Peruvian photographer Victor Zea wakes up early because light enters through his window. It doesn’t bother him: a few years ago he stopped covering it because now he communicates with the sun. He contemplates it, takes pictures of it and strikes up a conversation. Victor was born in Lima. His Quechua father transmitted his ancestral culture and his love for photography. As time went by, Victor discovered that there was also a kind of personal search in his work. “I managed to get closer to a root, for me it has been an interesting process. As an authoring process, it made me feel like I was on the road”, he says.

He defines himself as a “street photographer”. For him, photography is a channel that opens the doors to discover the world. That’s what he thought about when he started studying and also when, in 2010, he traveled as a backpacker. At that time, he did not have a clear objective: “Photography was an excuse to meet other people,” he says. This is how he became related to the sun, the hip-hop community and, now, with the rainbows.

The book in which he explores the role of the sun and the shadow in Cusco is called P’unchaw, which, in Quechua, means “Light of day”. From the old Inca capital, Victor affirms: “They stole the gold, but they did not take the sun.”

Why the sun?

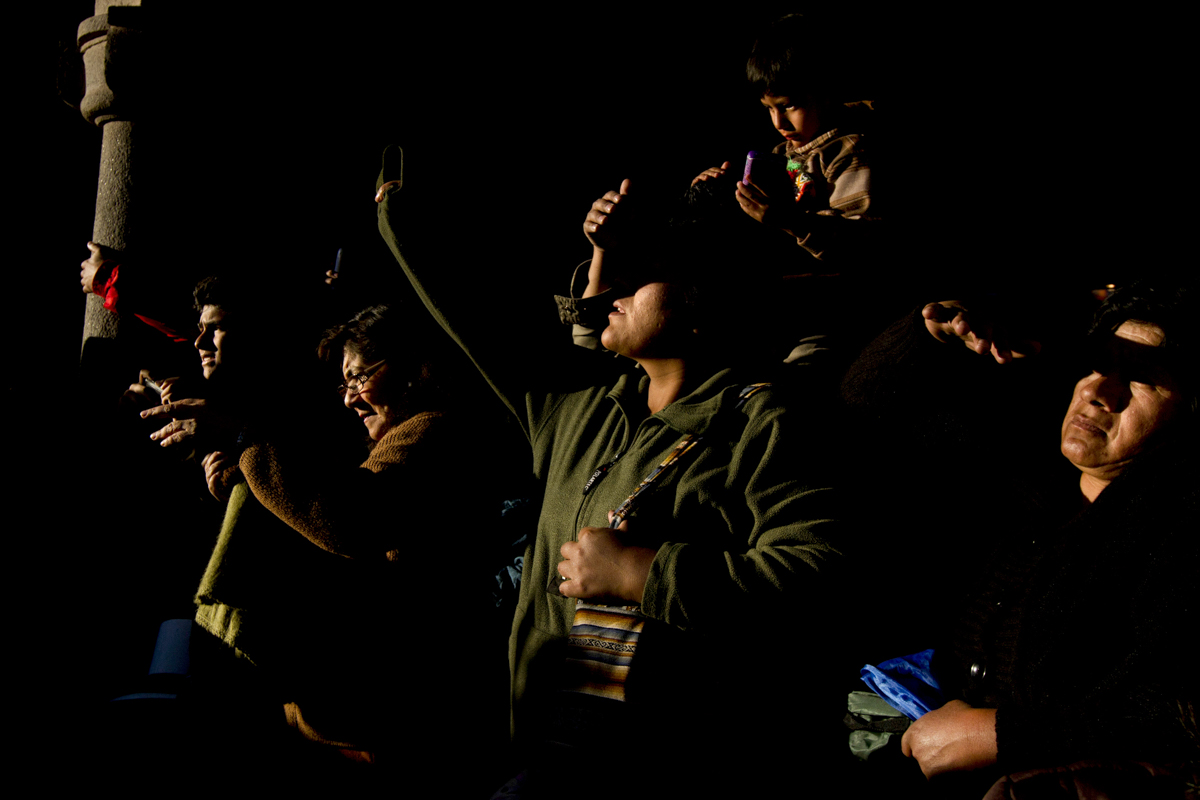

In the Central Square of Cusco there are some portals. The first thing that caught my attention was seeing how the light enters those portals, enters and leaves. At that time it was not clear to me, it was simply something that caught my attention: I was interested in the characters, they seemed to float. I was playing with that aesthetic for one year on that block, just on the portals. The interesting thing about the project was when it stopped being form and began to gain substance: talking about light and depth in Cusco was not simply an aesthetic.

Certainly there are many myths that connect the Incas with the sun…

When I started working in 2013, everything was super repetitive, I always found the same thing. Then I read myths that turned me on and I began to understand how the ancestors were observers. The Inca culture has had an understanding of light and shadow to create the space in which they are. Furthermore, in an Andean society like the Inca, the sun was its maximum identity that regulated the social, the economic, everything.

There I investigated how those great astronomers see Cusco, like a solar clock: they built temples knowing how the sun was going to rise on certain days, all managed from the incidence of light and shadow. All this aesthetics raised other questions for me and I began to photograph equinoxes and solstices.

I read that one of the topics that guided you was archaeoastronomy, that is, the study of how the populations of the past “understood the phenomenon of the sky” and what role it played in their cultures… Is that so?

