Pablo Allison was studying a photography diploma in England when arose the possibility of taking photos at jail. Together with some colleagues, he headed for the prison. He took pictures trying not to miss that chance that he, he speculated, would hardly be repeated. What he could not foresee is that a few years later he would spend several months in that same prison for a conviction for his other passion: doing graffiti. It was a key experience in his life and his work, the product of which not only would come a book but also a way of seeing the world.

The graffiti and his passing through jail transformed him. “They have helped me a lot to be able to break boundaries and get into places that maybe as a photographer I couldn’t enter,” he says. Both experiences are “a passport” for him to enter other realities. To that is added the duality that runs through him: son of a Mexican mother and an English father, he grew up between both cultures. “Let’s say I split myself in two,” he acknowledges. This tension was one of impulses that led him to search for the stories behind those migrants who travel north aboard “The Beast”, that train that roars, kills and transports people to the border with the U.S.

Pablo does not define himself as a graffiti artist, he is uncomfortable calling himself an artist and he does not perceive himself as a photographer. It’s all of that, yeah. But that sum gives something else, a different result, the one that cannot find the right contours. So if you ask him, he will only say to call him Pablo, he is fine with that.

Do you feel that your work has changed over time?

It’s quite a challenging question. Let’s say I split in two. My life has always been split in two: half English, half Mexican. So, from there, it is a bit difficult for me to understand the world.

I paint in the streets, I have been doing it for 25 years. And, at the same time, photography. But I never wanted to mix one with the other for various reasons. Now the world has opened up more and understands that graffiti is an artistic expression and generates money. But hey, there is a very big conflict for me and for many people who have been doing it since when there was no market for it.

At present, I work on the migration issue and I have mixed what I paint and the photographic documentation that I do. I muttered things. Not so much because of me, but because people responded in a rather unique way. Most of my work is focused on an audience that is not totally related to photography. I think it is easy to communicate a social issue to someone who is interested in photography and human rights issues. I am not opposed to that, but it is easier for me to reach an external audience that likes graffiti as such.

I think I understood that the words I paint and what I illustrate with colors resonates with people and that is where I also put my documentary work on migration. People have responded very well.

Sadly with my work I can access economic means, in Europe and the United States, but not in Mexico. It then reaches an audience that does not know very well about the issue of Latin American migration, which is perhaps very similar to what happens in Europe, but I think that always seeing the external we value it more

And how does it impact the fact that you were born in the UK and moved to Mexico as a child?

I was born in England and at the age of three and a half we traveled to Mexico. My dad is English and my mom is Mexican. We migrated because the situation in the UK in the eighties was not very favorable for my parents.

There was the (Margaret) Tatcher government and it greatly reduced opportunities. At the same time, my mother wanted to return because she no longer wanted to live in England, she had already lived there for about fifteen years. And well, we came back and I really liked it. Now, looking at things, making a general panorama, an analysis, it enriched me a lot to be able to be linked with Mexican culture, because I believe that English culture is very dominant.

Did you feel like a migrant? Did that have anything to do with your getting to work on this issue?

I came to Mexico when I was three and a half years old. When we arrived we had to enter British schools because we did not speak Spanish. We went to elite schools, those who attended were foreigners or came from wealthy families. My sister and I did not have the means that most of the kids who went to schools had. I remember a lot that I felt discrimination from kids with a lot of money. At one point, we even went to a party in an area of Mexico City with a lot of money and they asked us where we were from, because obviously we stood out. And I replied: “From England.” They made fun of us saying that we came “from the bitch.” It is interesting how that feeling of class or discrimination existed.

Three years later or so, my parents made the decision to remove us from those schools. By then we had already adapted to Mexico. They put us in public schools and from then on I never received those treatments that we receive in schools for “nice” children, as they say in Mexico. So, I always felt Mexican, even though I didn’t look like one physically. But when I open my mouth, I already reveal the Mexican.

You were jailed for doing graffiti, how was it?

