Zahara Gómez dreamed of being a “male photographer”. She says it herself, in masculine, on purpose. She imagined herself recording the war, bringing true to light, and changing the world with an image. But when she began taking photos, she realized that her way was not like she imagined. It was during an exhibition that she asked himself: who goes to museums? Who is challenged by the photography exhibited in these spaces? Then she understood that her search had to be to create in collaboration.

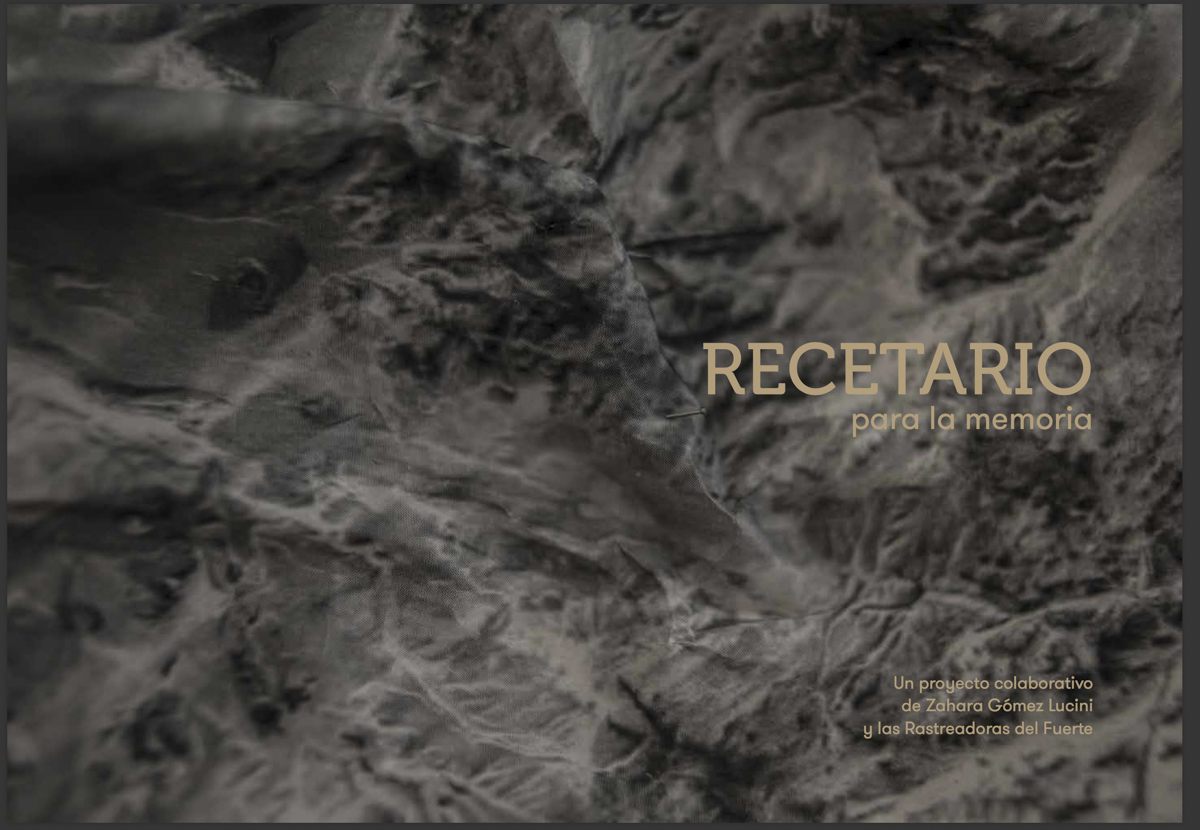

The project she is now in charge of arose in a collaborative way. For years, Zahara had registered the Rastreadoras del Fuerte, the group of women from Sinaloa who come together to search for their disappeared. “We are not alone. Besides God, we have us”, say the Trackers of themselves. Zahara had been in contact with them for years when she asked them what they needed, to give them a hand. They answered “resources”. They came up with the idea: a recipe book with the favorite dishes of those that are missing today. Marketing would be a way to get funding and the book itself, a way to invoke them.

