Machos, Violence, and Propaganda: How to Dynamite the Image of a Narco-Country

In Colombianización, Nadia Granados assaults the audiovisual imagination on which the identity of her country is built. In an acid critique that uses everything from Narco telenovelas to reggaeton, she combines video clips, installation, and performance to break into pieces the Colombia Brand, that decorative fiction that “tries to sell a country that does not exist.”

By Alonso Almenara

Every country brand is a sum of clichés, and there is no better example of this than Juan Valdez, the emblematic brand of Colombian coffee. The character that embodies it was created in 1960 by the National Federation of Coffee Growers and became a landmark in the history of advertising: it did not matter that a foreign actor, the Cuban-American José Duval, played him. As if it were a kitsch production from the golden age of Hollywood, the origin of Colombian nation branding is tied to this laughable and exotic figure: a mustachioed and smiling peasant with generic Latin features, accompanied by his mule Conchita, with the Andean mountain range in the background. Half a century later, the audiovisual imagination of the “coffee country” took an expectant turn with the campaign Colombia is passion, which inaugurated 2005 what today is officially known as Marca Colombia. While the advertising of Juan Valdez promoted an export product, the campaign launched by the government of Álvaro Uribe accompanied the Colombian neoliberal shift with an aggressive promotion of the national territory. The objective: is to attract tourists and foreign capital and to counteract the toxic radiations of drug trafficking and paramilitary violence on the country’s reputation.

Nadia Granados has constructed her work as a series of wild interventions to dynamite that propaganda. Associated with the character of “La Fulminante” and recognized as a key figure in the Latin American post-porn movement, the Bogota-born performer has questioned the forms of violence that cover up the narcotic state advertising, using the tools that popular culture puts at her disposal: the imaginary of cabaret, the language of soap operas, B-movies and pornography. Her first performances were deeply rooted in the struggle for women’s rights and sexual dissent in a society fractured by the violence of the armed conflict. But her character had no difficulty crossing borders: the virulent sexuality and macabre humor of “La Fulminante” made her an Internet phenomenon.

