The footprints of my mother have not been erased

Cindy Muñoz Sánchez was awarded at the latest POY Latam with her project “Altars for Estela” in the category of “Resignifying the Archive.” The series is part of “Es-tela mi madre,” a long-term project that started as an idea in 2009 and began to materialize in 2014 with a collage she made with her daughter. The project has a performative and a photographic aspect: both document and elaborate on the search for her mother, the process of resignifying loss, and the construction of a political perspective that now permeates all her work.

By Marcela Vallejo

The last time Cindy Muñoz Sánchez, a Colombian photographer and artist, saw her mom was when she was about six years old. She lived in Cali, in the southwest of Colombia, and her mom lived in the Llanos Orientales(Eastern Plains), probably in Yopal. There are no significant certainties, but that’s what the traces she has found throughout her life indicate.

Cindy was born in Cali. When she turned eight months old, Estela, her mom, decided to leave the city, abandon her home, and take the little girl. They arrived together in Bogotá and shortly after continued towards the Llanos Orientales. What happened there is unknown, but they traveled through several cities and towns between Villavicencio and San José del Guaviare.

Following a hunch, Cindy’s dad arrived in Granada, in the Meta region, and found her. She was already four years old. Not much time passed, and he decided to take her to Cali and separate her from Estela. From that point on, Estela’s story becomes blurry. Cindy knows that Estela visited her twice. Not long after the last visit, they learned that Estela had died, probably in Yopal, in the heart of the Llanos.

