“We cannot condemn photography to only seeing the present and what the eyes see. We should allow it to imagine the world”, says the Colombian photographer Jorge Panchoaga. Son of a mixture of an indigenous family and an urban peasant family, in addition to photography he studied anthropology and, even though he never practiced it in a formal way, he acknowledges that it nurtured his gaze. The worlds that Panchoaga imagines are not abstract daydreams: his works range from ethnography to science fiction, from historic investigation and intervention in public debate to the exploitation of dream territories.

In addition to working on topics such as oral memory and human relations with nature –his best-known multiplatform project is Dulce y Salada– Panchoaga is one of the managers of the platform Drogas, Políticas y Violencias, where there are four of his visual essays. One of them is Historia natural del silencio, investigates the stories of Colombian men and women crossed by the world and the experiences of what is illegal in Colombia. The other works portray different aspects of coca leaf cultivation and the peasants who grow poppies. “What in some spaces or towns or social lifes is a sacred plant, a food or connection with a larger explanation of the world and of life” he says, “others see it from a simplified logic of conscience and market. For some it is a drug and for others, an universe”.

Is this contradiction what unites all your works?

I try to navigate this paradox by deepening in each one of these scenarios, regarding the connections, the divisions that exist, the gaps, the misinformation and, above all, trying to break the links that simplify and stereotype the forms of explain each one of them.

Drug policy is approached with a single moral and restrictive gaze. In this sense, my work seeks to get away from the easy explanations of the type “coca is equal to cocaine.” Coca is a plant that has been cultivated for centuries in different cultures and there is a chemical process discovered in the 19th century to extract the alkaloid with which cocaine hydrochloride is obtained. This chemical process seeks to synthesize one of the components of the plant and, from that discovery, a new timeline and historical events begin.

The use of the plant in the market has different moments in history: there were moments of legal consumption where there is a record of a pope and at least two former US presidents who were addicted to the alkaloid due to the consumption of Mariani wine that contained it as one of their components. The same happened with Coca Cola: within its components it had cocaine. It was after many years that the consumption was banned and the path of stigmatization began.

With the prohibition started a new logic of persecution but, again, it was based on one single perspective of all the multiple perspectives that it has. The coca leaf has been understood in many ways over the years, through social, mythical and ceremonial spaces. I think is time to understand historically and socially what has happened. It is also about entering intimacy, both rural and urban, and trying to understand what are the causes, the results. It is breaking the moral and the “good” or “bad” that exists around it and, rather, see it from other points of view.

Has the anthropological gaze influenced your work?

I am an anthropologist, it has served me a lot, although, I have never signed a contract as an anthropologist. In some way, my vision is marked by anthropology but also by family dynamics. My family is indigenous. My uncle, Luis Panchoaga, was the shaman of the family and he organized spiritual and ritualistic meetings in which we sat down to mambear, that is, chew coca, and talk. That was part of everyday life.

For years I was my uncle’s disciple. In the family dynamics, I was the one with the most characteristics to be the next witch in the family. At 21 or 22 I left. I basically said “this is not for me” and gave up what could have been years of training. My gaze is made up of all those things.

Once, like everyone else, I was a fan of music bands. The singers that I liked the most wrote their lyrics. I would be 13 years old and in the interviews they said: “I write about what I have lived.” In photography and in many things the same thing happens. Even science fiction is made through what we have lived and what we are. This is a dialogue with all the issues we work on, the people we know and in this dialogue the project and us as people are transformed. All my projects have this dialogue between what I have lived and what is happening along the way.

The works about coca and poppy have a look that rescues the natural, the beauty and almost no violence is seen.