Yes. It was in England. Since 2003, the UK Police have been investigating a group of people who painted graffiti. And in 2009 they started doing the formal investigation. We were arrested between 2009 and 2010, all the people who they believed were involved with this group. And in 2012, me and three other people received, as they say in Mexico, “autos” from formal prison. The sentences were different. I received the minor: 19 months in jail.

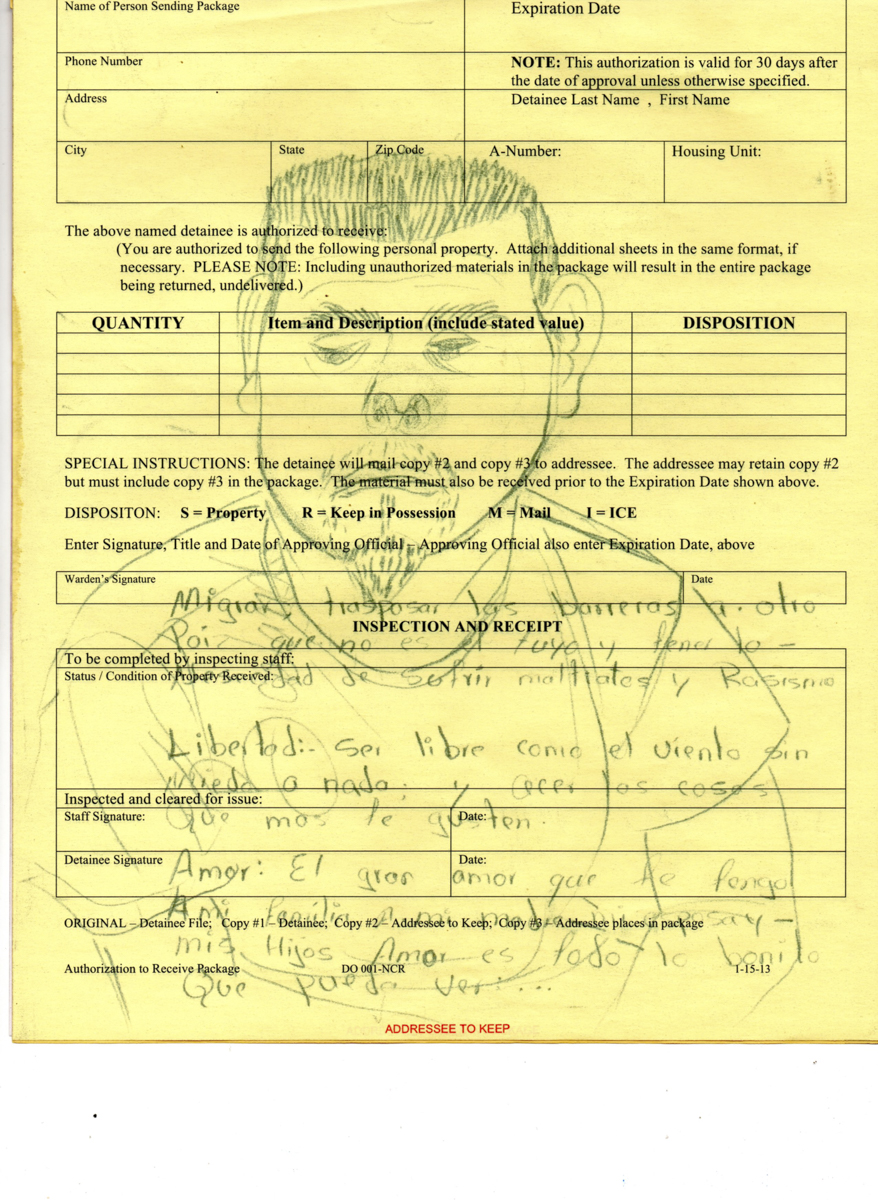

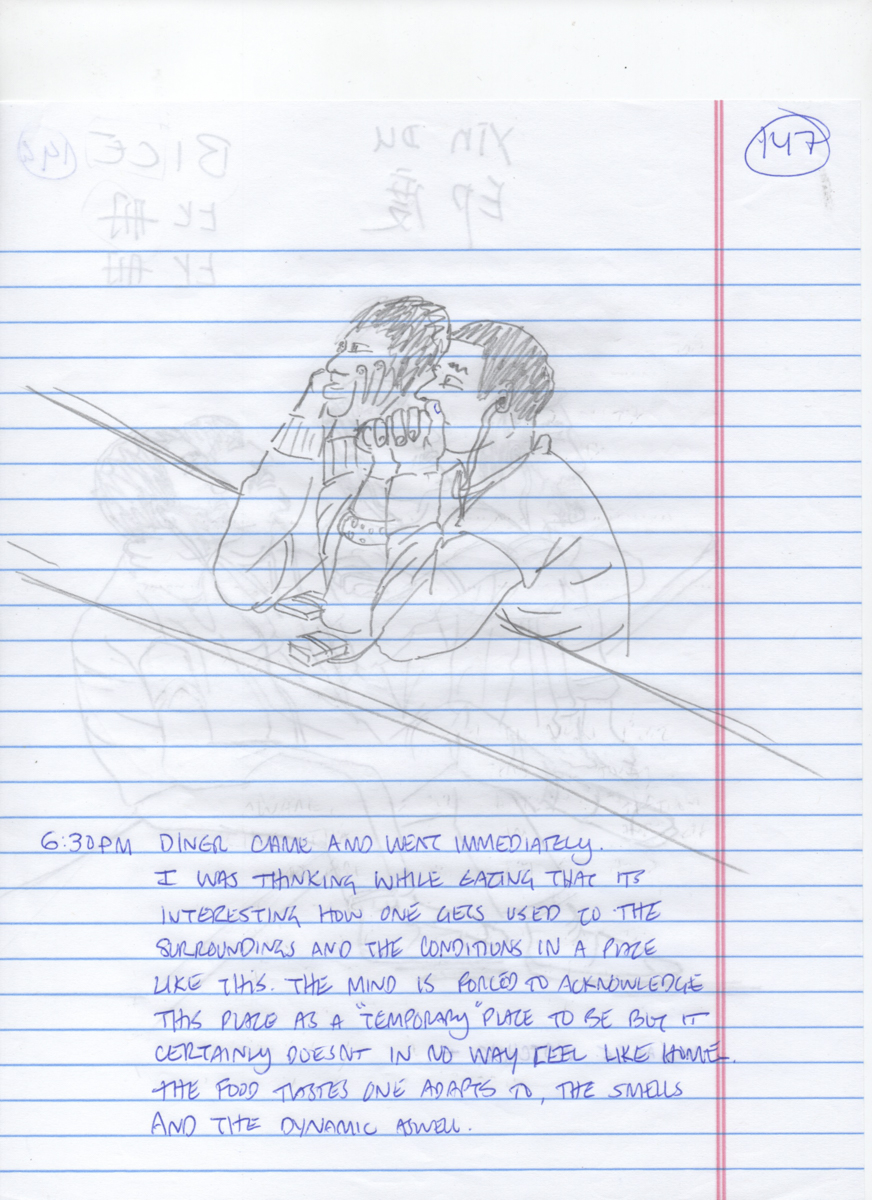

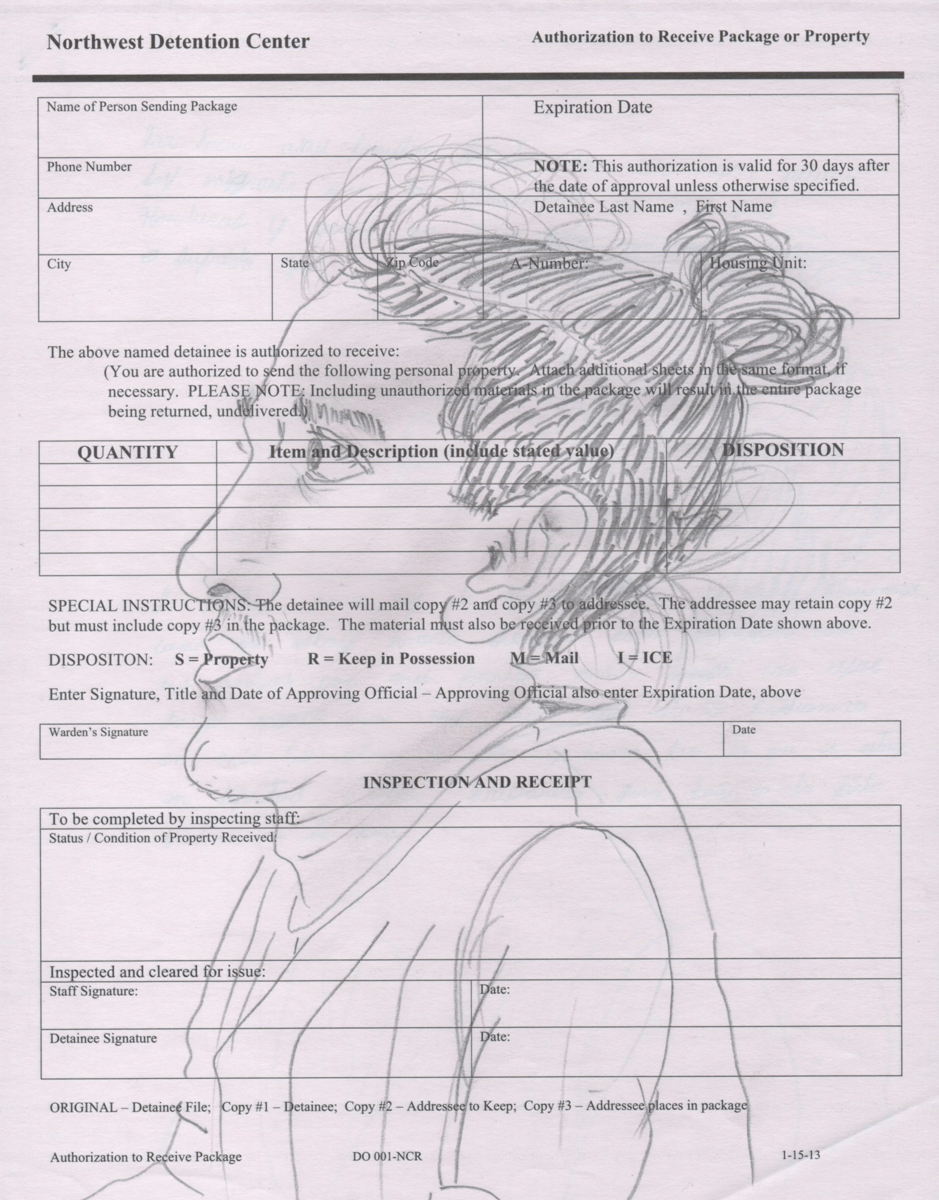

