Diego Mondaca remembers the familiar meetings when he was a child, in the 80’s. He remembers, punctually, that in a determined moment the males of the family stood aside and always (always) began to talk about the Chaco War that faced Bolivia and Paraguay between 1932 and 1935. First, the talk was fun: they told unusual anecdotes, such as bathing in kerosene or drinking urine. But, after a while, their bodies began to remember and they all went into a silent cry.

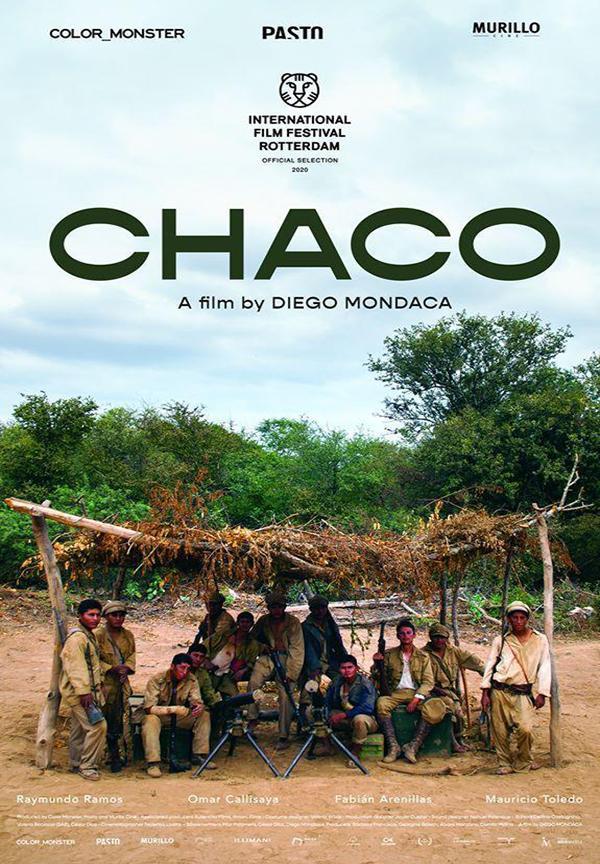

From that silence was born Chaco, the film in which Bolivian filmmaker Diego Mondaca questions the official patriotic account of that war in which “Bolivia lost the sea”. Did Bolivia need to go to that war? Why did they go with so little knowledge of the enemy? Why are there statues that remember the whites who fought and the Indians died without anyone caring about their names? Why were the only images that exist of the war taken by white men and portray the Indians as ‘freaks’?

For the documentary filmmaker Mondaca, some of the elements he shows in that film are a continuum in Bolivian history and reach the present day. Still, for example, in the army they laugh at the young people who arrive without speaking completely perfect Spanish. “We deny Aymara, Quechua, we are denying a culture, a memory, a language, we are working to eliminate ourselves,” he says.

Mondaca studied at the International Film and TV School of Cuba. He is a director, screenwriter, producer. With La Chirola (a short film in which a former Bolivian guerrilla recalls his experiences in prison) he won international awards at festivals around the world. He completed his postgraduate studies on a fellowship at the Filmakademie Baden Württemberg. In 2011 he presented his documentary Ciudadela, which tells daily stories inside the San Pedro prison (La Paz, Bolivia) without practically showing a single fence. Together with colleagues like Isabel Collazo (Bolivia) or Diego Luque (Chile), Mondaca founded “Cineclubcito”, a project for the dissemination of Latin American cinema.

Is it correct to say that you do political cinema, does that definition work for you?

I claim art as a political exercise. Hence, whether it is a supporter or pamphleteer, I do not do that or defend it. Art is not utilitarian nor should it be for joints. Its role is also so besieged because it always goes against the official, whether what we like or attack us. Our position as artists is clearer to me because of what has happened in Bolivia in recent years. The situation demanded not to position oneself in extreme but to have a position as a citizen and from the profession that you carry. What they want to drag you to is to be in the extremes.

The last five years, in Bolivia, a very important social erosion has been evidenced and that became what was the coup d’état. The conditions were given for right-wing factions, of a fascist nature, to organize and begin to articulate very rare and confusing attack strategies. The government’s responses have also been very confusing.

I returned to Bolivia three years ago and I see an improvement in the economy: it is a different country, much more participatory and there are traditional sectors occupied by white elites that began to be penetrated to make it more plural. Beyond that, it is a country that has stopped looking at itself. It has begun to be sweetened by the illusion of progress, a modern country, a country with access, with arrival, we have lost our scale. There has been a disaster. Most of us are scattered in relation to our origin and our cultural memory.

