The father of Ramón Campos Iriarte gave him a Hasselblad 500 camera. In addition, he usually carries a Leica M6 on him. Working with analog cameras, indulging in the leisurely time of film photography generates a particular adrenaline rush: knowing that you have a certain number of photos to shoot. That forces you to stop and watch.

He follows a similar logic in his way of directing the Gabo Foundation’s “Fund for Research and New Narratives on Drugs,” a program to promote innovative journalistic work on drug policy in Latin America. Ramón is convinced that “to change the narratives is to change the focus of the stories.” Just like when you have a single roll of photos: brake, think deeply, focus.

He studied political science at the public university and has always worked on social, political and environmental conflicts. From his role, he reflects on the change in the rules of the journalism game based on the new financing mechanisms and on the decline of traditional media. And he concludes: “You have to be optimistic.”

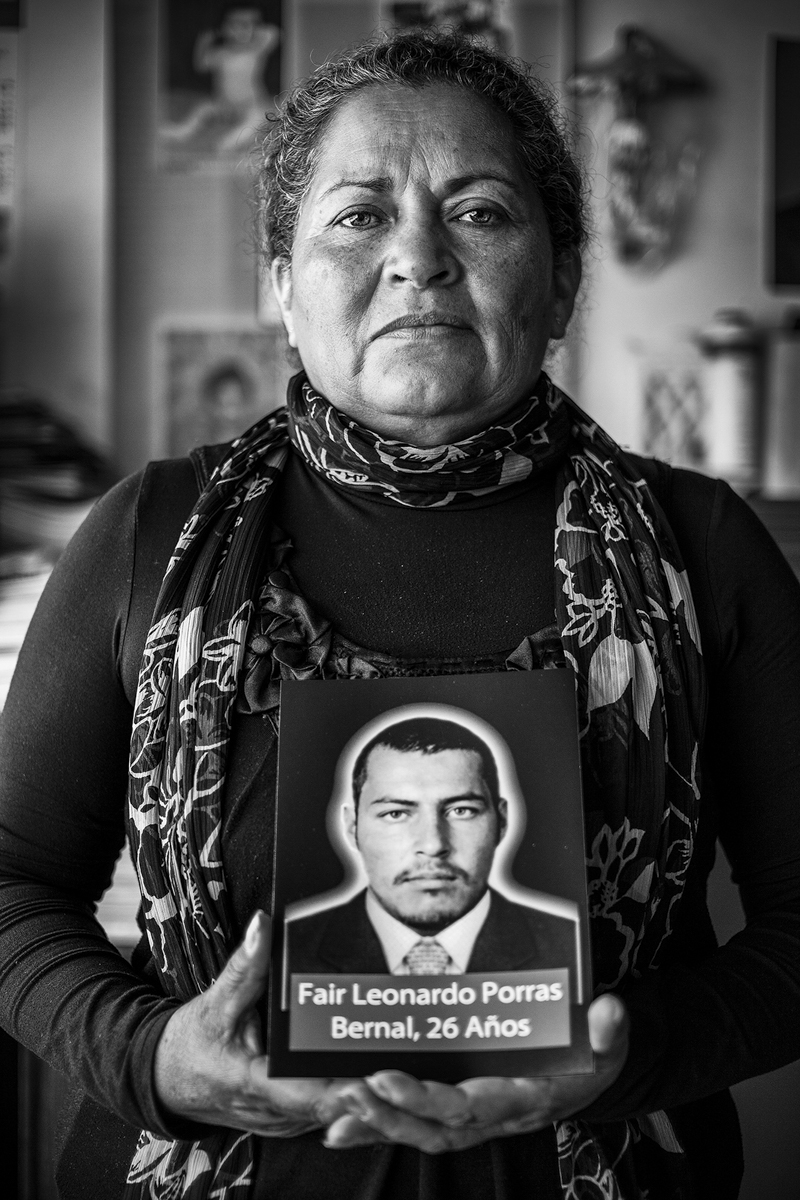

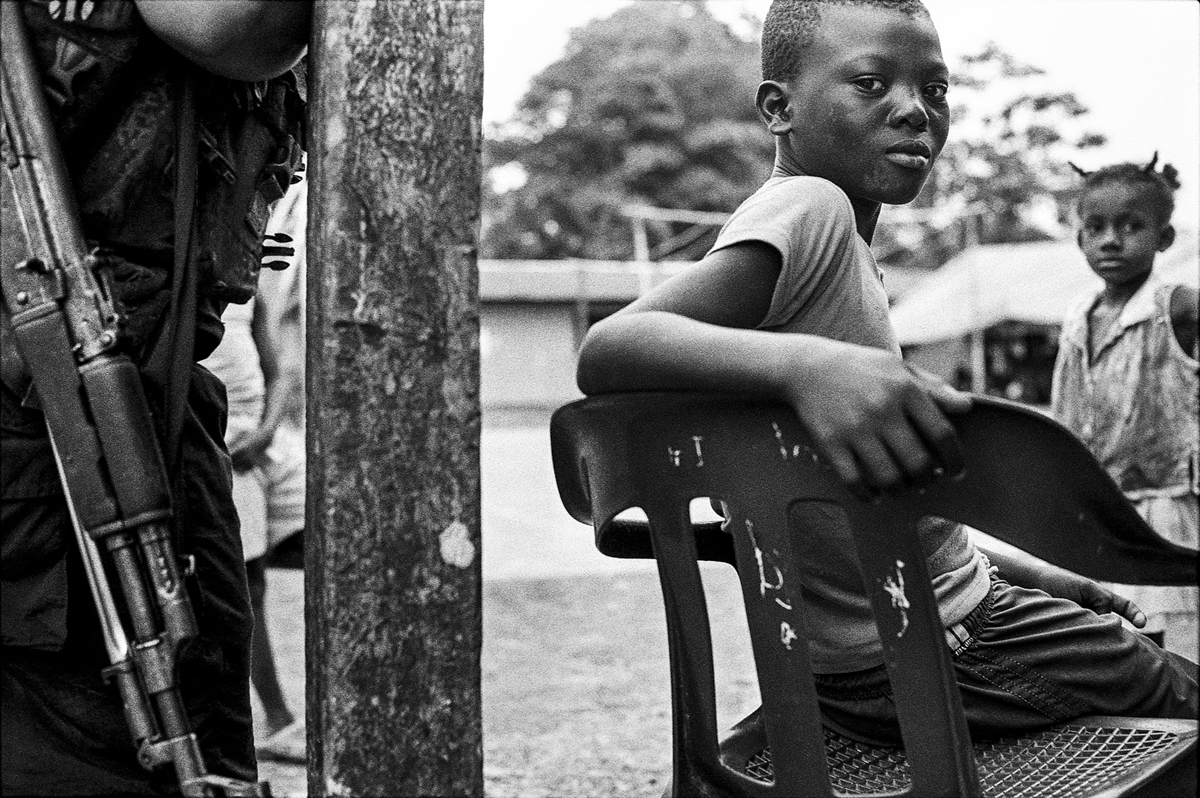

“The reason why these drug policies must be changed is because they destroy lives,” he says. Ramón identifies that a community is being built among those who study, research and record stories around this issue. A community that does not escape complexity, that knows that it is not only about “good” and “bad”. A community that understands that telling particular stories in depth and in a humane way allows a better understanding of the setting and its chiaroscuro. “When you are in the countryside and you have no other option than to plant coca to put your children in school, that makes you, I don’t know if a victim, but certainly not a drug trafficker,” he says.

Since when have you been a photographer?

Lifelong. My grandfather gave me my first camera. I learned from my dad, my grandfather, my dad’s friends: I’ve always been surrounded by photography and photographers. I will have started posting photos, maybe fifteen years ago. Photography is very difficult to make a living. I don’t know how those who are full-time photographers do it. Personally, I have had to write a chronicle and make documentaries. That is my balance. Plus the subject of the activity a little more academic, the funds and such. But let’s say that my passion has always been photography and analog photography because almost everything I do is analog.

My father is also an anthropologist and documentary maker and worked for many years with British TV, making documentaries about the armed conflict in Latin America. He was with the Sendero Luminoso, he was in Central America during the wars, he was in Colombia; I have rarely worked with him but he was always very close. He is also a photographer, so lately I have rescued his files and slides. There are treasures that I had not discovered until now.

Not only are you a photographer, but you also have a broad overview of how drugs are treated in the region. How do you see that scenario?