From there came a book that you made with your sister…

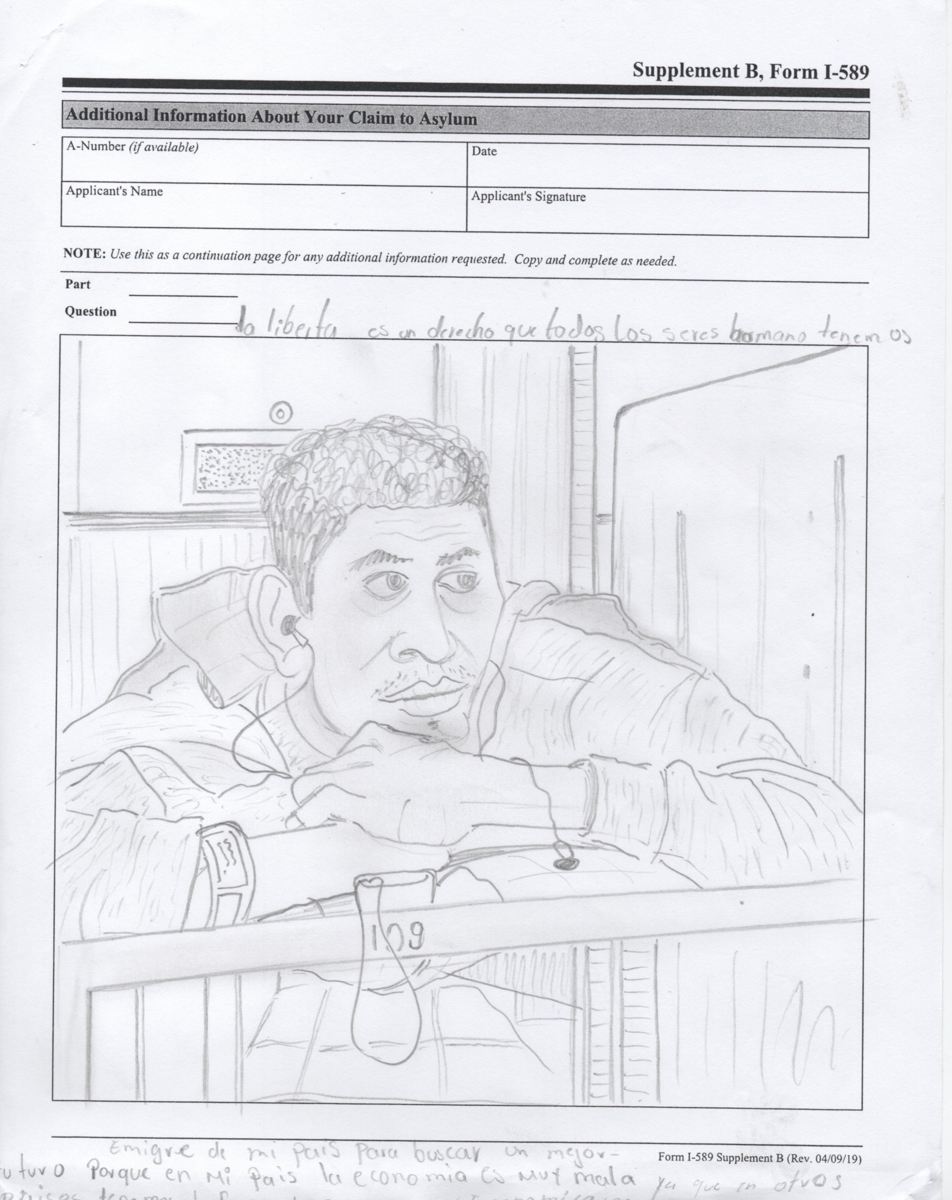

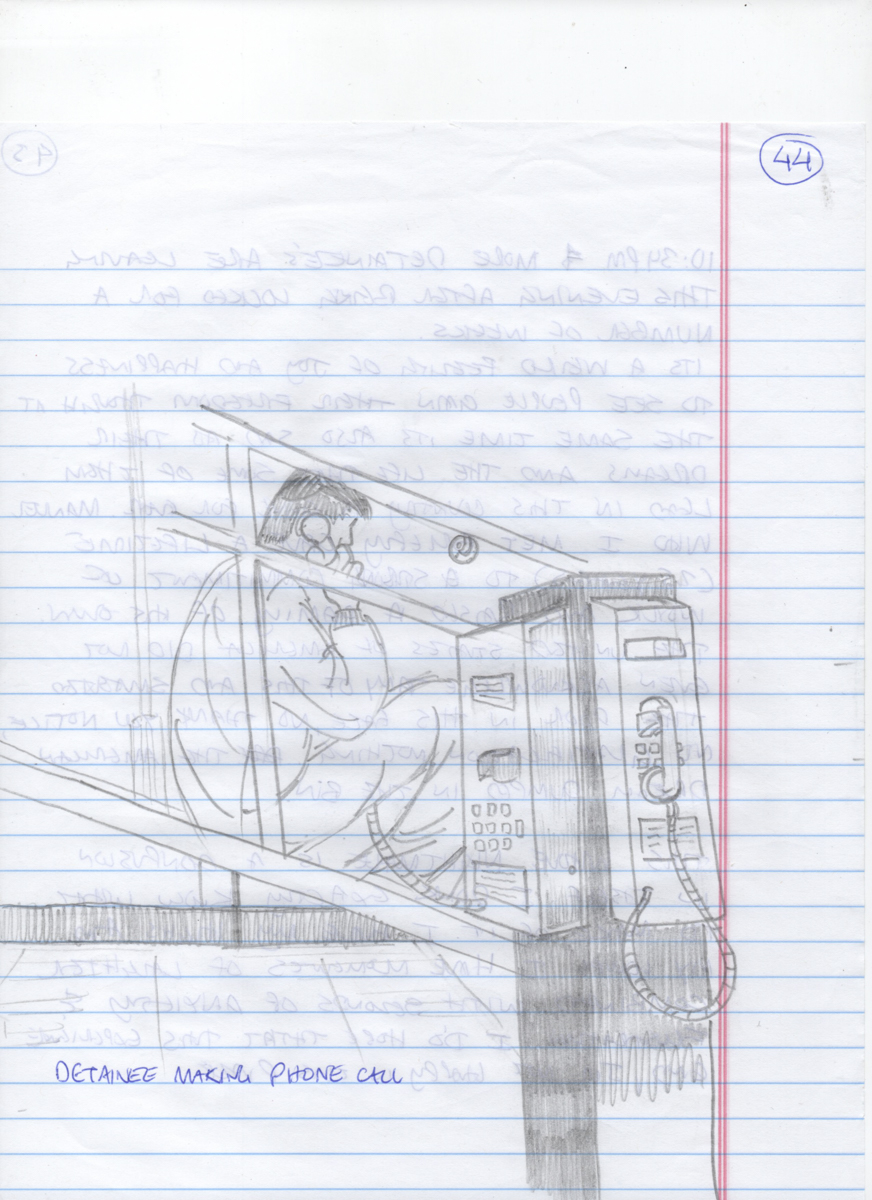

Yes, it is actually a joint work, my sister and me are authors, we collect documentation of the prison, drawings and photographs of feelings related to confinement and freedom. And it took us a long time because it was a project that we started before they locked me up, from the moment the police go to my house and ransack the house to find evidence. From that day until the moment my sentence ends. I did not serve the 19 months in jail, but I spent a third of the sentence in jail and then the other two-thirds in confinement conditions, but at home. It took about seven years of work and then we made the book called Operation Jurassic, which is the name of the operation carried out by the police in conjunction with the UK Traffic Police.

It was published in 2018 and, luckily and surprisingly, it was a success. One hundred copies were printed and sold out in two weeks or so. That encouraged us a lot because you never know. When you post something you say “well, I’m going to invest it and see what happens.” The public that consumed this work was a public that was related to graffiti, so that also benefited us a lot. With my sister we also always wanted to focus on the photographic public but in my case, for example, people know my work through graffiti.

And how did that time in jail impact you?

In 2005 I was studying a diploma in photography in England. And they invited me and two other colleagues to go to a prison to document it. Is interesting because the issues of jail, criminality and all that caught my attention. Well, “I’m going to take advantage”, I thought. Besides, it is difficult to get into jail. I went to that jail, we did documentation, one day they showed us the most beautiful parts, obviously, and those images were going to be used for a contest, for a festival to try to keep young people away from crime and for them to see that the jail was not an environment in which to create medals. At the end I don’t know what happened to those photographs, but after a while I ended up in that jail: the same one that I documented due to fate. That was interesting.

