After taking photos at the wake of colleagues and friends, Mexican photojournalist Félix Marquez felt that this could not be the end. He knew that –at least– one chapter of the duel was missing. One day, the son of Moisés Sánchez, a journalist murdered in Veracruz, told him that he still had the loudspeaker that his father used to tell news about his town. Felix came up with an idea: he would photograph journalists who were victims of the so-called “war on drugs” through the objects they left behind, such as a rosary, a credential or an old camera. Thus was born Vestigios.

In the middle, Felix had to leave Veracruz. “Here it is always said that you can be the next murdered,” he says. He spent time in Chile, where he was able to work on other types of stories and, as he says, “shake off that objectivity or neutrality that they teach in journalism schools.” Later, when the former governor of Veracruz Javier Duarte was arrested, he was able to return to his homeland.

In his memory there is an idea that comes to him all the time: he never thought he would end up doing what he does. It was not his plan. As a young man he liked photography, he took pictures of concerts and recitals. But the violence prevailed. According to Reporters Without Borders, in 2020 Mexico once again ranked as the most dangerous country in the world for the practice of journalism.

How did you start photographing violence?

Through personal experience. I was at the University studying journalism, around 2009, when we began to register a very high rate of violence in the state of Veracruz and in Mexico, within the framework of what was called “the war against drug trafficking”, launched by Felipe Calderón.

We came from covering other types of stories, some colleagues came from covering social things, especially inequality. I was very young and what I did was photograph concerts, as a hobby. I liked the photo, I covered concerts. By 2009 war broke out in our faces. The violence arrived at the school door, with bomb threats or armed confrontations, executions in front of my house. I couldn’t turn to the other side because the situation was in front of me.

That is why I say that we become war photographers without wanting to. I never imagined that, starting my career, I would have to cover that violence and see this cruelty, so real. It was something that impressed me and continues to impress me. The cruelty of the events has shocked me greatly. Mexico is compared with countries that are in armed conflict.

How do you find another point of view from which to tell the violence?

