Landscapes of an agonizing river

The Riachuelo River, which flows into La Plata and gives its name to the famous neighborhood of La Boca in Buenos Aires, is one of the most polluted places on the planet. In the project Río Invisible (Invisible River), Alejandro Kirchuk combines photography, video, cartography, and virtual reality to tell the stories of the people who live there: the Argentine photographer hopes that his work will help to understand why many of these people are reluctant to leave the place and why it is a crisis that has to be solved urgently.

By Alonso Almenara

Alejandro Kirchuk has lived all his life in Buenos Aires. He is also a soccer fan: this is how his relationship with the Riachuelo River began. “It’s behind Boca’s stadium, which is the club of my love and the one I see every two weeks when we play at home,” he says. “The Riachuelo has that sentimental connection with a lot of people.”

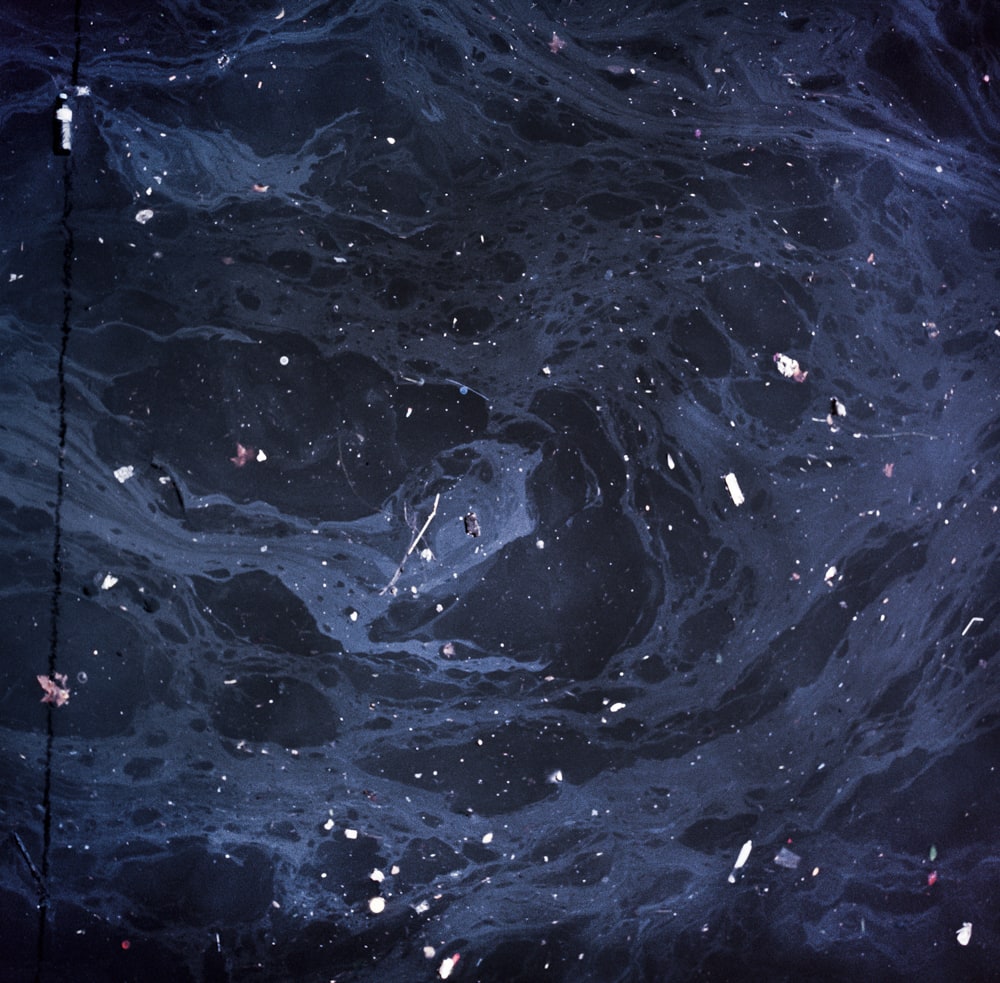

But the Riachuelo is also the scene of Argentina’s most extreme environmental crisis due to the extraordinary concentration of sewage and industrial waste in its waters. A crisis that also has enormous sanitary, economic, and housing consequences: the Riachuelo basin is one of the most densely populated areas in the country, with some 6 million inhabitants, 15% of the Argentine population.

The data speak for themselves: 25% of children living in slums along the river have lead in their blood, and an even higher proportion suffers from respiratory and gastrointestinal diseases. In 2008, an Argentine Supreme Court ruling declared that 17,700 families living near the Riachuelo were in a maximum sanitary emergency and should be relocated to a safer place. Only 30% of these people left the area. Many families are waiting to be relocated. Many others want to stay by the river, where they have built their homes, lives, and identity.

Kirchuk is a photographer whose work focuses on long-term documentary projects. With Never let you go, a project about Alzheimer’s disease, he received first prize in the category ‘Stories of everyday life’ in the World Press Photo contest in 2012. But when he started to become interested in the situation of the Riachuelo, already a decade ago, he understood that it was not only going to be a long-term project: to embrace the complexity of the problem, he would have to rethink his way of working and, eventually, start migrating towards other formats.

The result is the Río Invisible project: through an interactive website with photographs, videos, data visualization, a virtual reality experience, and a map with geolocated content; this work explores the multiple factors that contribute to the river’s pollution, as well as the social and environmental consequences of the crisis.

