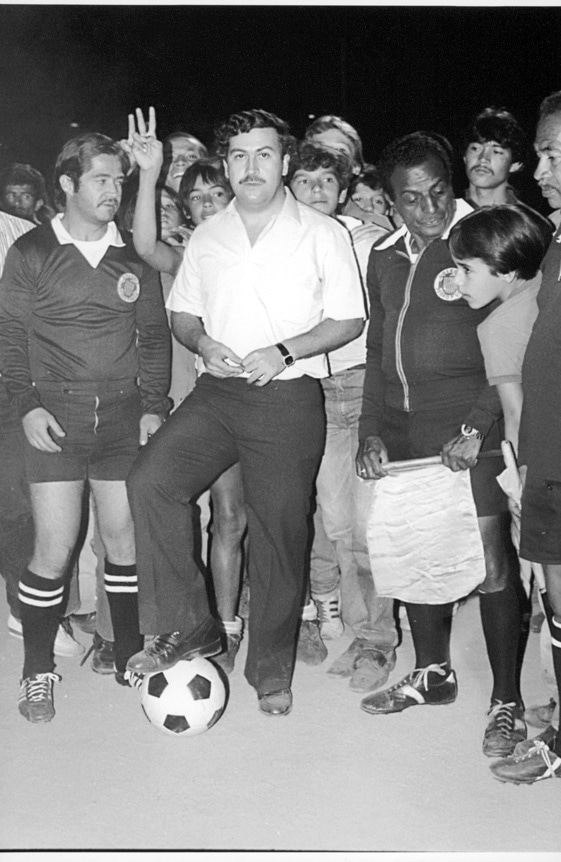

I photographed the birthdays of the most powerful Colombian narco.

In El Chino. La Vida del Fotógrafo Personal de Pablo Escobar, Alfonso Buitrago tells the story of Edgar Jimenez Mendoza, who for years accompanied the quirky life of the Medellin Cartel kingpin and recorded it profusely in images. The book also narrates the M-19 experience, wanders through chess clubs, and even delves into the Colombian porn scene of the early 1980s. It is a different narrative about drug trafficking: one that contemplates the rampant violence of the armed conflict and the remnants of normality, the daily lives of anonymous families involved in the illegal business.

By Alonso Almenara

Edgar Jiménez Mendoza, alias El Chino, has achieved something unique in the history of photography: to meticulously record the personal life of Pablo Escobar – the world’s most famous drug trafficker – and survive to tell the tale.

To Alfonso Buitrago, the author of El Chino. La Vida del Fotógrafo Personal de Pablo Escobar (Universo Centro, 2022), this 70-year-old photographer from Medellín ‘s archive, resembles an immense album of “antisocial pages.”

