Graphic art spreads like ivy

Exhibited at the MUAC in Mexico City after being presented at the Reina Sofia Museum in Madrid, the show El giro gráfico: Como en el Muro la Hiedra brings together close to 400 works that include actions, embroideries, banners, projections, intervened signage, T-shirts and posters. Results from the Red de Conceptualismos del Sur research team have marked the course of Latin American art, confronting urgent contexts and articulating strategies of resistance and transformation. We talked to Guillermina Mongan, one of the project coordinators.

By Alonso Almenara

No museum in the world has gone so quickly from being a dubious investment to becoming a reference for avant-garde museography as the Reina Sofia in Madrid. And this is due, in part, to the institution’s unique connection with Latin America. Manuel Borja-Villel, the museum’s director, recently described the continent as a place of “extraordinary experimentation,” which produced an art where “the collective mattered more than the individual” and where “popular culture mixed with the avant-garde.”

The Red de Conceptualismos del Sur put those ideas to work ten years ago in an exemplary exhibition like Perder la Forma Humana. Una Imagen Sísmica de los Años Ochenta en América Latina, done in collaboration with the Reina Sofia Museum. The curatorial proposal explored art forms on the margins of galleries and museum spaces, developing instead in the streets and responding to concrete contexts of repression in a continent ravaged by military dictatorships, economic crises, and armed conflicts.

What was striking was the vitality of the result: the countercultural pulse of art that responded to the savage repression of the State with punk, transvestism, and sexual liberation.