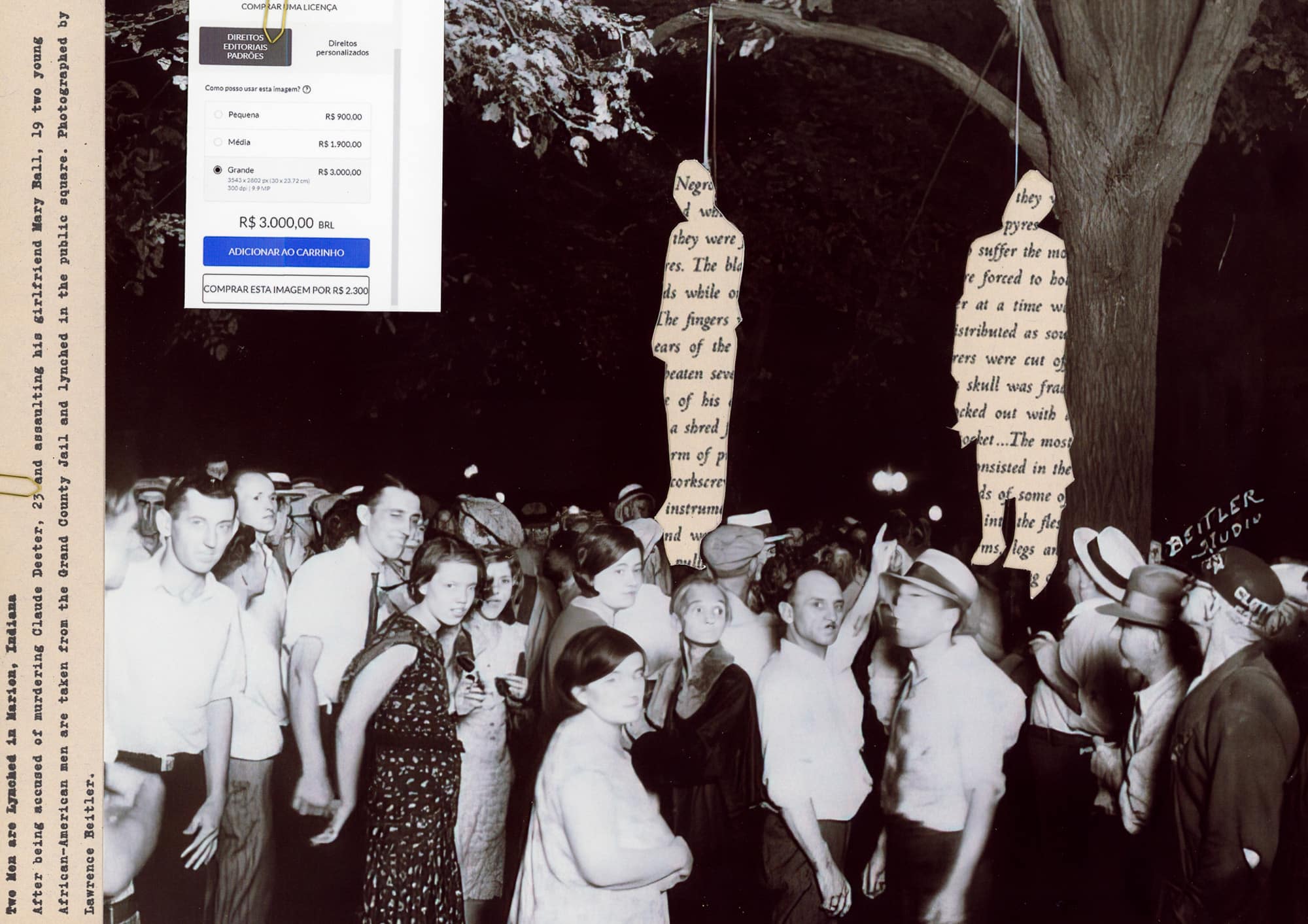

It was very complicated, we live in a country where the newspaper that brings the most deaths is the one that sells the most. The photos I saw as a child were very bloody images, very bloody. I had to reinvent myself to be a little more subtle with the images I made: I tried to carry a tripod to be able to take another image or focus on details.

I was trying to counteract a little the photography of the newspapers in Mexico, the nota roja newspapers, yellow journalism. But it was difficult. At first I did those things too. When I left I thought about what I was doing and when I got home sometimes I couldn’t edit the photos because seeing them was a very strong shock. I started working from another side, putting myself in other people’s shoes, thinking that I would not like to see a relative that way. It took me a long time to understand and train myself in that thought.

Do you remember the first coverage you did on this topic?

I remember the one I didn’t do. In Veracruz, two drug cartels were fighting for the place. One day there was a horrible scene: 35 bodies were left piled up in the tourist area of the Boca del Río city in front of hotels, in full view, at noon.

By that time three colleagues had been murdered. Those murders had just happened and with a group we decided not to cover it: we did not know who our photographs benefited. We decided not to cover them because it exposed us. I worked for a news agency. Several colleagues were on the verge of losing their jobs as national media correspondents for not going to take those photographs.

It was a photograph that was not seen even in the war: below a road distributor, a few meters away was the beach, opposite, a very large shopping center. From two trucks they threw 35 bodies. That was an image that I did not register but that I always have in mind and that impacts me a lot, even more than if I had done it.