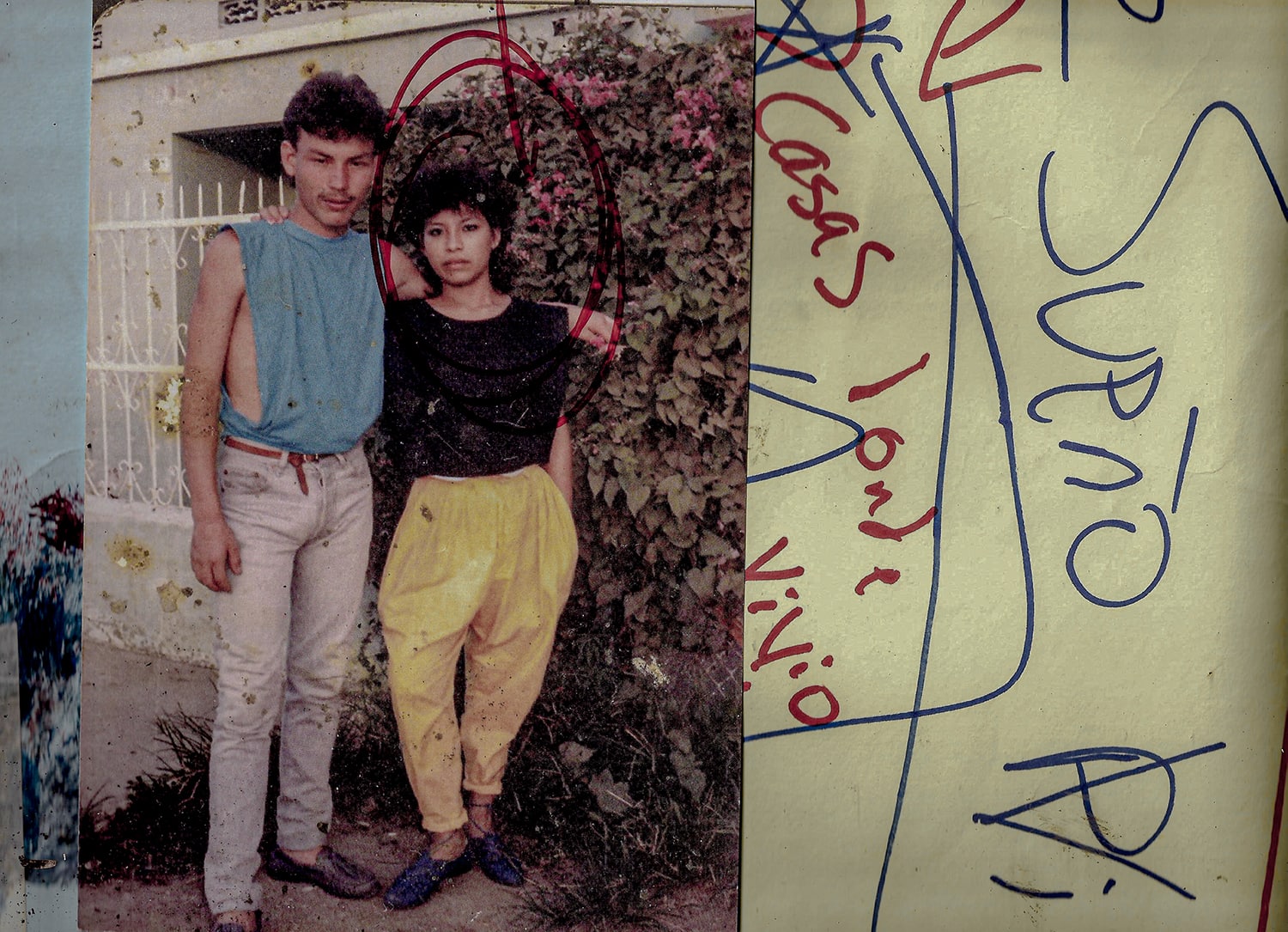

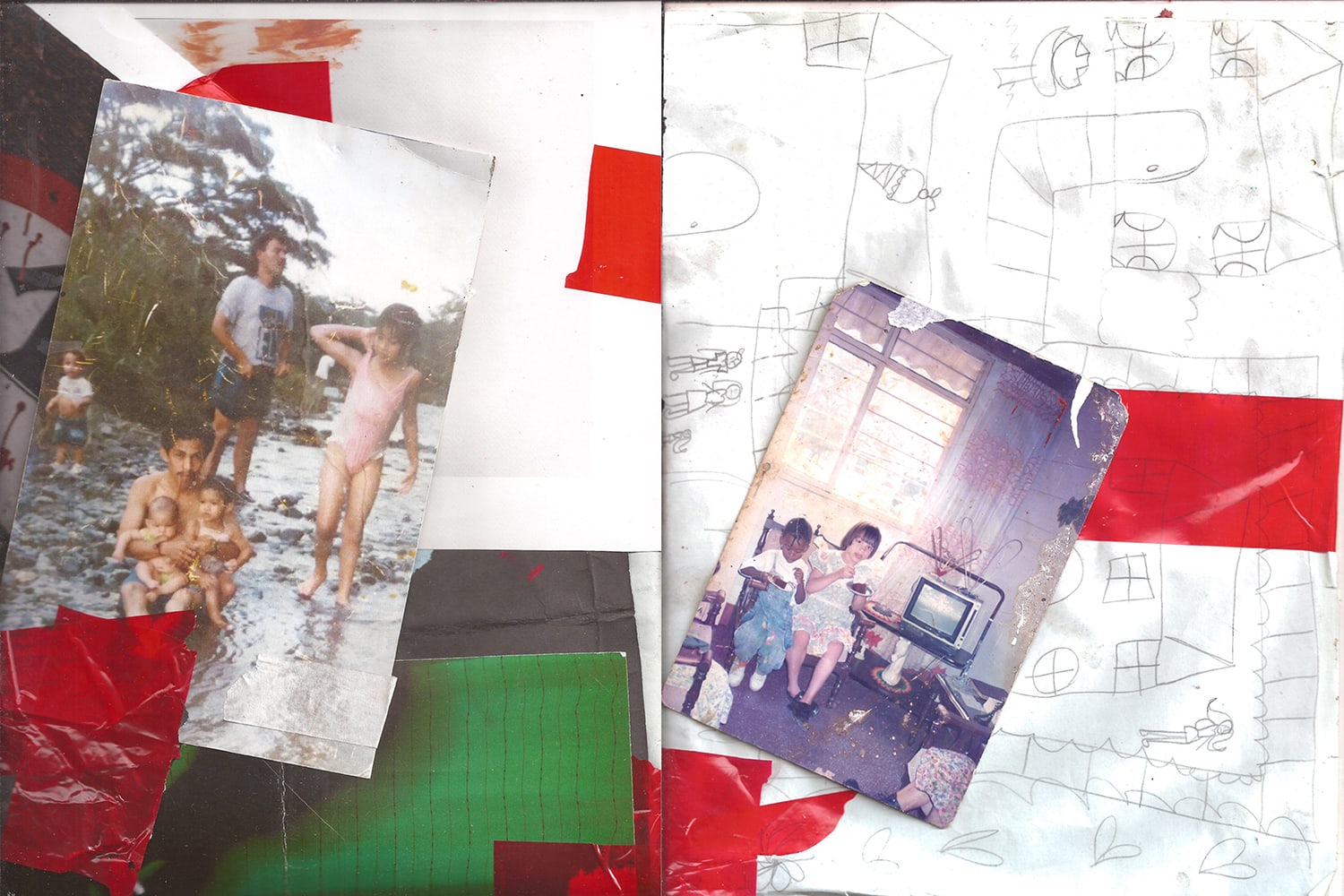

The artist recognizes herself as indigenous; from a young age, she knew she was different from Cali’s other boys and girls. Now she knows she is a racialized woman, just like her mom. In 2009, she began searching for her. She only had a photo of a young couple: she wore yellow pants, a black shirt, blue shoes, and permed hair in the style of the late ’80s. Next to her was a young white man with light hair, a thin mustache, and a light blue shirt. Behind them, you could see the facade of a house, a gate, and a plant with flowers. Over the years, Cindy found another image of a family outing, and with those memories, she gradually reconstructed the story.

