In September 2017, Hurricane María destroyed Puerto Rico. It is estimated that three thousand people died. It was the worst natural disaster registered on those islands plus the subsequent laziness of the authorities dealing with the catastrophe. The father of the photographer Gabriela Báez spent a year without light, without work and with depression. Since he comitted suicide, she seeks to discover who her father really was and –above all– who is herself.

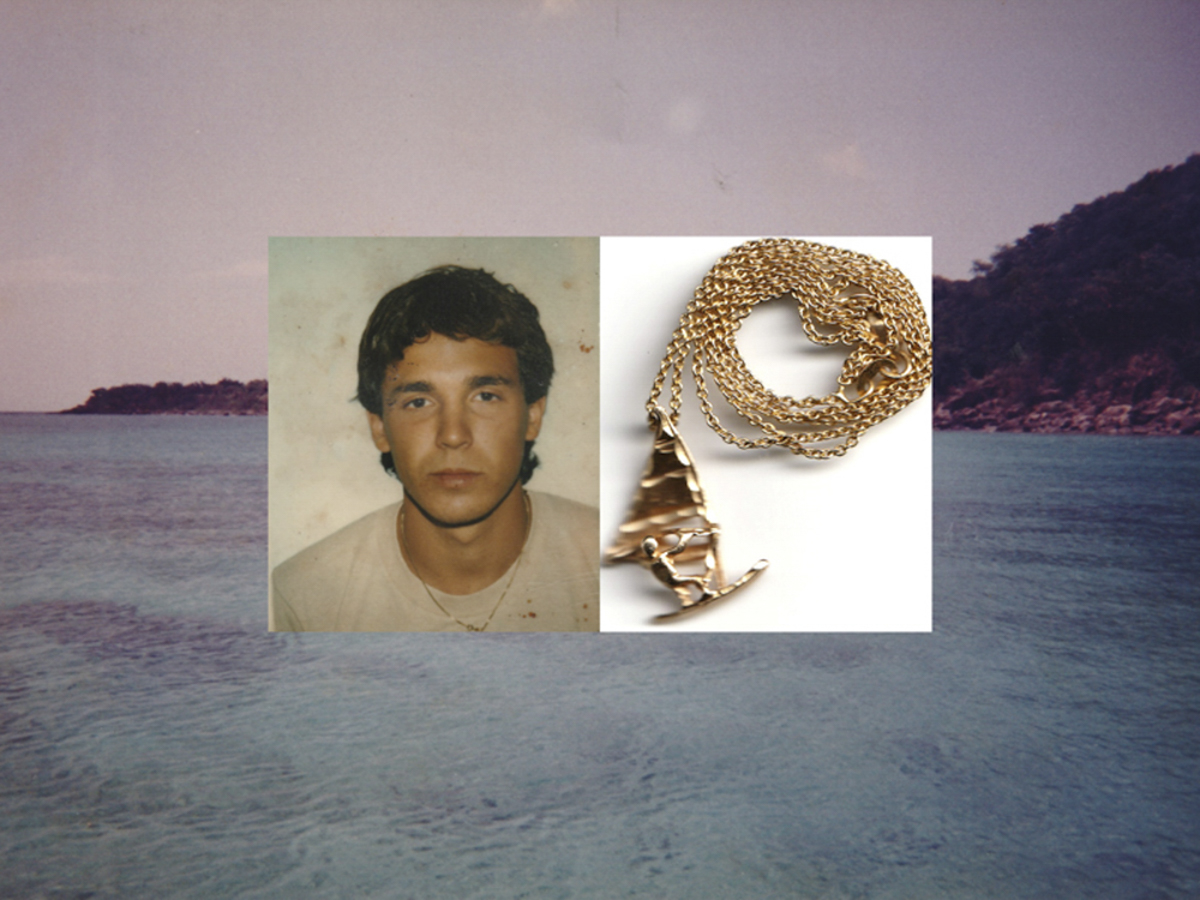

“My dad’s death was a reflection: both of us were experiencing a depression simultaneously, we even took the same medication” Gabriela says. As his body was burned because there was a waiting list in the morgue, Gabriela decided to dive into the family memory through the objects. She didn’t know if she was going to be able to keep them or if another natural disaster was going to take them away from one day to the next. So, she photographed a picture frame with a photo of the two of them and a border with summer motifs, a shirt, several paperweights. Her dad was very fond of paperweights.