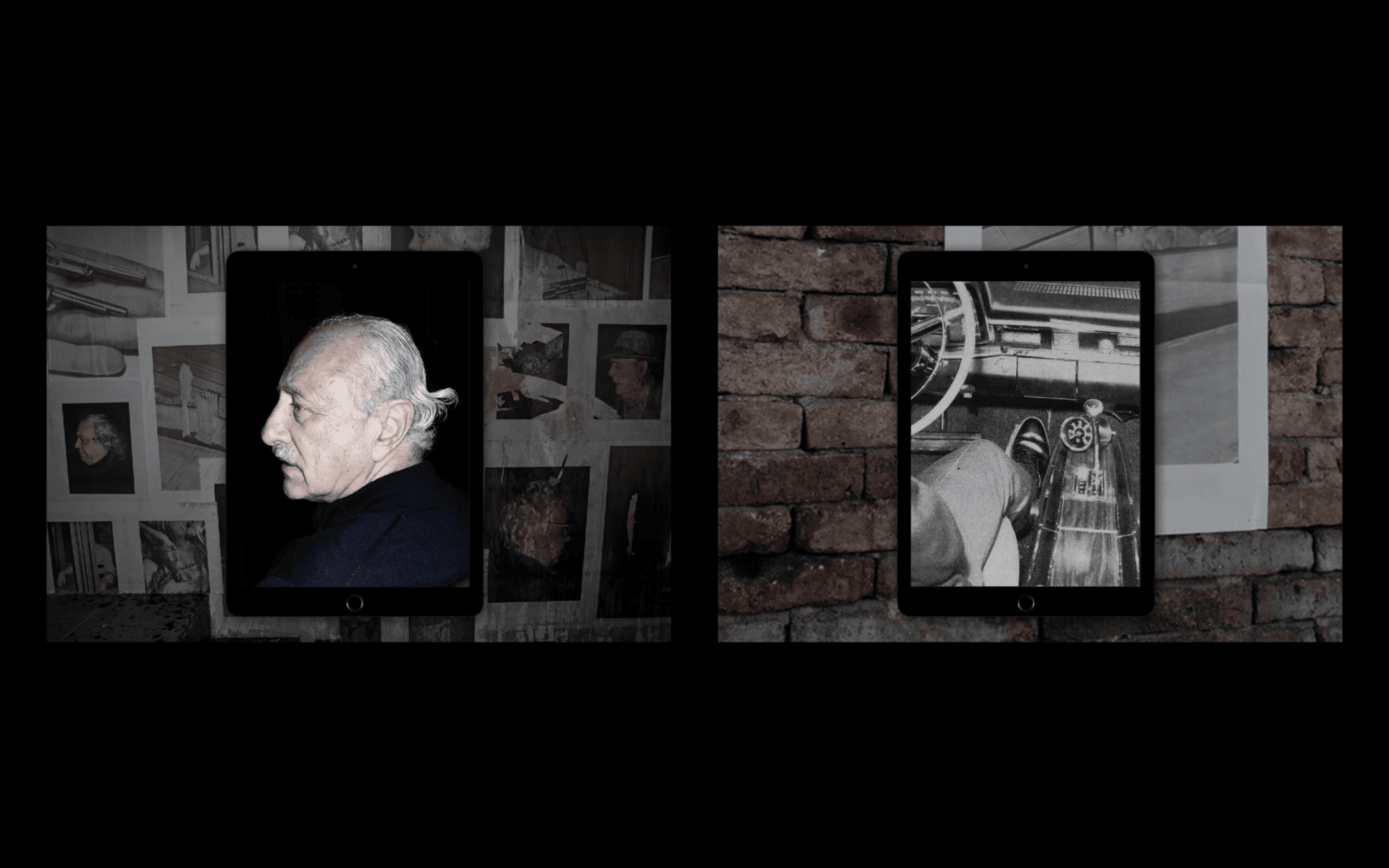

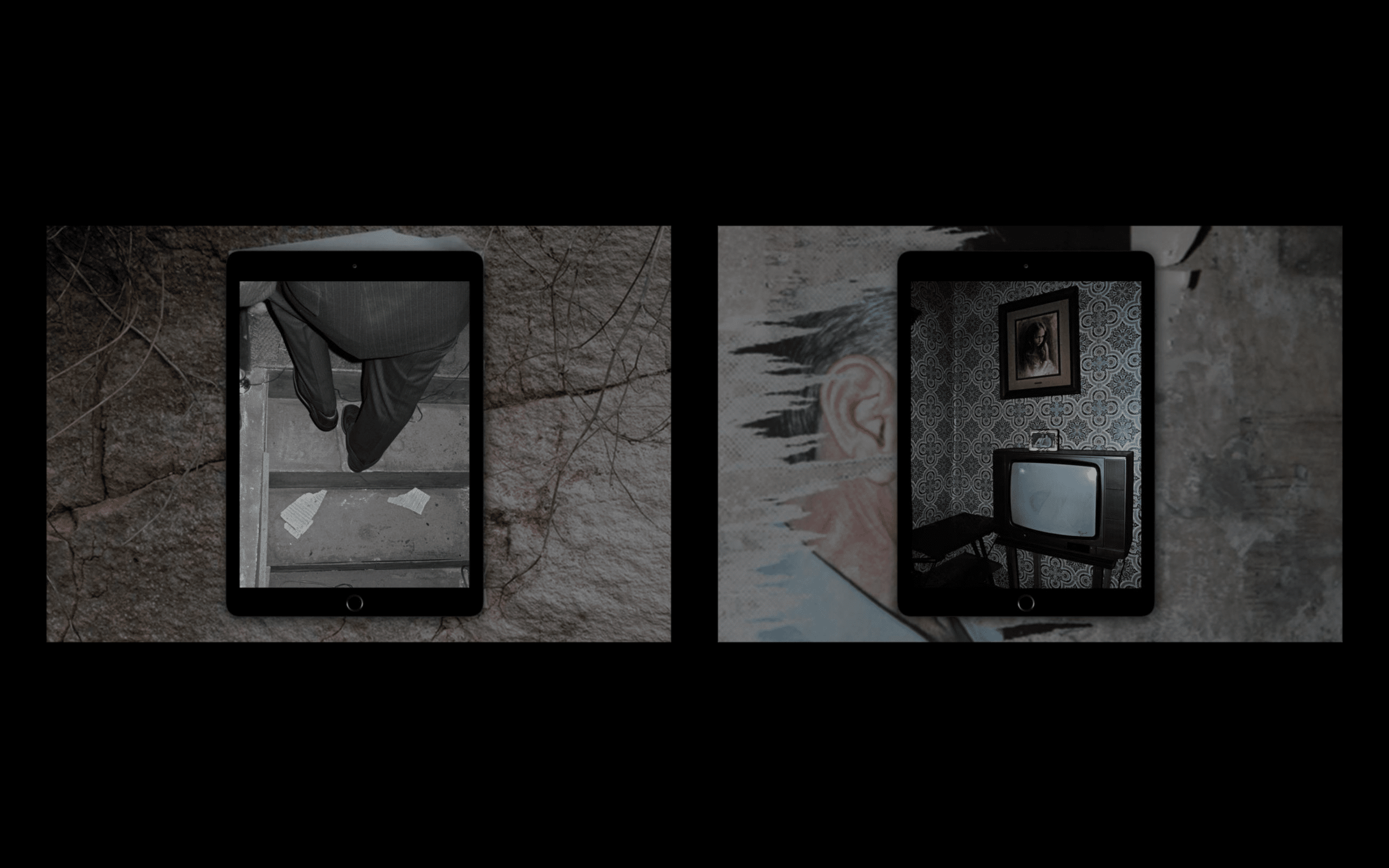

In Colombianización, Granados returns to the arena to broaden the scope of her struggles. Pornoterrorism and drag are still present, but this time they are used to operate an ambitious deconstruction of Colombia’s recent history. The winning proposal of the XI Luis Caballero Award, granted by the Mayor’s Office of Bogota, is essentially multiplatform: it is a website, a series of street performances and an exhibition at the Santa Fe Gallery which brings together video clips, settings and what the author calls “political cabarets”: a sort of shock therapy to get out of the placid dream of Marca Colombia.

Image: Nadia Granados

Let’s talk about the word “Colombianization,” What does it mean to you?

I don’t know where this word comes from, but it started to be used in the nineties, mainly around Mexico. It was a term used a lot during the government of Felipe Calderón, when explicit and grotesque violence broke out, and specific practices linked to Colombian drug trafficking, such as motorcycle assassinations, were exported or became transnational. The word is used in a derogatory way to refer to the process by which a country becomes more violent in a context marked by illegal drug trafficking and the emergence of mafias linked to governments.

What was it about this concept that interested you, and how did the idea for the project come about?

Reflection on this word was one of the triggers for my master’s thesis, which I called Colombianización: exploración audiovisual en torno a un fenómeno cultural tipo exportación. It is a text in which I combined several of my interests and which was the basis for the project I presented to the Luis Caballero Award. One of those interests is what we call here “export-type”: those products that Colombia exports and contribute to shaping the country’s identity.

