘Fallas de Origen (1997), one of your installations, there is a little red house (like the one from Davivienda), and in its windows, videos are playing. In front of the house, as if it were its front yard, there are 100 coca plants enclosed by colorful painted stones. This installation underwent some changes when you exhibited it outside the country.

I first presented it in 1997 in Cali at the La Tertulia Museum during the Regional Artists Salon. I presented it at the National Artists Salon in Bogotá one year later. The Argentine curator Carlos Basualdo, one of the judges who awarded this work as one of the three winners at the National Salon, invited me to exhibit it in an exhibition he curated titled ‘De la Adversidad Vivimos’ at the Museum of Modern Art in Paris in 2001.

The Museum sent me an email to my Yahoo account stating that neither the museum authorities nor the French authorities would allow me to bring the coca plants to Paris and the Museum. They also said there was a similar but different plant called Skimmia japonica, which they claimed looked the same, and they proposed replacing the 100 coca plants in the installation with those from France.

Something that concerned artists when the internet was not as important and widespread as it is now is to exhibit work in a distant country. It needs contextualization. That applied to both those leaving this country and foreigners arriving here. The solution was to accompany the work with a text that explains and contextualizes it or with a live presentation explaining it.

In my case in France, the Museum of Modern Art in Paris contextualized my work by writing this email. I set up my installation with the 100 bags filled with soil, of course, without the plants, and next to it on the wall, I affixed a printout of the email they sent. That email also allowed me to bring up something that had already happened to me the previous year during an artist residency on the island of Curaçao.”

Does the context also imply some limits?

Here, I revisit the story of what happened in Curaçao. In 2000, I participated in the Watamula Artist Workshop, a residency for artists of the Triangle Network format. I was invited to create a work related to nature and a specific site, and the organizers didn’t ask for a written project. So, I developed my project “Rented Belly,” which consisted of the following performative action: before my trip to Curaçao, I swallowed 30 coca seeds in Cali, then took the plane journey, and upon arrival, I sought out a suitable place and defecated in an overgrown area filled with herbs and plants.

It was a significant action. At that time, in conversations between Colombia and the United States, it was not accepted that there was a relationship between production and consumption. In debates, there were statements like: “Why not drop a bomb on Medellín?” or “Why not spread the Fusarium oxysporum fungus over rural and jungle areas of Colombia?” Despite the ongoing use of Glyphosate or Roundup Ultra since the 1990s.

When I arrived in Curaçao, the work was almost completed. I asked the organizers for a cameraperson who would also take photographs; this way, the action was documented. We gathered with the invited artists and event organizers on the second or third day. They subjected me to a kind of trial, and one of the questions I remember was, “Why are you bringing your Colombian problems here?” along with other questions and statements of a similar nature. Ultimately, they concluded that what I had done couldn’t be known, and I had to commit to destroying everything. I was forced to accept, and the documentation of my work was destroyed.

A day later, I met with their lawyer, who explained that while what I had done was not illegal, it was very delicate because in Papiamento, the local language, there was no distinction between the words “coca” and “cocaine.” Additionally, Curaçao was one of the entry routes to Europe for people carrying cocaine. This project was initially planned for several countries that year, but it was only executed once.

At the end of the residency in Curaçao, there was an exhibition. I shared this story with journalist Nel Casimiri, who wrote an article in the local newspaper; that’s how this work was documented.

These experiences led me to consider the importance of considering contexts and accepting friction, understanding the meeting and misalignment in the current state of artworks. Being flexible and not assuming that the artist finishes and closes “the works,” but understanding that when they are exhibited, they transform, and there is still much to learn from them, both in the studio, during their creation, and in their exhibition and circulation.