Gonzalo Golpe: Does “Latin American photography” really exist?

From Chile, the renowned Spanish editor speaks about the impact of globalization on the continent’s photography, the ethical dilemmas of photojournalism entering the world of art, his vision of photo books, and the new directions in his work as an author.

By Alonso Almenara

How long does a boom last? According to experts, in the case of photobooks, more than a decade. It is relative, of course, especially when this object made of pages pasted with fine paper images is still an expensive and minority product. The undeniable fact is that the nature of photobooks has changed. If it was once seen as a chic object to decorate coffee tables or a vanity project for recognized authors, today, it usually occupies a central place in theoretical discussions about photography. For Gonzalo Golpe, a Madrid-based editor closely involved in this trend, the edition of photobooks is “the spearhead of photography.”

Golpe sees an autonomous discipline within the photographic tradition in the editing, the sequencing of images, and the layout. From his perspective, the role of the editor is discreet but essential in the construction of authorship. A well-made photo book is an exercise in self-definition. In its poetic connections, tensions, and displacements, a singular gaze is materialized more entirely and satisfactorily than any individual photograph could achieve. “What I do is accompany, generate the right questions, at the right time, for the author to empower and take center stage in that process,” he observes. “All my work lies in that awareness and empowerment being rewarding and playful.”

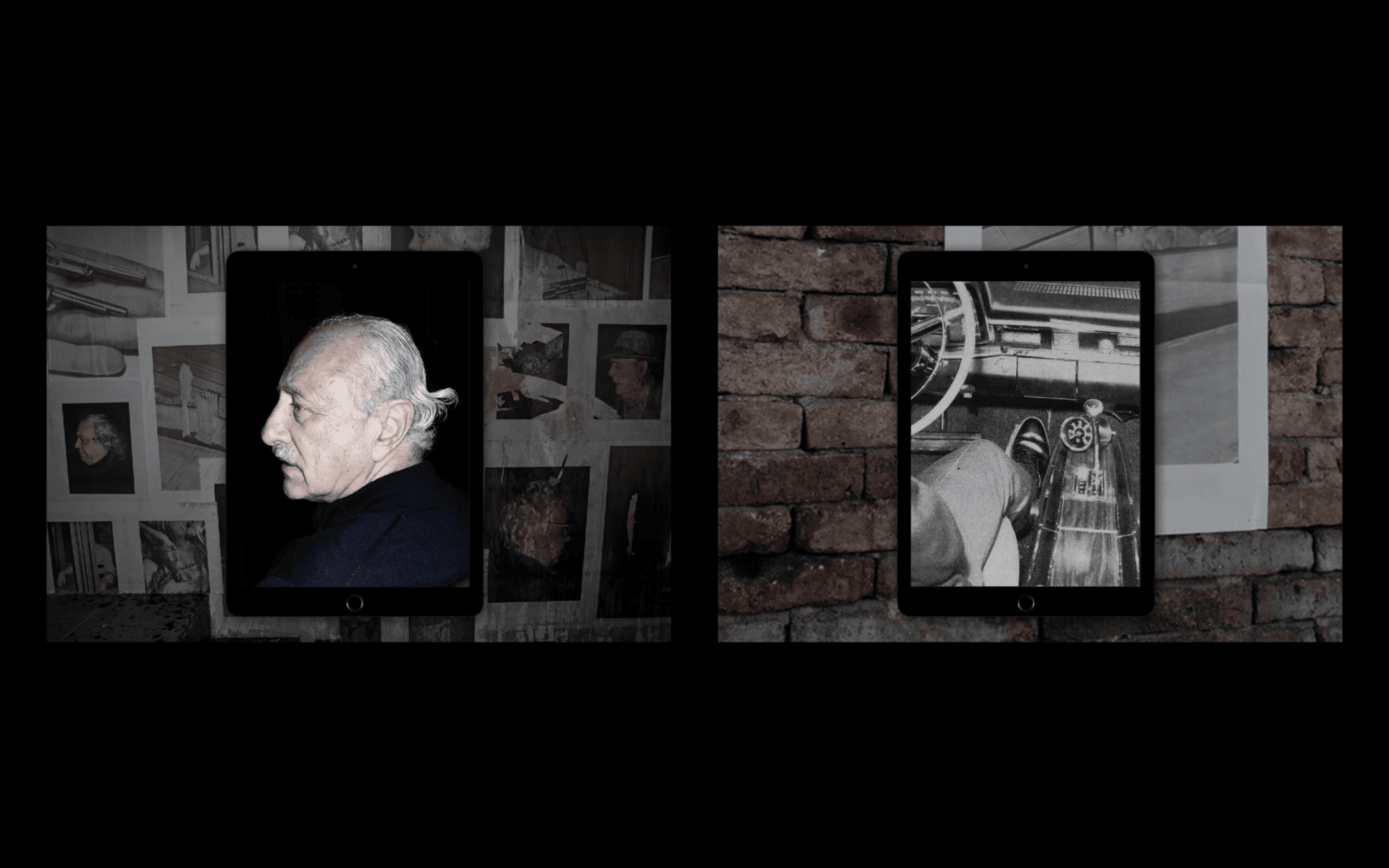

Considered one of the most influential voices in the world of photo editing, Golpe has worked for foundations, museums, publishers, schools, and authors that interest him. He is a member of the scholarship’s selection committee of the Academy of Spain in Rome, which is also open to Latin American candidates. Since 2014 he has been part of La Troupe, a group of graphic professionals who develop visual projects. A few months ago, he settled south of Santiago de Chile, where he had just had a child with his partner. He appreciates the change of pace in this stage of his life: “we live in the countryside, with internet connection but quite isolated, so I continue working, but more focused on pedagogy and my projects.” This relocalization also coincides with his passion for photography made in Latin America. An inexhaustible topic for reflection and controversy.