After the scolding of the agencies for not being there, we went out to look for police protection, photos of policemen, of the military, the luck of the photojournalist to be in the place. At that moment they opened the door of the morgue and I found that the bodies were covered up on the floor. The institute of forensic medicine had been passed. I didn’t get to the exact place, we were very scared. It was an act of self-censorship. I always say that self-censorship has saved many colleagues from death. There is a lot of stigma around self-censorship. The great purists pose it as something impossible, which should not be done. But in a place like Mexico, the most dangerous place in the world to do journalism, sometimes it saves you. It is that, sometimes, you have to wait to continue counting.

How did you think of the structure of the book Testigo de la violencia?

The first part talks about the violence that we do not see, which is embedded in some urban areas, or rural areas of the Veracruz mountain, such as the lack of access to health, education, and work. I’m not going to lie: many of these people have entered into criminal acts, drug trafficking, due to the lack of opportunities and because the drug trade offers better benefits to the people who work.

The second chapter is the “Battle for Veracruz”: I record the pure and raw violence that we lived through in those years, where the confrontations were every day, with eight executions per day. Veracruz is a territory quite conducive to crime and politics. It is characterized by being one of the main focuses for the candidates, because there are many votes: the PRI members call it the jewel in the crown. For crime we have one of the most important ports in Mexico where many chemical precursors arrive, we have a quite important migratory corridor where migrants are kidnapped for trafficking, for work, for exploitation or simply to charge a fee to move on. Veracruz is very important, that’s why the battle for the place was incredible.

But I did not want the proposal to paralyze whoever was watching it, that is why the third part of the book is a call to the organization of people, of society. We see the self-defense groups that operate in different areas to organize with society to take care of their territories, the mothers of the disappeared who look for their children scratching the ground, sticking a rod to see if there are remains of buried humans.