“The idea is to close it this year and have it exhibited in 2024 or 2025,” Kirchuk says. “First of all, here in Buenos Aires. And let it be in some space in front of the river.” As part of the preparations for a new edition of ECO, our meeting of photographic collectives that this year will focus on ecologies, territories, and communities, we talked to Kirchuk about this experience that led him to relate for years with dozens of families living on the riverbank, to win the Fullbright scholarship and even to change his way of looking.

How was the Rio Invisible project born?

It was almost ten years ago. I had just come from working on a long project about my grandparents, something very personal, and I was at a time when I felt like starting a new project. Still, I felt erratic in the transformation process of the way I photograph. It was at the end of 2013. In those days, I came across a publication by a global environmental institute that had ranked the ten most polluted places on the planet. And in that ranking was the Matanza Riachuelo Basin. What I remember thinking at that moment is that no porteño would be surprised to hear that the Riachuelo is a dirty and highly polluted place. But what shocked me was that the Matanza Riachuelo basin came after Chornobyl in the ranking. It is a sudden realization of the scale of the tragedy. The name project is Río Invisible precisely because the problem is invisible.

And it is curious because although we all know that the Riachuelo is polluted here, people are still determining exactly what is happening with the river and its situation in depth. If you ask people, they relate the river with La Boca, which is the place where the river ends, and which is a very touristic area. But what happens along the river in those 60 kilometers is unknown. So that’s where my interest arose. And the fact that it was such a broad and complex subject allowed me to face this personal and authorial transformation process. As I was working, I was also transforming as a photographer. You can see that in the project.

What explains such alarming levels of pollution?

The popular imagination of the river’s contamination concerns what happened two hundred years ago rather than what is happening today. In other words, the leading cause is industrial pollution from the leather factories along the river. However, the tanneries have been fairly controlled in recent decades, and many factories have been reconverted. The main pollution factor today is sewage pollution, which needs to be better known. But it is also a consequence of the social decomposition of the country and the region since it involves the installation of informal settlements that dump their sewage into the river or streams that end up in the river. That is why solving the problem is so complex: informal settlements continue to multiply, especially in the southern part of the city, which is the most neglected area.

The industrial component of the problem is not so simple either. In recent years, with the creation of ACUMAR, which is the Matanza Riachuelo Basin Authority, the industries have been controlled more. Still, it is a work that has to be continuous and always faces resistance because it costs money to the State and the companies. You should start announcing that you will audit, and automatically, everything will be solved. This issue is a constant tension in a country in a permanent economic crisis, such as Argentina.

“When you start working on a subject of this nature, you tend to focus on some small aspect of the story. I had a slightly bigger ambition: I wanted to discuss all the complexities I encountered. That’s when I ran into a limitation in photography and felt the need to explore other possibilities documentary filmmaking offers. I started to migrate towards video and not only video: the project also includes an interactive map.”

Let’s talk about your photographic treatment of the subject.

When I started the project, I was at a moment when I felt a bit saturated with the photographic process, so many shots, so many photos. So I bought a medium format analog camera and decided to do the project with that format, making creating images more thoughtful.

Compared to other projects of mine, the images in this work are a little less dynamic and a little more programmed. Always consider that I come from the world of documentary photography and photojournalism and that there is something that I never want to lose. It is a project that fusion between photographic reportage and something more conceptual.

And on the other hand, what happened to me is that, as I was saying, I found myself with a vast subject and very difficult to cover. When you start working on a topic of this nature, you tend to focus on some small aspect of the story. I had a slightly bigger ambition: I wanted to discuss all the complexities I encountered. That’s when I ran into a limitation in photography and felt the need to explore other possibilities documentary filmmaking offers. I started to migrate towards video and not only video: the project also includes an interactive map. I wanted to take advantage of the space of the basin, the river, and everything that happens around the river. I found it interesting to work on this theme from the cartographic, using a map that is updated with new information.

This willingness to expand the project also interested me in other disciplines and media: I presented the work to a training grant, the Fullbright grant, and I went to the United States to learn virtual reality. Now I’m finishing a part of this project which is a virtual reality film about a boatman who takes people from one side of the river to the other, crossing the only place where the river can be navigated. All these possibilities have presented themselves to me thanks to the breadth of the subject, but it also has to do with my interest in exploring these new formats. So I think that the project will end up condensing all these things.

Río Invisible includes video recordings of testimonies of people who live along the Riachuelo. Have these people seen the project? Have they commented on it?

The project is not finished, so the protagonists have not yet seen the finished version. But I have built up a relationship with some of these people over time, so they have seen some of the material and are more aware of how the project is going. In some cases, my photos have even helped them to file a court injunction since many of the lands where they live are in dispute.

There were also people with whom I related more deeply. One of them is the Botero I told you about. His name is Gustavo. I met him in 2014, and we shot the 360 film last year. We generated a personal bond there because it’s a relationship of several years. I did some of the early photos of the project, like the portrait of the twins on Gustavo’s boat. And in between, I was the photographer for his daughter’s quinceañera.

His boat crosses from Maciel Island to La Boca, passing right between the two bridges, the old Transbordador Bridge and the Avellaneda Bridge. It is the only point that can be used because about forty years ago, the river’s navigability was prohibited as a measure that, at the time, was a safeguard against the environmental catastrophe. Today the river can be navigated, the authorities are navigating it, and there is an intense fight among some civil associations for the river to be navigable again. What is believed, and it is evident, is that when a river is not navigable, it is no man’s land, and it is less cared for; it is less appropriate. And that if the river could be navigable again, there would be more movement, generating more positive movement around the area. Recently there were some hearings in which the issue is being discussed, which seems to be the key.