Later she started to intervene the photos with a thread, as a form to “bring them to present”. Or, perhaps, as a way to ask him. “I can’t confront him, I can’t talk to him about how he acted”, she says. She also seeks for answers in the water, on the beaches, in the sand. That is why the project is called Ojalá nos encontremos en el mar.

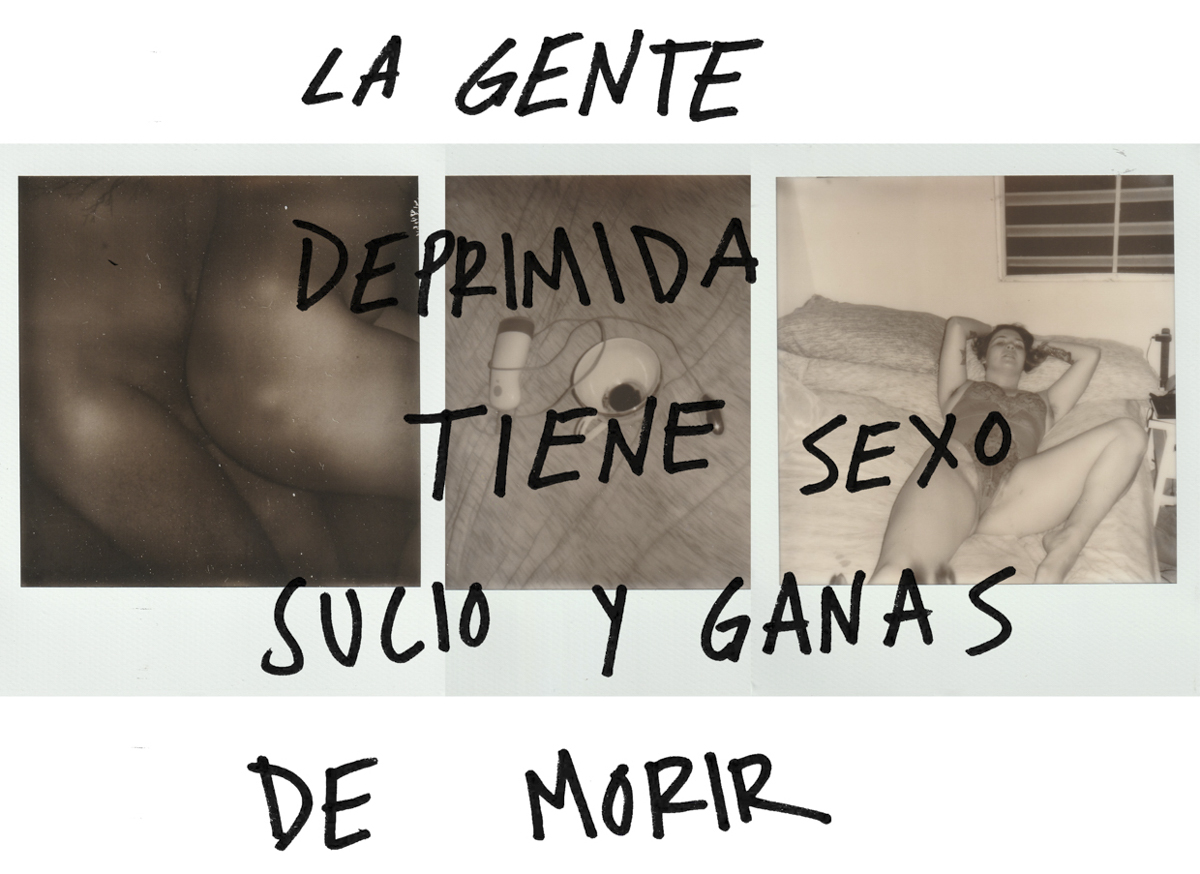

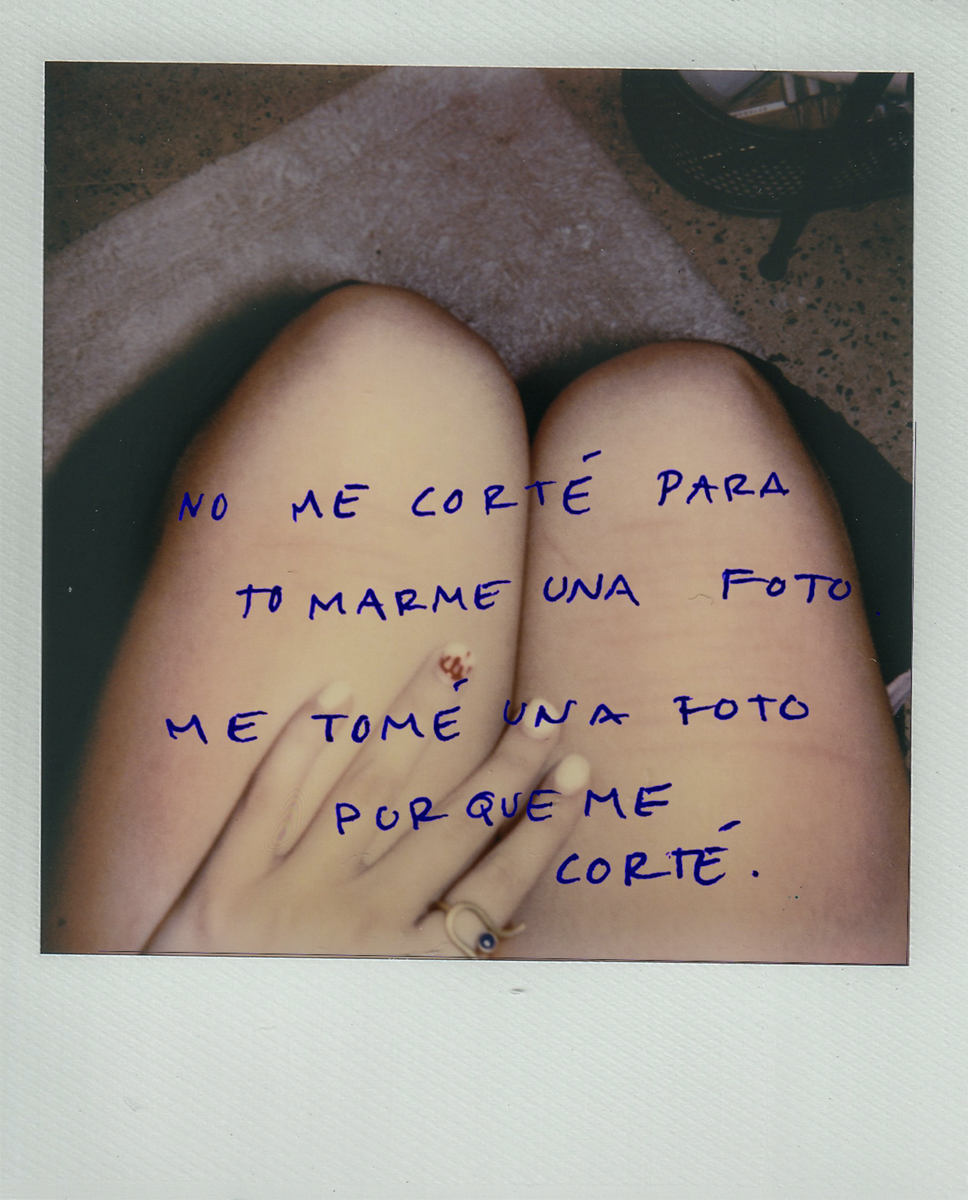

While she thinks she is reaching the end of the project about her father, Gabriela has two more in process. One is called La gente deprimida tiene sexo sucio y ganas de morir and she defines the common thread: all of her projects have to do with trauma. In this case, she challenges the idea that depressed people do not have sexual desire. “I looked for sex so I wouldn’t think about my problems and I started to understand sexuality as a tool for healing and empowerment”, she says. In the second ongoing project, Island putxs, Gabriela explores identity, genre and sexual work in the middle of pandemic.

“Everything is dark, I think I’m dead. I see my body from the outside.

My back is fractured, broken in pieces. I cry and scream resisting the worst sensations I’ve felt in my life, realizing that my suicide attempt had failed.