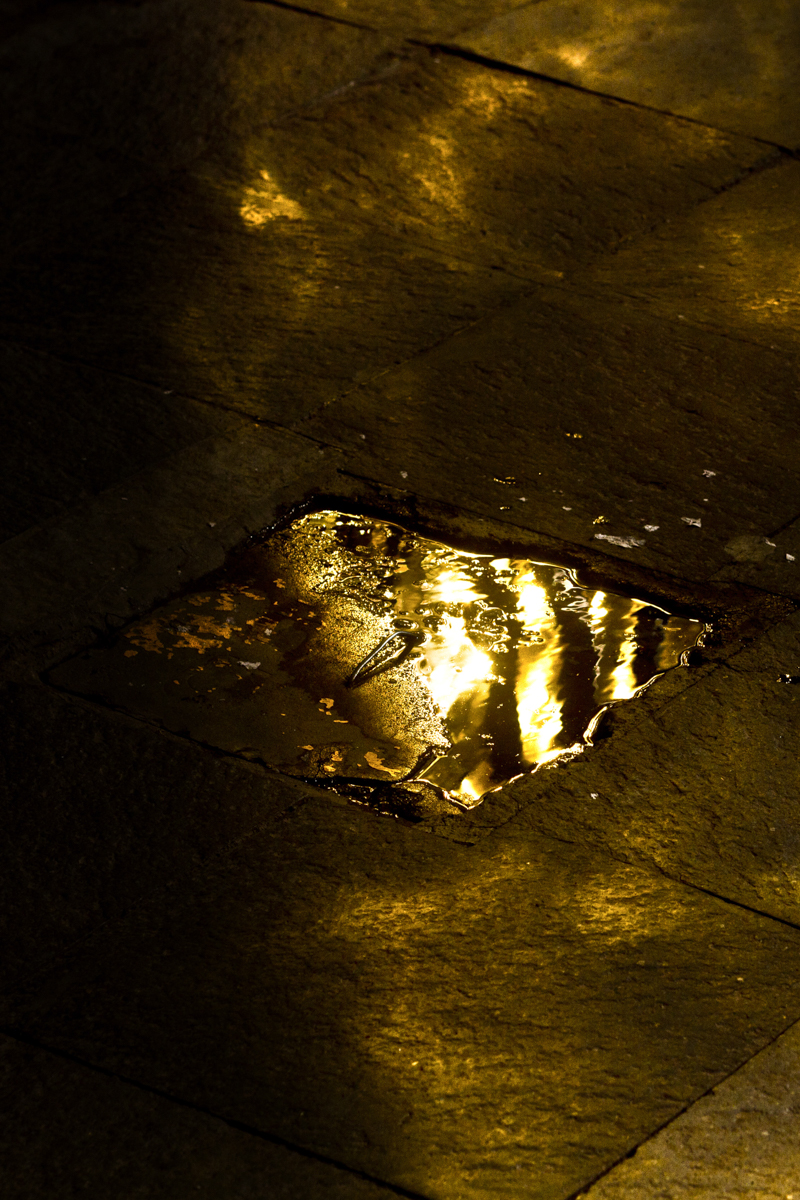

I photographed at specific times: I knew that at 1:15 p.m. the light went out on one side and at 3 on another. So I was having a schedule. At the same time, I started reading more about solstices and equinoxes, their impact on life. I was finding these forms that they had already created, they were sculptors of light and shadow. So you realize that it was a calendar city. Cusco is shaped like a puma if you see it from the sky; at the winter solstices the first ray of sunlight falls on the puma’s tail and the streets light up. I realized that light and shadow were not just an aesthetic but a light and form that revolved around this city. The sun will always be there, we are passengers.

You named your photobook P’unchaw in honor of the myth. The text says: “It was the name of a golden idol, of the most venerable relic and deity of the Incas: the statue of a human figure located in the most sacred temple of the sun in Cusco.”

Qoricancha -the main Inca temple that was destroyed by the Spanish- was formerly called Inticancha, and there the sun and different gods were worshiped. I photographed that space because it was clear to me that I wanted to talk about the sun in Cusco. On visits to the temple, I first heard the myth of P’unchaw. There was an anthropomorphic gold idol that represented the sun.

I begin to see how the light or the sun turns into gold and what gold means to me and to our ancestors. There is also a game with extractivism: they stole the gold but they did not take the sun. Today people come with the best intentions to understand a worldview, but they fall into this extractivism. It is very shocking to see this mass tourism and very strong consumerism.

The book begins with a supported goldenrod: it is the representation of the foundation of Cusco. Like all myths it is unverifiable, but one of the things that I rescue for me is to meet an Andean and living culture. There are people who believe in the sun, who speak to the sun, who speak to the rainbow, who speak to the rain. It’s a dose of that fantasy that they create you as a child and then break you, but it’s still alive. It’s super crazy for me. After a year, I was talking to the sun, I was trying to have a relationship, I was looking to break with what they generate in your mind. It is not that you have to understand everything, some things are not understood.