In other words, I was already interested in the subject of jail, but it was as a result of purging that sentence that I became more interested. In prison my creativity exploded a lot because I was stopped in time. So there these ideas come up, like creating words, not just the typical graffiti that I love.

Afterwards you focused on the issue of migration….

When I got out of jail I started looking for work. I had the opportunity to work for Amnesty International in the UK and on the Central America team. I wanted to work with the Mexico team, but in the end I ended up with Central America and began to understand the context of the region a bit. I already had signs, but beyond gangs, I didn’t know what was going on. Specifically, four countries: Nicaragua, Honduras, El Salvador and Guatemala.

That was like a watershed in starting to understand human rights issues. After there I went to another NGO that worked more in the Middle East and Africa. Hence the idea came to return to Mexico because I was already quite tired of living such a routine life.

When I returned, it was clear to me that I wanted to make a trip from Guatemala to New York on the train. But I did not want to connect the trip with the direct immigration issue, I did not want to photograph people. My intention was to focus on the landscape and understand the landscape as if it were a metaphor to talk about the people traveling on that train.

In Mexico, before, there was a very great tradition of the train that transported people, but in the nineties the government privatized the lines, transferred them to concessions and now they are operated by three or four private companies. So people cannot travel by train. There are three or four tourist lines, but people don’t use the train to go from one city to another. I was very curious to know what existed on those roads where only migrants and goods pass. So that was the idea: get on the train and photograph the landscape.

