Following the Charrúa family tree

The Archive of Charrúa Memory is a multimedia platform that combines family photographs from individuals who self-identify as Charrúas. The Uruguayan Army decimated this ancient indigenous nation during the Republic’s early years, and its descendants have remained invisible ever since. The project by the Colectivo Nativo is one of the recent initiatives that seek to impact the debate on the current situation of this community through visual work.

By Alonso Almenara

We have all heard of the “Charrúa spirit” at some point: that typical expression that identifies the fierce style of Uruguayan soccer. “There lies a paradox,” observes photographer Federico Estol. “The phrase alludes to the rebelliousness of the Charrúa people, the indigenous people who couldn’t be conquered, who the state wouldn’t kill. Much of the Uruguayan identity is recognized in that strength. But at the same time, the state does not recognize the Charrúas as an indigenous people. So, they are present in the minds of Uruguayans, but surreptitiously: their attributes culturally transferred to the soccer field.”

That is partly a consequence of the scarce record we have of the customs of the Charrúa people before the arrival of Europeans. We know they were nomadic gatherers and hunters, and their physical features are still present in many Uruguayans. “But since they were nomadic, there are hardly any material remnants of their culture. This makes it very easy to deny their existence, as indeed happens in certain academic circles,” comments Estol.

Although Uruguay is one of the most progressive nations in Latin America in terms of social policies, its state apparatus has thus far been unable to acknowledge the genocide of the Charrúa people that occurred in 1831 at the hands of the Uruguayan Army, let alone address the situation of invisibility in which individuals who self-identify as Charrúas find themselves today.