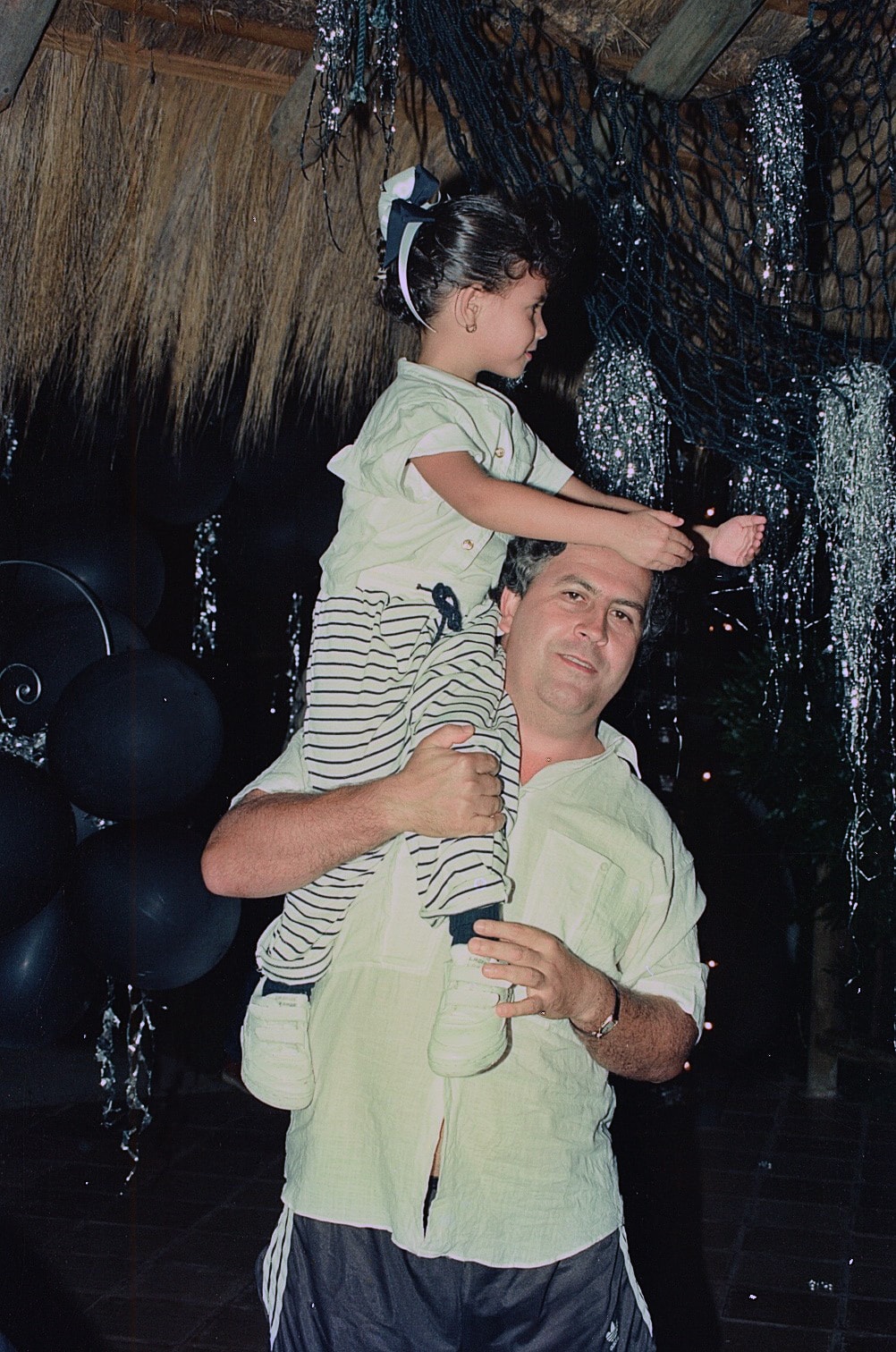

His images are disconcerting, perhaps because they are far from capturing the savagery we usually associate with drug trafficking. “They are the images of a photographer of social events. In other words, they are non-violent photographs,” Buitrago explains. “Many people ask me if El Chino portrayed the victims or the bombs, let’s say, the worst period of the drug war against the Colombian State, and that’s not the case. We are talking about the photographer of birthdays, first communions, marriages, intimate celebrations of friends.”

The book offers a B-side of Medellin’s recent history, composed of a hundred images of Jimenez and a profile written by Buitrago. A story where Pablo Escobar and drug trafficking play a central role, but where the actions of the left and the struggle of the M-19, a guerrilla group of which Jiménez was a militant, or the ins and outs of the social life of the middle class, which often took place in chess clubs, are also recorded.

Many of the characters portrayed in Chino’s photos are anonymous. “There are a lot of characters linked to crime or who had a tragic end because of their relationship with drug trafficking. They were murdered, fell in the war against the State, were killed by the mafia or were kidnapped,” explains Buitrago. Hence the feeling of “antisocial pages.” But what we see most often are ordinary people: the extras who usually walk in the background, people who were not involved in violent acts but who benefited discreetly from the drug business. People found this illegal activity an irresistible opportunity for social advancement.

Buitrago believes that this could be one of the book’s contributions: to open a discussion about coexistence with drug trafficking. Not about violence but about the strange peace that is also possible in a society where the narco is everywhere.

How did you convince Chino to show you his archive for this project? Did he feel that his images told an important story?

I met Chino in 2017 through a job with Jon Lee Anderson, the reporter from The New Yorker, who came to Medellín to write an article about the sort of resurrection of the figure of Pablo Escobar, closely linked to the success of the Netflix series. At that time, Medellín had begun to experience a kind of boom in the memory of Pablo Escobar. John Lee came to explore that topic, and in that reportage, we met Chino.