I began to photograph this topic because of Guillermo Ospina, a friend who was my professor in anthropology. One day he said to me “I’m working in a zone of Nariño, in the zone with the most poppy crops in the country”. He invited me to do a work together. And I accepted. One day we left in his car, when we arrived I already had some ideas in my head. We had talked a lot about the topic and I had read a lot about drugs and drug trafficking, between ethnographies, news, theory and the classic stories of violence. There is a book that influenced me a lot: El truquito y la maroma, cocaína, traquetos y pistolocos en Nueva York, by Juan Cajas. It’s basically, one of the most interesting works I have read, with a very long reflection on drugs.

The first thing I proposed to Guillermo was to do a very peaceful work. My idea was to go, talk to the families who were farming and understand that this was their family economy. An economy of these contexts where people came from other regions and buy opium gum. They cultivated, harvested and lived on that. I was interested in how the day to day was constituted, beyond the big business of drug trafficking.

This logic is implicit in the rest of your essays.

It could be said that it is a way of looking at some aspects of these issues. When I traveled to Bolivia to do a work on Coca in the Yungas area, I had a lot of interest in the subject. I traveled thinking about what I learned with my uncle, my mambeadas and what I understood of my experiences in Colombia. After starting the project I inquire about the history in Mama Coca, which is a classic book in the research on coca in Latin America. I also read other books and began to reconstruct the economic history and of the coca leaf: the wines, the syrups as remedy, Coca-Cola, Mariani, etc.

I began to see the advertising posters of the time: I made a compilation and then I read about Bolivia and the Yungas zone. I was traveling to work with Afro-Bolivians who live in this area of the country and who have been cultivating coca leaves for centuries. Their connection with the coca leaf dates back to the first enslaved Afro-descendants who came to work in the mines located in the upper parts of the Andes in what is now Bolivia, the change of altitude and the forced work generated a lot of deaths in this population. The solution of the slaveholders to avoid the lost of more enslaved people was to take them to the lowlands, to the haciendas where coca leaves were grown to work there, not because the Spanish thought that the traditions of cultivation and pijchar should be maintained, but because without coca leaf there was no mining and without mining there was nothing to take to the kingdom of Spain.

There is a deep connection between the mining work and the land, the strength that the coca leaf gives, the social dynamics, the rites of giving an offering to the earth with the coca leaf for the spirits that are inside the mine. Let’s say that the coca leaf is a whole in that context. It interested me a lot, but also I was interested on how the relationship was now, what links and bridges were builded over the years between the Afro-descendant communities from the Yungas zone and the coca leaf.

What did you find?