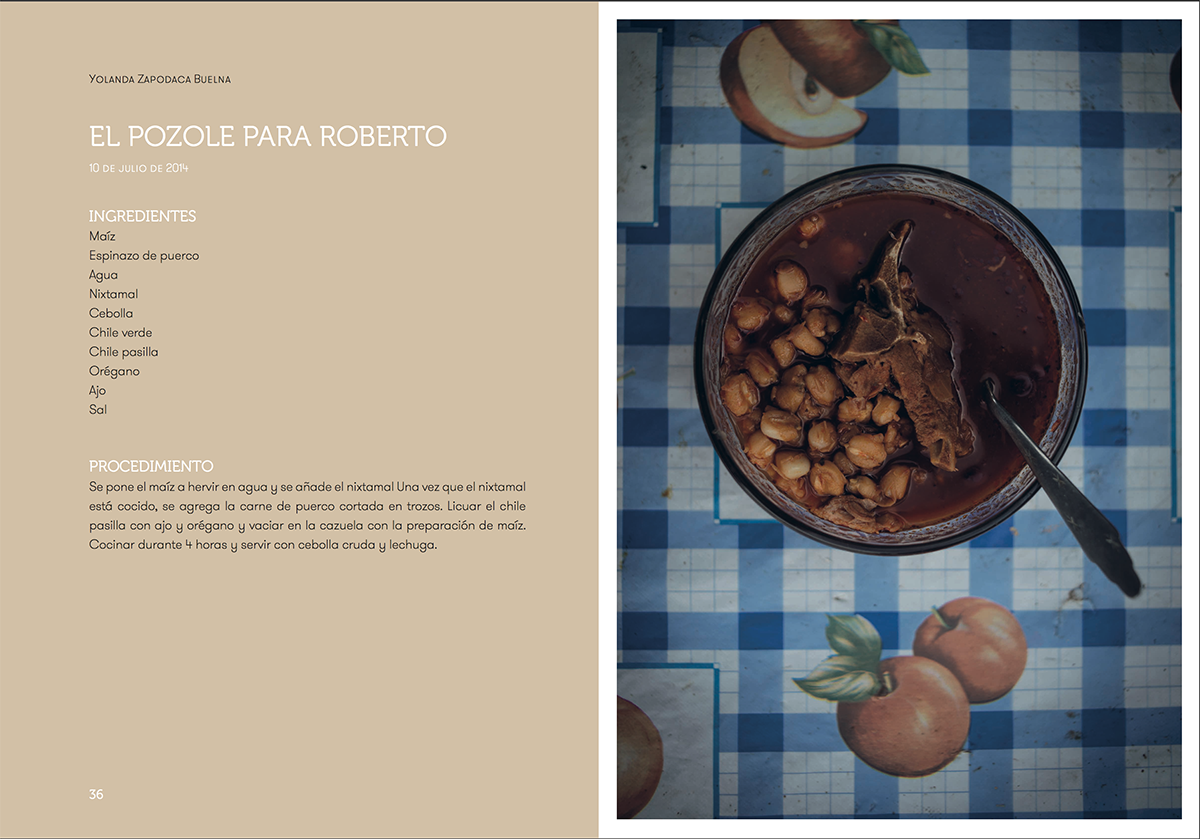

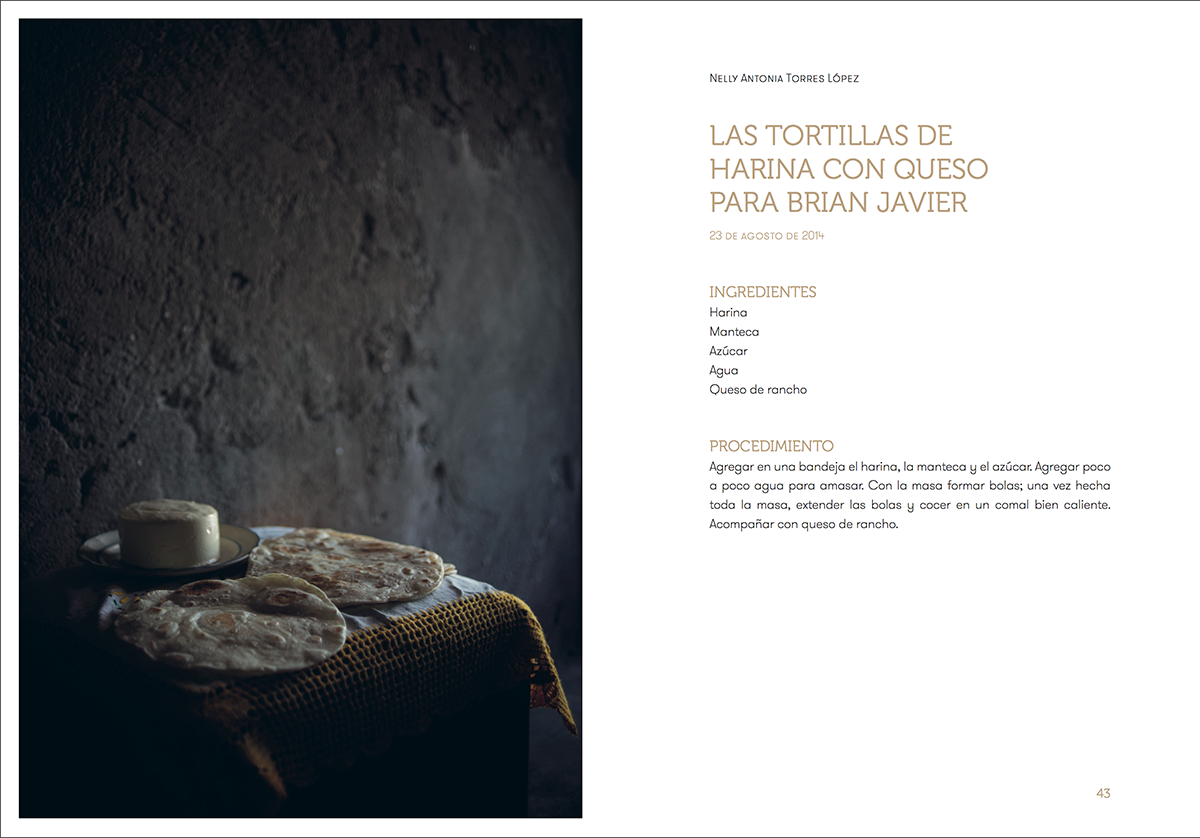

It’s called Recetario para la memoria (Recipe Book for Memory) and, there, the women shared the recipes for the ranchero steak that they made for Ernesto, the drowned shrimp for Susy, the goat’s head for Jorge Alberto, Sergio’s birria tacos and the pozole that Camilo loved, among several others.

How did the Cookbook for memory emerge and grow?

It comes as a chapter of a macro investigation that I have been working on for about 6 years. On a more personal level, my dad was Argentine. He left Argentina in 1978. The figure of the missing person is something I have been familiar with for a long time. In college I studied Art History. When I switched to photography, I really approached the forensic teams, the Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team (EAAF), the Colombian team, the Guatemalan team. I met “Las flores” in the Atacama desert, in Chile.

When I started working with that in Mexico, I faced that the urgency was different than in a country that looks back years. The Mexican forensic team is very recent, it is just taking shape, it was founded in 2014 and it still has little autonomy in the way it works. I had already met several groups of relatives. I took a trip there in 2017. We met some families, we hit it off. I did a very documentary or journalistic work on what are the traces, the graves, the office. After I was going several times a year, we began to have a strong relationship, the ladies and I. When I go I stay at their house. I began to ask myself a lot, in those comings and goings, what is it for? What does a photograph contribute to a debate on enforced disappearance with the urgency that Mexico has? I questioned the profession a lot.

I had an exhibition and there was something about always meeting them, which is wonderful but sometimes it jumps bridges. I lived it quite badly: who goes to museums? Who occupies the spaces? It is produced for an audience that is already alerted or already has a reflection on the subject. It made me very angry. I gave up personal photographic production a bit, I did keep going to Mochis, Sinaloa, to do registration support for them. I began to establish with them the desire, the desire: what most interested me was to do a collaborative or collective project but that was more hand in hand.

Also, with the challenge of removing this issue from circles where it is already being discussed. I was thinking about how to summon people who do not have that awareness so that they can be part of all this. In all these shared spaces, the idea of doing something collaboratively was forging, talking about the disappeared from a place that did not begin the moment they were taken away. Because, if not, it seems that the story started there. We wanted to go to other places that are also of life. It allows to give body to each and every one and not to remain in a figure.