Another interest was Narco telenovelas and the kind of discourses that these productions mobilized around the narco. I was very interested in how Narco telenovelas began to position and validate violent male figures such as the boss, the hitman, the paramilitary, and the businessman. Powerful characters who have done a lot of damage but of whom Colombians feel a kind of national pride. And I was interested in combining those ideas with an exploration of the Marca Colombia, a propaganda campaign that, in my opinion, tries to sell a country that does not exist. Or a country reduced to decorative elements, such as flowers, emeralds, happiness, and beautiful women, as if Colombia were a paradise ready to be filled with tourists and foreign investors.

One of the problems I find there is that this image was created thanks to a previous process of “pacification” that resulted in profound transformations in the territories. Many people were displaced from the country’s rural areas so that everything would be ready to be sold.

“One of my interests was to show that the idea of ‘Colombianization’ falsifies the problem of violence in this country because it reduces everything to illicit drugs. This way, grave crimes end up being hidden, such as forced disappearances and state terrorism. It’s as if the Narco issue were used to cover up everything else.”

Photo: Mónica Torregrosa – Santa Fe Gallery Archive- IDARTES

You are denouncing, in a way, the country’s neoliberal shift in the early nineties and its aftermath.

My project questions how this country became “Colombianized”: it was not an accidental process but a project planned by right-wing administrations, which has generated great difficulties in terms of human rights, inequality, and violence. I have always thought that violence in this country does not come from anywhere but results from multiple unresolved violence. We are at a moment in which it is important to point them out and to point out those responsible. And I believe that many of us are in this process of denouncing, raising our voices, and disrespecting these people.