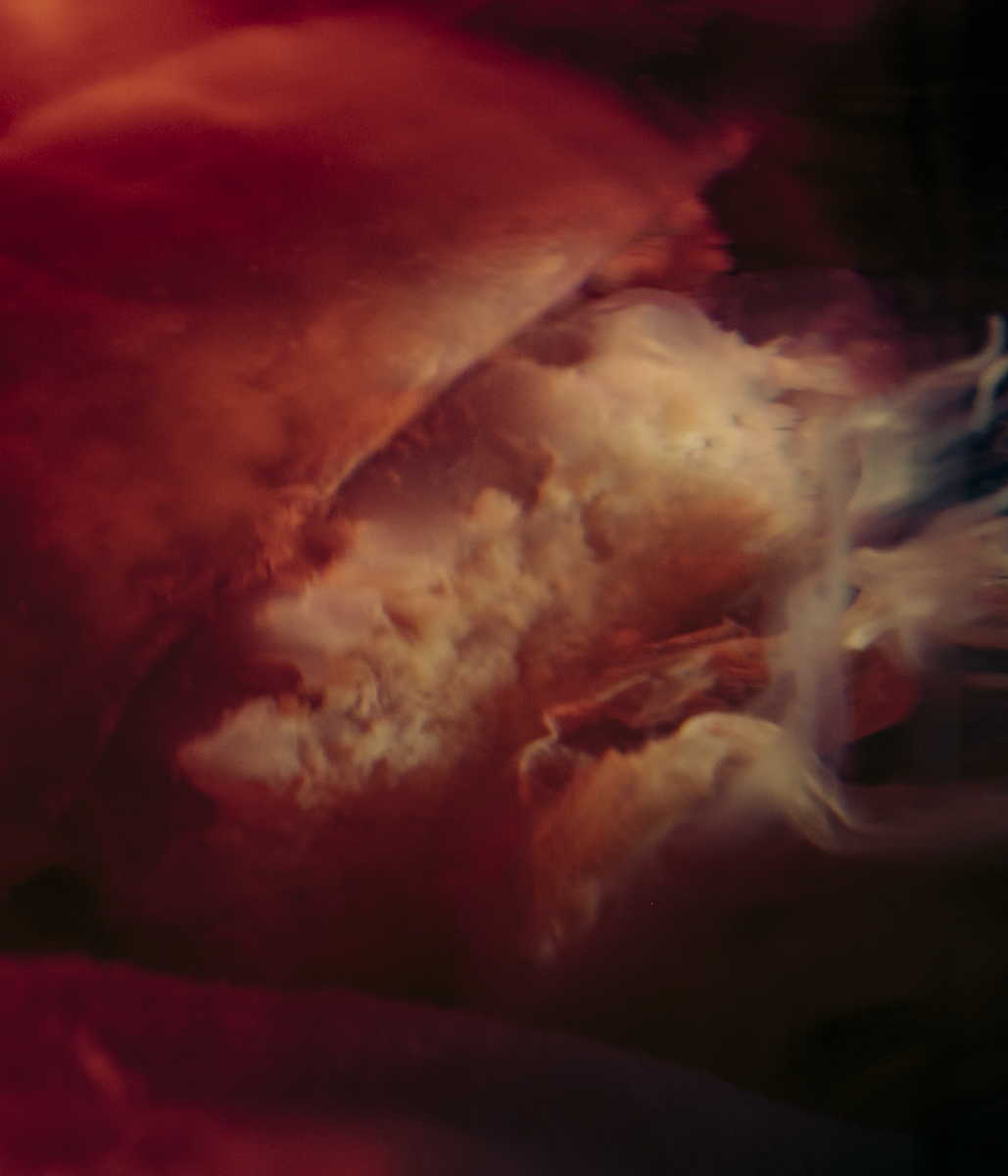

When I began to photograph I found some beauty subtleties in the language, which for me were like doors to other ways of understanding. I remember that someone told me “you are from Colombia? There the leaf is for the foot ¿right?, not for the mouth”. That little narrative set up an interesting abysm in the logic of the coca leaf production. They were referring to growing coca to produce cocaine chlorohydrate. If you have seen the photographic projects, the news, the European and North American documentaries about how is produced the cocaine base, you will have seen that the leaf is roughly harvested, the leaves are torn off with their hands wrapped in rags or ribbons, sometimes the plant is stepped on, the feet are placed on the trunk and the leaves are torn off. After being harvested, the leaf is thrown to the ground, watered with gasoline and other chemicals, stepped on, cut. I suppose it was that way of treating the coca leaf in the laboratory that he was referring to. There is a relationship of aggression, almost of outrage on the plant in this production process.

This phrase was told to me from the people who legally grow coca leaves for consumption in Bolivia. For them, the relationship with the plant is different: harvesting has another meaning, it frames other dynamics in the relationship with it. Women are who, most of the time, go in groups to harvest at different lots and everything is more delicate. When I accompannied them, I notice their delicacy to pull each leaf from the plant, you could hear the sound when they removed a leaf. There was a respect for the plant. There is a world around that.

Is a narrative subtlety but it points out different positions, and in the middle there is an abyss. In the phrase that person told me, the comparison level was very aggressive, but emphasizing the difference helped me to approaching the work. It does not mean that in Colombia there are no communities with a connection of this type with the coca leaf, there are. But the iconography of the Colombian narco narrative is like capitalism, it transcends borders. And stepping on the plant is as if when you get to eat, you kick the table and if the plate is cold I throw it in your face. This and other stories made me think about work in other ways. I try all the time to imagine what I hear and, listening almost always, I try to understand how I can talk about what is not seen.