Estela was less than 30 years old when she passed away. She had no identification documents, and her death was not registered. It is said that her mother was indigenous and lived between the Llanos and the Amazon. It is also said that her mother’s mother was indigenous and was born in Brazil. It is unknown which indigenous community they belonged to, whether they spoke a language other than Spanish or Portuguese. The reason for their migration is also unknown.

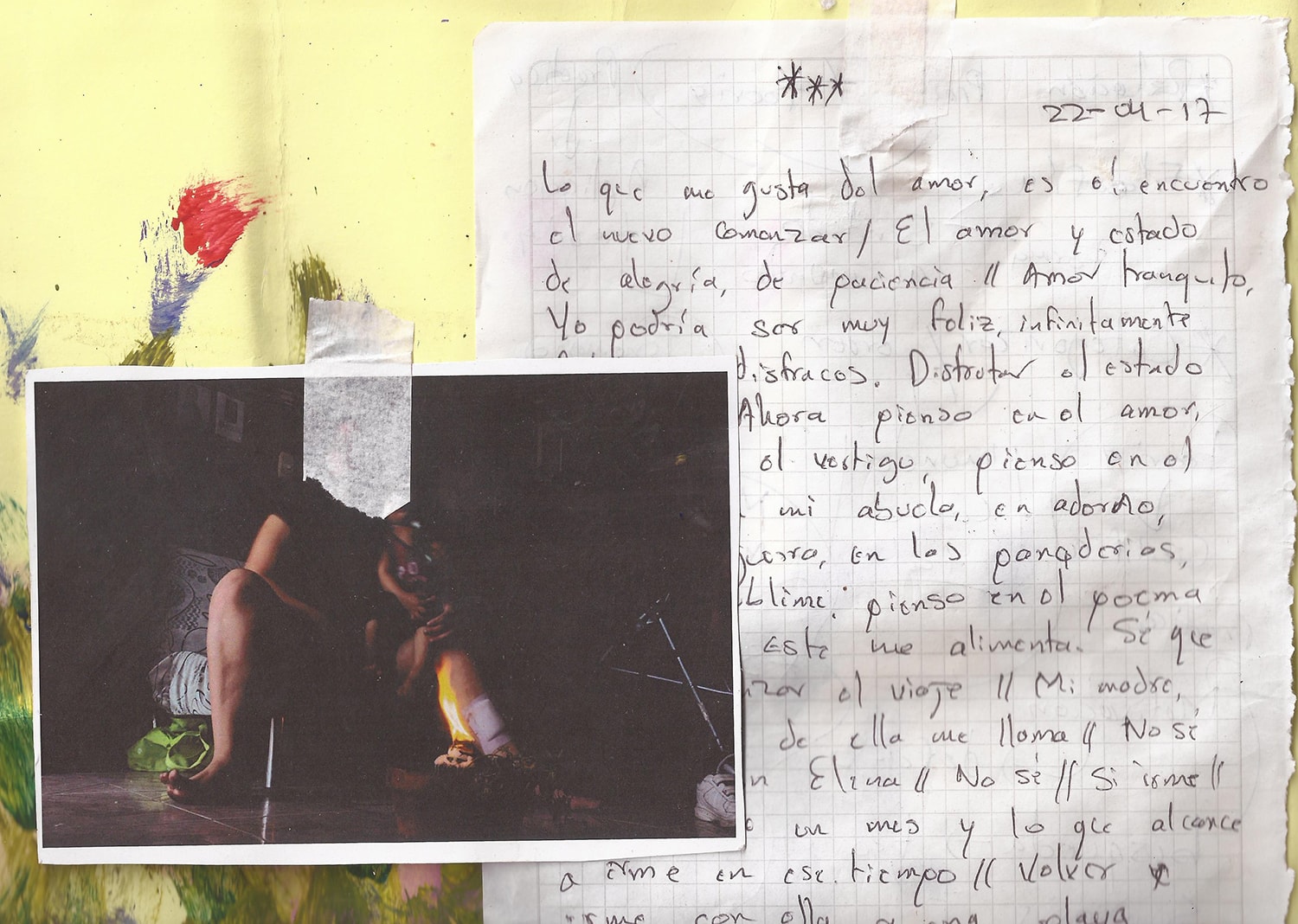

The lack of certainty and absence marked Cindy’s search. In 2014, she initiated a project called “Es-tela mi madre.” She refers to it as a macro project because it encompasses two lines of work: performative and photographic. The first line includes the essay “Altares para Estela,” which was awarded in the latest edition of POY Latam in the category of “Recontextualizing the archives.”