I immediately became interested in his life. Talking with him, I realized that he had a story beyond having been Pablo Escobar’s photographer. His life is fascinating because it allows me to portray the last 40 years of Medellin’s experience in the war on drugs. From its initial, non-violent facets, which is what I call the “comfortable condescension” or our “idyllic relationship” with drug trafficking, between the late 1970s and mid-1980s, to its transformation into a blood-and-fire confrontation that ended up marking the history of Colombia in the last decades of the twentieth century.

“Chino’s life and his photographs show us the complexity of the Colombian conflict: they record how drugs and drug trafficking end up involved in all political demands and the internal armed conflict. Chino embodies this mix of struggles and ways of confronting the State.”

Do you consider that these images contribute new elements to understanding the history of drug trafficking in Medellin?

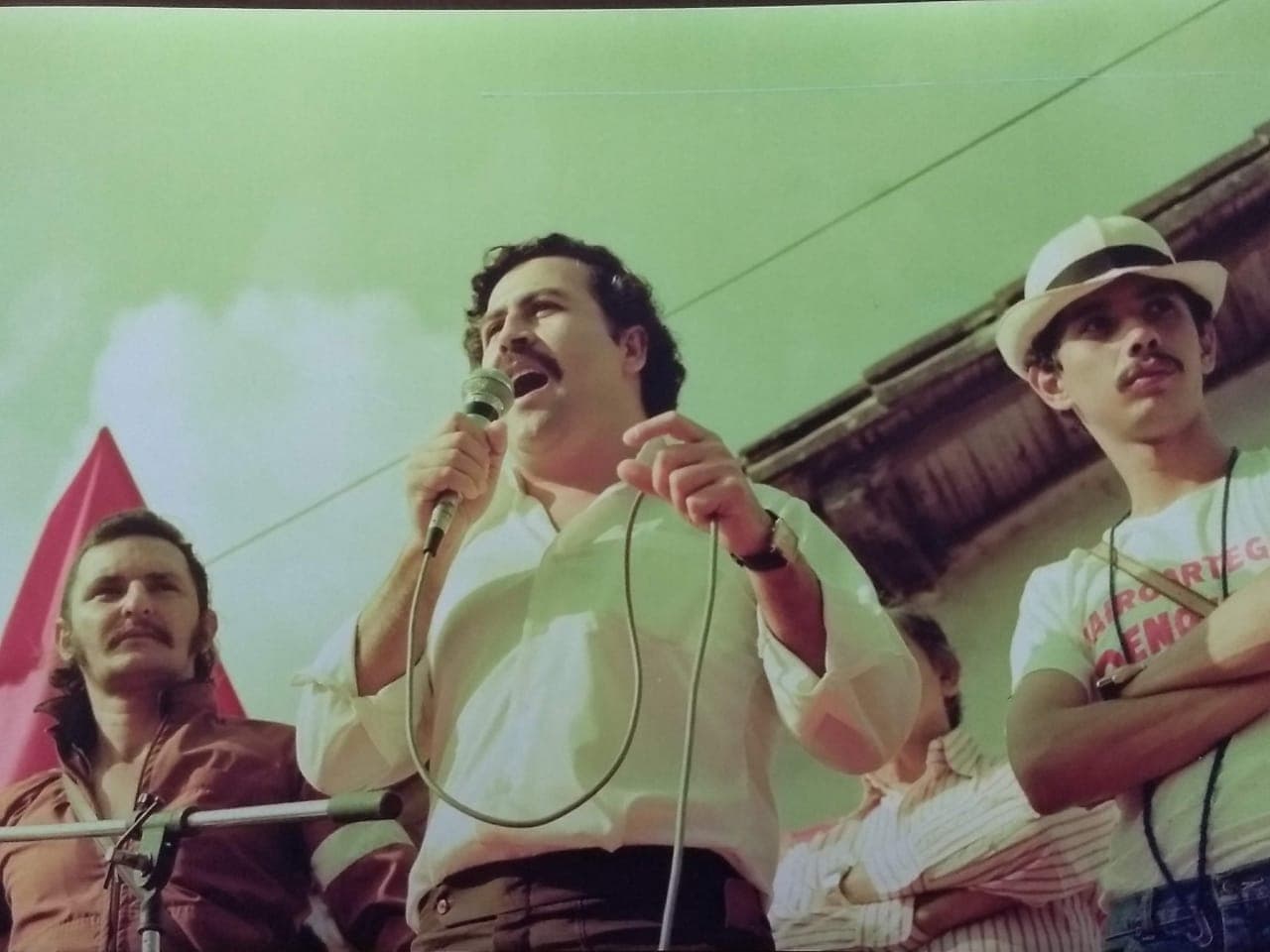

Yes, I think so for two reasons. First, we must not forget that Chino has a facet as a guerrilla militant. He was a political photographer from when he was a militant in the Alianza Nacional Popular movement, and then he transitioned to the M-19 guerrilla movement. He was a member of the Communist Party with founding leaders of the guerrilla.