That is something we wanted to ask you: there is a very strong relationship between your way of photographing and the dream world.

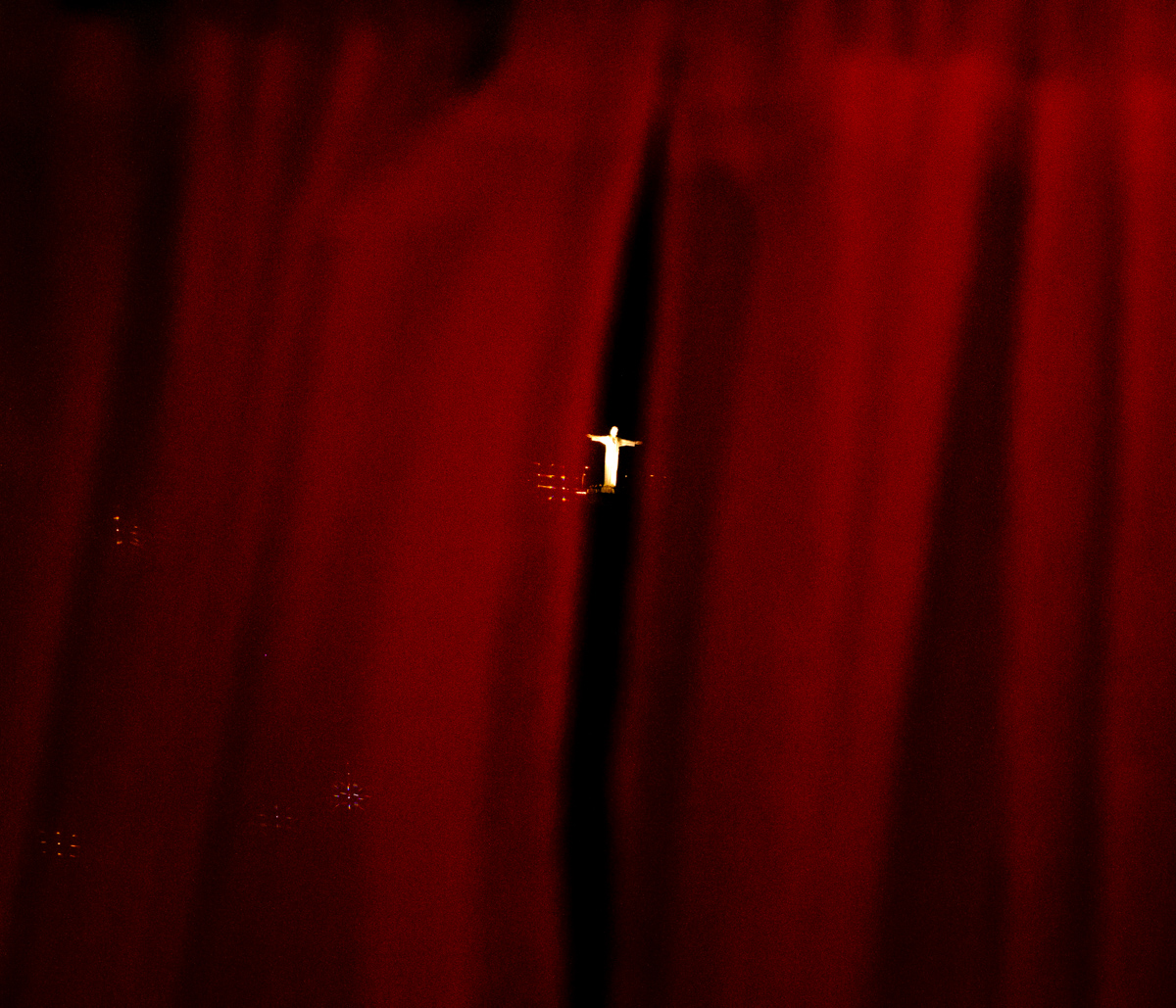

Photography has a enormous limitation, and it is that, basically society has tried to restrict it to registering what can be seen, what is “real”, what is there, in front of the camera. But the realities, n many settings, are made up of things that cannot be photographed because they do not exist in the material sense but they are there. Photography should be able to account for that. The public and the male and female photographers should give this freedom to photography: the possibility of trying to portray what is not seen, to imagine the world and colonizing the future, to look for a space of imagination to say “this also belongs to us”.

Inside these subjects there are many things that cannot be photographed. When I chewed coca, when mambeaba, we talked for hours, but the trip happened when I closed my eyes and I listened my uncle singing. There I could go out and fly, go to other places, feel myself in other forms. When I dreamed, I was trained to fly and like this I learned to be conscious in my dreams. I learned to go and come back from those trips and dreams and that has no way to be photographed, but for me and my uncle it exists, it is there. As for many communities, the bridges that weave their sacred plants are doors to other realities. You could not believe it, but for a lot of people it is part of a cultural frame of their reality. And I think there is a complex gap between what photography can and it is accepted to do, what the viewer wants to read and what the photographic industry consumes. That is a dynamic where I consider that more and more we must defend the possibility of imagining from photography, of trying to portray what is not seen of our realities, where we understand that contradiction of these times. The oneiric in the image to understand reality in its complexity. We already realized that only by portraying what happens we cannot understand it. In this sense, every time I see more photographers dismantling those borders and pushing with their work the way to visualize what is seen and what is not seen.

Did this happen on other projects?

