The Long Decisive Moment when a World is Put to Death

On one of his trips, the Brazilian photographer Pedro David received a message that meant much more than news: Henri Cartier-Bresson had died. Together with João Castilho and Pedro Motta they were working on the Paisagem submersa project, an initiatory work that made them known. With the death of the teacher, Pedro David understood, the type of photography he had made was ending.

Paisagem submersa was a school for Pedro David. The ‘decisive moments’ in his work are not of seconds, they are of years. His images have several layers of reading and meaning. The construction of each photograph he creates is slow, thoughtful, meditative.

For him, it can be believed that there is a certain mysticism in thinking that when an image is created, everything that happens to make it count and adds up to the final result. But he firmly says that he is not a mystic man, he knows that there is a technical process and that, nevertheless, everything that goes into that creation is important. The time, the moment, the place, the relationship that he establishes with the different elements, the sensations, the sounds, the ways in which the light enters his camera, the formats and supports that he chooses.

Before moving to a rural area of Minas Gerais, Pedro David lived in Belo Horizonte for a long time and says that because it is such a young city, almost all of its inhabitants have roots in the interior of the state. He has gone in search of his roots, and has made photographs of the images that he has in his memory. He also takes photos of what he experiences on a daily basis, of what impacts his closest reality. “The motivation for my photos is in the news, in what happens in the world, but my images are not that,” he says.

Your work is strongly linked to nature, was it always like that?

The truth is I did not start with nature. My first published professional works were not about nature. In the 2000s I was delighted with the relationship between people and their environment, not just the natural environment. Two of my most important projects that were published and which are my professional initiation projects had to do with people in their places, in those cases both were made in the environment of the interior of Brazil, in the area that we call sertão: the interior, the limit of urbanization, the limit of civilization. I spent several years working on that. Nature appears because people are there, sometimes in a rural area, other times in a suburban area. That was a particular moment in the history of Brazil. Lula had come to power and was taking the idea of development to the interior of the country. It seems to me that this affected the photography I took at that time.

In Brazil there is this myth of the sertão and that has to do with an internal border and its expansion. In the year 2000, which is when I started to work, a new front appeared, an intensification of the idea of expanding that frontier and that is what I found. These are typical changes of that moment. The largest project was Paisagem submersa, which was a collective effort. In photography workshops at the university I met João Castilho and Pedro Motta, and we started working together. For us it was a very important job, it was also well known here in Brazil and abroad as well.

The project arose out of an interest to go inland, we had identified that it was not a topic so explored in Brazil. We found the Jequitinhonha valley, a region that was being part of the extension of the internal border of Brazil, an important region in the culture of Minas Gerais, very humble. In that region we found that an old project to build a hydroelectric plant was being resumed, to do so they were going to expropriate many lands to create a lake and many communities were going to be displaced.

For us, doing that job was the possibility of talking about that root of Minas Gerais but also about ourselves. Everything I’ve done since is tied to that story. We decided instead of bringing something that was far away to Minas, to bring a little of ours, of which we would have more property to talk about. So we began to photograph that region and tell about the lives of the people in that expropriation process. We ended up doing a very subjective and not very descriptive job, as we worked with people’s ideas and imaginations and not with the fact of the flood. We did a photobook and a series of exhibitions. For the three of us, that project was a school and it was the way to put ourselves on the scene.

But it wasn’t quick, we made a lot of trips in five years. They were short trips, in 500 km we were already in the region. That was important because we just wanted to be able to go back and be deep. And it was so profound that we began to do other projects, each one on his own. Paisagem Submersa was a collective project but the collective ended with it.

During those trips I discovered myself as a photographer and became a professional. I could remember that my parents had worked in the region a long time ago. So, during those trips I began to develop Rota Raíz, another work that is also very important to me, which addresses subjectivity even more. It doesn’t have a concrete fact. There my interest was to make my own image of those stories that were in my head since childhood. I started to interpret, I have never create total images, they were more subjective interpretations. That work has a documentary part related to what I was seeing: a region of Brazil that was going through an intense change.