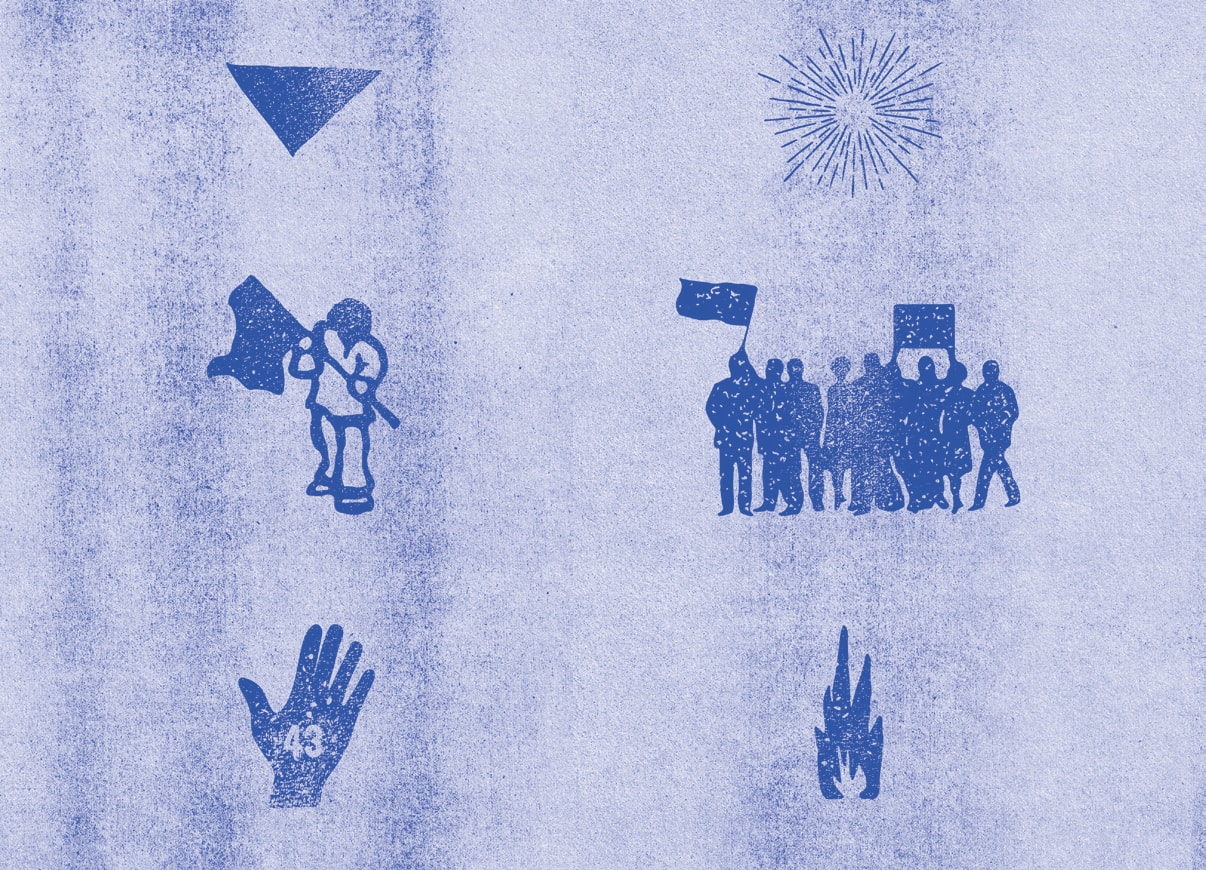

El Giro Gráfico: Como en el Muro la Hiedra continues that experience. The show was presented last year at the Reina Sofia Museum and is currently on display at the Museo Universitario de Arte Contemporáneo (MUAC) of the National Autonomous University of Mexico. Like Perder la Forma Humana, it explores the crossovers between art and politics in the continent. But it focuses on the present and the phenomenon of graphics understood openly.

“There are woodcuts, serigraphs, embroideries, woodcuts, woodcuts and even much more historical or artisanal forms of graphics,” explains Guillermina Mongan, co-curator of the show and one of the coordinators of the Red Conceptualismos del Sur (Southern Conceptualisms Network). She is an art historian, researcher, artist, and curator. After collaborating with Ana Longoni, one of the Red de Conceptualismos del Sur’s promoters in an exhibition on Argentine artist Oscar Masotta, she joined the collective. She has worked on El Giro Gráfico with 30 other researchers, including members of the Network and guests.

Perder la Forma Humana and El Giro Gráfico explore the crossovers between art and politics in Latin America. Still, they have different time frames: the former focuses on the 1980s, while the latter interrogates the present. What other differences and similarities are there between these proposals?

Although Perder la Forma Humana was anchored in the 1980s, it included some dimensions of the present, which connects it with El Giro Gráfico. However, the group of researchers has varied, which necessarily enriches or modifies the proposals since the research work in the Network is done collectively: everyone proposes their research in assemblies and plenary meetings where it is discussed.

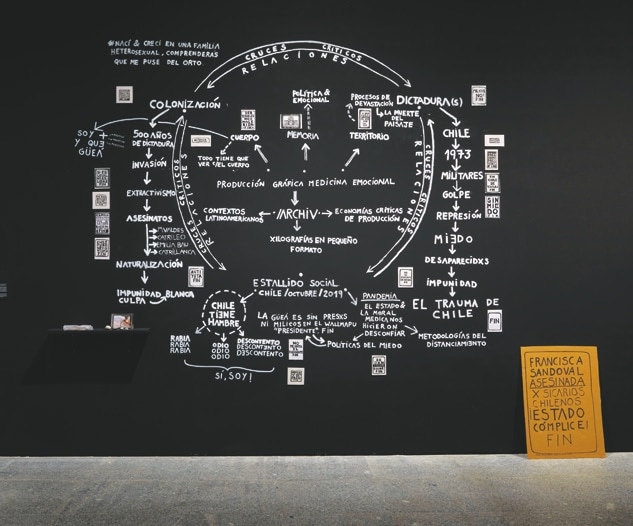

Another connection between El Giro Gráfico and Perder la Forma Humana is that both were worked in a diagrammatic, relational way. Still, the practice of incorporating the temporal dimension has changed. Perder la Forma Humana is thought more synchronic: it focuses on a specific decade, and although the cases are thematically linked, they are articulated from a timeline. El Giro Gráfico, while focused on the present, thinks of time in a non-linear way, as a spiral time, in which the future is not necessarily ahead, and the past is not necessarily behind. Let’s say that time twists, like Quetzalcoatl, the feathered serpent. I believe this spiral temporality is typical of the graphic arts, or at least it allows us to think about how some ways of doing things persist and others are being updated in the contemporary.