As a creator, the process was interesting, I began to blend in with that light, and to create my own convictions regarding a worldview. I could say it helped me to believe.

What are you working on now?

Now I am working a lot on the rainbow in its different meanings. If you point your finger, your finger will rot. Or that you have to cover your mouth and that the rainbow makes women pregnant. Those are not so well known myths, and you say: “this is impossible”. Until you meet people to whom it has happened. Then I begin to have this interest in myths or ideas that end up being something that is not true. We grow up not believing and it is real, it is there, it is part of our own life.

Is there extractivism in photography?

I have grown up with a vision of western photography, although my first references were from here. My way of seeing has been fed by that colonialism as well. It is already a matter of how you approach personally, it is very difficult. Currently, the author has a higher priority to create in a more inclusive way. You should not go, photograph and leave, but it is part of what happens.

I have felt this way many times, imagine. The most complicated thing for me is when, for example, I photograph the hip-hop community, who are my brothers, who are my friends, I strike with them. But in the end I am always Victor, the photographer who is watching them.

And how was that approach to the world of street music?

A friend had an underground cultural house where different collectives of hip-hop, theater, photography, a well-defined social political culture met. It was like listening to underground idols by mp3 and suddenly I had them next to me and they were my friends. It was a synergy of street photography. For me, personally, who was born in the middle class and in a family that has been super protective, photography and knowing this world represented freedom. Photography allowed me to know other realities, I have had the opportunity to meet incredible people. For me, it was: “get out of your bubble and know what the world is”.