In recent years, Golpe has collaborated with labels and workshops such as KWY Ediciones in Peru, CROMA Taller Visual in Colombia, SED Editorial, Proyecto Imaginario and TURMA in Argentina, Campo in Mexico/Argentina, among others. Today, he is concerned about what he perceives as distortions in the scene: on the one hand, the push of a globalized perspective in the new Latin American documentary photography and, on the other hand, the ethical problems that loom over the entry of particular journalistic photography into the world of art.

Photo by Laura C. Vela

It is an uncomfortable position. “I can’t help being European, white, Spanish, and male,” he observes. “I have it all to be prejudiced, and I assume it, but the truth is that I have always worked from independence. From the bottom, I consider myself a systemic agent.” If he ventures to comment on the Latin American scene, it is because he is interested, although he does so with respect and admiration for the work that his colleagues are developing. He believes that distance sometimes allows you to see things differently.

You told me that you are surprised that they speak of “Latin American photography” as a whole.

Yes, it has always caught my attention; people constantly refer to it globally, even when speaking in national or local terms. You will not hear an Englishman, a German, or a Spaniard speak of “European photography.” I have always thought that first comes the local, then the national, and finally the international. You can’t compare Mexican photography with Argentine photography or Argentine photography with Colombian photography. What does a photographer from Monterrey have to do with a photographer from La Plata? The best thing that Latin America has are its overwhelmingly rich identity. Spain, in the end, is a small country in many ways. We are 47 million inhabitants. In Latin America, there are 600 million. Mexico, for example, has nothing to envy Spain in terms of photography, painting, literature, cinema, and thought. And that is even though Spain today has the best generation in photography that it has ever had.

As heirs of a Western and Christian way of thinking, we are accustomed to operating in opposition dichotomously. If today’s world has taught us anything, there is no longer black and white; there never was: everything is a mixture shade of gray. Latin America continues to suffer the colonial process’s repercussions, which is undeniable. But there are other forms of colonization related to the functioning of the global economy, which are not always taken into account when using expressions such as “decolonizing the gaze.” Decolonizing is all very well, but from what? For example, the influence of American or English authors in Spain has been brutal; how do we decolonize ourselves from the impact of Alec Soth, Viviane Sasenn, Wolfgang Tillmans, and Paul Graham? The decolonizing processes of the gaze and identity are necessary not only for Mexicans or Argentines but also for Spaniards.