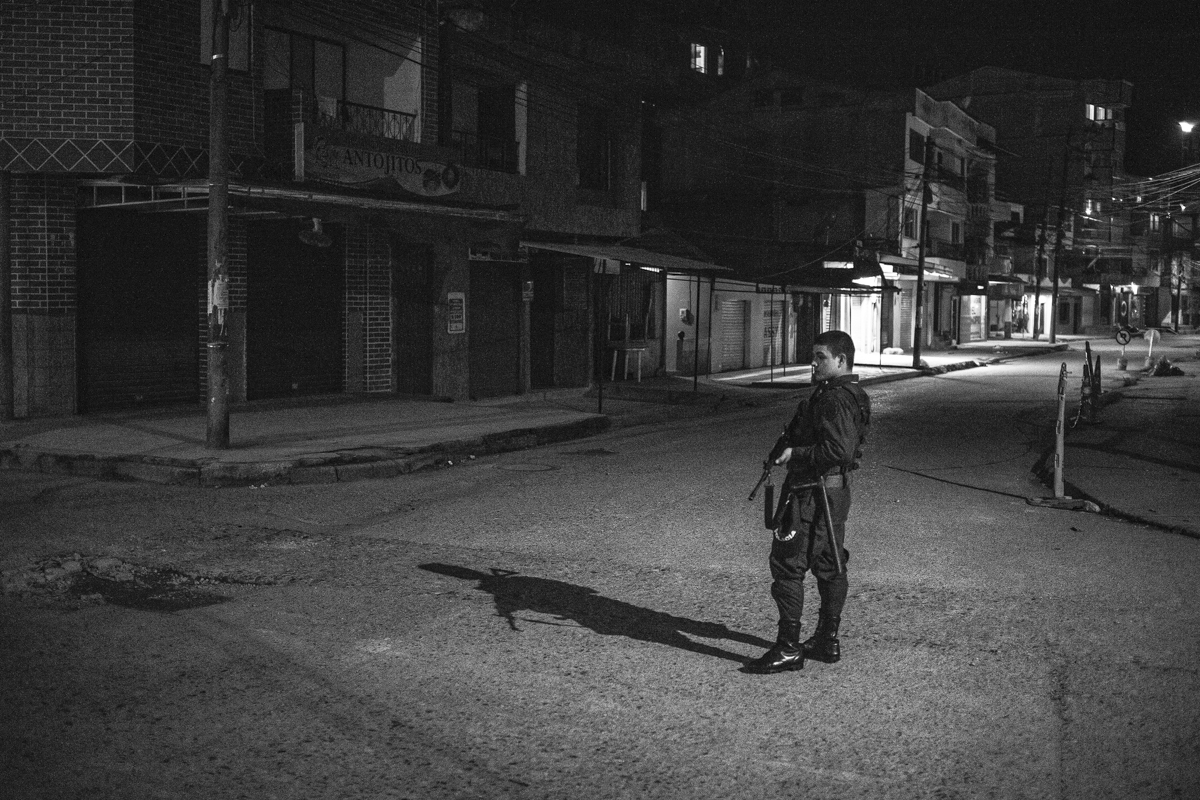

I think that, as a Colombian, one is very close to that issue for having been born and raised here. Just doing a little journalistic work is enough to realize the resounding failure of drug policy in these countries and how it has wreaked almost indelible havoc in this society, the environment and communities. And to see that this cycle continues to repeat itself infinitely because we are still attached to the policies that the United States dictates to ban drugs, which is almost implausible.

In the face of any action, let’s say that there is resistance, then there are many people in Latin America who are organizing themselves, who agree to reject this drug policy that has already been proven to fail.

We make the effort, from the academic and journalistic side, to give space to people who understand that drug policies are a failure; for journalists to meet with academics who have already investigated the subject. All this is based on factual evidence that shows that failure. None of this is speculation or ideology, but numbers.

The work of journalists in our Fund is to interpret that evidence and give it the form of storytelling to try to appeal to the consciences of the people through the media.

Would you agree that new languages are emerging and that images that had us a bit saturated are being renewed?