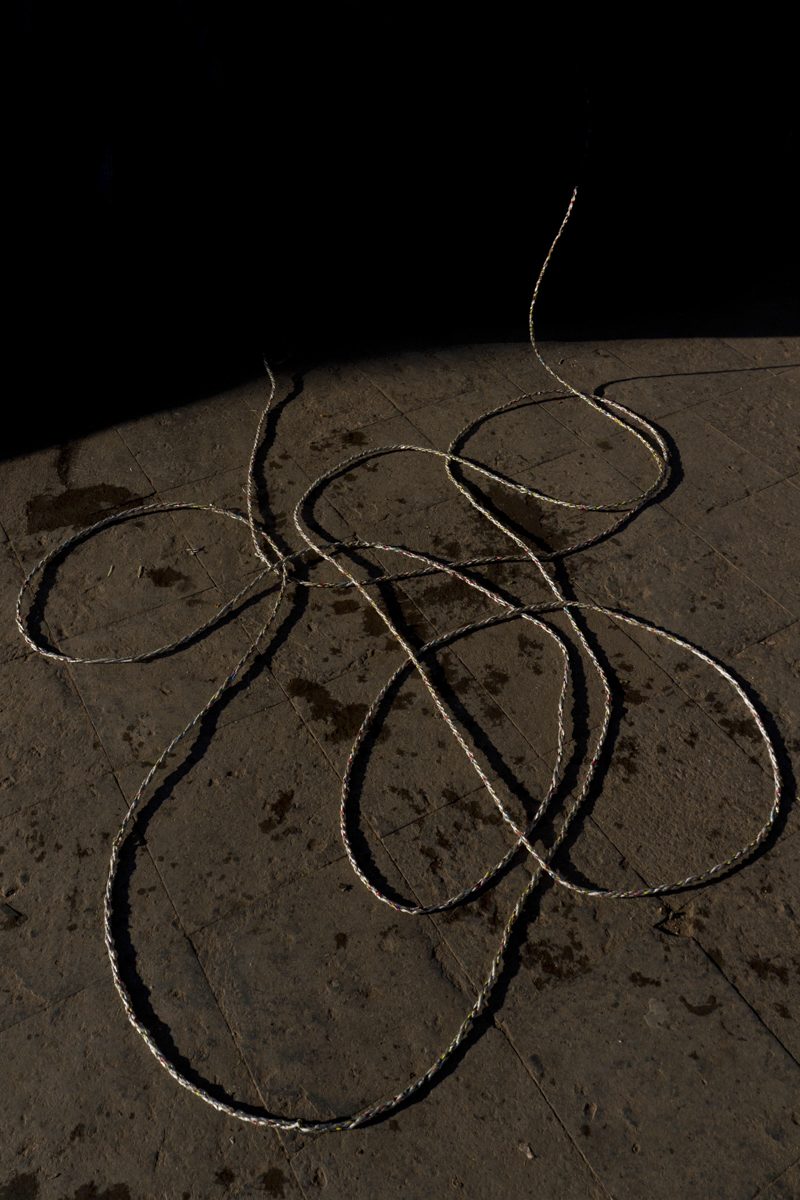

How did you choose to get into the hip hop world in Quechua?

In P’unchaw’s book, the process involved thoughtful photography, the composition well placed. I have waited two years for a photograph that did not appear. At work with hip-hop a friend told me: “hey but hip-hop is not neat, rap is telling the president ‘fuck you’, it comes out of the gut.” So I started to play with musicalization, how it is used to create songs, where sampling is used a lot, it repeats three seconds of a song and you repeat it again. I’m creating a more musical transition, closer to the style of hip-hop. It is a work in progress.

So, in the same way, I started cutting my files of the hip-hop scene and from one photo, I get ten. It was a liberation, as an author’s process, to leave the neat photograph. I was deconstructing the way of making images and when I got to freestyle it was like glory.