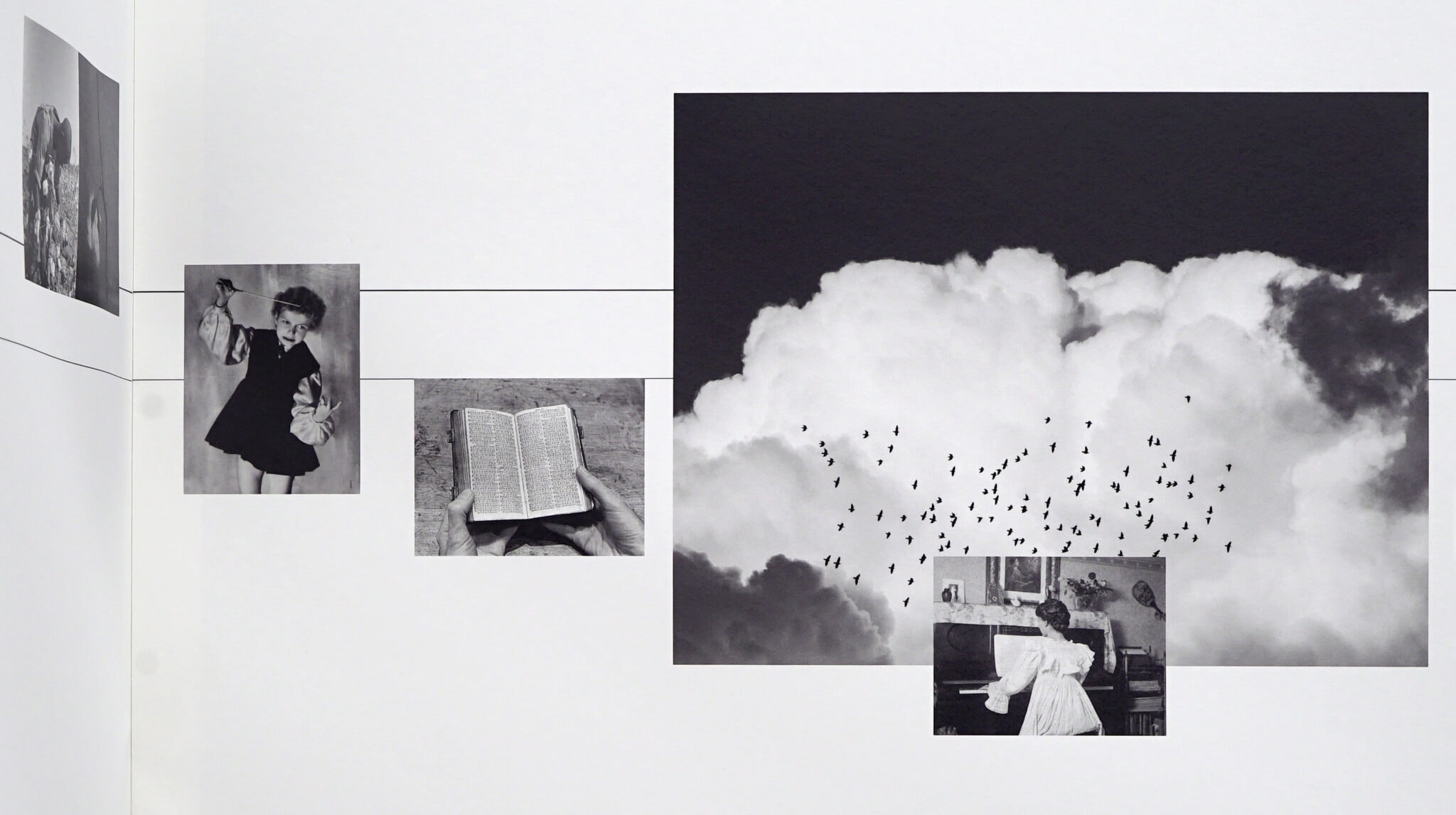

Salvi Danés: Blackcelona, The Portable Photo, Espadaysantacruz Studio, 2016 (ed: Salvi Danés and Gonzalo Golpe)

“When we talk about decolonizing processes in Latin American photography, we are not talking about globalization. You are talking about the colonizing process of Spain or Portugal, but not about the dangers of an image that is being mediated by big players like Magnum or NatGeo.”

In this scenario, a specific danger for photography in Latin America is a certain uniformity of perspective.