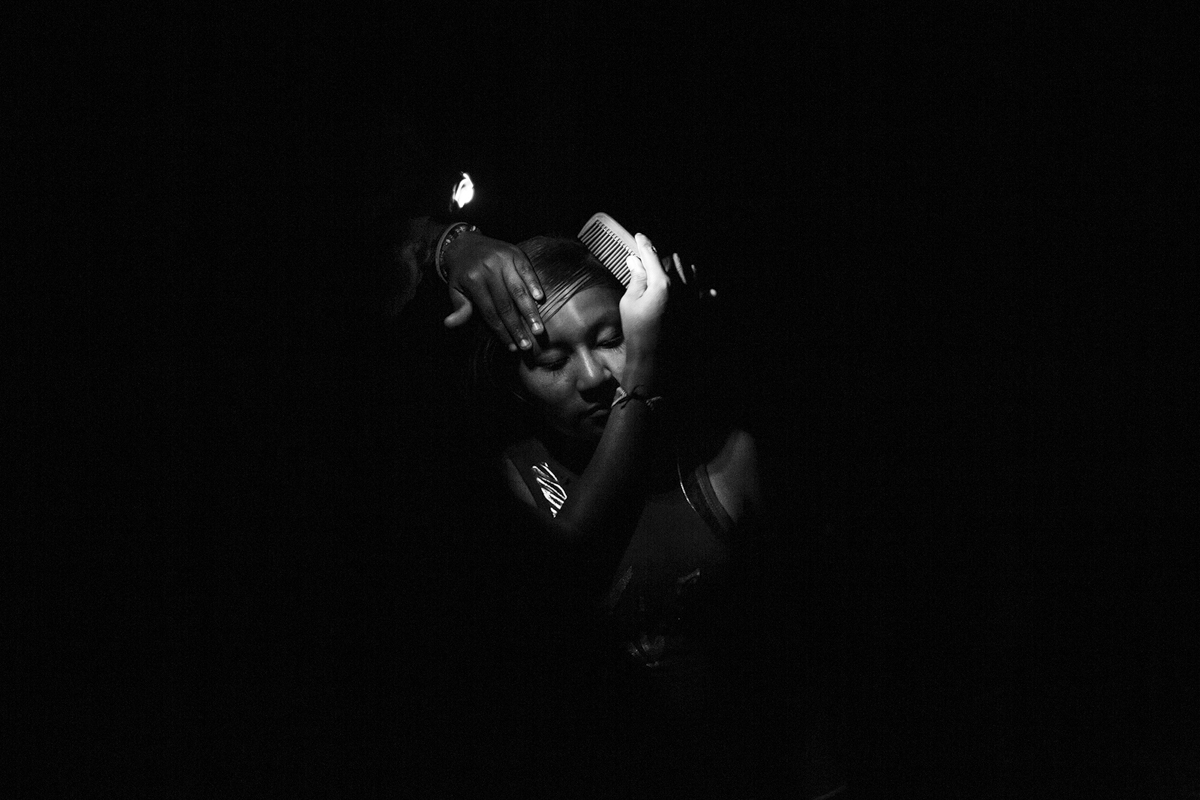

It is part of the base of looking for new narratives. The Fund is in the name of that, of renewing those narratives because people are saturated with seeing the same thing and we believe that part of the problem is the traditional narrative around drug policy. These novel approaches, perhaps from the aesthetic point of view, help a little to reach another audience, to convince more consciences of the things that are evident.

In any case, it is important not to neglect the scientific side, the factual side of the drug policy issue and that the journalistic issue does not become art, because there is a fine line between art that protests and that innovative journalism that has non-traditional visual narratives. At the Fund, we demand that journalists add a vein of tough, investigative journalism to accompany these visual narratives.

There is also a shift in focus, there are more and more autobiographical works…

Of course. Let’s say that the basis of changing the narratives is to change the focus of the stories. Now the search is more about personal stories, stories that show the complexity of the issue: how drug policy affects human, individual and community level; how the failure of drug policy causes harm in those communities.

It is about showing that it is a much more complex issue than simply pointing out a community of drug traffickers, which is what has happened. Today we try to look a little more at a micro level: personal, family, what happens when you are in the field and you have no other option but to plant coca to put your children in school and that makes you, I don’t know if a victim, but certainly not a drug dealer.

And along these lines, would you recommend some authors or works in Latin America in particular?

We have tried to link to the Fund people who are very aware of these issues, both from an academic and journalistic point of view. There is one person who seems to me to be key in understanding drug policy in Latin America, especially in the countries of the Southern Cone, and that is Guillermo Garat. He is one of the mentors of our Fund and he is a journalist, he writes and is very clear in terms of what is wrong and what is not in drug policies and journalistic narratives that tend to better explain this phenomenon.

There are also study centers that produce very good reports, such as the Universidad de Los Andes, the Center for Security and Drug Studies, from here in Bogotá and there is María Alejandra Vélez, who is the director and is a well-known researcher . They produce reports that are academic but have somewhat digestible language that is not traditional brick. Our idea is to bring together these types of research centers with journalists so that they can produce things in a language a little more popular in the media. There is also Dromómanos de México, who do a very cool job.