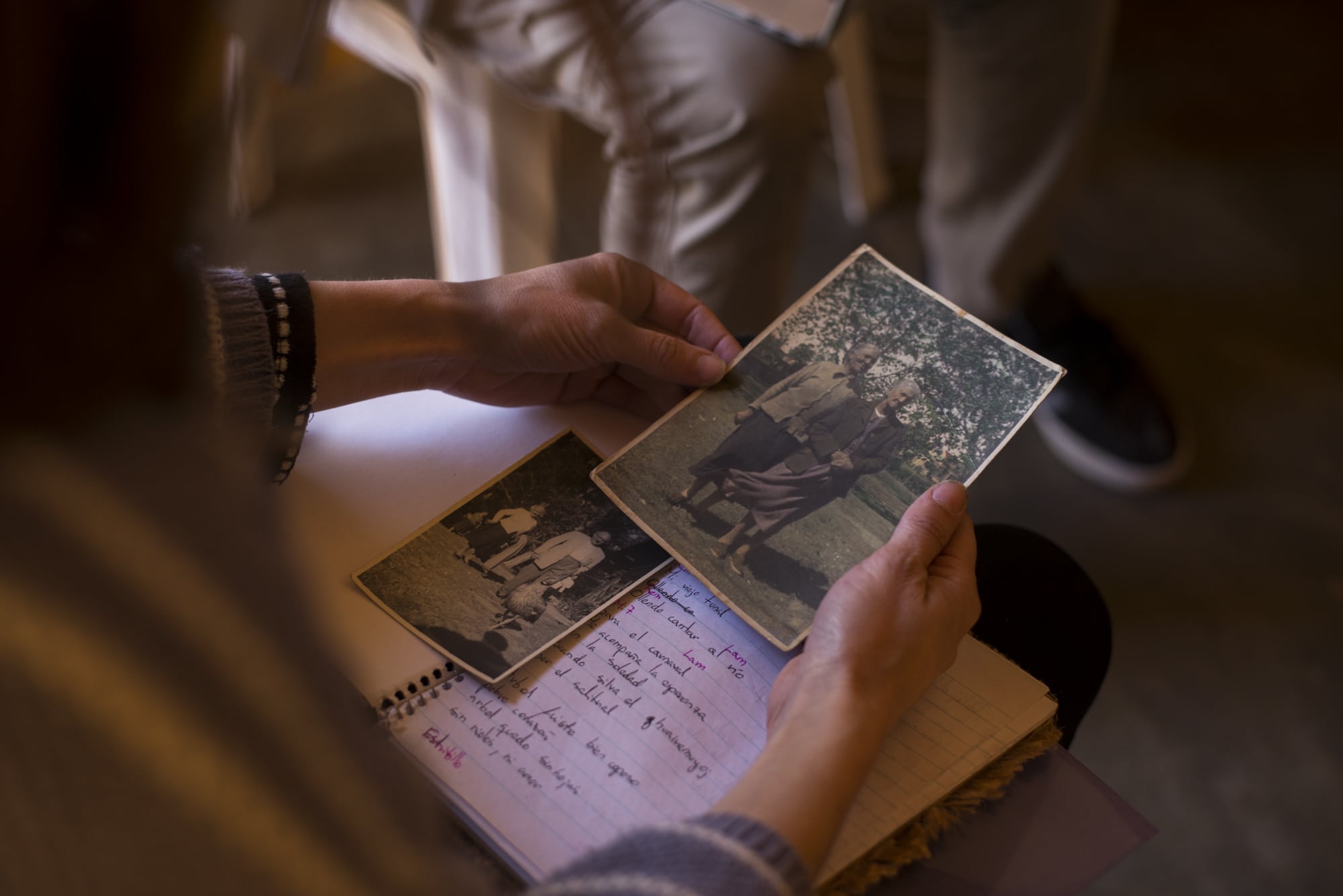

However, there has been a growing mobilization of indigenous organizations fighting for recognition in recent decades. Initiatives have also emerged in the field of visual work in response to this issue. Estol is a member of Colectivo Nativo, which he co-founded in 2015 alongside photographers Lorena Larriestra, Diego Alegre, and Nicolás Vidal. Two years ago, they created the Archivo de la Memoria Charrúa. This web platform compiles an inventory of nearly three hundred family photographs contributed by individuals who self-recognize as Charrúas and public-private institutions.

We spoke with Federico Estol and Nicolás Vidal about what the rescue of these archives can offer to the current debate in Uruguayan society within the context of an identity resurgence driven by indigenous organizations themselves and an ongoing global discussion on the unrecognized rights of indigenous peoples.

“We don’t engage in academic debates about who the Charrúas are; we focus on people who feel and identify as such. Some people are white, blond, blue-eyed, and have a Charrúa grandmother on their maternal side. We want photography to be a vehicle for making these family memories visible.”

How did this initiative come about?

Federico Estol: The project was born out of the need to work on something that has not been extensively explored in our culture: the indigenous peoples and their oral memory. There are, of course, research studies in the field of anthropology, as well as studies of archaeological remains such as “Los Cerritos de Indios.” But that’s all that is discussed and taught in schools: material remains of the past. There is no discussion about what is alive. And this can be explained by the history of Uruguay itself, a country that was born through the genocide of the Charrúa people, which took place in 1831.

Fructuoso Rivera, the first Uruguayan president, was in charge of what was understood at the time as “pacification.” It’s similar to what happened in Argentina and Latin American countries. But in Uruguay, the extermination campaign was very rapid and effective. The climax was the Salsipuedes Massacre, an ambush that occurred on the shores of the Arroyo Salsipuedes Grande. Fructuoso Rivera had offered a truce to the Charrúas living in the area: he offered them meat and liquor and attacked them with a hidden battalion. That’s how the Uruguayan Army was born: its first planned task was killing indigenous people.

We had been working on other projects as a collective, but we had always been interested in this topic. We were also familiar with the work of other photographers on the continent, focusing on living indigenous peoples. We knew about the communities here, and we had heard about organizations like the Charrúa Nation Council. And these people are alive, resist, and preserve their rituals and customs. They have been organizing since the 1980s, after the fall of the dictatorship. It’s not an integrated community but rather scattered groups that cultivate their rituals and safeguard their oral tradition.

One of the obstacles they face is that the situation is complicated within academia. There are still disputes about whether the Charrúa people truly existed, had their own cultural characteristics, or were just an amalgamation of different indigenous tribes. It is also unknown how many of them there were. And there is no official consensus on whether what happened in Salsipuedes was a genocide or not. As a result, there has historically been little awareness of this indigenous legacy in Uruguay. But this started to change with the 2011 census when ethnic self-identification was included for the first time. In 2015, when we founded the collective, 5% of the population self-identified as belonging to indigenous people. That was a crucial piece of information.

Has this topic been explored before in photography?

Federico: Regarding visual work, it’s almost uncharted territory: there was everything to be done. As photographers, our focus is on working with the community. It’s always photography connected to people. And we felt it was essential to start creating an archive that brings together materials scattered in different family archives. Our initial mission was that when you searched “Charrúas in Uruguay” on a web search engine, you wouldn’t only find old engravings made by Europeans and the

What was your working method?

Federico: Initially, we wanted to represent some typical scenes of Charrúa’s life, which was a mistake. The indigenous groups themselves told us they didn’t want us to folklorize them. It wasn’t necessary to recreate them, to envelop them in a fictitious life. From that reflection, the idea emerged to collect the memory of family photos preserved by the people and historical museums. Institutions that, by the way, do nothing with all that information. The state has a double discourse: denying the Charrúa people, but they give you the photos if you consult the museum.

We don’t engage in academic debates about who the Charrúas are; we focus on people who feel and identify as such. Some people are white, blond, blue-eyed, and have a Charrúa grandmother on their maternal side. We want photography to be a vehicle for making these family memories visible.

