The heavy backpack of a war photographer

Jaime Rázuri, a Peruvian photographer for AFP, has just published the photobook Como un Relámpago en el Cielo. He brings together two decades of work capturing the ins and outs of political violence in countries such as Peru, Haiti, Iraq, and Palestine. In this interview, Rázuri talks about his motivations, the role of photography in the construction of historical memory, and what he experienced during his kidnapping in Gaza in 2007.

By Alonso Almenara

It should not be surprising for a war photographer to feel disturbed by the nature of the images he produces daily. In the case of Jaime Rázuri, the doubts began to come a few at a time as he came to understand his inner motivations for exposing himself to violence in a systematic way. The big question for Rázuri, at 66 years of age, is not whether this line of work has desensitized him to horror. On the contrary, what interests him is to finally make peace with his intense, irrepressible attraction to death.

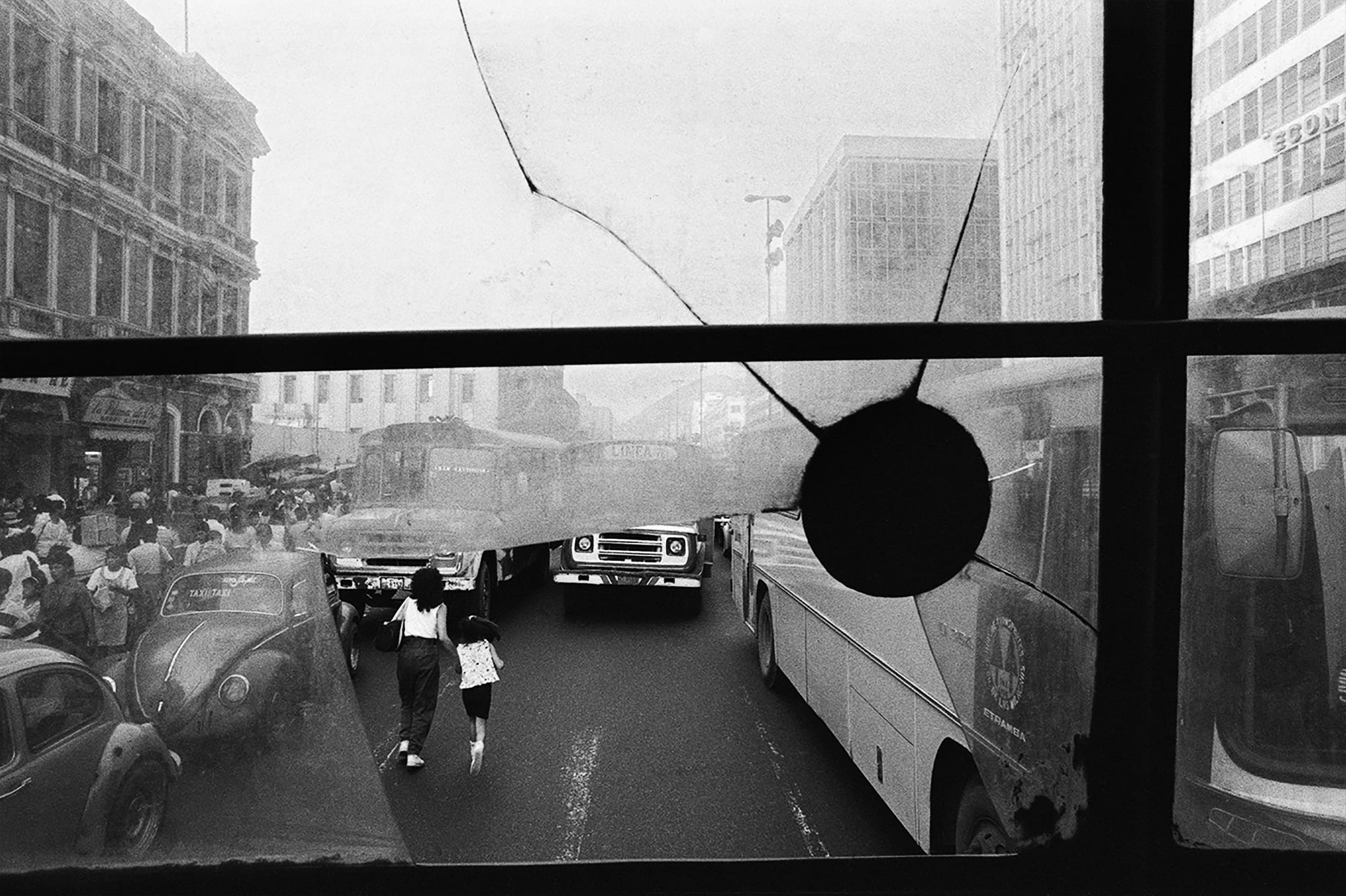

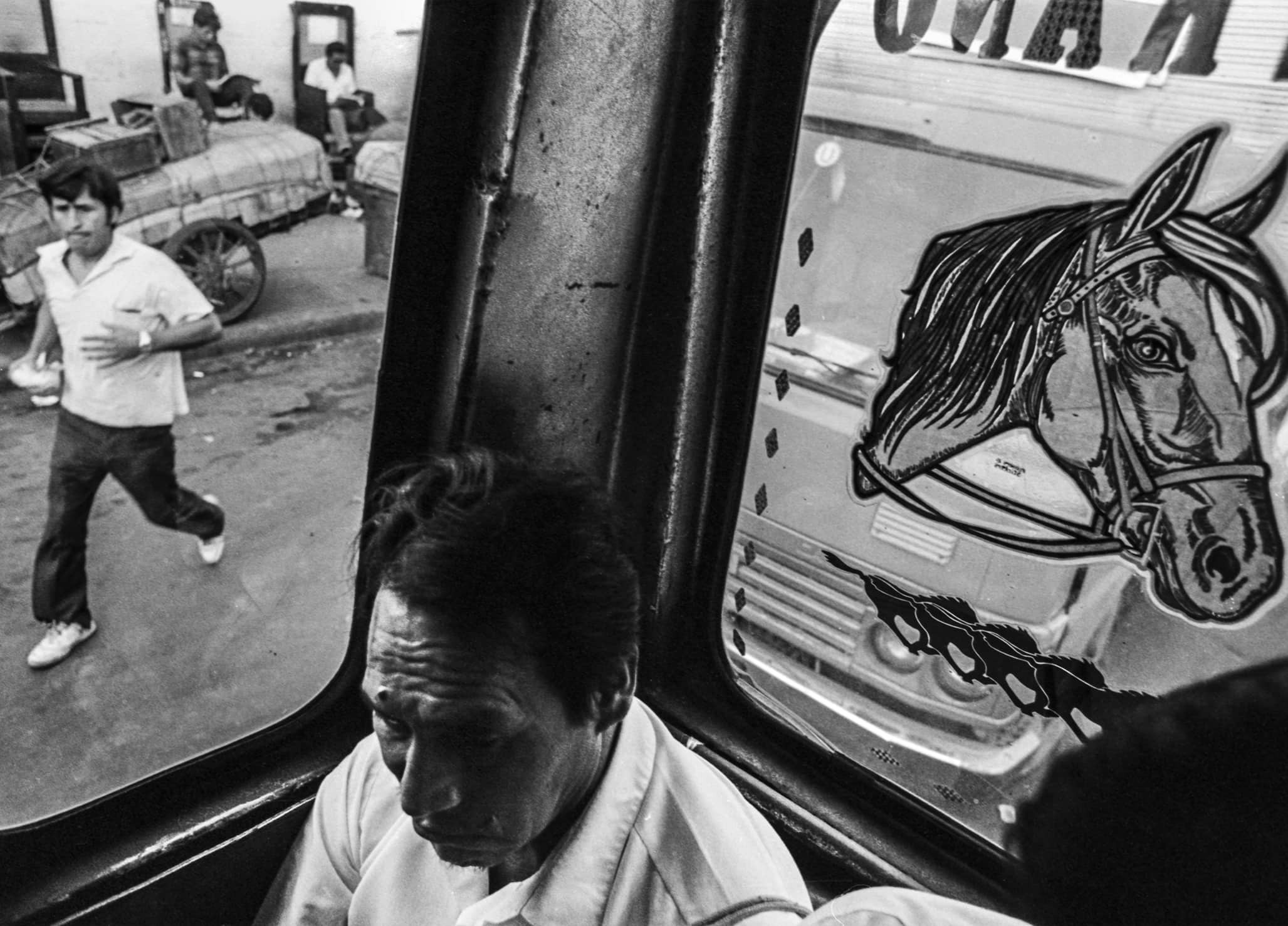

Born in Callao, Rázuri began his career in press photography in the late 1980s. He worked for the VSD supplement of the newspaper La República and the magazine Caretas. During those years of internal armed conflict, the Peruvian State pitted against the terrorist groups Sendero Luminoso and MRTA. In that context, Rázuri captured unforgettable images, such as that photo showing the aftermath of the attack on Lima’s Canal 2 in June 1992. Against buildings in ruins due to the explosion, we see a man being comforted by another. His delicate figure bends in pain amidst twisted iron, almost as if his body were imitating the construction in the background, on the verge of collapse.