We have many records: we have the largest grave in Latin America, Colinas de Santa Fe.

There they have found 300 skulls and more than 20 thousand skeletal remains. They were found by the seeking moms. I close the book with a photo of Gaby, the daughter of a disappeared police officer, looking at us, challenging us: now you are also witnesses, let’s take action, let’s not stay looking.

Another of your great projects is the book Vestigios…

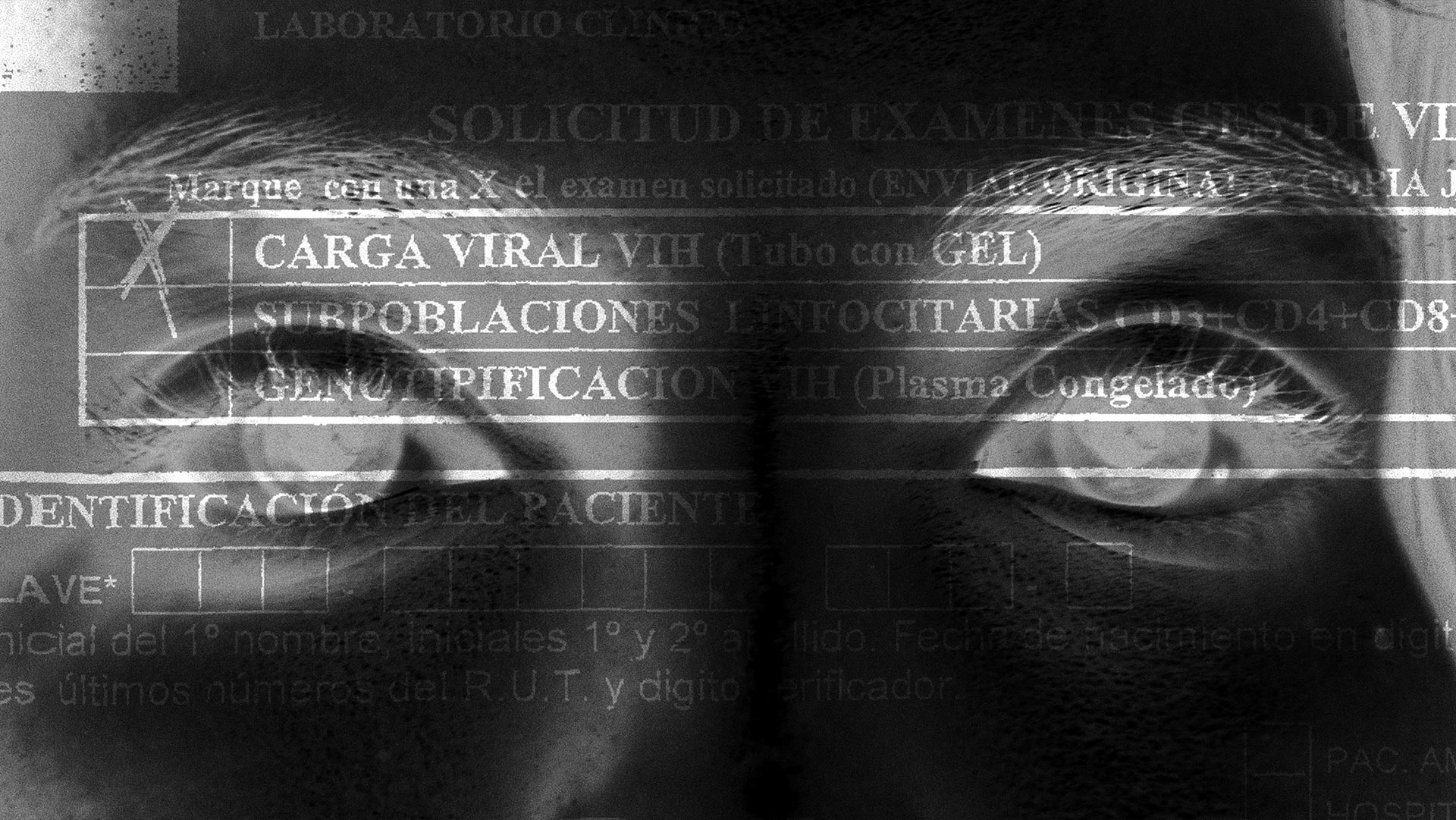

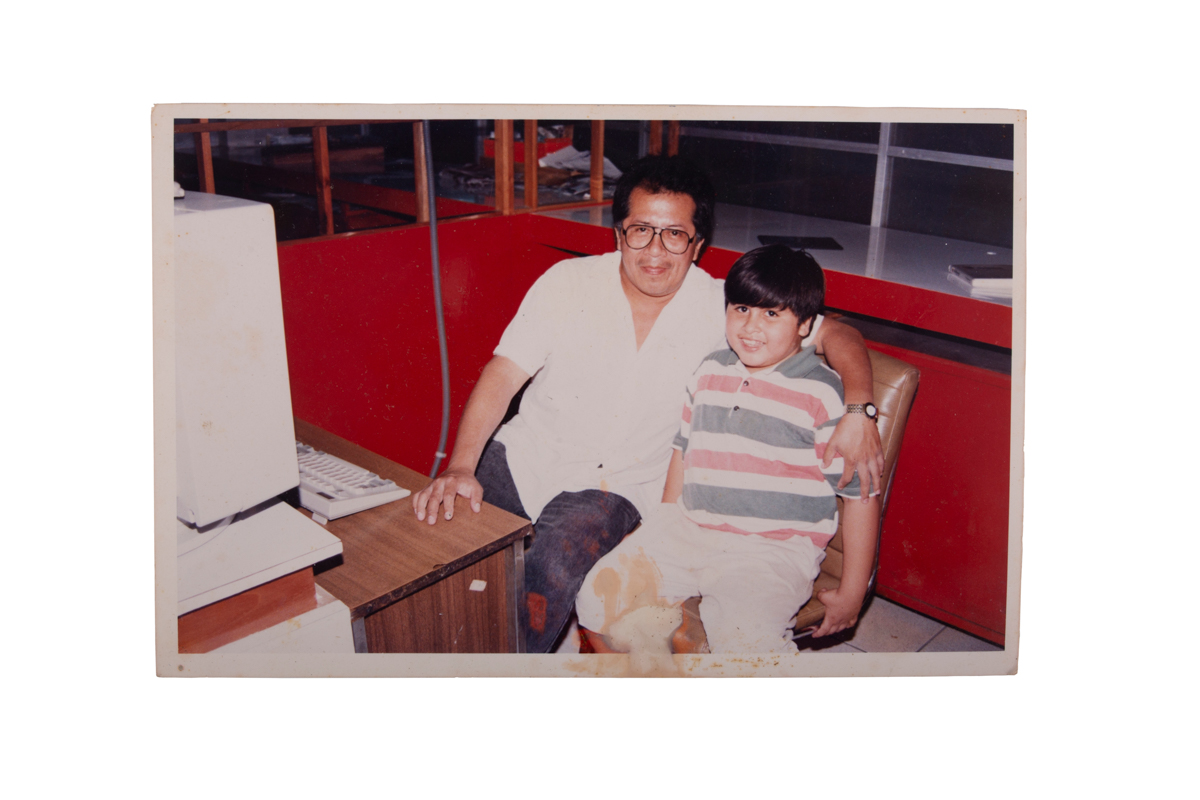

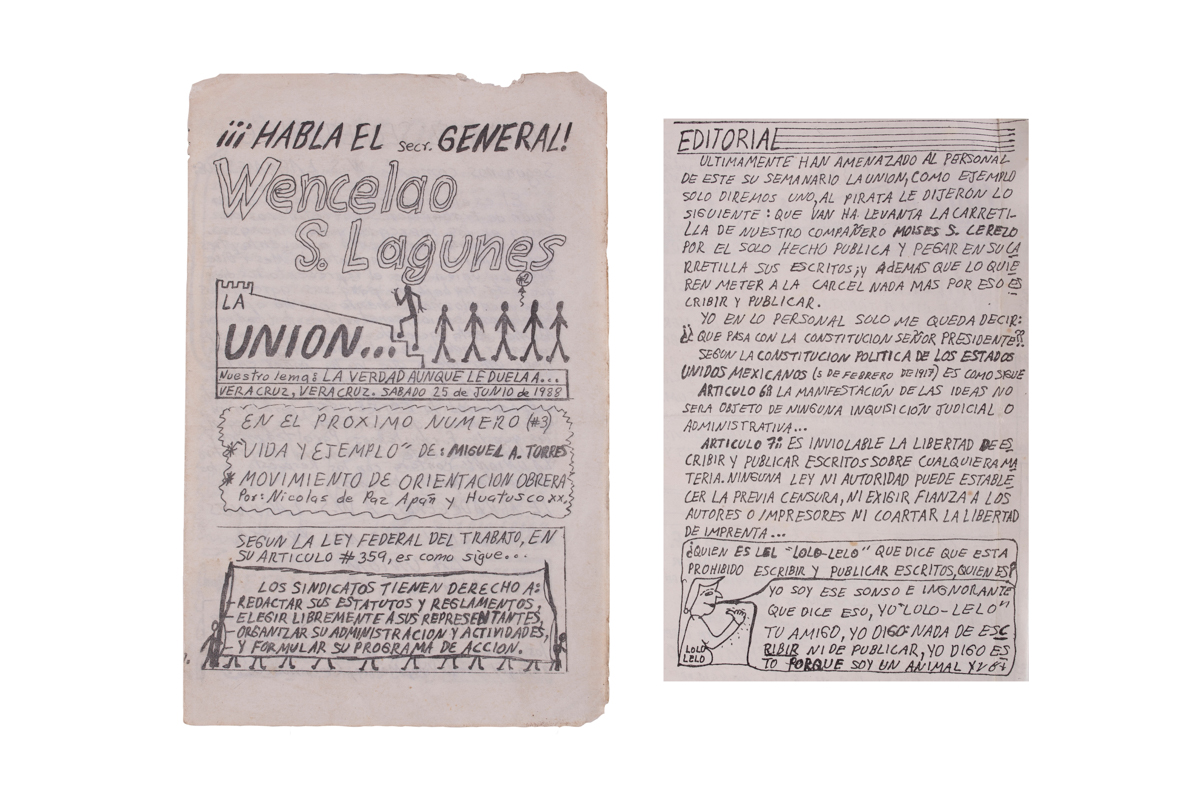

This is a personal project that leads me to introspection, to research with the families, to sit at the table with them, to talk. They are objects of fellow journalists of mine, murdered in the state of Veracruz. It emerged in 2015 during an interview with Jorge Sanchez, the son of Moisés Cerezos, a journalist murdered 5 years ago. He was talking to me about a speaker his dad had at his house, in Medellín de Bravo. He would place the horn on top of a taxi or in his house and read the news.

Moisés Sánchez’s mission was to tell, he was an activist journalist who only wanted to improve the living conditions around him. With the money he earned from the taxi, what he did was print a kind of newspaper that he photocopied and gave away. With technology he was able to do it on a computer. It was a kind of weekly newspaper, and while he was giving it away at the market or in the store, he was reading the news aloud with that speaker. I photographed that horn as the essence of who Moses was. There in that object, everything he wanted was represented, his ideals.