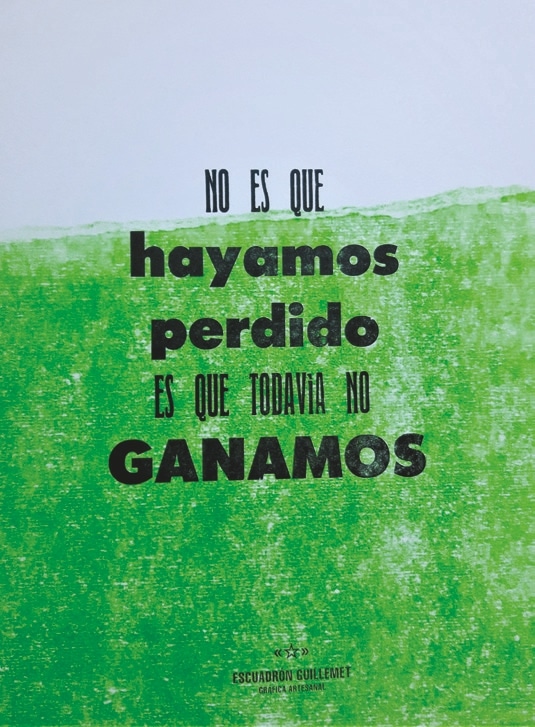

By the way, El Giro Gráfico is subtitled Como en el Muro la Hiedra. This formula refers to the rhizomatic and overflowing way the ivy grows on the wall and how the graphic art multiplies and spreads.

“It is by accompanying events that graphic art replicates, reverberates, reinvents itself. The graphic has always had a political dimension. It has always attended political events or has always been politically charged. I think of the popular silk-screen printing workshops, which were always spaces of multiplication.”

Graphics has to do effectively with the multiple, with the collective, and the exhibition captures it very well.

We are very interested in thinking about the relationship between graphics and the multiple or collective. Still, above all, in the context of the urgent, that is, when an event occurs. Because it is when accompanying events that graphic art replicates, reverberates and reinvents itself. The graphic always had a political dimension. It has always attended political events or has always been charged with politics. I think, for example, of the popular silk-screen workshops, which were always spaces of multiplication.

But although our way of working in El Giro emphasizes those ways of doing graphics, it does not stop at exhaustively compiling what happened in each country of the continent. Instead, we sought to generate conceptual nodes that would allow us to link some of those productions -or cases, as we call them- that could quickly have occurred in another country of the region. It is not that on one side there is Peru, on another there is Colombia and on another there is Argentina, but rather these manifestations coexist, they are grouped by nodes.

Let’s talk about some of the themes that articulate the curatorial proposal.

For example, one of the nodes is ‘‘La Demora,’ which has to do with ways of doing things that take more time that is linked to slowness. A case in point would be embroidery in Nicaragua. And by the way, what relation does embroidery have with graphics? And the fact is that we think of graphics as something much more overflowing, precisely. Now that the exhibition is in Mexico, we are organizing a Latin American meeting of embroiderers there. It will take place in May if everything goes well. The idea is to think about all these procedures, these ways of making, and what political processes accompany them in each country we will be able to bring together.