Nicolás Vidal: One of the archives we worked with is from the National Historical Museum, which is Fructuoso Rivera’s house. It’s an incredible situation: the museum bears Rivera’s name, the president who killed them. And at the entrance, there’s a statue of a Charrúa. There are many contradictions of that kind in Uruguay: there’s Parque Rivera, with the Charrúa Stadium inside. The leaders of indigenous organizations told us that they are not descendants; they are Charrúas. We had to think about changing the discourse and how we were conveying it.

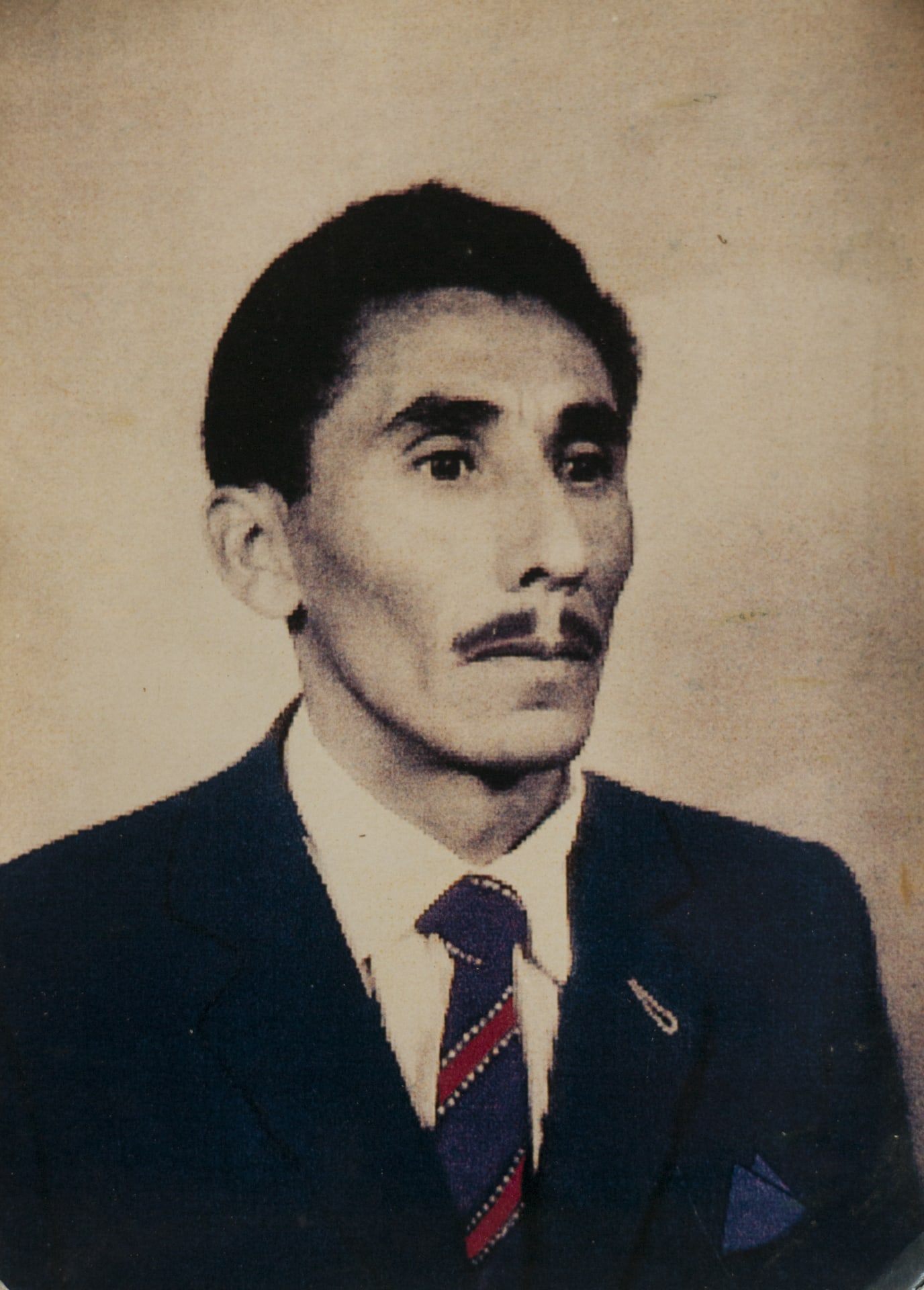

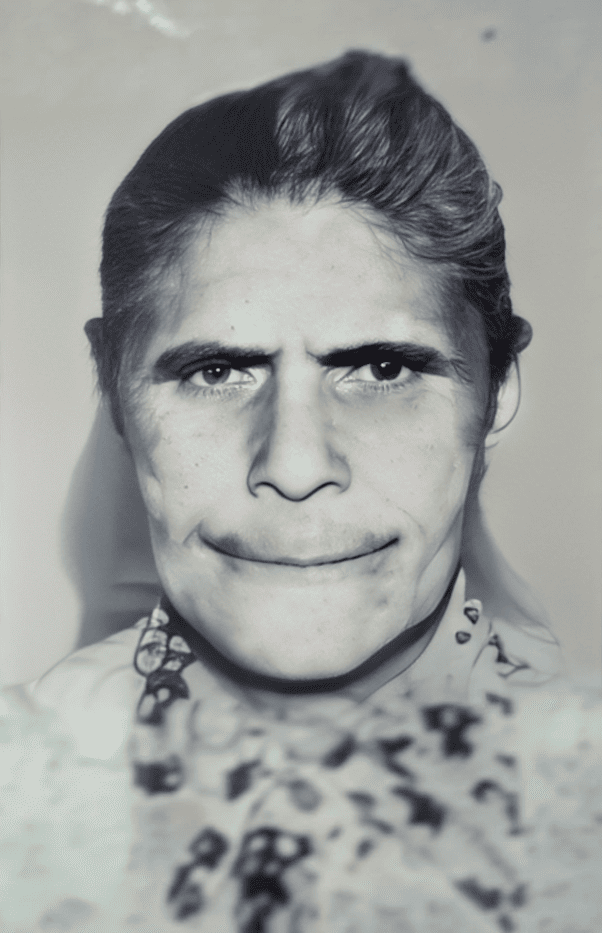

Regarding what Fede mentioned about the portraits we made at the beginning, it’s true that we felt we weren’t getting to the heart of the matter. Still, that experience led us to notice certain common features: the shovel-shaped teeth, the slanted eyes, and the tall physical build. When we went to Tacuarembó, we had a situation where the person attending us at the museum, who had all the features of being Charrúa, had no idea about it. That happened many times. And it happened to me too. You start to wonder where you come from. In Uruguay, we have this logic that we are all children of migrants, children of Spaniards or Italians. It’s what they sold us our whole lives. But through research by anthropologist Mónica Sanz, who traces Charrúa’s genetic heritage through fingerprints, I discovered, by referring to my mother’s ID card from many years ago, that she also has Charrúa ancestry.

Fede already told me about the features. I asked my mom about my grandmother, where she was born, and she didn’t want to tell me. Finally, she said her mother was adopted. It’s something that repeats within the Charrúa community. After the Salsipuedes massacre, the army started selling or giving away the survivors to disperse the families. Some were taken to France, like Sepé, the last Charrúa chief, who was sent to a circus and ended up dying there.

Federico: We had the experience of going to different towns where we ended up awakening the same curiosity in people: who were their ancestors? There are a thousand indications: the Mongolian spot on the back, even the negative Rh blood characteristic of the indigenous population in northern Uruguay. There are also persistent Charrúa customs, such as the moon bath, which is done with newborns during the first full moon, or the Indian horse taming. The denial of Charrúa’s identity also came from community members because they had to do it to integrate into society. They changed their surnames to avoid discrimination, to continue having jobs, and survive.