At the same time, his life crossed paths with Pablo Escobar’s by purely chance coincidences: they were high school classmates. So I believe that Chino’s life and his photographs show us the complexity of the Colombian conflict: they record how drugs and drug trafficking end up involved in all political demands and the internal armed conflict. El Chino embodies this mixture of struggles and ways of confronting the State.

On the other hand, his work offers us a portrait of our coexistence with drug trafficking. The relationship with drugs is usually seen only from the violent side, never from the side of coexistence, of how society benefits from the entry of illegal money that generates a way of life for many people. It is tough to talk about that. It is not accepted, but it happens. And I believe that Chino’s photographs portray it.

How was the process of curating the photographs that appeared in the book?

Chino’s archive is vast. It’s not all about Escobar; it covers both the Escobar family and the Henao family, Victoria Eugenia Henao, who was Pablo Escobar’s wife. Before this project, I had worked with an American photographer named Tom Griggs, who has lived here in Colombia for several seasons. I like his photography, especially his work with his family album photographs, so I asked him to help me curate the book. The director of the publishing house Universo Centro also participated in this task.

The book has about 100 images. The selection includes episodes of Chino’s guerrilla life; there are also photos of many of his friends, leftist militants who paramilitary groups killed. And finally, there is an archive of his relationship with Pablo Escobar and the Medellín cartel.

“How do you have a normal life? How do you keep your memories? How do you keep a photo album when you are the brother, the cousin, the nephew, the brother-in-law of a dangerous criminal? It would help if you had a trustworthy photographer to pretend that this life is normal. Well, that role was played by Chino.”

Why did Pablo Escobar have a photographer who followed him everywhere? Was it simple vanity, or was there another intention behind these photographs? Did El Chino know what he was doing?

Escobar was vain, no doubt. He liked to have photos of his hacienda, his animal collection, his eccentricities, and his economic success. But his peculiarity concerning other big drug lords is that he also had a tremendous public conscience. He had political ambitions from very early on. But this would not have been possible if there had been a period in which drug trafficking was an activity with only a developing moral stain. There was a lot of acceptance. It was a relationship that was not yet marked by unleashed violence. So Escobar always had political ambition, and political ambition requires a photographer. And it just so happened that his school friend was a photographer.

Chino was perfect for that role because Escobar trusted him; he was someone he could have at home with his friends, someone he could call at any time. How do you have an everyday life? How do you keep your memories? How do you keep a photo album when you are the brother, cousin, nephew, or brother-in-law of a dangerous criminal? You must have a trustworthy photographer to pretend that this life is normal. Well, Chino played that role.

Chino must have an extraordinary personality to have been able to fulfill that role and get out of there alive.

You asked me a while ago if Chino was aware of what he was doing. He was thoroughly knowledgeable; he knew who Escobar was. We are talking about a particular photographer with a political background. A photographer who was part of a guerrilla movement knows what clandestinity is. He knows what it means to keep a secret. He knows the risks of informing someone. He is not an innocent photographer with a little camera who will collect ten photos. El Chino fit in very well because he understood the subway world and what it was like to work with people who have a double life. That gave him an excellent understanding.

In reality, El Chino is an entirely loyal person. He was always very dedicated to Pablo Escobar, and his affection for him was sincere. El Chino admired, above all, the political Escobar. He believed in the cause and still firmly believed that Escobar’s commitment to the poor, his social discourse, was genuine, not a pose of convenience. He realized in the long run that Pablo Escobar was a criminal and became violent, but Chino has always said that getting out of it was not easy with the file he had. You don’t speak to a capo: “hey, you became very violent. I don’t want to continue. You go on with your life and let me. I have been photographing your family for ten years; I have photos of all your children, you go on, and I’m going home”.