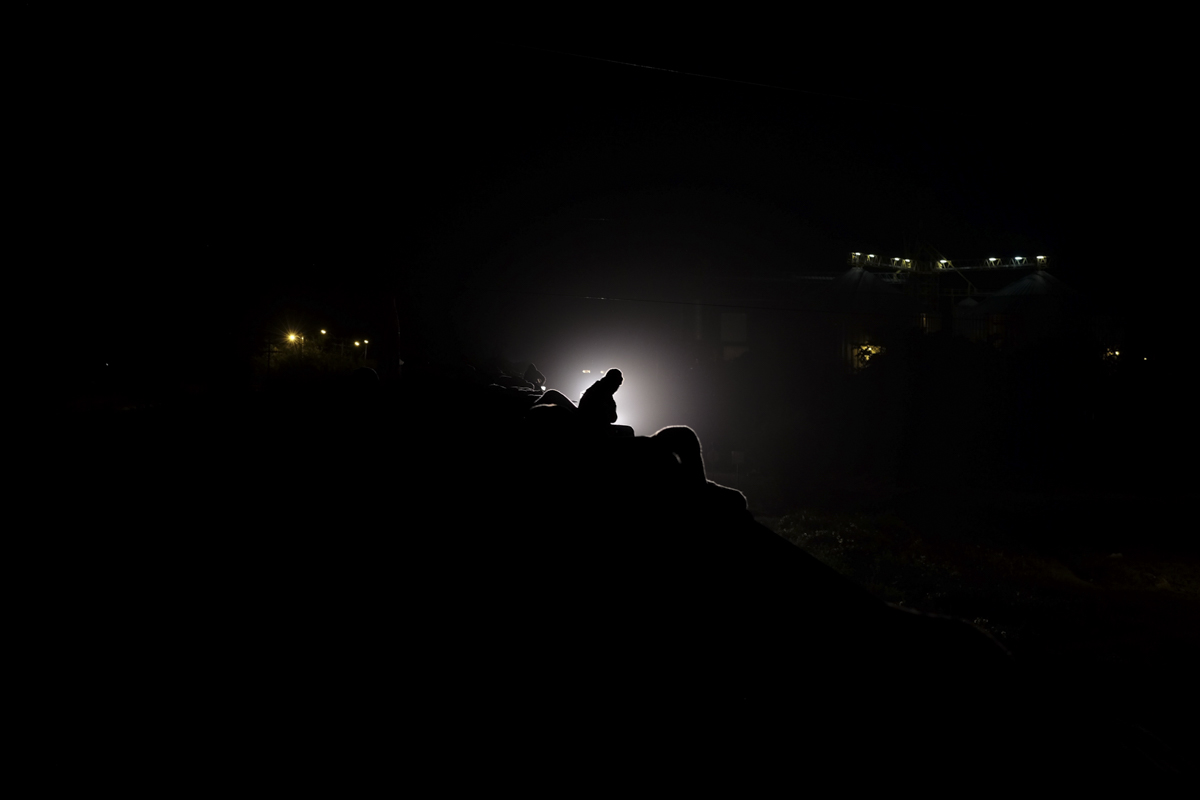

On the first trip I was able to tie it with the caravan that left in 2018 and from there I started two simultaneous jobs. There are two projects: one is called The Light of the Beast and the other is called The Landscape of the Beast. But the one that I give the most emphasis to is the first one because it is more direct and people connect more with that plot.

Why “The Beast”?

It is the name that the same migrants give to the train. There are many trains, but the train as such, “The Beast”, has all the characteristics to be called that. It roars when it goes out and when it goes on the road the horn that sounds a lot calls attention. And it also kills people in its path, because people sometimes do not know how to travel or are not careful and many times they fall and are run over by the train. Along the way there is organized crime that uses the roads to control the flow of people or, rather, seizes the roads to control the flow of people.

People are very religious, right? And use all these religious references to understand their situation, they entrust themselves to God, everything is under the word of God. So the name of the book has many references: not “beast” like the enemy, not like the bad guy in the movie. In fact, the name was born by seeing a situation and photographing it, creating an image where the train at night was coming out, approaching people and I was just observing the light. It was not difficult for me to give it that title and I feel very comfortable with it.

How was the process of getting involved with the people?

I have made several trips, not just one. In fact, I just returned from another not so long trip through the northern Sinaloa mountains. It has been for moments very intense and also very boring. Sometimes it takes me time to get involved with people. I don’t like being considered a press photographer because I don’t have that experience of photographing for newspapers. Very few times I have made that deal, I have been able to have commissions or sell images. I have observed in many caravans that there is a very great distance between certain journalists and the people. I’m not comfortable with that way of working. So, for me, it is important and essential to create a bond with the people I travel with and then have closeness and trust.

Many of the things that I have been able to portray, document, have been in a very natural way and also creating friends. To this day I communicate with the people with whom I shared experiences. Because finally I am an outsider. I don’t get on the train because I don’t have a choice. I get on the train of my own accord and what happens to me is the product of my decision. On the other hand, the people who get on the train or make that trip north, sadly, they have no other option.

So I remain as the person I am, as an intruder, but not an enemy, but an interested and curious intruder to know what is happening. And also curious to be able to help in some way. That is one thing I constantly ask myself: How much do I help?

I remember very well a situation where there was a lot of tension. I was on the train. We were going to the south of Veracruz, a very conflictive state in which organized crime has operated and has been a terror for migrants. We arrived at a terminal and a contingent of Mexican migration combined with heavily armed officers was waiting for us. We arrived at that train terminal like 600 people or so. They wanted us to get off the train. Before intervening, I spoke to a photographer and asked her if she could inform some media, because I have no contact with them and I knew that she worked with international and local media. And I said, “Hey, hey, can you make any mention of this? Because, if you don’t, nobody will find out and here they want to stop this caravan. And she said: “You don’t get involved in anything, take the best photos you can.” That disappointed me, she was not my friend but she worked on immigration.

I got involved: I stood up and stopped people throwing stones at officers who were ready to intervene violently. Fortunately no one reacted violently on top of the train, I got off and people believed that I was betraying them. We were finally able to mediate between the parties and they let us continue, but not on the train anymore. What they wanted to stop was the visibility of the caravan.

I have been directly involved and try to help people who need it and, at the same time, understand the situation that people live. Also the interest in graffiti has been another medium that has helped me a lot to be able to break borders and get into places. And the camera is a passport to different realities.