Nicolás: We receive inquiries through the website and our Instagram account asking about certain things if we have contact with a particular family. That question of where we come from and who we are is in the air. The idea that we are children of Spaniards or Italians doesn’t hold up. What is lacking is information. The topic of Charrúas is superficially discussed in schools. There has been significant work by researchers in recent years, but the prominent historians who are in the media seem oblivious to this concern. For them, nothing happened. There was no genocide, it was pacification, and they present the Charrúas as criminals, people who stole everything, stole cows, and killed people. That’s why it’s essential to think about who tells the stories and from what perspective they approach them.

Do you perceive an evolution in Uruguay’s public awareness level regarding the Charrúa population?

Federico: The past few years have been important for the Charrúa community. Something interesting that has happened since 2015 is that indigenous organizations, which the state had entirely hidden before, have digitized and incorporated new tools for organizing. They even have parliamentary advisors now, and there is an indigenous representative in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. In visual documentation, our project is not the only one that has emerged around this topic. I think, for example, of the exhibition “Visibles” by Rosana Greciet and Ignacio Seimanas, which consists of a series of portraits of members of the Charrúa community, and the documentary “Un país sin indios” by Nicolás Soto and Leonardo Rodríguez.

We chose to investigate family memory, and the truth is that we have found precious material. The oral accounts we have gathered are also powerful: they tell, for example, how these people had to hide, how they had to change their surnames. We believe it is now possible to reconstruct the Charrúa people’s family tree. That would be the next step in our project.

The website also includes academic research recommended by the indigenous organizations themselves. These documents, in my opinion, should be in every school. And we would like to do more with that: animations, videos to integrate into the archive. We want this to be a reference tool for education and the indigenous communities.