When discussing decolonization processes in Latin American photography, we are not discussing globalization. We are talking about the colonizing process of Spain or Portugal, but not the dangers of an image being mediated by prominent actors such as Magnum or NatGeo. Today, a unified aesthetic can be seen in the work of many authors, largely arbitrated by global communication media such as NatGeo. This medium is commissioning projects and allowing photographers to make a living, so the situation is ambiguous. There are aesthetic parameters that need to be answered to, and a subsequent editing process that gives a unified form to the perspective on issues that would deserve a plurality of treatment. Independent agencies and collectives are more necessary than ever today.

Another topic that interests me a lot is the indigenous. In photographic terms, it is a highly conflicting topic, just as it is in other areas of life. It is an open wound that never stops bleeding. It seems we have gone from markedly racist anthropological photography made by Europeans to an idealization of the indigenous and their way of life made by Latin Americans. To what extent the photographers themselves are not exoticizing the indigenous? This is a tremendously uncomfortable question, but the truth is that more photography done from self-reference needs to be included. Where do indigenous or descendants of indigenous peoples do the projects? We mostly have photography in which the indigenous is always connected to the magical world, the symbolic, the Amazonian animals that function as totemic representations. Or with established chromatic codes, such as the expressionist use of contrasting black and white or red filters for night scenes, fire, and stars. Some aesthetic uses constrain the way of photographs, but also a way of working that involves covering a subject for a short period to solve a commission from a foreign media.

In addition, the indigenous person is often presented as the primary standard bearer of the ecological struggle. Not only that: he is a mystic, a spiritual person. Why? There is an infinity of indigenous communities, each one different, in processes of assimilation or confrontation, of reclaiming their identity and independence differently, often invisibilized. Here in Chile, it can be seen in the treatment given to the Mapuche issue: either they are terrorists or green warriors in a permanent struggle with neoliberal governments that do not recognize their historical autonomy. Are there any more positions, no more places from which to speak? When will a Mapuche photographer tell us their stories, whatever they are? Why can’t our work be aimed at making that happen and making it known?

Sofía Ayazargoitia: Every night temo ser la dinner, La Fábrica, 2016 (ed: Sofía Ayarzagoitia and Gonzalo Golpe)

However, you recognize that you are enthusiastic about many photographers from Latin America.

Absolutely. I have been talking about a specific case of documentary photography commissioned by foreign agencies that unify an aesthetic of the gaze, but that cannot speak for all Latin American photography nor for documentary photography. What interests me are the tensions between auteur and documentary photography and how the latter opens up to different approaches and themes. Author comes from auctor, which means “authority.” To proclaim oneself an author is to recognize that you build yourself through your work. It is an exercise of self-government, positioning, and projection of the voice and the gaze. Photography here and there responds too much to other people’s interests. There is no better validation than the one you gain through sincere exposure to what you are and what moves you.

What individualities attract you to photography in the region?

There are many. Among the exponents of the new generation, I am very interested in Jorge Panchoaga. He has generated a great impact, as happened with Cristina de Middel, who aesthetically swept documentary photography. José Luis Cuevas also worries me as much as he fascinates me. Theoretically, no one is writing about photography like Andrea Soto Calderón. What interests me most is what is happening in documentary photography by women, a field of work to which I have devoted my energy in recent years. It’s lovely to see how they are kicking down the door and connecting and supporting each other. They are curators, editors, designers, and authors, and they have their labels and collectives. They work on subjects they feel are their own and do it with interests and time that allow them to be free. It is suitable for me to be close to them, to work for them discreetly, in a second or third plane: it is their time; it is their rules. I am interested in personal looks like those of Fabiola Cedillo, Bernardita Morelo, Juanita Escobar, Marisol Mendez, or Johis Alarcón. The portraits of Leslie Searles. The conceptual constructions of Mariela Sancar. The meticulous work of Lucía Peluffo, more visual artist than a photographer.

Do they have traits in common?

I think they need to respond to canons. Documentary photography is opening up to new modes and realities and now embraces allegory, metaphor, and poetry as narrative mechanisms. Resources that before, due to an excess of rigidity, we would have labeled as unethical. There is also a lot of self-referentiality. The authors that interest me most are those taking documentary photography to a more private, intimate, and personal order.

You mentioned the subject of ethics. Is there another field in photography where ethical problems have come to the forefront?

