Rember Yahuarcani López is from the deep Amazon. The life of the Huitoto artist takes place between Lima, the Peruvian capital, and Pebas, a town of no more than twenty thousand inhabitants that can only be accessed by boat. Rember paints and writes: “What my work seeks, beyond hanging it in a gallery or museum, is horizontality, respect and recovering the dignity that has been taken from us in the last hundred years.”

According to him, throughout the 20th century, “academics, researchers, and social scientists linked to indigenous people had appropriated their voice.” For this reason, among other issues, he rejects the category of “indigenous art” because, for him, “art is art.”

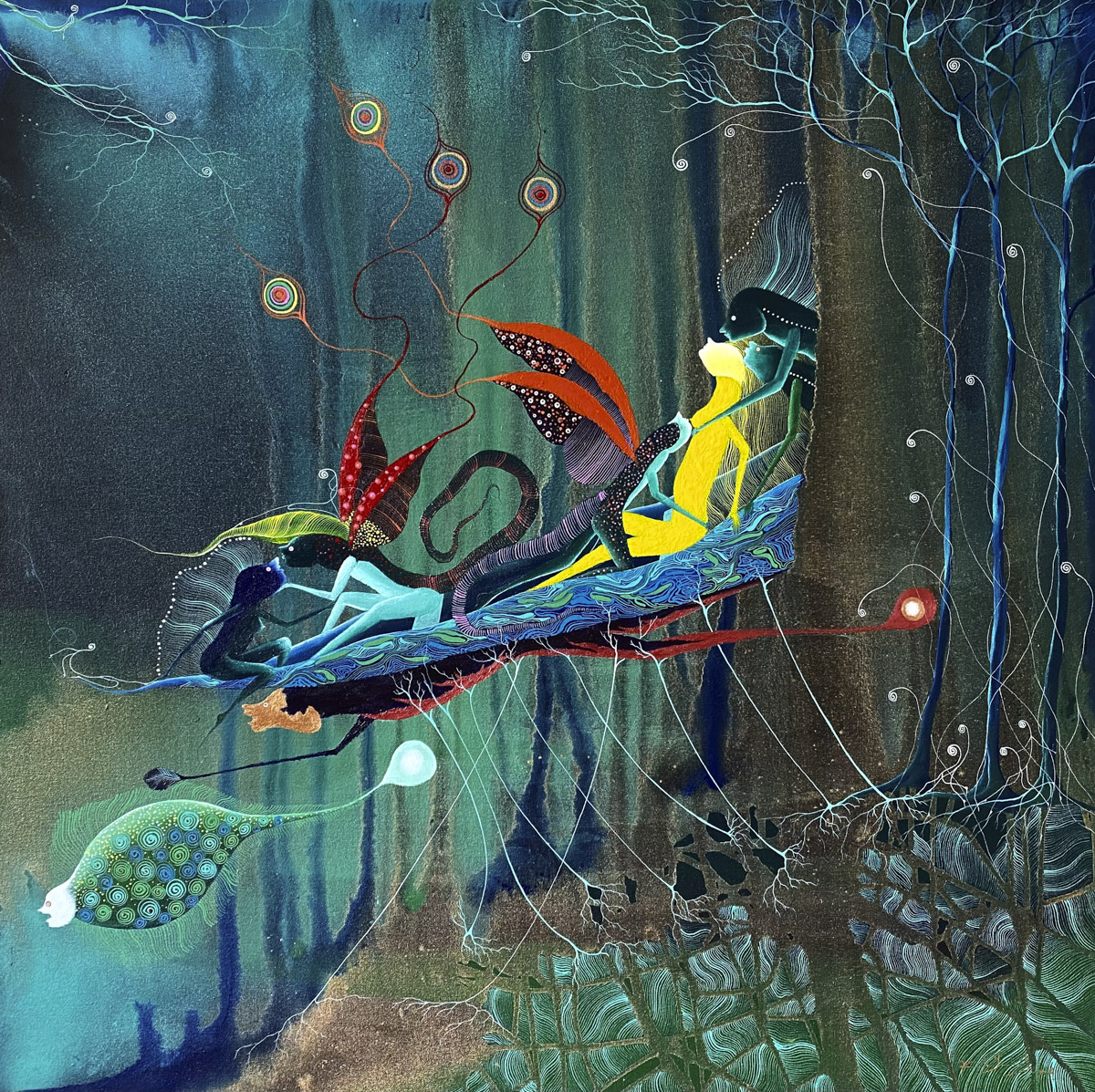

He seeks to reflect the worldview of his culture, the one he may have first heard from his grandmother but still learns: “Myths are in constant motion,” he says. Then, through the canvas, he tells the Huitoto conception about life, nature, death. His work has been exhibited in different countries in Latin America, Europe and Asia. Rember is currently working on a children’s “book-objects” that will be made from tree bark.

How was the transmission of knowledge from your grandmother?