What role does drug trafficking play in the official discourse on Colombia?

One of my interests was to show that the idea of “Colombianization” falsifies the problem of violence in this country because it reduces everything to illicit drugs. This way, grave crimes end up being hidden, such as forced disappearances and state terrorism. It’s as if the narco thing serves to cover up everything else. Even today, it is taboo to say: “there was genocide in Colombia.” Many of us have repeatedly spoken of the 6.402 “falses positive” killed by the Uribe government. Still, we believe that this is only a tiny fraction of the killings orchestrated by the government’s military forces.

Photos: Mónica Torregrosa – Santa Fe Gallery Archive – IDARTES

I am from Peru, a country where branding has practically been naturalized, and where the country brand plays a central role in the production of discourses on national identity. What happens when advertising becomes a state discourse? Is there any risk to democracy?

The origin of the Marca Colombia is linked to the advertising campaigns of Juan Valdez, the Colombian coffee for export. That was the first image, the one that was engraved in the imagination of consumers at a global level. Since then, propaganda has intensified until reaching a culminating point with the Uribe’s arrival to power at the beginning of this century.

That juncture motivated me to start producing art with counter-propagandistic intentions or to understand art as an alternative communication tool. During those years, the figure of Uribe was immersed in propaganda. He looked like an actor: he dressed in ruanas and presented himself as a man close to the people, a Catholic, heterosexual, traditional guy. It was a frightening thing to see because, at the same time there were indications that Uribe was linked to the Medellín cartel when he was director of the Civil Aeronautics. And not only that, but with that image, they tried to cover up all the terror generated by his administration. There were persecutions, extrajudicial executions, criminalization of protest, paramilitarism, etc. That is a part of Colombia’s history that has been manipulated. It is not by chance that the Narco telenovelas began to be broadcasted when Uribe started the paramilitary demobilization. Those programs had one thing in common: they presented the paramilitary as a hero.

The Uribe government also launched the campaign Colombia es pasión, a phrase you have incorporated in your song “Brandaland.”

Colombianización includes four video clips made by Raúl Vidales. The music was produced by Bclip, a reggaeton and urban music producer who helped me a lot to condense the texts of my thesis to transform them into songs. “Brandaland” is a dembow, super fast and loud music. What interested us was to use rhythms that are very much associated with this country and that we like a lot but to talk about other things. Reggaeton was also crucial because it is a genre closely linked to the narco aesthetic, that mafia aesthetic that shows gangsters squandering money that you don’t know where it cames from. The lyrics use slogans from advertising campaigns, such as the phrase “export-type smiles,” which comes from a campaign that says, literally, “here we smile as if happiness could be exported.” That phrase is bullshit, but it represents this type of propaganda. It’s as if smiling is our duty.

Let’s talk about the male figures you parody in your work.

One of the songs on Colombianización is called “Capitalismo gore,” which is also the title of a book by Mexican trans-feminist author Sayak Valencia. That book has been a significant influence on me. I am particularly interested in the relationship that Valencia establishes between illegal trafficking, transactions around death, and the way men construct their identities. She explores how a specific idea of masculinity is strengthened by men’s participation in armies, whatever the side. Killing becomes a job that allows you to enter the capitalist world. It is killing to become a man and, simultaneously, a consumer.

Among the characters I chose to caricature or exaggerate violent masculinity is Broly Banderas, the most famous hitman on social networks. I used a speech of his, which I manipulated and distorted. It is a very cynical speech about why kill for money, which is one of this project’s essential questions. We are in a country full of victims of riffraff like that, hired killers, assholes who take a gun because they are paid money, and they can go and shoot you in the forehead. That makes me very angry, and part of my work has to do with exploring the reasons why these people exist. There’s a whole aspirational system attached to that little man

“I became known with ‘La Fulminante‘, a drag queen that ironizes the construction of exaggerated femininity, very explicit, very sexual. In Colombianización, I wanted to do the opposite. I portray male characters based on the stories of violence that have marked Colombia’s recent history.”

Which brings us to your use of the drag king or the practice of personifying male gender stereotypes through clothing and makeup.