People are sometimes very naive, especially foreigners. Many foreigners have interviewed Chino, and I dedicate a good part of the book to understanding the moral judgment of those who ask him why, when he realized that Escobar was killing people, he did not retire. It causes me the utmost tenderness.

There is a detail of Chino’s life that I do not want to leave out. He is also a pioneer of pornography in Colombia.

A chapter is dedicated to that facet of his life, which is not minor. I confess my frustration with the book is that Escobar eclipses those other facets of Chino. Particularly that of pornography. Because the history of porn in Colombia is quite fascinating, the first magazines of this type appeared in the 1980s. The pioneer of these publications was a man very close to Pablo Escobar, Edgar Escobar. They share a surname, but they have no family relationship. Edgar Escobar wrote short stories and poetry. He was a man close to the cultural environment who crossed paths with Pablo Escobar and became his public relations man. He was, let’s say, the intermediary between journalists and Escobar; he helped write letters and communiqués. Edgar Escobar was the entertainer of the stages when Escobar went to the neighborhoods. Some say he was a kind of biographer, which is why he followed him everywhere.

This gentleman fulfilled that role, but it turns out that he also had a penchant for erotic literature. In the mid-’80s, he partnered with an American pornographer and founded a pornographic audiovisual production company called Trópico Producciones. At the same time, he created a publishing house and started editing porn magazines. He also made the first homosexual porn magazines in Colombia. He was a very pioneering guy. And since Chino was Pablo Escobar’s photographer, he quickly got involved. He had no moral qualms; he accepted and was part of the first stage of Edgar Escobar’s porn magazines.

One of your interests for several years has been to promote discussions and new narratives about the memory of the narco. Why do you consider this important, and against what kind of narratives do you position your work?

This book is not unrelated to a proposal that we started working on several years ago with a Dutch sociologist named Gerard Martin. We created a platform called NarcosLab because we had incredible frustration that Medellín was an epicenter of the global narrative around a drug lord but that there was so little information about the meaning of the memory of the narco in the city. The drugs war narrative is centered on the traffickers or the victims of drug violence, always avoiding coexistence with the business.

In reality, we don’t often see the daily lives of many people who are not necessarily victims or have tragic stories to tell. We are talking about ordinary people, people involved in a business as if you were starting a travel agency. Sometimes you do well; sometimes, you do poorly. If you are astute and understand the company, you end up with ten travel agencies, a certain comfort, and a certain wealth. And that is not talked about in all societies that have drug trafficking. People do not recognize that relationship with the business because there is a shame. After all, it is illegal because you do not want your children to know that you pay for their university with drug money, your wife to know that her lovely house is drug money, or that your inheritance for your grandchildren is drug money.

But that’s how it is. The reality is one. We believe that this has to be talked about because otherwise, we will not understand the relationship between this illegal business and the role of our countries in this international war against drugs as long as we do not understand that drug trafficking plays a social function. If we do not recognize it and do not talk about it, the circle of violence will continue unchanged with its tragic consequences at human costs.

That is what we call “new narratives.” We want to promote the recognition of what it means to have a society in which the drug business plays an important role. And from that perspective, Chino is very particular because he has no shame in discussing his relationship with Pablo Escobar. It is tough to find a person from Escobar’s generation who has been close to the business, has survived, and speaks openly about what that period of his life was like.

You told me that you met Chino in 2017 when Jon Lee Anderson came to Medellín to write about the resurrection of Pablo Escobar’s image and the popularity of “narcotours.” What is the significance of this phenomenon of glamorization of the narco in Colombia?

I think it has been a wasted opportunity for Medellin. I do not understand how the city has a leading role in the memory of a drug trafficker like Pablo Escobar, but does not have a leading role in the discourse of the failure of the war on drugs. Something that is now being discussed in Washington or Mexico. The International Forum on the War on Drugs’ Failure should occur here. Medellín should convene intellectuals from around the world to discuss these issues. But at the same time, the city feels ashamed. Its political elites are ashamed of that role; they prefer to be victims and not to talk head-on about the meaning of that business in our society.

That is not easy. There is a massive burden of stigma. Medellín society feels very offended, perhaps because its pain has not been recognized. Between 1984, when Pablo Escobar’s confrontation with the State began, and 1993, when he was killed, there were more than 40,000 violent victims in the city. It is an outrageous figure. Medellin feels that this pain is trivialized. This aesthetics of evil, of entertainment, of fascination with murderers does not do justice to the history of the city.