Right now Mexico has 73,000 missing people. This figure is immeasurable, many things empty of meaning. In those shared spaces, other narratives also appeared: what Roberto was like, what Jean Paul liked… This is how the idea was built. In 2018 I proposed to the Rastreadoras: how if we make a cookbook?

The idea was that it could be used as a recipe book, that it was a way to bring the disappeared and be able to name them from other spaces. The sale goes fifty percent to them. The idea is that it allows them to keep walking. They are groups that are very lonely, that have no support. They go out to search on Wednesdays and Sundays. There is a tremendous struggle, which is sustained by sheer will, there is nothing else.

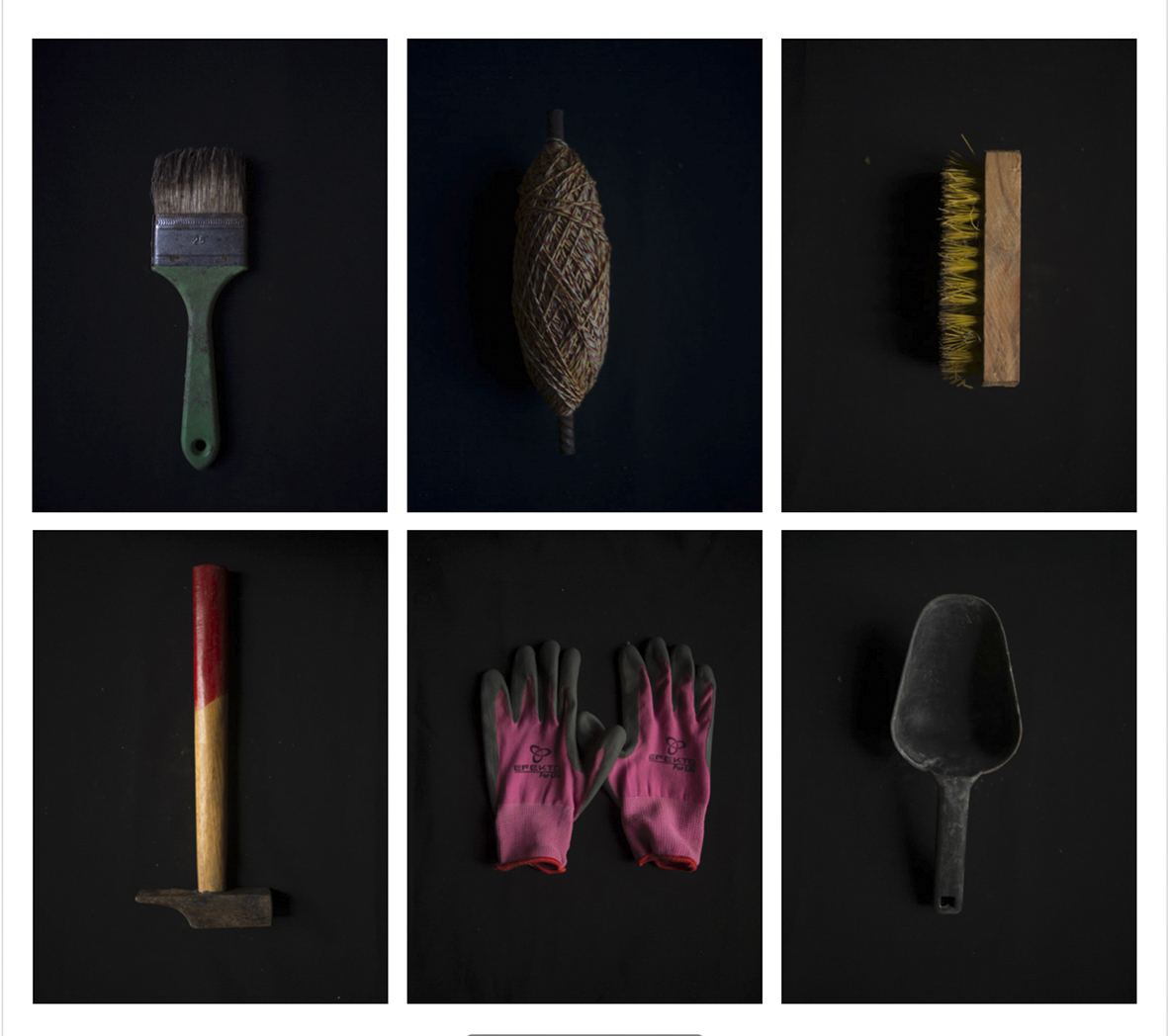

We started to work. I made a couple of attempts to see if it could work, see what could happen with a food photograph and how it could be handled with the recipes they have shared with me. That thing about when you call your aunt or your mom. She tells you the recipe but doesn’t tell you “it’s 100 grams.” There is a more spoken thing, something of the oral tradition.