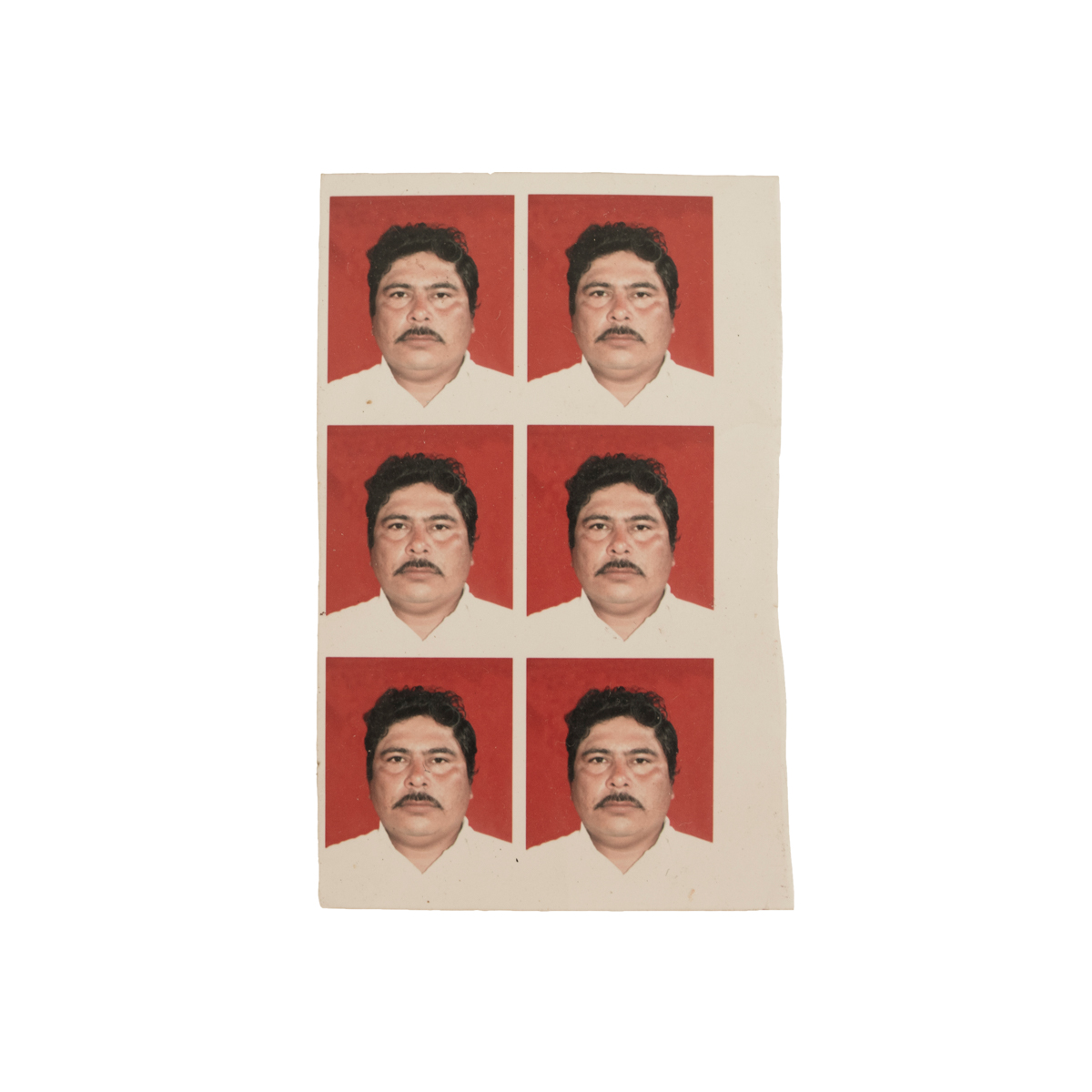

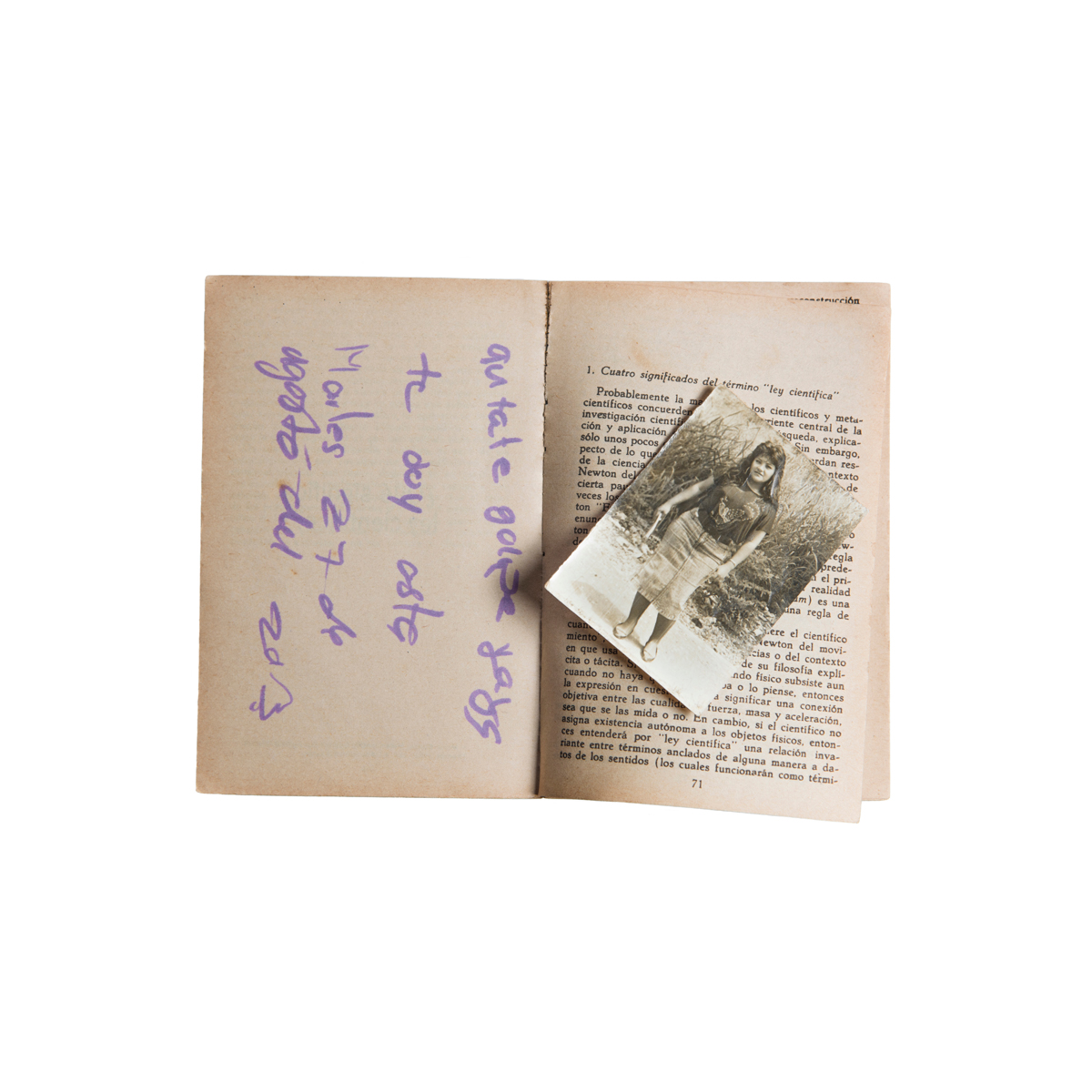

So I started looking for objects belonging to colleagues of mine who were murdered. For example, there is one that shows me a lot who Guillermo Luna was, a young man who was my age at the time: we were in our twenties. He loved reggaeton, he always wore very colorful sunglasses, a scapular, soccer shirts. I photographed these objects and also Guillermo’s credential that had been kept for a long time. You know, when you stick