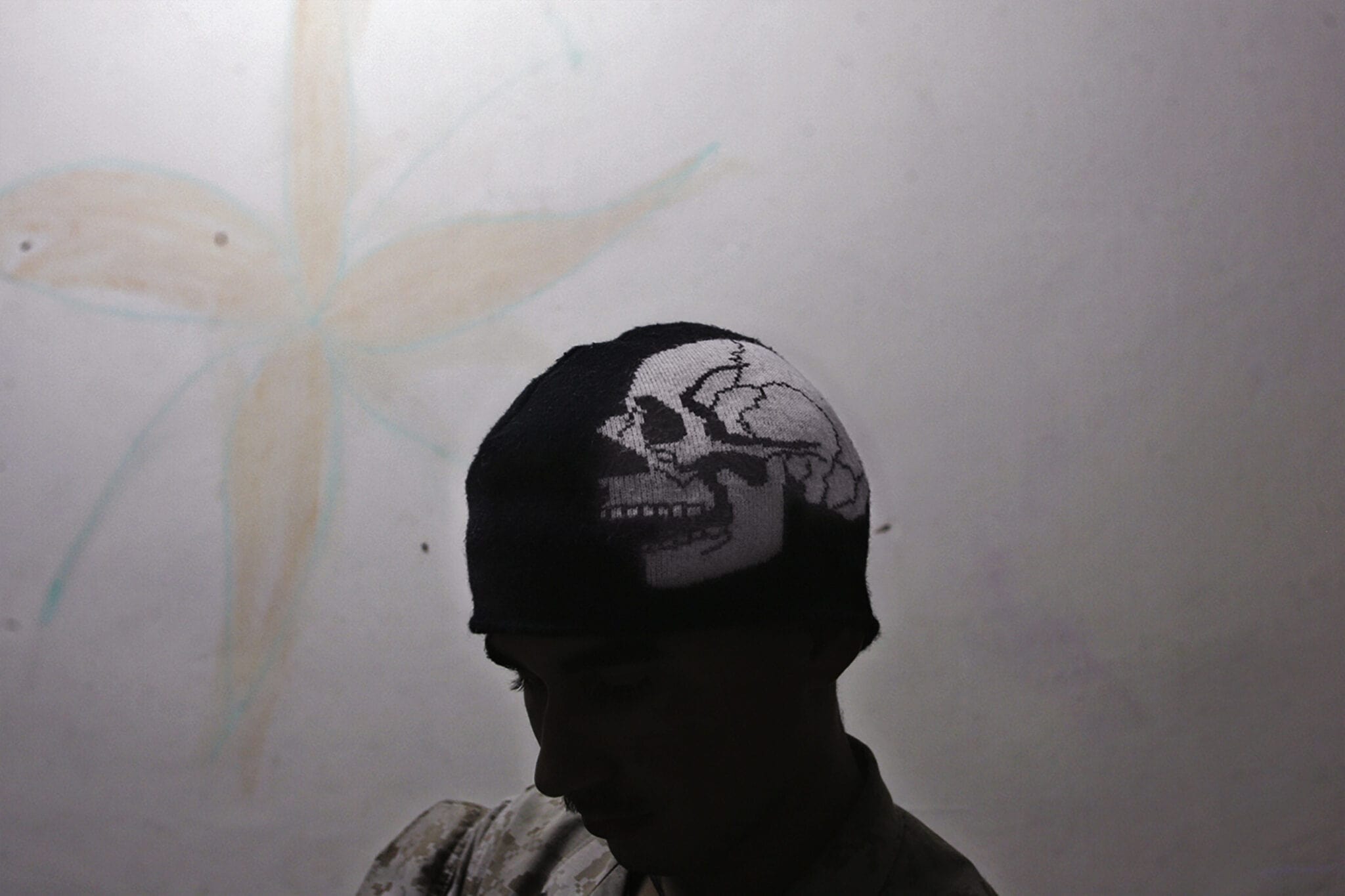

In 1994, Rázuri was a photographer for the France Presse agency in Lima, which led him to travel to photograph conflicts in various Latin American countries, also Germany, the United States, Iraq, and Palestine. The photobook Como un Relámpago en el Cielo brings together his work as a press journalist, presenting a selection of photos spanning from the late 1980s to 2009, when the Peruvian photographer stopped working for AFP. Edited by photographer Giancarlo Shibayama for the independent label Kwy Ediciones, it is a book Rázuri has been thinking about for years as a settling of accounts with his demons.