At Historia natural del silencio, everything that happens is from a time that has passed. I went to 1980 and 1990 and I collected stories of people who, at that time, were childrens who grow up and have some relation or story that is related with the world of drug traffickin. That cannot be photographed in the present. So, what I did was to build an imaginary city, or many. There are photos of Popayán, Cali, Medellín, Bogotá. The people inhabit those places and I take photos around their histories, but the project emerges from trying to build imagined cities.

What is this project about?

It has to do with how the Colombian society, in different moments, was permeated at different levels by drug trafficking. When it was not ethically judged on a social level, there was a certain permeability in which people were part of those jobs and many families grew up in everyday life that had some kind of interaction with this world: drug trafficking generated, and it is worth saying, a lot work and as in any industry required labor. For a part of society it was configured as work.

When you talk to different people in Colombia, in the past there is always someone who had an acquaintance, a cousin or a friend of a friend, a neighbour or the father of one of the schoolmates who work as pilots, cooks, or lavaperros as is called someone who is a driver or a messenger. Those stories are there, in a subconscious silenced by the moral and the ethics of today’s Colombian society. As heirs of good manners, we silence the problem but we don’t solve it. And as a result we have hundreds of never-told stories floating in the silence of hundreds of people. I have tring to collect them, doing the exercise of listening to them to photograph in the present, everyday life that had some kind of interaction with this world: drug trafficking generated, and it is worth saying, a lot work and as in any industry required labor. For a part of society it was configured as work.

In Popayán, the stories of many friends, acquaintances and even distant relatives have to do with this. The same happens in Cali or Medellín. In Bogotá it is more diffuse because people come from many places. The people understand that: you can’t talk about this, their own stories. That is whatHistoria natural del silencio is about: the natural way we learned to keep quiet about this part of the country’s history.

What is the framework that ties these stories together?