It is not a question only of Bolivia but regional, global. We have all become distracted from the scale on which we act as people. There is a deterioration around: there is Chile, Brazil, Peru, Ecuador. These social crises certainly affect, raise questions, arouse hatred. I think we have been prey to that and also to our mistakes, to our paternalism with ourselves. In the end, that charges us a very heavy bill.

Some of that you worked on Chaco, right?

Yes, I see it in Chaco. I consider the types of human relationships that we establish in very critical moments, crossed by a cultural denial, by a class problem, by a skin color. We are like this because of colonial defects and Judeo-Christian defects that hinder the possibility of having collective campaigns. In function of us (all), as beneficiaries. There is Chaco, set in the war. The Bolivian has the problem of going to the war, of falling apart. Because we don’t know each other, we deny ourselves, we deny Aymara, Quechua, we are denying a culture, a memory, a language, we are working to eliminate ourselves.

That was what the war did. It helps me to put an institution like the army, that annuls you, that annuls everything, completely. It is the State, too, the power struggles and the anguish over impossible victories, for useless campaigns. In a country that didn’t need to go to that war.

It is an invented war, there are a lot of versions but the big story of patriotic pride is that we lost the sea. There had come some German military missions, the Bolivian army was trained by Germans. They had a blind trust and an underestimation of the enemy and the space, a total ignorance. Bolivia did not occupy its territory, it was a young country. It needed a patriotic vindication. It is important to think how we raise flags in a patriotic way without measuring the consequences, which can be very serious. Deep down, those who decided sought to protect their barbecue, rather than a true patriotic convention, that anyway I do not know what it is.

There is always the individual interest. There is always in the foreman. The Indians are forced to go to war to defend a country that turns its back on them, to an unknown territory, to face ghosts. As of today we do not know what Paraguay is like. We do not know what a Paraguayan or Paraguayan is like, we do not have clear commercial or cultural relationships, despite the fact that we share a vast territory. All this that I am telling you that seemed 90 years ago has been repeated in Bolivia, that variegation, that regionalism that has resurfaced now in recent months.

In Chaco you don’t show war; in Chirola or Ciudadela you don’t show the jail, although it’s about that.

I have been developing it. First, more unconscious; now more aware. At heart it is a game. It is playing with the stereotype: presenting it, establishing it and from there breaking it. In Chirola you are with a person who has been in jail but tells you something else. A lot is also playing with curiosity, because of the way we have been raised.

Ciudadela is filmed one hundred percent in prison. People go for curiosity, but it is to know the people who inhabit that space. So, they are chasing the taboo that is established: what is it like, how they traffic, if they kill each other, how they fight, how are the rapes. As if jail were that, hiding that they are not all who are and there are not all who are.

There is also the cruelty of the commercialization of those spaces, for example, jails in the United States or Europe are private. It is because it is a business. Here jails are abandoned because the state does not have a social reintegration policy. It is a film with the landscape of the prison but what you see is the day to day: how they build a community even more efficient than ours, with much sharper limits. The decisions made there are no turning back. If you were wrong, you can go very wrong. If you win, you have a day ahead with two more decisions. This is a bit of the dynamic.

They are entire families that have found a coexistence. For example: I have my partner and four children: society does not give enough space for a woman to work, have a fair salary and be able to support her 3 or 4 children. The man is the one who works and is in jail. Then the woman goes to jail and gets money. The fact that entry is allowed is a social victory and responds to a very complex social need.

It is a thoughtful decision, it is not a silly one. The woman there, with the collaboration of the man, begins to do a small business of meals, empanadas, photocopies. She very silently is pacifying the space of the jail. That is something very difficult to understand. Entering the jail you have the same topography, the same colors, the same faces, the same dynamics that exist in a neighborhood. Your brain is not ready for this and you don’t know it. What you see is the same lady that you have as a neighbor, your same society within a great wall that is the jail.

Another interesting thing is how this social dynamic begins to break down the internal walls. Overcrowding and the force of finding spaces break that panopticon architecture, designed for control. There you realize that life is always being claimed. They go like subdividing, sectorizing, breaking the old walls to be able to make a little room. They undermine the walls to have a kind of bunk.