The friction began in the field of photography linked to the red note. That is when journalistic photography takes a lot of authorship, and one is positioned with the freedom to do whatever one wants at the expense of privacy and the right to anonymity. By its own ontological code, photography demands ethical conditions that other visual disciplines, such as painting, do not have. I think of what Iván Ruiz, former director of the Institute of Aesthetic Research at UNAM, said in an interview when MoMA acquired works by Enrique Metinides, and they became works of art. He noted that aesthetics surpasses ethics, and I think this can happen in other disciplines but not in photography. At least, I would like it not to be so. There are serious problems with the entry of specific journalistic photography into the art world.

Here the issue of intimacy or privacy is important. No one doubts the visual power of Metinides’ photography. If we take, for example, one of his best-known photographs, that of Adela Legarreta, I cannot help but shudder and feel deeply violated in conflict. Such is its power that we forget that there is still, forty years later, a natural person, a woman in particular, with her life and her family. It is not a figuration: it is a life torn out, fixed, and exposed to everyone. Has anyone wondered about her family? About Adela Legarreta’s grandchildren or great-grandchildren, who see how that photo is managed as if it were a Goya painting? The problem is that Metinides’ work (and the entire red note) needs to be more credible in journalistic terms. The real issue is how the art world reconfigures the codes of these images to change our positioning in front of them.

But this is happening globally, not only in Latin America.

It happens most in Latin America and Mexico more than anywhere else. Before Metinides, Alvarez Bravo had already taken a photo of a dead worker in the foreground, one of the first such images. And there are recent examples, such as Fernando Brito.

Let’s talk about this photobook, which opens a different direction in your work.

I have made about one hundred and fifty photobooks with other authors. It is the first time I make a photobook of my own, a hybrid to be more precise; this is a personal response to the purchase of the Metinides archive and how it intimately moves me to value these images, to preserve and disseminate them. One series, in particular, turned me on, from which I got the rage to make this book. In it, Metinides follows a grief-stricken mother carrying a child’s coffin. He stalks her, even confronts her, and makes a frontal portrait of her. This is not journalism: there is no news, and there is morbidity and dehumanization. It is an act of gratuitous violence, not a work of art. I did, then, link photographs I found of a police report (in which no victims are seen, of course) and an ethical confrontation between a fictitious couple. I used the lack of love and an almost soap opera-like writing to discuss the ethical dilemmas in that kind of photograph. The result is a brief but very intense construction, with some closeness to the mystery of the pictures in Blow Up or the structure of La Migala by Juan José Arreola. It is a trap mechanism in which photographs and text hybridize, and in which the last sentence forces one to reread the images, resignifying them. It was recently published by the publishing label Cabeza de Chorlito.

“What interests me most is what is happening in documentary photography made by women. It is wonderful to see how they connect and support each other. They work on subjects they feel as their own and do it with interests and time that allow them to be free. For me, it’s good to be close to them and work for them discreetly.”

I want to end with this question: What initially attracted you to the photobook, and how do you combine working with others with your interests as an author?

I entered the world of photography for several reasons. First, because I am a poet, poetry has to do with establishing connections that are not directly visible between things. When I was studying philology, there was a moment when I stopped writing, and I wanted to be a cartoonist, but I wasn’t qualified. Then I signed up for a photography course and had a second disappointment: I was interested in people but felt uncomfortable photographing them and using them in my projects. Then I tried other possibilities that didn’t work for me, such as photographing through consent. Now I have found another way of working with photography: to do it from the archive. Either by asking other authors to let me work with their images to resignify them in personal constructions or by using royalty-free images as in Atestado or Verba Volant.

Another reason why I was fascinated by the photobook is because of its linguistic ambitions because I saw it as an autonomous discipline within photography. And not only that, it is the spearhead of what photography can do in linguistic, communicative, and expressive terms. Besides, I have always been interested in the book as a support. As an author, I chose it basically for two reasons: freedom and intimacy. One of the most critical moments of the work is the encounter with the other, the moment of reception, and the book is terrific in that sense. In sculpture, the reception of the work is absolutely mediated: you have to be in a particular space at the right moment, and you can’t touch it. The book can skip time and space. When you read a photobook, you activate a dialogue with an absent other who becomes present through you, no matter the distance in terms of time, space, or experiences. At that moment, there are only the two of you. That continues to make me fall in love.