All this, in a way, frames the ways in which I try to reflect on the problem, on what they call “drug policies.” The abstract “drug policies” is an idealization from the state apparatus and from the governments to fight against drugs, but this idealization affects the people’s everyday life. It is so called because they are the guidelines on which programs and actions are carried out on reality. But of course ideologies, interests, and above all an assemblage about the present and the future are framed in these policies, that is why there is the debate, a debate about the narrative and the way of understanding the drugs issue. The debate is there, although the effects are generally on the most vulnerable populations, the results are in daily life: the dead are buried every day, the prisoners stop seeing their relatives; shootings occur and there are children in the middle, junkies are still on the street or with health problems. Thinking about other policies and other narratives is also transforming the effects on reality.

That is why the labor of rethinking reality and revisiting what happens with issues such as poppy, coca or even our collective unconscious. We are trying to understand these connections, to see how these logics of discourses and policies have and have had effects in reality, but also to understand that current drug policies are unable to comprehend all the nuances and realities that coexist today in the field of drugs.

Structuring a narrative, speeches and policies that, at least, are discussed by society should be a priority for a region like Latin America. Also, that they can be seen through the logics of scientific research into the results of the war on drugs, the symptoms of today’s society, something that goes beyond the moral and that a much broader discussion and healthy can be sustained.

How was the creative process?