There are many people working on these issues: Jorge Panchoaga or Luis Ángel, in Colombia, Carlos Villalón, with the issue of coca in the Americas, Céesar Rodríguez and Emmanuel Guillén, in Mexico, they have an excellent job too. This issue is huge and touches all the countries of the region. A community is being built.

Our hope is that the Fund is not something like giving a money, doing a project once and then disengaging. Our hope is that these people are interested in the subject and continue working. That is no guarantee and there will be people who do and others who do not.

The issue of drug trafficking and the war on drugs has produced journalism for many years, we are not inventing it, far from it. We are simply trying to put a more human spin on these stories.

Drug trafficking journalism in Colombia, Mexico or Peru has always been extremely biased and closed to an official narrative, and that is what we are trying to change. I think there are people who understand it; even in the media, publishers are beginning to see that reproducing police or military communiqués is not very sustainable today.

How do these new modes of financing impact the practice of journalism?

Everyone is suffering economically and the traditional channels (the media) are losing the possibility of financing field projects. That is why funds such as ours or Pulitzer or Nat Geo scholarships gain a lot of space among the journalistic and independent community.

Today there is excellent quality content on the internet from very good independent projects that do not necessarily have to go through the CNN page, or whatever medium. The Internet makes that easy. Even Instagram, or social media. There are excellent projects that only go digital and do not enter that mainstream of the media. But for young people, those platforms are the ones that become more relevant.

Here in Colombia, and in many places, is the figure of the “parachute journalist”, which is unfortunate. We have also given war to that because there are still many media outlets sending guys to cover “wars”, taking out sensational things and such. That fanciful story still exists but I think it is increasingly marginal, thank goodness. The media is adding a bit of quality to the coverage now. Our margins tend to be strict in the monitoring of projects, we do a precise monitoring for each project. I think that is another advantage of the Funds.

People often talk about the media crisis and how the networks end up restricting speeches, but you are so optimistic …

I think you have to be optimistic. As a Colombian, if we were not optimistic, we would all commit suicide because there have already been many years of defeats. The issue of networks and the internet has brought a lot of frivolity to journalistic coverage, on the one hand. But, on the other hand, you also see young people, who are just starting out, who receive money from somewhere and take out a pod that is a bomb in terms of quality. That gives hope.

In Colombia and the United States, which are the two countries in which I know the industry best, there has been a total dismantling of the mass media. To a certain extent, in Colombia the mass media are ending because they have lost credibility, because they are not financially sustainable and every day it is like that alternative media of young people, self-sustaining, financed with something, are emerging and are the ones that are actually banking the stop, in journalistic terms, at least in this country.

The golden age of media is over. These small media can emerge and end in relatively short time, but they are the ones that are bringing corruption investigations, questions, complaints of human rights violations, interviews: everything is done by people from independent media.

I understand that you have contact with everything new and with tradition as well, in addition to living it in the first person. Do you feel that these two aspects fed your gaze?

Yeah sure. I really like the black and white photo, analogous, a very little experimental look. I don’t know if that’s good or bad, but my work, at least in photography, is very traditional. Today there are photographers who do much more experimental things and who are at the forefront of that photography. I am much more traditional in that sense and that responds to having been in contact with that photograph from before, of Don McCullin, of James Natchwey, of the legendary black and white reporters who covered conflicts. Why would that aesthetic necessarily have to end, right? It is good that there is parallel innovation but I also think it is good that some of us continue with that traditional eye. Almost everything I do is 35 and 120. It’s what I like to do the most.

My first 120 camera I inherited from my dad, it was a Hasselblad 500c, like a 55 or something like that and it is a beauty of a camera, I still have it and it works perfect and the photos it takes, its quality, is incredible. I really like the aesthetics that these cameras produce and I always also carry a Leica M6 which is the old and reliable 35mm. They are very tiny, today’s ones weigh twice as much.

That way of having a camera in hand and knowing that you have 12 photos and that you have to take advantage of them. When you are with young digital photographers and you hear the shutters from the cameras, you think: those people are going to come home with 12 thousand photos today and I am going to have 8 or 9. That forces you to stop. Sometimes when I take out the digital one, I come back and see that I took 25 photos and no more. I get used to walking with the analog and not shooting at everything that moves.