When we recorded they told us: “We are not going to ask for money, what we need is to build a cell for our companions.” They needed construction material, they provided the labor. So we pass concrete, bricks, roofs. While we were filming, small cells were being built. That was the exchange.

The women and children also go out to look for the merchandise and the school. When they return it is a very hard moment, if you see it from the outside. It is a reality that we do not have to accept but we do have to understand the motives. That injustice is in society, it is not in jail.

In order to understand the clichés and dismantle them, you first have to study them a lot, how was it?

The memory of the Chaco War was written by the most privileged. I strongly vindicate film research, it seems to me something that belongs to the profession. You can find a movie working, says Ignacio Agüero, a great Chilean director. For example, for Chirola I read a lot of psychology, a book by Viktor Frankl (Man’s Search for Meaning). It tells of his experience in concentration camps, where there was a search to find meaning in space. There is also Foucault, Dostoevsky. I am associated with literature, from there I build. It has helped me a lot for the construction of Ciudadela. The human being does not stop being human: they are the same darkness and luminescence.

Ciudadela has been much more complex in that research, I have spoken with many psychologists who explore the human spirit. There are spaces, such as jail or others that have been torture spaces, where terrible fragility is at stake. But that fragility exists because on the other side there is torture. The torturer exists because the tortured exists. Prison is an exercise of power: from lawyers to the State, the police.

There is a system in society that conditions the existence of the oppressed and oppressors. It seems the only thing we find as a society. It is also the cruelty of the human being. In Chaco , to review this is to find a way of thinking, a mechanism to give images to a war that has no images. The biggest thing you have are black and white photographs, very few moving images. The photographs are taken by white mestizo soldiers or by white adventurers.

The context of the time makes these people have photographed from top to bottom. They show Quechua or Aymara as a phenomenon, as something phenomenal. There is a lot of class manifestation, racism and ignorance: the destiny of those Indians was to go to their deaths. The destiny of that target was to have the possibility of being saved. Those Indians did not have names and the whites and mestizos has statues, squares. The indians don’t.

In the construction of images is that there is not a vast literature in the analysis of what happened. There is no such thing, for example, as there is of the Second War. From that, a literature has been developed that goes beyond telling what it was like but rather analyzing those who did all this, those who suffered, those who allowed those who were silent.

You said that Chaco was born from the silence of your grandfather, what was that silence like?

It took over my grandfather when he spoke or tried to tell us about the war. That silence as a manifestation of pain and trauma apparently happened in the Chaco, when he was 17 years old.

Part of the film is the sonic sensation of silence. When I was very young we went to visit my grandparents, the big meal. At one point, it was divided: the men went to one side, the women to the other. I was a child and could circulate in both spaces. My maternal grandfather went to war, when he met with his brother and his sons-in-law the question of war always arose. Then they began to tell about the war, in a humorous way at first: “we bathed in kerosene”, “we slept under the cars, which was the coolest place”, “we bathed in mud”, “we had to drink urine because there was no water”. Then a deep silence began, because those bodies began to remember all that. There the silence began, the silent crying: of my grandfather and his brother, they really began to remember.

My grandfather was taken prisoner and was imprisoned in Paraguay, he was a tango player, he had some talk, he had gone to primary and secondary school, he had advantages. He was the servant of a Paraguayan general or officer. He began to have better treatment because he taught the daughters of this officer and the family to dance tango for the fifteen years of the girl. He was laughing a lot, showing the gunshot wound.

My brother told me, after the movie, “your question did make sense”. All Bolivian youth of that time are dead people, people who have returned with very strong traumas, they have returned mutilated, of spirit, of soul, they have faced death in a very cruel way. Those people have built Bolivia.

Official narratives say that, from there, they hoisted what is now Bolivia. Well, yes: they are mutilated people, people with a lot of trauma, who built dysfunctional families. Those who suffered were his companions and their children. This is a society that is being forged from a war.

It happens to this day, when they go to do military service and the military makes a mockery of Quechua, the one who cannot speak Spanish well. So what he does is nullify a culture, a person from his language. They begin to learn that military jargon, a very macho, misogynistic, violent attitude. That is the problem of not understanding a country.

There is a debate about the point of view. The evocation of my grandfather what proposes is a story and a fiction. Imaginaries are proposed. The official narrative is the patriotic sense, the construction of heroes and I am against it because I need another point of view. I ask questions because I do not believe that what I have been told is true. Much of our work is to distrust images, “I need the other part.” You need to be suspicious.