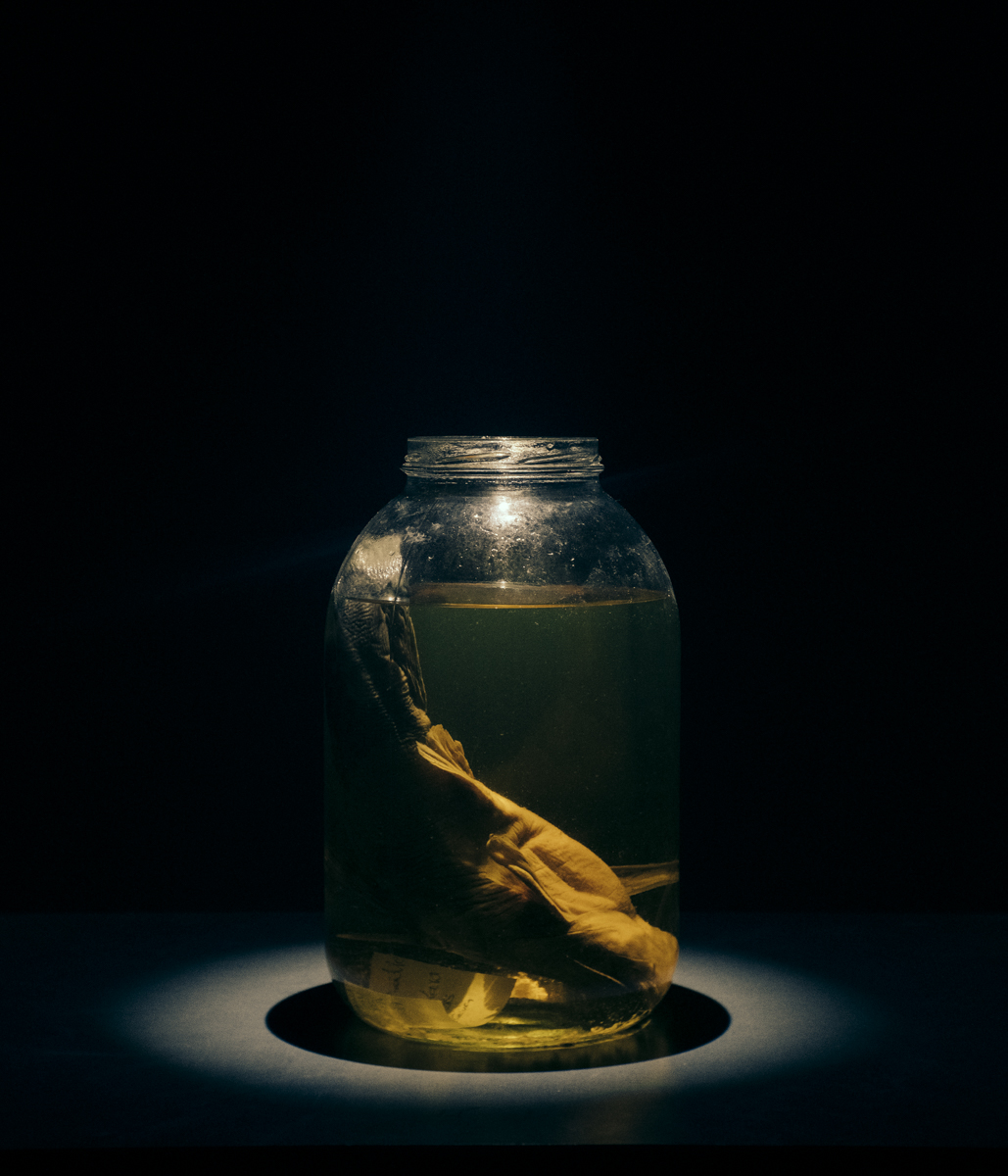

I started reading literature by different authors: Juan Cárdenas, Pilar Quintana to try to mentally create an atmosphere for the project, then I instinctively traveled to Cali and started photographing natural history museums. The museums took me to the taxidermists, the taxidermists made me find a very particular object, whose story I tell as an anecdote because I have not been able to verify if it is true. A taxidermist I met at one of the museums told me a story about a horse that he was commissioned to dissect. According to what he told me, it was Terremoto I, a horse that belonged to Pablo Escobar. The story of how his skin got there, the photos, and why he was never picked up and stayed at his home is fascinating. The horse had never been photographed: he had allowed it to be seen by some onlookers but never allowed it to be photographed. After two days in the museum, he invited me to his house and allowed me to see and photograph it. From this horse the project took an unexpected turn, took its own course.

There is a moment when projects take on autonomy, life and begin to demand actions, like a living entity. It happened like that. I started to collect stories around this topic, suddenly I got into the taxi and the driver told me a story about the subject, I went to a cemetery and another story appeared, I sat down to drink beer on a balcony and another couple of related stories came up. After traveling through the southwest of Colombia I returned to Cali and in compliance with an invitation to have lunch at Marti’s house, and on the recommendation of his daughter Marcela Vallejo, the book On the Natural History of the Destruction of W. G. Sebald fell into my hands.

When I took it in hand I realized the connection between the title and the project. I realized that very naturally we internalize silence in those stories. Nobody says it, because it is known that nobody is going to want to have anything with you, they do not give you jobs, the US visa is blocked and there are many things that are coming your way; but that story is there and people learned to shut up and build a system of imagination of alternate stories to explain how such a character in the family died, in which such another was working. For example, “they didn’t kill him, it was an accident”; “it wasn’t this, it was that”; “he didn’t work in that, he was a trader.”