“Look at the cover. Look how thick it is: it’s a laminated cardboard cover,” says Rázuri, proud of the result. “And the cover is raw; it has no fabric lining. Giancarlo and I wanted to give the book those sensations of roughness and hardness. Besides, it’s a big book. It has the exact size of another book I have at home, an old photography manual written by an English photographer named Michael Lanford. That book is like a brick. I was interested in transmitting that same sensation, not only of a big thing but a heavy thing, like a backpack or a story that one carries”.

Rázuri has a thousand such stories: his kidnapping, which occurred in Gaza in 2007, in the context of the offensive to take control of the city that pitted Fatah and Hamas against each other. In this conversation, the photographer reflects on two decades of work: what his work encompasses in thematic terms and the reasons that led him to seek danger.

Why did you decide that the time had come to bring together your work as a press photographer?

The story begins with an invitation to make an anthological exhibition of my work, but in reality, I had already been thinking about it subconsciously. When they proposed it to me, it wasn’t the right moment, but it was what motivated me to take on this project that ended up becoming a photobook.

It’s a complicated story because the exhibition was originally going to take place within the framework of the Lima Photography Biennial, and, as you know, the Biennial no longer exists. Then I worked on the project with the Peruvian-North American Cultural Institute of Miraflores, but it also fell through, partly because of the pandemic. Then came the idea of the book, which a university would publish, but the institution finally backed out. Then Giancarlo Shibayama and I ended up doing it practically alone. Then came an economic stimulus from the Ministry of Culture and a couple of other supports, with which we finally got the publication off the ground.

So it has been a bit like letting myself be carried away by the process that started with the idea of the exhibition, but also taking advantage of the fact that I had already been thinking about it. I began writing texts some time ago. I think I just needed a push to revisit these images.

What kind of texts were you writing?

I wrote a more or less long text about my kidnapping. And I also had another series of texts that could accompany the photographs and vice versa. Whether internally or externally, circumstances were pushing for the book to happen.

Como un Relámpago en el Cielo combines works that document convulsive situations in which you have been in direct contact with different types of violence. How have you dealt with this constant exposure to extreme situations?

On the day of the book presentation, I told an anecdote that has to do with this. It happened to me in 2005 when I was photographing a dead person on the asphalt in Iraq, in front of what had become a barracks during an operation the Americans were carrying out in the north of the country. These people had not stopped at the orders of the Americans, so they were shot. I see a dead person on the runway. I approached and went around the car this person had been in, and the idea was to take a classic photo: the soldier and the body. But at the moment, I’m looking for the angle, and I feel that something is close to me, at the height of my head. I turned around and saw the hand of a second person, also dead, who had fallen inside the truck. His hand was reaching through the railing of the vehicle, brushing against me. That, for example, is a straightforward encounter with explicit violence.

I could mention many such situations. For example, I have witnessed people being shot in the head. In 1994, I saw a person killing another person simultaneously in Haiti. But perhaps the most powerful thing was to have been next to a journalist, turned around, walked a few meters for two or three minutes, returned to the place, and found that journalist dead. That also happened in Haiti in 2004.

These are moments when you feel you are going from the fiction, or the apparent fiction, of photography, what could be called a sort of game where you believe that nothing serious can happen, to such hard blows as suddenly hearing gunshots and finding a dead colleague next to you. The other violent experience that marked me is, of course, the kidnapping itself.

Can we talk about the context of your kidnapping?

It was in the new year of 2007. I was in Gaza looking for a poster that I was told showed Yasser Arafat and Saddam Hussein together. Hussein had been executed shortly before, on January 31, 2006, so the idea was to photograph the atmosphere around that event. I spent a few days looking for the poster because I knew no Arabic. I depended on a couple of people, a driver, and a translator. We found the sign, I took the picture, and on the way back, entering the building where the France-Presse office in Gaza was, the translator turned around when he heard a strange noise. I also turned around and saw a man armed with a Kalashnikov, dressed in black, with a beard, young. He grabbed my arm, and that’s where the whole story began. Where did he take me? I don’t know.

“I think I have sought to expose myself to these situations somehow. You don’t just go out to photograph what’s going on, but you gravitate toward violence. Something inside you is pushing certain buttons, so this ends up happening.”