I wake up with a gasp. Since then I feel the same pain beyond my dreams”.

How was the process of Ojalá nos encontremos en el mar?

Ten months after Hurracane María, my father comitts suicide. At that point, I realized the impact of this natural disaster on the island on an individual level. I could see the destruction around me, I spent a lot of months without light and without work, but it was not until that moment that I felt it in the magnitude of when they spoke on the news. So, the death of my Father was a mirror, a reflection: I realized that both of us, my dad and myself, were experiencing depression simultaneously. We even take the same medications. So when he commits suicide it was a shock. Not only because I lost my father, but because I saw myself reflected in that possibility. I realized that if I did not work in my mental health and what I felt very deeply about my childhood, my adolescence and the hurricane, I could end up like this too, I could make that decision. It was during this process of healing, searching and uncertainty, that I went towards the camera and started working on this project.

I started in October 2018. The first thing I did was to portray his objects, the ones that were given to me after the funeral. It was the most obvious thing to do at the moment. There was no physical body, not even a grave. What was left of him were his objects. For the number of bodies that were waiting in forensic science, the fastest process after the disaster was cremation and my family opted for that. The ashes are in the house where my father, my stepmother and my younger brother lived. I feel that it is also very different to go to see a vase where the ashes are to go to a cemetery, to visit a grave. That is why there was no body and the closest thing to it was the frame of a portrait that had candles and he and I are in front of a pool. What was left was a Pink Floyd shirt, photo albums, a paperweight… he was very fond of paperweights, there were like three of those. They were like decoration materials that he had in his office, in his house. That was my first instinct, to portray those things, as a way to preserve it. I didn’t know if I was going to keep those objects or if another natural disaster was going to happen and I was going to lose them.

I started looking at the stock photos. My family had a lot of photo albums, of houses full of photos. As I watched them, I felt like I wanted to bring them to the present in some way. That’s when I start to intervene with thread. Initially it was an experimentation, I really didn’t have a very concrete reason why I wanted to intervene in this file. I felt many emotions and wanted to capture them in some way in the images that I was seeing. I began to sew the images, to intervene with the needle, to break them. The project stayed there for about a year.

I think life and its abyss gave may father a reason, Hurricane María gave him a noose, and now Puerto Rico is his tomb.

I started looking at the family album. My family had a lot of photo albums, of houses full of photos. As I watched them, I felt like I wanted to bring them to the present in some way. That’s when I start to intervene with thread. Initially it was an experimentation, I really didn’t have a very concrete reason why I wanted to intervene in those photos. I felt many emotions and wanted to capture them in some way in the images that I was seeing. I began to sew the images, to intervene with the needle, to break them. The project stayed there for about a year.

The photographs pushed me to confront parts of my grief that I did not want to accept. I gradually realized that I had not had photos with my father in the last five years. Then the project begins to change. It was hard for me to break with the idea that my father was a saint, he was innocent, he was the best person in the world. Perhaps because I was not ready to confront that he was a human being just like me, that he had his own traumas and that he also did not know how to deal with me, with my process of growing up, with my process of being a teenager, with my own explorations. For him, as a father, these things were difficult for him. I had to accept that, that we had a broken relationship, that it was difficult, that we weren’t always together, that was what led me to the next step.

I accepted that it was not a common duel, either. I had to deal with the political side of my father’s death, which was the context of the “post” hurricane that destroyed the island. The management, by the government, was negligent. Here people were allowed to die, everything possible was done so that the people who were left alive in Puerto Rico left the country. Or they simply did not attend to the situation, period. Understanding those complexities within my grief was a step in being able to begin to heal and access other deeper levels within this project. Last year I was writing and looking for spaces where we used to share and it became more of a meditation, a project less about my father and more about my process of accepting the death of my father. All the traumas that I had in store woke up. It forced me to confront myself and that has been the process of this last year.

That’s what my psychologists and psychiatrists say, that it will always be there even if I don’t want it. I don’t know if that is true. If I could talk to spirits, could I resolve my issues with my father?

What happened since then?

More images of landscapes began to appear, from a search. A word that resonated a lot with me was “magic”, a spiritual quest to connect with what was not seen and what was felt. A process of bringing the unconscious into consciousness began. I have been recreating dreams in images. It was that search of wanting to go deeper and visualize the unconscious within this project.