At the end of that process, more or less between 2008 and 2009 I did another job in the interior of Pernambuco with a government creation grant. Tracing the northeast was a dream that also has to do with a very important character in the history of Brazil: Lampião. He was a bandit who was part of the Cangaços during the 30s, they were very complex, controversial and poorly explored characters in the history of Brazil. Lampião was a great bandit, a criminal who left society, created a gang and spent 20 years going around the sertão, without being caught by the police, all that ended when the roads began to be built. When that technology arrives, a point is reached where they can no longer hide. Also, when I studied we used a route map with travel guides.

In the Pernambuco region there were notices on the map that warned that it was a very dangerous region of robberies and assaults. With that in mind I made a series called Homem pedra, wondering if I could really travel to that region, which had portraits contextualized in nature.

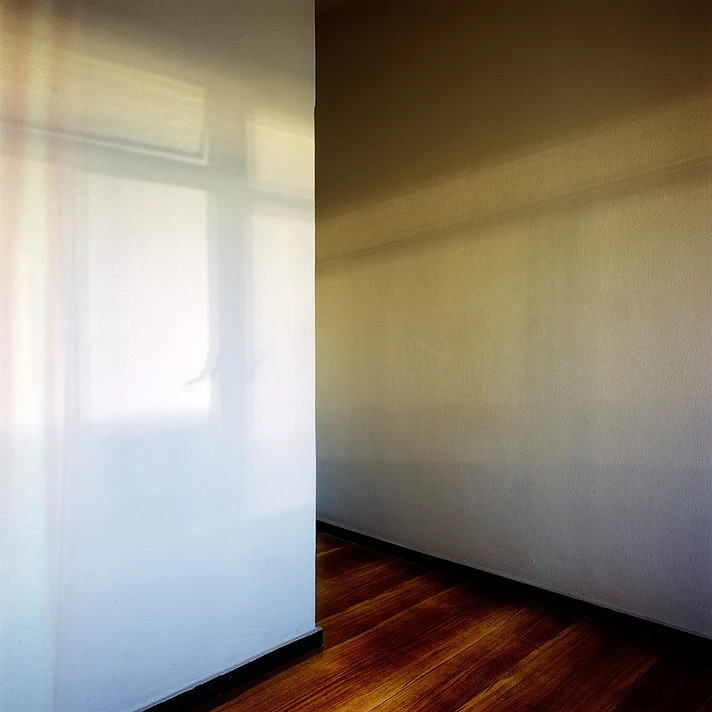

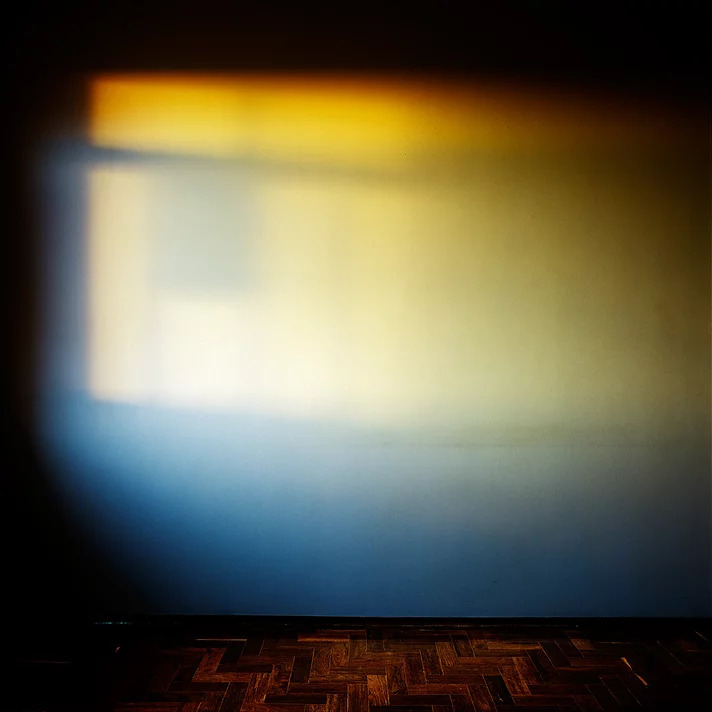

But after those works my procedure changed and the portraits disappeared. The human figure no longer appears in my work. I devoted myself to more urban themes. For a personal matter, I had to move and then I began to photograph empty apartments. At that time the real estate crisis in the United States occurred and that had an impact on Brazil. To find apartments to rent was very difficult, people began to sell their houses for fear of devaluation. Later I moved to the outskirts of the city, to Belo Horizonte, and began to take photographs of what was happening there, of the expansion of the city. Now that neighborhood is highly valued because everyone wants to go to live in the suburbs, but at that time it was not something so obvious, that expansion was just taking place.

