“It is not about criminalizing but showing that drugs are not the problem,” says Edu León, a Spanish photographer and documentary maker. For several years he worked on migration in Europe and Latin America. And he has lived in Ecuador for more than a decade. It was there that, as a result of the triple kidnapping and murder of three journalists from the newspaper El Comercio, he began to fully understand the consequences of drug trafficking in the territory.

By chance he passed part of the Covid-19 pandemic in Madrid. He took the opportunity to register how his 75-year-old mother lived the confinement. And during that journey he remembered a fact that he had known some time ago: his hometown, in the Spanish area of La Mancha, had a very high rate of cocaine consumption. There he decided to return, to understand –and document– the reverse of the story that he began to weave thousands of kilometers from his house.

Since then he has traveled there to take photos and talk. With former consumers, current consumers and with other social actors.

How was your experience in Ecuador?

Three years ago, three journalists were killed on the Ecuadorian border with Colombia. A group of journalists from Ecuador and Colombia joined in a selfless way to investigate the issue. We went to the border, which is forgotten by the state. We met with some local journalists and they told us that the Quito media always go to the news under cover of the paramilitaries.

The important thing for me was listening to those voices of resilience, the true resilience of those people who live with the problem of drug trafficking. Later we discovered that the Ecuadorian State has a lot to do with what happened and that they all had businesses with different cartels.

For me the important thing was to give them a voice, to listen to them, especially because people are always fearing that place and the real problems there are never heard. I think that in these problems there are many grays and not everything is black or white. There is the farmer, there is the woman who “cooks” because she has to educate her children or get gasoline to be able to cross the river. It is coexistence. We cannot judge people by their environment, we cannot victimize them anymore.

And that experience in part made you look back at your place of birth with different eyes.

I think the media, and photographers too, have always been guilty of going to prejudiced places and talking about drugs through common places like blood, guns, the poor in precarious conditions. And always go with that victimizing look.

I am from a town in La Mancha. Yes, Don Quixote’s. I remembered that when I was a teenager, a news item came out about a study on wastewater from various Spanish towns. And my town was the first or second in terms of cocaine use.

I investigated and it was not just that news. There is a lot of current news that points to my people. My first intention was to go, after not going for a long time, and to look at everything with suspicion. The intention was to put those headlines under the photos I took. Then the subject developed further. I spoke with the association of ex-addicts that had just been created and, of course, there are many problems. There is a large part of the population that consumes and there are even 14-year-olds using heroin.

I was going to work with the association of ex-addicts and I was going to give a workshop so that, through photography and writing, people could interpret their emotions. It was cool because the idea was that my gaze and his would be shown in the town and have a week of talks and debates with all the information. But there are people against talking about it. For example, parents began to complain in schools against drug talks and stopped giving them. That is the level of hypocrisy that exists in consumer issues. We see crime there and here we are not guilty of that.

How is the town?

The town is an excuse to talk about this. We can say that it is a place in La Mancha whose name I don’t want to remember, because it could be any town. It is a more or less large place, it has 20 thousand inhabitants. It is a town that went through agriculture and now has more industry. It is on the route of El Quijote and there are even windmills. He identifies with that: the mills and Sara Montiel, who was also born in the area.

Yesterday I saw in an exhibition of Magnum, of bodies, and there was a photograph of Cristina García Rodero of one of these places in Galicia. There was a photo of a man on his knees taking off his guilt and a woman who looks at the photographer with contempt, as if to say: “this is the guilt that we carry but in silence, you don’t have to come and look at us.”

It is a bit what happens in the town. We all know this problem but it stays here and it is not talked about. I think that’s the problem and there are more than 70 percent who have ever tried some type of drug. It is a very, very high rate.

How are you working?