How was the elaboration path?

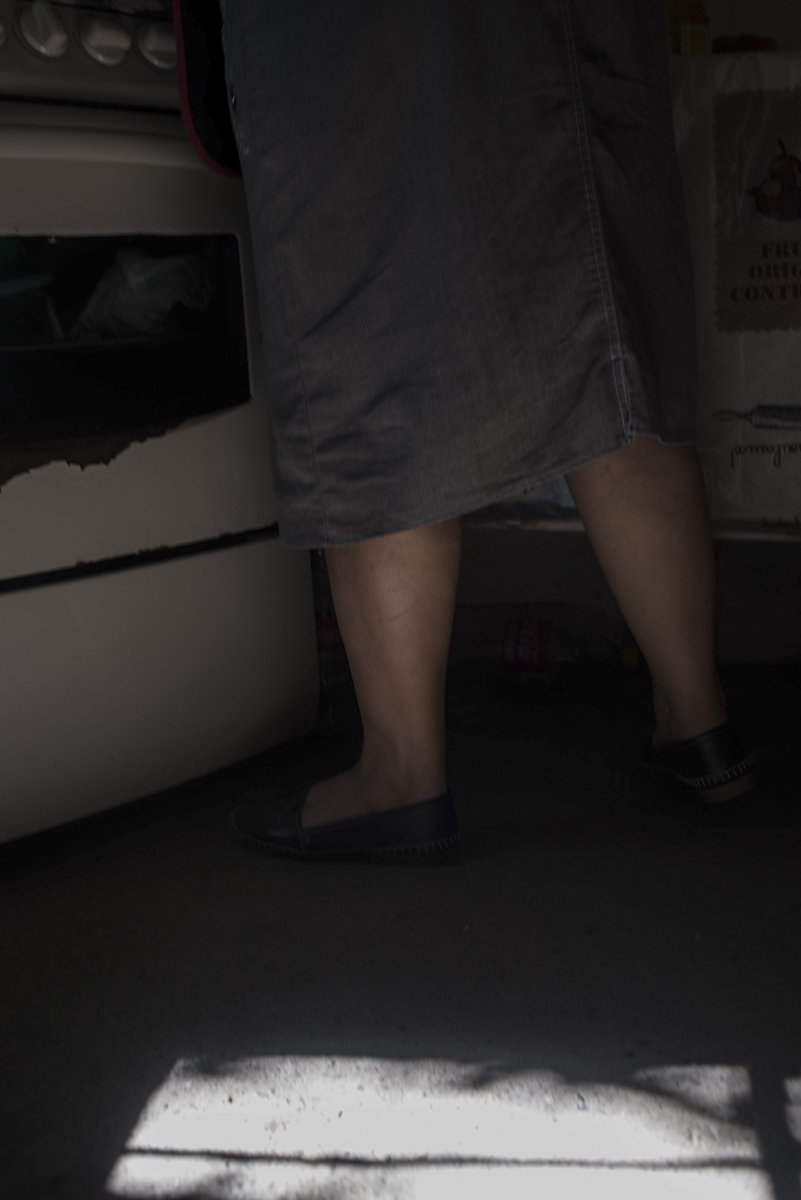

The investigation and registration process has been very generous on their part and at the same time, it has been very powerful: none of them had cooked that dish again since their son, brother, husband disappeared. The kitchen became a way of evoking the one they took and, at the same time, of sharing that non-presence from a very common act, which is the kitchen and a very everyday thing. All that process in the book does not appear and I think that it is the strongest thing.

They told me that cooking that dish that they had not cooked again was also an act, I don’t know if it was a cure, but it was an act of accompaniment, of making public a duel or a memory from a very intimate space. I became aware of all this as I worked with them. Being hungry is one of the most basic things. If you are not hungry, you are gone. To be hungry is to be alive. The relationship between mother and child is very strong in the sense of nutrition.