Later, on a trip to do a work on Guimarães Rosa, I came across a scene that greatly changed my situation. It was a eucalyptus field like the ones I had already photographed, but I found native trees within the eucalyptus field, which is very rare because when the company gets a license to plant eucalyptus, the license allows them to dismantle everything. However, at some point in a region a law was enacted that allowed deforestation with the condition of preserving some species that were there. I felt inside a desert in the middle of the eucalyptus trees; but I was able to photograph a bit of the cerrado, of the native within capitalism. The Cerrado is the second largest biome in Brazil, it is a savannah that is being totally threatened.

I understood that scene as a decisive moment. I knew that that tree was going to disappear, it was going to be cut down, but it was there at that moment. In the future the Cerrado will have only eucalyptus trees. Before, all plants were native. And right now there are native trees within eucalyptus crops. I decided that I needed to photograph that as a defining moment à la Cartier-Bresson, something that is happening at the very moment it is recorded. Only this is not a moment of seconds, it is a moment of 7 years.

I decided to call it Madeira de Lei because that’s how protected wood is called. Today, if you buy a piece of furniture made of real wood, it is very expensive and rare, because that type of wood is increasingly scarce. Each image received the title Sufocamento. I felt suffocated there in the middle of the eucalyptus trees. They are rare trees, very monotonous, they dry the earth and grow very fast. For me that is not nature. When you go out into the field outside of the crop you can see many animals, none of them live inside. I walked those fields a lot, and there is a particular noise of the leaves and branches that one steps on, that noise began to suffocate me, it made me nauseous. It’s a desert.

And all that is going to be the future. The Cerrado will disappear. Currently, this is the region most affected thanks to deforestation to expand the agricultural and livestock frontier. This biome is not valued, and is very important, a large part of the water sources in Brazil exist thanks to the Cerrado. From that, I decided to continue working on this area and when I moved to the countryside, I started another series in which I want to show the intact Cerrado: boxes full of plants, only plants. I want to bring that to homes in urban environments, that vestige that remains and that I think is going to end soon.

Something that stands out in these photos, particularly in the Madeira de lei series, is the feeling of invasion. That also refers to what you were talking about the expansion of agricultural, urban or civilizing borders?

It’s the new landscape. The worst thing is that there is more and more of that, it is easy to get licenses and, incredible as it may seem, it is legal. These companies do everything legally and, in fact, they are defended by the population that lives around and that is running out of water, the neighboring population that receives all the poison that falls when the planes fumigate. The old owners also cut down and plant eucalyptus because that sells, it is safe money. When they sow, they know when and how much they will earn. These trees are turned into charcoal for the steel mill’s furnaces, which when mixed with iron produce stainless steel, the country’s most important export product.