My grandmother passed away five years ago. I learned the stories from my grandmother, she taught them to me. The transmission of stories, myths and anecdotes occur in different daily activities that take place in the community. There is not a single moment. They are transmitted when you go to the farm, when you cultivate cassava, when you go fishing, when meals are cooked. Myths are in constant motion.

I guess there isn’t just one version of things either, right?

We are related to the Boras, who are a very different nation: they have another language, other customs. But there are common features between these two peoples and there are many stories and many myths that are very similar. Now, within the Huitoto there are many clans. I am from the White Heron clan but there are other clans that also tell their stories and that is very different from my clan. But all versions are true. For example, each clan has its version about the creation of the world or the creation of things that exist.

And what is your clan’s world creation version? How do you think about death?

We are “the Creator.” We, the human being, the plants. It is a dream that the creator had to be able to leave a precedent. He created us and created all other things.

Our idea of death is very far from the Christian worldview one. For example, the concepts of god and devil for us are reversed: the devil lives above in the heavens and God is below. The death of a huitoto and where he goes after death is linked to the decisions he made in life. Huitoto is someone who manages to transmit the knowledge he received, either because he is a worker, because he did not steal or because he knew how to make coca and tobacco. All these values that guide the culture are going to decide where in heaven you are going to go.

Because after death you go to one of the seven levels of heaven, or space. And at each of these levels you also suffer and do not suffer; and they kill you. Either you continue doing the thing you did here or you live in a different way.

How did you get to painting?

My family has been dedicated to crafts since my grandparents’ time. We are five siblings and we grew up in a family dedicated to crafts. It is the form of family subsistence. We learned to weave, to carve, to paint, to make necklaces. Various activities, pottery too.

My father’s work became known little by little in Iquitos, which is the largest city in the Amazon and is on the way to Pebas, it is an obligatory stop. Once, my father had an invitation to a show in Lima and I took his place. I came from a town, I did not have study opportunities, I saw that painting could be a way to survive.

I read in an interview that your father said that a drawing is neither cute nor ugly, that the interesting thing is the story. Do you agree?

My father was always sure that the work he painted, regardless of the official arts, was important to him because of what it said more than because of the technique or the perspective or the characteristics imposed by liberal arts. So that was worth a lot to me, because it gave me the freedom to explore as I wanted on canvas or on the surface that I had to paint without ties.

Why did you switch from a more narrative perspective to something more pictorial?

It was because my work began to be classified in what many researchers and art historians consider “indigenous art.” Indigenous art is a category that I reject. Art is art. It is a piece of contemporary art, which seeks to be hung on a gallery wall in the same condition as the work of any other urban artist.

So, when I saw that my narrative, traditionalist work was being classified like that, I decided to move away and looked for a more personal language and a personal style so as not to fall into that category.

My criticism has always been that, throughout the 20th century, academics, researchers and social scientists linked to the indigenous people had appropriated their voice. Here are respected anthropologists and historians who have worked and continue to work. But, for example, about five years ago a renowned anthropologist became the author of a work whose content was the repetition of the testimony of many people about specific cultural traits such as food, hunting, healing. From my point of view that seemed very offensive.

If there is something that has fueled a lot that Peruvian society considers the indigenous world as a society that cannot manage its future, it is precisely that this academic world has not given the indigenous the tools to be able to develop and defend the world from which they come.

Those colonialist practices of the 20th century seem unacceptable in the 21st century. Furthermore, when we already have many professional indigenous people, many grandparents and grandmothers who speak in their ancestral language as well as in Spanish; and they can speak it very well. All this gives them the possibility to put their ideas in the first person.

And there are many, many academics right now who are reluctant to give up that practice that has been imposed for more than a hundred years.

In your case, you are giving voice to your own community…

Peru’s relationship as a state with indigenous society has been catastrophic. It has been an inhumane, uncivilized imposition. They have not given us the opportunity to say what is good for us and they consider us an inferior society.

Then, art becomes a tool, the articles that one can write are also tools. What my work seeks, beyond hanging my work in a gallery or museum, is horizontality, respect and recovering that dignity that has been taken from us in the last hundred years.

And from this debate, how do you connect with the academic world?

In recent years I have collaborated with some anthropologists. For example, write an article on a particular topic. I believe that the collaborations will help to relate this situation of inequality between an academic with his university knowledge that is respected and a grandfather with his ancestral knowledge.

So, to balance in some way, I think that what academics have to do is look for formulas to be able to tell the person that the knowledge of grandparents is just as important as the knowledge that a university has. This is where this collaborative work with anthropologists, artists and people linked to the academy goes.

Another example: there are no indigenous artists participating in contemporary art fairs, in contemporary art biennials, in contemporary art museums. Art made by indigenous people will continue to be considered second-rate art. There is the challenge. It is a challenge not only for art, but also for curators, museum directors, gallery directors to achieve an opening to a work that I consider to be avant-garde.

“There are no indigenous artists participating in contemporary art fairs, in contemporary art biennials, in contemporary art museums.”