the plastic to the paper then it has a weird effect. You can see his face and it is the face of a child, of a young man who was killed for working.

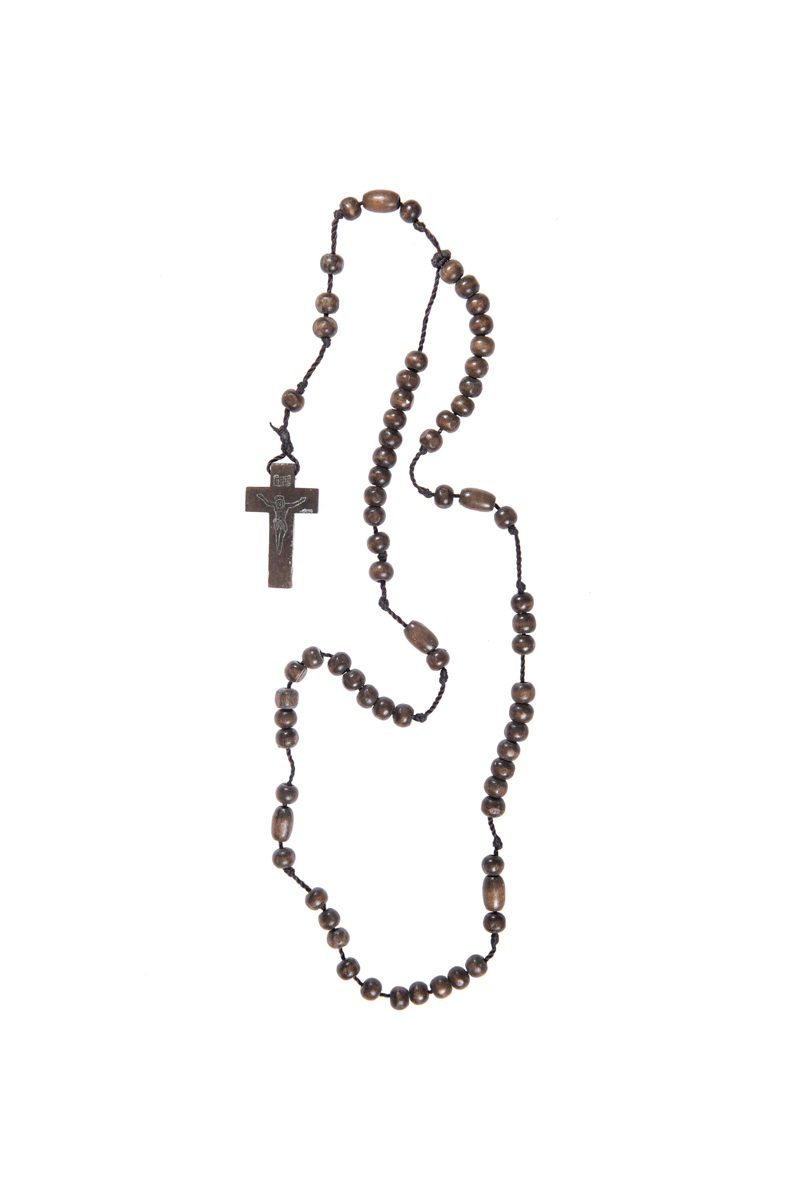

Talking with Guillermo’s family, I learned about these stories. The rosary I took a picture of was something that his mother had given him to take care of at work. These are things that can be discussed by opening the box. With Vestigios he came out. It was a kind of catharsis, for them and for me, of closing circles.