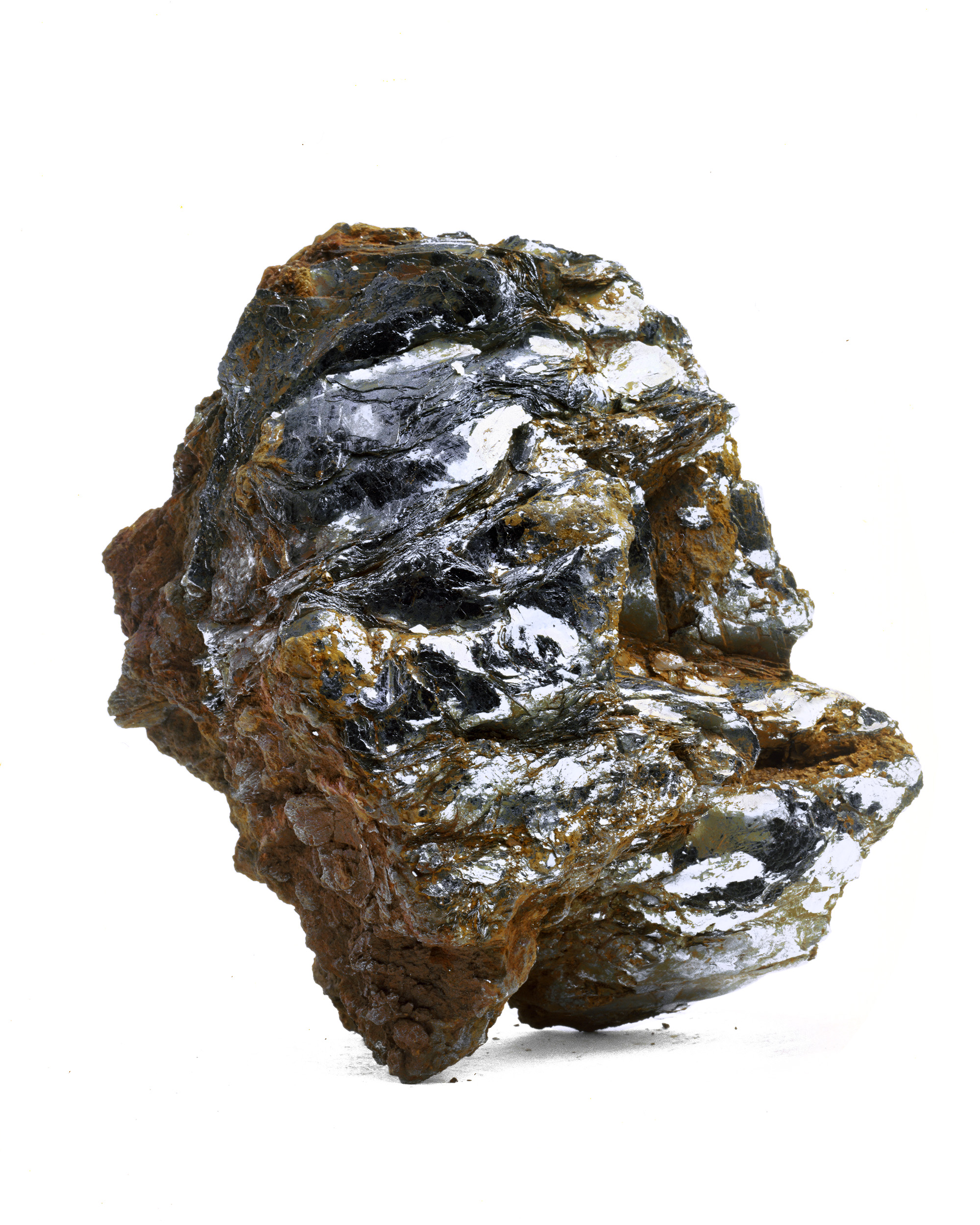

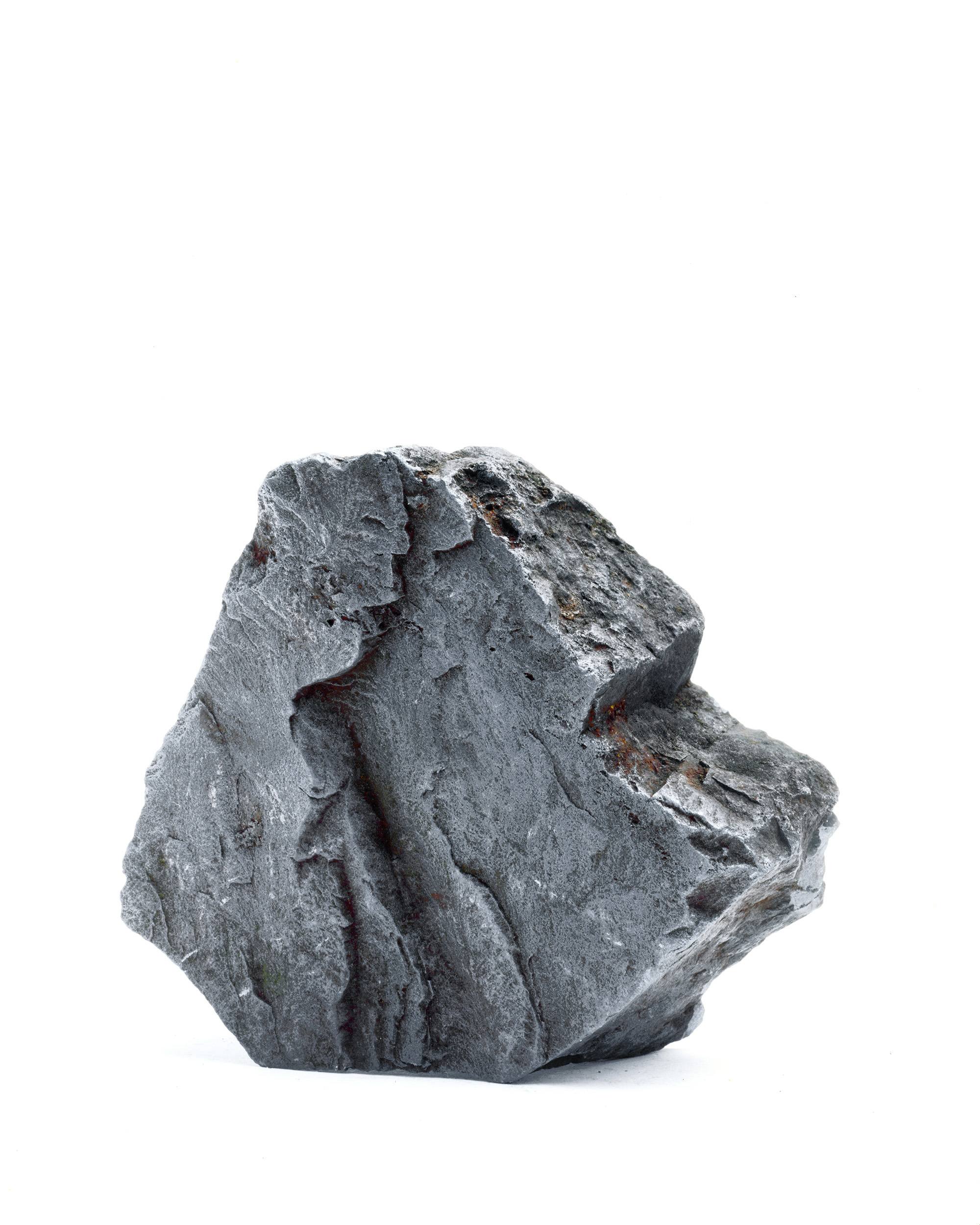

In another series that I developed about 100 kilometers from here, in Nova Lima, in the area known as the Iron Quadrangle, the region where there is the highest concentration of iron in the world. There are at least 7 very large mines near that neighborhood. In 2015 I started a series called Terra vermelha. I noticed that when the neighbors removed the earth to build their houses you could see that mineral material. I took photographs of the earthen walls to raise a reflection on that material. It is something that is in people’s houses, in the mines they make the same movement that my neighbors did to build their houses. The mine wants people to get out of there. The photos were not made in mines, but there were neighbors who decided to extract the mineral.

I wanted to make a image more pictorial than photographic, I didn’t want a portrait of the world, I wanted to make a gesture, a blow.

I like to play with images that do not say everything, we are used to documentary photography, to images say everything, but it is not necessary. I am interested in creating images that generate certain sensations when you read it, that bring a force that is not in a specific action but in the language of the image. I did that series at a time when I was very interested in American abstract expressionism. I wanted to make a image more pictorial than photographic, I didn’t want a portrait of the world, I wanted to make a gesture, a blow.

How do you think your photographs are interpreted in different contexts?

I think in different ways and that diversity interests me a lot. That is what Roland Barthes said, that when the author publishes, he dies and is less important, the work creates meanings where it arrives. I really like to know different readings, but I like it more when a person from a very different culture has a reading similar to mine.