This second stage was to be able to verbalize what I was feeling. The process of creating images comes naturally to me and I took the camera everywhere and found images that were related. But the process of putting this into words or pictures or doing something on paper was what changed my project. I cannot separate the text from the images. It is in the editing process, there are a hundred pages that I wrote by hand, we are editing. They are going to be part of a book.

What was your dad like?

He had his own business, he made retirement plans. He liked windsurfing, playing tennis. He was quite a physically active person. He loved the beach and the sea, that’s where the title of the project comes from. Literally, many times I went to the sea to look for answers that I could not find. That space of wanting to discover other beaches, other seas, is part of my search for my father and the memories I have with him. He was a person with access to resources: my father had the opportunity to go to therapy, to receive medication for depression. Part of this has been admitting that I don’t know my father very much, I know what he wanted to teach me: the adventurous side of him, of wanting to play sports, his musical side. The reality is that, on an emotional level, I don’t know my father. So, from where I saw him, he was an extremely balanced person, with resources and with a great support system. My stepmother and he had a beautiful relationship, there was my younger brother. From what he looked like, he seemed to have all the resources to stay healthy.

But the hurricane was more than the hurricane, because it goes beyond the day of the storm, it is what comes after. Being without electricity for more than six months, not being able to work, having to buy a power plant, which continued to break down. Then not being able to go to his office. It was those kinds of things that were overcoming and increasing his anxiety and his depression. I believe that, assuming from what I have learned from myself this past year, the hurricane and what happened after that aroused traumas and problems in him that he had not been able to work with until then. It was the last straw.

I was learning a lot about the process, about how trauma is experienced, I assumed things about the process from my father but nobody has told me about it, other than my mother. She has told me very nice things about him and strong things to accept, too. Her as his partner at that time and me as his daughter talking about this after his death… One of the things that has made me stronger is that I cannot confront him, I cannot talk to him about how he acted, I cannot talk to him about our relationship. As I receive information from my mother or that I discover, I find that I have no solution to that, I have no way to answer those questions.

How did your relationship with photography begin?

I started making images in 2017 before the hurricane. That year many demonstrations began against the Fiscal Control Board, which was signed by Barack Obama and forms an entity that controls the economic decisions of the country. Puerto Rico is in a debt of millions of dollars and the Board’s purpose is to be able to pay that debt at the cost of taking austerity measures for education, health, housing, and the country’s infrastructure, for everything. At the cost of quality of life and to pay off millionaire bondholders on Wall Street.

In 2017 there was a wave of protests against the Board and all the campuses of the Universidad de Puerto Rico (the only public one) were on strike for three months. At that time I started taking photos of the demonstrations because I understood that the press, at the local level, was demonizing the protesters. I was also a protester and I felt quite indignant when I saw the representations that were made. I said: “I have the perspective of a protester, I’m going to take the photos.” Since then, my approach has changed quite a bit. Before it was very broad: the country’s problems at the macro level. Little by little, after my father’s experience, it was changing to focus on myself and my identities, in wanting to understand mental health, in wanting to understand my sexuality and my gender, those are the issues that I have been focusing on.

Is that where your other project was born, La gente deprimida tiene sexo sucio y ganas de morir (Depressed people have dirty sex and want to die)?

It arose a year after starting my father’s project, it began in August 2019. During the process of experiencing grief, of questioning myself, it was a process of wanting to know who I am. The death of my father made me realize that I lived automatically, there was no deep thought about who Gabriela Báez is, what she wants. That’s where that project comes from.

I realized that depressed people are thought to be asexual, and I felt the opposite: I was seeking sex so as not to think about my problems or to feel better after I had been processing my problems. I began to understand sex and sexuality as a tool for healing and empowerment. All my projects have to do with trauma.

I also do this project with my current partner, we have an open relationship, we share with more than one partner. That produced a lot of insecurities that I was not aware of and forced me to work on them, to be able to support myself and not be there putting my emotional burden on my partner, which is what is usually done in a monogamous couple. It was learning to have a relationship with myself, with my partner and with other people. Right now that project is in a process of transformation, that I feel that my father’s project is closing or is turning into something else, I focus more on this project because right now I have questions about gender and sexuality.