“The genesis of the whole project is to inhabit the places that my mother traveled in life,” the artist explains. “It’s the little I have of her, of her personal history. There’s a significant absence of both photographic and documentary archives. That search to tell her story, our story, much more difficult.”

In that search and constant confrontation with absence, Cindy decided to travel to the places where her mother had been. “Villavicencio, where she spent her childhood. Yopal, where she supposedly died. She lived her adolescence and part of adulthood in Bogotá. We lived together in that city and later in Granada, Meta. I’m not sure if we were there the whole time. Then it’s likely that she was moving through different places, including San José del Guaviare.” Estela went to that last city in search of her mother. “It’s possible,” Cindy affirms, “that my grandmother is still alive.”

Cindy arrived in Yopal in 2016, searching for her mother’s grave but didn’t find it. She also didn’t find any records among the missing persons. None of them matched her mother’s name.

The following year, she went to Villavicencio, where her mother spent part of her childhood. “One of the problems I encountered between Yopal and Villavicencio is that I didn’t know what to photograph. I left there with the idea that the project couldn’t be solely photographic or audiovisual anymore because I simply didn’t know what to do.”

Confronting that blockage led her to explore other possibilities. For Cindy, the territory pointed her in the right direction, and that’s how the performative and visual line began. She started a series of installations and performances called “Estela en Tránsito” (Estela in transit). This work is currently exhibited at the Banco de la República in Bucaramanga, in the north of the country, and includes video performance, installation, and live performance.

She wanted to revisit photography, and after those trips, she explored. For example, she played with the repetition of an image she had. But she couldn’t take photos, and during 2014 and 2019, she made a “political” decision not to use the camera. In that year, Mateo, her second child, was born, and for the first time, she took a self-portrait. That’s when she resumed the search with the camera in hand.

Two years later, in 2021, Cindy traveled to Granada with her son. “Before boarding the plane, my dad told me, ‘Now that you’re going there, and if you’re going to do it, you need to know that your mom was a sex worker, and if you want to know anything about her, you’ll find it in the red-light district.'” Cindy’s dad was embarrassed to say that. “He thought she worked as a sex worker because she didn’t know any other trade. In other words, being indigenous, if she couldn’t work as a cleaner, she had to be a sex worker.”

Learning that changed her entire perspective. Until that moment, Cindy saw indigeneity from a “very Western construction of the world.” “Realizing that my mom had been a sex worker made me think about what an indigenous body can mean politically, to understand that there are many ways of being indigenous.”

That revelation helped her better understand what it means to be a racialized woman. It also sheds light on some of her experiences, where others had assigned specific roles based on their perception of her body. This also led her to interview sex workers in Granada and San José. She showed them the photos, and some believed they recognized Estela. They saw things in the pictures that Cindy had never seen. Through them, she also learned part of the history and reality of that border region between the Orinoco and the Amazon.

The territory showed her that it wasn’t just about traversing the places her mother had been. She realized it was time to say goodbye and heal her wound, and that’s when she started the Altars. For now, they are photographs, but later they will become performative actions in the territories, especially the rivers.

Walking through the places and talking to people, she learned that multiple forms of violence had marked the region. She visited some indigenous communities and spoke with the elders. She discovered that the rivers, jungles, and plains had witnessed great atrocities. And she understood that her work, her story, and her mother’s story went beyond self-reference.

Estela’s story is likely that of many other indigenous, racialized women. It is the story of a woman who is non-existent in official records, whose origin destined her to certain occupations and not others. But it is also the story of a woman who made decisions about her own body and chose to live a domestic life—a woman who knew when to leave her daughter to secure her future.

“Speaking about grief and pain is very difficult. That’s why an internal immersion is necessary,” Cindy asserts—for her, all these years working on the project helped her move beyond the pain and overcome a death drive that haunted her for several years. The constant work of searching and processing allowed her to develop political tools and find her voice. She now knows that other women share her mother’s story, and it is unfair that “indigenous girls and women cannot live in their territories because there is a conflict that specifically targets us.”

The project has also given her strength to fight against the forces that aim to erase and disappear racialized bodies. “This has given me the strength to say that we deserve to exist, that we deserve, if we want, to be mothers, to have a good life and fight for it.”