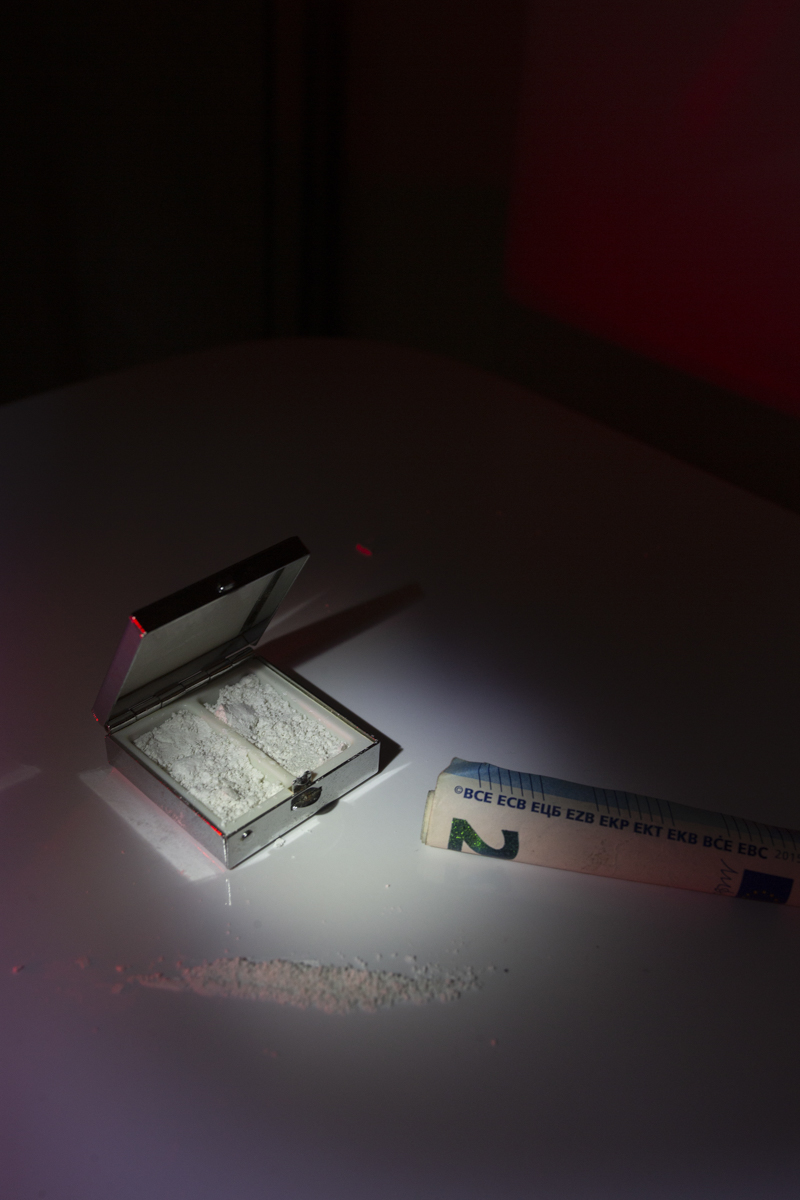

It is very difficult to be in consumer environments because due to the pandemic, consumption has changed to a more private form, to the intimacy of the houses. It’s difficult to document that in this context. So I am working from a more symbolic place and a more journalistic one.

I interviewed an elderly lady who talks about drugs since she was unaware of it. Also to José, who is from the association of ex-addicts, a very hard testimony. And I interviewed young people who use the drug with information and are more responsible.

I also wanted to speak to the civil guard and municipal police, but they have already taken my word away. I tried with the priest, he said no. It seemed interesting to me how the priest in the villages is the representation of guilt: the confessional is a great creator of guilt. But hey, he said no.

What is it like to return?

I spent all my summers there. My father died when I was seven years old and whenever I go to town it is that “you are just like your father”. Now I came back in an unexpected way and found it strange. I’m neither from here nor there. I see some friends from town who are people who keep getting up and their mission today is to go to the bar, drink alcohol and get high.

It’s not that I’m totally oblivious to that life. In Ecuador I used cocaine, it is very cheap and I did it once or twice a year. When I did, I used it destructively and this work has a bit of self-criticism. It is not that everyone has drug problems: of 100 percent of those who use drugs, only 10 percent have a problem due to drug use. For me, consuming cocaine politically entails a lot of death, and that has more to do with the war on drugs than with the drugs themselves. That’s the point: drugs are not the problem. The problem of who runs the business.

Is it public in the town that you are doing this work?

I was frank and I think that has played against me but hey, I wanted to go in an open way. I don’t want to show only what I see, but also the research and the talks that I have with different people.

I think it is important that there is an open space for dialogue, which is what we need. Because of a ban, the young person will not stop using drugs, but if he has information, he will be more responsible using it. If you say to a young person: “Look, these are the drugs, these are the consequences.” They are not stupid.

What would you like to achieve with this job?

Sometimes, we, photographers aspire to things that are out of our reach. I’m not so interested in publishing but in creating a space. I think that, in photography, we have to stop thinking of ourselves as a firm and start generating multidisciplinary spaces. In the town I contact sociologists to talk about drugs and create a space for dialogue and understanding. That is my aspiration.