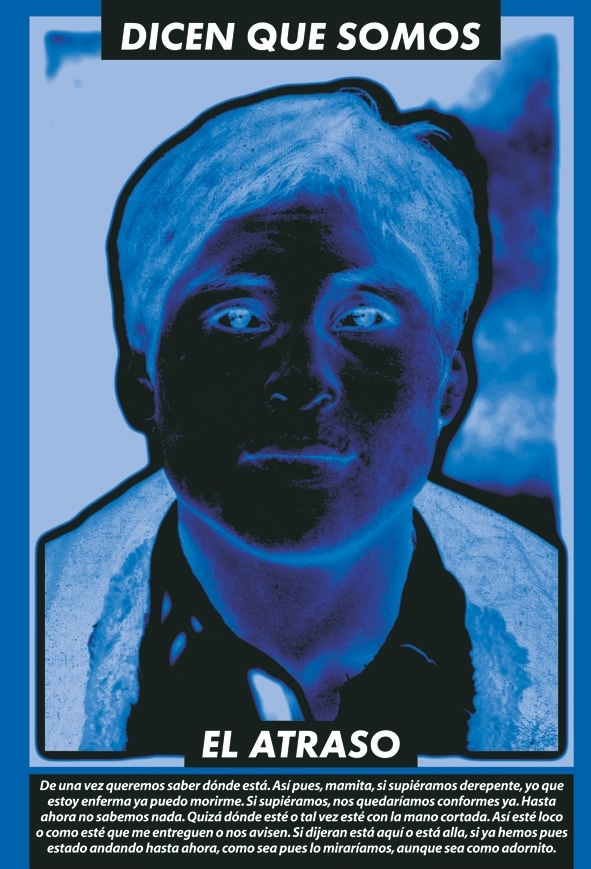

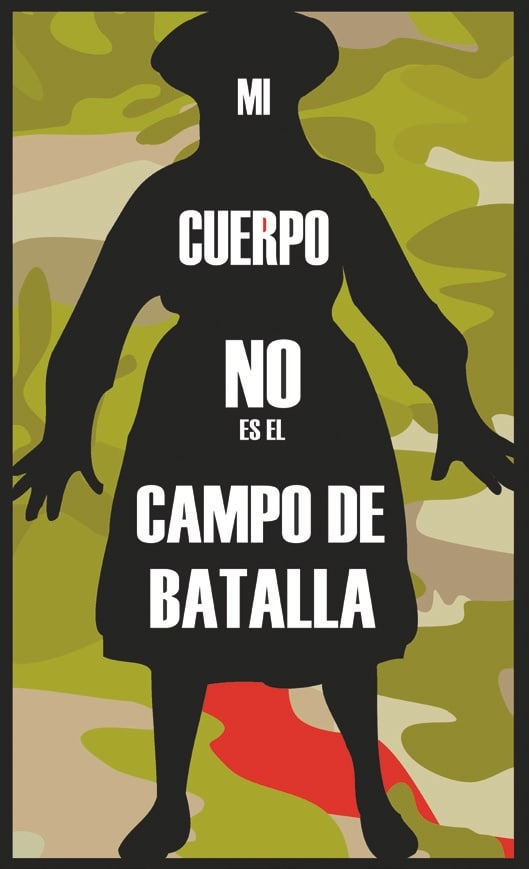

Other node, such as ‘Persistencias de la Memoria’, gather works related to detainees and the disappeared in countries like Uruguay, Argentina, or Mexico. ‘Territorios Insumisos’ refers to much more localized problems: it is the graphic art linked to the struggle for territories, either from environmentalism or, for example, in the case of the Mapuches, to a demand to recover their lands. These nuclei operated for us as interrelated spaces that allowed us to organize the question of the graphic.

What is the role of photography in this “graphic turn” in Latin America?

Look, this is a good question. We had not been asked about it before. Some photographs accompany or document something of what can be seen in these productions. In other works, photography has a central role. The most straightforward case is that of Uruguay, where banners with photos of detainees and the disappeared were used. Or the case of Juan Angel Urruzola, also Uruguayan, who works with passport photos, the same ones that can later be seen on those banners and that somehow mark, and situate the disappeared and the places where massacres occurred in Montevideo. They are working to map violence from the photographs.

Often the photographic dimension appears in work with faces or with victims of repression, sometimes explicitly, and other times they are works based on photography. Urruzola’s example is very clear because it is a gigography in which a space in Montevideo appears, the photo card, and then some mosaics in which the photographic process is precisely the photographic dimension of the work.

Why, when asking the question about the graphic, did you not consider developments related to the Internet or the visual culture of social networks?

That is another question that came up during the research: how far do we extend the dimension of the graphic? Do we link it to the networks? There was a decision to make. We contemplated, for example, the possibility of including a work that uses facial recognition technologies. We also thought of incorporating the virtual. That is, it’s not that we didn’t want to, but we left it by the wayside.

What we did do was to create a space called ‘El Aura del Presente,’ in which we projected videos, things taken from the Internet, such as clips of the theses of Un Violador en Tu Camino in different parts of the world, or street records of the campaign for abortion in Argentina. That is to say, graphic campaigns that circulated on the Internet and that have been incorporated in an audiovisual way.

Some of these campaigns emerged from the Red de Conceptualismos del Sur’s social networks because we often call for them through statements or appeals. For example, we have recently called for a graphic campaign to accompany the process in Peru. The idea is to circulate the images through our networks and then integrate them into ‘El Aura del Presente.’ It is a way of responding from the exhibition to live events. Because museum work is never fast enough. You have a deadline and have to close the proposal many months in advance, so you always miss the present. And tomorrow, you have a coup d’état in any Latin American country.

Where can the exhibition be seen after Mexico?

The official itinerancy of El giro gráfico ends in Mexico. But we are thinking of doing something similar to what happened with Perder la Forma Humana, which was first at the Reina Sofia and then had different “unofficial” versions exhibited in several Latin American countries. That is self-managed by members of the Network. It’s not that a museum pays for us to develop the project, but we get funds from outside and do those exhibitions ourselves.

For now, there is a confirmed exhibition in Uruguay. We will probably do it in Chile at the La Moneda Cultural Center. There is also a desire to do the presentation in Bogota, but that still needs to be confirmed.

Can we talk about the following exhibition projects of the Network?

This Saturday, we have a plenary session to review the last year of work. We are in a moment in which, after these mega-projects -The Graphic Twist has been six years in the making, which is no small thing- we have a space to rethink what we have done and to rethink ourselves before starting other research processes. We will see when we close this year of El Giro‘s unofficial itinerancies.