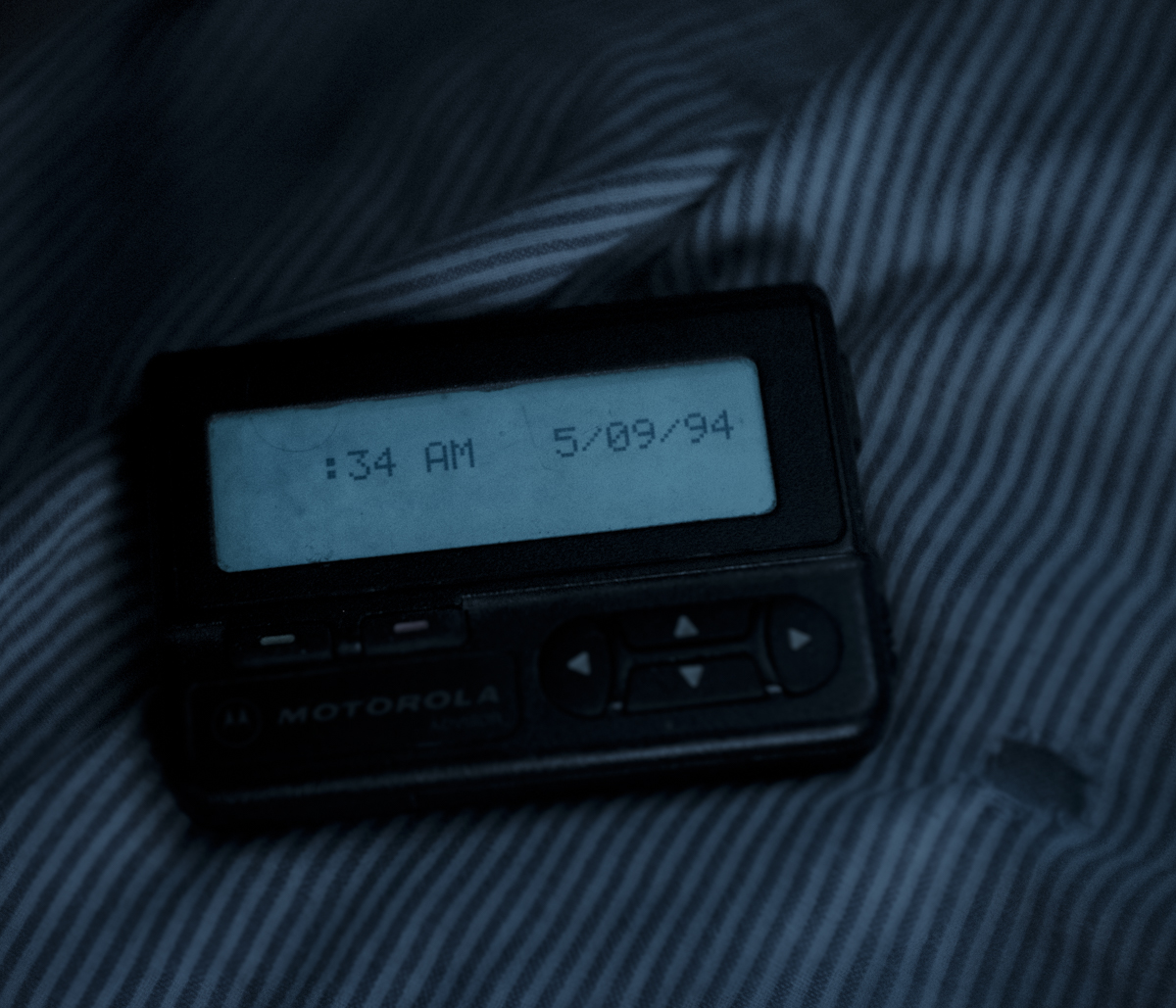

Since they were little they learned to be silent. It does not mean that “all” families in Colombia have a connection, it is not like that. But there is a good part of society that has had or had to naturalize that. There are children who, in the end, saw it as natural that there were weapons in the house and strange things would happen. What I did was get close to people to collect these stories and try to photograph around them. Along with the stories I began to make an archeology of the objects. I started by photographing a beeper from the nineties. He had belonged to a narco, he was part of a mockingly self-styled group, such as ASOTRAPO, Asociación de Traquetos Pobres, a group of traquetos from the south west of the country who were never great drug traffickers or managed to amass more than problems, fighting to get something from the cake and survive the winding path of shady businesses. Later, on the labyrinthine road, a jacket appeared that belonged to one of the Ochoa brothers, who were part of the Medellín Cartel; then video games, a G. I Joe toy that a drug lord gave to a friend, some jewelry. The inventory is growing, but it is increasingly difficult to photograph them.

And if for half an hour we have not uttered the phrase “drug policy”, it is because we are finally talking about the daily life of a lot of cities, their tensions and economic, affective, emotional, subsistence and symbolic flows. And this cannot be reduced to if we block a chemical with which an alkaloid is produced, or to kill the crops with aerial sprays of glyphosate.