The last time I worked alongside my colleagues was portraying their funeral and I never saw them again, I never established communication again and this is something that weighed heavily on me as a photojournalist, because you have to be in the place, you have to photograph that, I had that regret. Now I want to pay tribute to them.

Did you adopt any method to photograph these objects?

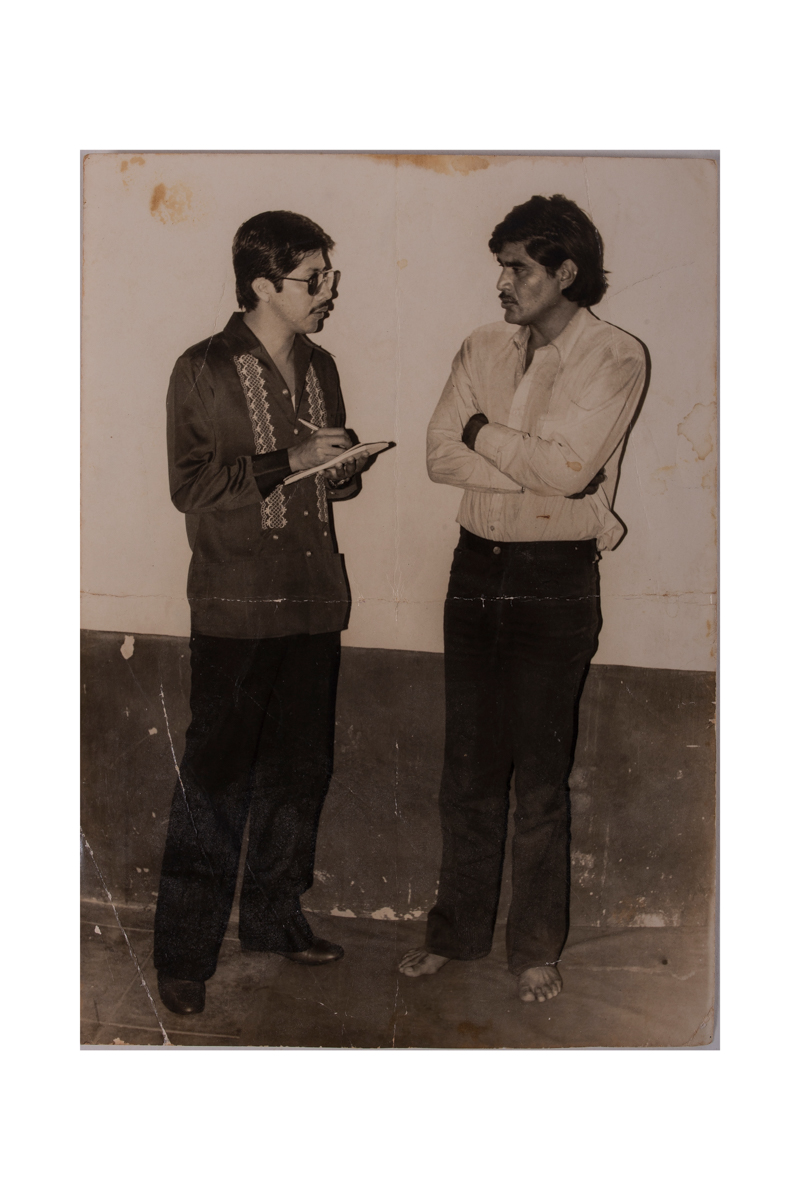

I try to ensure that the objects are as they are delivered to me, the idea is to show how they were: if they have dust, rust or are broken, I do not clean them, I do not modify them, I try to make them exactly the same. It is an approach to forensic photography. I saw a lot of forensic photography on the internet, from there I started to study a little empirically to be able to do this work. In addition to objects, I photograph archive, familiar or from work, images in which they are seen working in the field, doing interviews, for example.

Is it a finished job or is it still in progress?

Is it a finished job or is it still in progress? I’m trying to do a second part, with objects by Rubén Espinosa. So far, I have not been able to photograph it, emotionally I have not been able to do it, but I want to do it. Maybe explore journalist objects from other parts of Mexico. Rubén was my friend, he was brutally murdered in Mexico City when he fled there along with four girls. And it is difficult for me to face that, it is quite difficult in itself.

There are things that have happened to me photographing this first part that sometimes stops me. For example, the cap of Yolanda Ordaz, a journalist who was beheaded. Her cap remained in a gift box. It was given to me by her daughter. When she was photographing I uncapped the box and Yolanda’s scent was there. That made me stop. With Rubén, I still don’t dare.