The truth is that I have been practicing drag for many years. I like to masculinize myself; it goes with my personality. It’s a useful thing: by passing as a guy, I can walk down the street without anyone bothering me. Drag has been an essential part of my artistic practice since the beginning. In 2010 I became known as ‘La Fulminante’, a kind of drag queen that ironizes the construction of exaggerated femininity, very explicit, very sexual. In Colombianización, I wanted to do the opposite. I portrayed male characters based on the stories of violence that have marked Colombia’s recent history. The drag king was the tool I used to appropriate those discourses and turn them into a stage act.

What are the “confusing acts of violence” you talk about in the curatorial text of the exhibition?

I speak of confusing violence because we are unclear about where it comes from. For me, my brother’s death at the hands of the FARC in 2001 resulted from rambling violence. We don’t know exactly who is responsible, nor why they did it. A massacre like the one in El Salado, for example, who ordered it? Why? They killed a hundred people in three days. It is known that the army was there, but it is still confusing, mainly because there are no perpetrators and no one pays. The victims are simply taken from one place to another. That is confusing. Some people have been looking for their dead for forty years. Some children grow up without parents, in the middle of nowhere, and no one knows why. That is why the truth is so important. The truth is not only understood, but publicly acknowledged, and those responsible are accused and punished. That is something that has not yet happened in Colombia.

Haven’t the Truth Commission and the Special Justice for Peace brought more clarity and less confusion? On the other hand, taking into account that you have won an official award from the Mayor’s Office of Bogota with a work that denounces influential figures in Colombian politics, don’t you recognize a form of progress there?

About the award, I was lucky. The Mayor’s Office of Bogota is an institution with a certain autonomy, and the jury members are chosen by competition and have total independence. This time they had left-wing sympathies. If they had been from the right, I would never have won. But, beyond that, indeed, the process has changed some things. And not only the technique. We are reaching a point where the truth is no longer in the hands of the State or the big media. The situation was quite different when I started doing radio in the early 2000s. There were no smartphones, and the Internet was beginning to become widespread. One of the things that drove us was to fight against the monopoly of information, spreading other thoughts about the history of this country. Almost 20 years have passed, and now a lot of small independent media have a great reception. Even a YouTuber who criticizes the government from his cell phone can have a million followers. The official versions have been weakened, and the mainstream media are discredited. Don’t forget that feminism has also played an important role, as well as many new questions that this century has brought around the participation of other voices and other ways of thinking in public discussion. You can no longer be a white man putting your paws on everyone else, that’s over. No longer is rape acceptable. No longer is terror accepted as a method of getting respect.

When you were preparing this show, you couldn’t have known that Petro was going to end up being elected president of Colombia. Given that your work denounces speeches and practices of right-wing governments, you must have some expectations of a leftist in power.

Well, I confess: I have admired Petro for more than 20 years. When I was young, listening to him speak opened my mind. I was fascinated by his eloquence, his deep knowledge of this country, and the way he confronted many years the paramilitary system, the genocide, the land problem, and the displaced. I used to watch on TV the congressional debates to listen to him talk about the historical truth. But I don’t have to say I am a Petrista for it to be read or guessed, do I? Now, what do I think of what he is doing in power? I welcome his anti-militarist discourse, the idea that we don’t want more death; we want life.

The necropolitics that makes war a business, which was Uribe’s policy, has to end. I also welcome the fact that Petro did not wait to remove twenty-two generals of the Republic, twenty-two people probably implicated in human rights violations. The military forces need to be cleaned up. Petro has the intellectual capacity and knows enough about this country to make changes quickly, and I believe his hand will not tremble to make them. Besides, Petro will not only be an essential politician for Colombia, but for all of Latin America and even globally, because of everything he proposes regarding renewable energies and the priority of life over extractivism.

But it is not only Petro. Francia Márquez, our vice president, is a person of the same level. This black woman has been a miner, a domestic worker, who emerges from this country’s most radical social struggles, the Afro struggles, the struggles for water, for life. Marquez is also marking this historical moment. She becomes like a light that radiates from here to the world. I think the idea that we are living in a new era is wonderful because we are not going to put up with many things from the past. And part of what has changed is that we have weakened the hetero-patriarchal system from feminism and gender dissent. That Petro is president is a sign that this society is changing. In the end, the important thing is not who represents us in government but all of us living a series of transformations in our daily lives and ways of relating to each other.