I’m really happy when that happens. Once I showed my series Aluga-se to a Russian editor, and she knew what the word that accompanies each photo meant, and it is the name of the street where the apartment was located where I made the photo. In telling her how I did that job, she told me that she was going through the same thing in Leningrad. That showed me that it was not just a personal thing, it had a documentary question of interpretation of the time.

In the case of eucalyptus trees, I really like it when people get out of the factual issue of the nature of the Cerrado and see it from a totally subjective and conceptual perspective and think of people in their homes, displaced people in cities.

That ‘decisive moment’ way of thinking is very interesting. Thinking a decisive moment of years and not seconds challenges classic and traditional ways of thinking about photography. Among other things because this idea of the decisive moment thought as Cartier-Bresson proposed it, also implies a myth in the creation forms.

It was another time. When we were developing that first project, Paisagem submersa, we were photographing a situation that had not yet happened. We knew that they were going to flood, that a lake was going to appear and that they were going to get everyone out of there. We were young and we wanted to see the water arrive, and we wanted to have the job done, in youthful anxiety. We didn’t want that to happen in four years, so the project had to happen. At the same time we discovered that the local people were also very anxious because their lives were going to change a lot in a permanent and radical way. They constantly asked us what we thought, if we knew something, if we thought they were going to flood…

The work was heading towards that side, you had to have that image of the water, it was not to wait and complete. We started in 2002, we had an exhibition in Holland in 2005 and we stopped photographing in 2007. The lake was full in 2007. We already had work because we were doing things, and all the time we were editing, preparing portfolios, in that process we talked a lot and we realized that in our work the ‘decisive moment’ was not enough, there was no that moment, we needed to build. We could not wait for a person to make a gesture that had to do with water, they didn’t want to either, and we understood that we were not hunters, that there was no longer that decisive moment by Cartier Bresson, there was no more waiting for the documentary.

There was also a funny episode that I always like to tell. I went on a trip in my car and received a message from João, one of my colleagues, saying: “Cartier-Bresson died.” He really died. Just when we thought we didn’t need that teacher anymore.

Another important thing to note is that he is one of the symbols of powerful Europe, of the ethnocentrism of the idea of: “I can travel the whole world, I am a man, I am rich. I show you this world to which you will never come ”. But we knew that this was no longer the case. We know that there are people in every place who can do much more powerful jobs than foreigners who are going to tell their realities.

In your work you mostly use analogous materials, and the importance you give to the materials of each piece is interesting. How is the choice of technique and materials based on the language and the work created?

That is something very important in my procedure. First of all, because when I started to do photography, there was still no digital model. When I started, the film was still used, the format was chosen, but not the type. I learned to work with film and acquired all the equipment to work like this. The digital was arriving and I also experimented, for my commercial work I bought a digital camera, but I did not want to leave the film. For me, learning to master the film was something enjoyable and very important. I decided to continue there, because I also saw very similar things in digital. In some of my works I have also experimented with digital, it allows me to see some things before, but I continue with the film.

I am also interested in generating a reflection on time. In Terra vermelha, I used a large camera that takes time to install. I wanted to stay there for a while in front of that material, in an almost performative way. It wasn’t taking the photo and leaving.

There is something about time in some of your series. The photos are taken at a specific moment, a present, but being right in moments of change allow us to see the past and be, at the same time, a window to the future.

Yes, perhaps particularly in Madeira de lei. In the next few, I’m not interested in doing that, unless I find a very good opportunity. But in general I am not interested in that photo that you see a lot in the press of the border between the jungle and the cultivated field.

In my new series on the Cerrado I try to show it untouched, I look for an angle in which it looks full, enormous. The reality is that the preserved area is small, it is surrounded by deforested places, but I am interested in generating a dialogue from that. Also, I am interested in that time that I spend there with those trees, which I dedicate to choosing the cutout that will be my photo. All of that counts. Perhaps you can speak of a mysticism, but I think that in the end it counts. My relationship with that space is going to add up. Even knowing that the production of the image is something technical, for me spending that time there adds to what I want to say about it.

I’m not interested in doing documentary photography, I’m much more intimate. I see that kind of photography and I value it, it inspires me and gives me ideas. My work is strongly linked to the news but not the photo, the motivation is.

Por: Marcela Vallejo