How long were you kidnapped?

Six days. There was a negotiation involved that I never knew how it happened. The group that kidnapped me was a faction, I don’t know if it was political, but it did not belong to either Hamas or Fatah, the main political movements in Palestine. It was a faction a little bit on the fringes of the conflict between the two groups, and their objective was to change the focus of these movements so that they would deal with what they thought was the most important thing, which was the confrontation with Israel.

Six days later, I don’t know why I was released. As I was saying, I never found out about the negotiations. Of course, I did everything I could, which was very little, to get out of there. But going back to the subject of the unconscious, I think I have somehow sought to expose myself to these situations. It is not that one simply goes out to photograph what happens, but that one gravitates toward violence. Something inside you is pushing certain buttons so that this ends up happening.

This chronicle is fascinating, not only because it documents a shocking event but also because you manage to connect the kidnapping with other intimate aspects of your life.

The chronicle starts with a scene where I am beside my father, who is dying in a hospital bed. This is the most personal part of the book, the autobiographical part that relates to this desire to photograph the violent. There is a big question that my father leaves behind when he dies, which is about affection, those distances that sometimes occur between parents and children and that are not completely resolved when one of them dies. The gap is left there, and you must respond to it somehow.

After the kidnapping, I realized that what motivates me when I photograph is this search for closeness. In the text, I write, in fact, about the few moments in which I received affection from my father. But I don’t know if this is the only driving force of my work: obviously, I have also made very reflective images around violence, for example, the photo of the dog that appears in the book. It’s a very curious photo that asks what this thing you’re looking at is. It’s like trying to see through an X-ray and not a photograph.

I want to talk about what is happening in Peru. In the late 1980s, you became very interested in the issue of cultural identity in the country: specifically, mestizaje and Choledad in Lima. Given the current crisis in Peruvian society and the polarization between the Andean south and the capital, do you think the narrative of mestizaje as a form of integration has been exhausted? Can we still speak of mestizaje positively, or has this idea served to hide tensions that have not really been resolved?

They have not. If they were, we would be looking at entirely different circumstances. I may be going to go out on a limb here, but there has been a search that has been more intellectual or anthropological than real. There has been a desire for miscegenation as a sort of product of migrations and for the result to be the identity of Peru. But this has later been decanted, showing that we are an utterly fragmented country with many countries inside it. And a country that needs to come to terms with itself.

I remember the first time I experienced this radical diversity that Peru has. It was in 1994 when it occurred to me to report on the Ashaninka patrols. I had already been to the jungle several times, but only to cities like Pucallpa, Iquitos, and Tarapoto. This time I photographed a couple of communities called Polleni and Betania in the central jungle of Junin. There I suddenly felt like I was in another world. I didn’t recognize what I was seeing. It broke my brain a little. I needed to understand that this could also be Peru. I think living in Lima, especially in districts like Miraflores or San Isidro, blinds you a little.

Your work has been included in the collections of institutions such as the Photo Library of the Museo de Arte de Lima and the Yuyanapaq project of the Truth Commission. What do you think about the role of photography in the construction of historical memory?

It is fundamental. The issue is that we have an ancient culture that comes from orality. At a certain point in the development of society, that orality and its derived forms, such as literature, began to dominate the landscape. However, reporting events verbally or through writing has a problem: it is straightforward to manipulate the facts. On the other hand, the image has the character of a document. Although it is a record made in a way that often implies a commentary, there is a level at which what you are seeing is what has happened. The image must have a central role in preserving memory, whether discussing the photographic or moving images.

I would like to end this conversation by returning to the book’s problems in getting out, especially from institutions that promised support and finally withdrew it. Do you consider that in Peru, there is an essential tradition of the photobook? Or is the photobook still something that is not well understood in Peruvian society? What is its situation in the public debate?

I haven’t really thought about it, but I feel that we are not a society very fond of reading or books in general. On the one hand, what is interesting about the photobook is that its aesthetic has certain similarities with that of comics and graphic novels, making it more digestible than traditional literature. This aspect could help the photobook to be incorporated much more into society. However, there is still a great distance between a Hermelinda or Condorito joke and a photobook. To consume this type of material, it is necessary to understand that it is a visual narration, which implies learning the language of the image, at least a basic knowledge of the language of the photographic image. The photobook works in specific sectors: the photographers’ guild, artists, and intellectuals. But it is still a considerable challenge to get out of this small ghetto to reach other sectors of society.