I asked Daniela Rea, María De Vecchi and Constanza Posadas (who writes for gastronomy) if they wanted to share a text. It is a project that, in all its steps, in the end has been extremely collaborative because Marisa Moura also joined, who did the design of the book and the girls who made the corrections (Tinta Roja editora).

What conclusion do you draw from collaborative work?

I think I will work more and more like this. There is a whole question about the photographed subject or the anthropological subject that I think should definitely be thrown away. In the same way that people who are not of the same profession summon other types of exercises. I have worked with human rights defenders, a hodgepodge of tools and knowledge that is built over time.

For example, Juan Orrantia and Mauricio Palos work on the traces of the Cold War in Latin America. We started working together with actors of the historical moment but also academics and activists. That created a discourse that is not unique, that is much more complex when it comes to what to do with it. Forensic anthropologists are mostly women, they get a space of a certain distance for the professional.

As communicators or journalists we always ask the same questions, so it always ends up being the same story. I do see that as problematic and we are responsible. It ends with a script of horror that I think needs to be broken. In that sense, the collaborative or the community does not allow you that, because you are in a constant dialogue and with a job where nothing is entirely up to you.

I think that the spaces in which a community is produced and when there is a direct deal, from you to you, does force you to rethink that. Speaking with the Trackers and with Mirna, the founder, in the end it is always the same story that repeats itself. You read one piece of news and you read the other and it is the same. So, I remember a conversation with Mirna that was: “What do you need?” Let’s see if I could contribute from my profession or not and that it was a joint construction. She told me that there was an economic need, which is almost a priority, so that they can continue searching for their “treasures”, that’s what they call their disappeared.

The issue is that the way of counting is cracking because nothing is flat or linear. It was changing in conversations with Daniela or in design. There is a loss of control that when we are used to working alone gives a bit of vertigo. And, at the same time, it enables other exchanges, other dialogues, opening up to other spaces.

I think you have to take part, get involved, perhaps from the tools of each one but not stand apart. It seems very dangerous to me. In political matters, obviously more, but I do believe that we can be stepping stones to communicate, lead elsewhere, find formats that can work. On the issue of enforced disappearance in Mexico, it really concerns us all. You cannot turn aside. You don’t have to have someone disappear to claim truth and justice. I think that is urgent. From the photographic and artist community, I believe that we also have to position ourselves as individuals.

How did you get to photography?

I always wanted to be a photographer, I say it in masculine. There was the whole mythology of the photographer, of a kind of errant knight who came with truth and justice, a war photographer and that kind of thing. I studied art history, I specialized in the history of photography. Right after I got out of college I worked at the Magnum agency and all my fantasies were taken out on me. It was a great school in many ways and it was also a tremendous “wow, I don’t know if I really want this” thing. I have had a link with photography for a long time.

Believing that “an image can change everything”, or that photography is “the purest thing”, you realize that it is a mythology. So you think: what happens now ?; What’s left? Well, photography is just photography. It is just a tool, nothing happens. It is not that serious and it is not that important. Yes, it is a useful tool. If what is best suited tomorrow is a projection, it will be a projection. If it is a paper print with letters, that will be it. Discard photography as the only medium. There is also, suddenly, to take food photography with a meaning. Culinary photography, within the documentary world at the level of myth, is not valued. But if that is what allows us to talk about this, it is incredible. Change functionality.

What changed between the book being an idea and becoming a reality?

The book is doing well, so they have had a lot of attention from very different people: it was Swedish television, the BBC, that for them is a great communication support on the struggle. And to create networks, make yourself heard. Each of those who participated has her book. The reception in all of them has been very incredible and very beautiful, they are very happy. As for participating, some said yes and then no; others said no and then yes; others did not speak. Right now many who did not want to do it. That is pretty.

She is Argentine-Spanish, with a Master’s degree in art history from the University of Paris Sorbonne. Now she lives in Mexico and collaborates with various publications such as Le Monde. The weekender, Vice, among others. She won awards and residencies (Wabi Sabi in Buenos Aires, PlatoHedro in Medellin, Field Days in Mexico, among others). She exhibited at the XVII Biennial of Photography at the Centro de la Imagen in Mexico City, at the Kaunas Photo Festival in Lithuania and at the Auckland Festival and the New Zealand Contemporary Art Festival, among other places.