Since Congress removed President Martín Vizcarra on November 9, Peru’s social and political crisis has been in the international news. The presidents resign, the streets fill up, the youth renew demands and forms, the police repress. After decades of disinterest, today mobilizations are once again perceived as the way to change the world.

Noelia Chávez graduated in sociology from the Universidad Católica del Perú. Now she analyzes the social and political phenomenon that Peru is going through with some hope. She argues that the neoliberal government of the 1990s had managed to depoliticize society and that, now, some of all that is changing. She observes that it is the youth who are leading the mobilizations and not so much the traditional organizations. But, in addition, that feminism modified the language with which to express oneself in the streets: colors appear, the most violent ways become translucent.

What did you find on the street?

In Lima, the first thing that impressed me was the crowded square, something I had never seen before, without posters that grouped the population, unions or traditional parties that were always what guided the marches. I’m someone who has participated in many marches for ten years but there is always coordination, respect for those who lead the mobilization, people who have experience. There was not that here, there were no flags that marked specific identities.

The second thing that caught my attention was that the mobilization was fragmented. It was moved by blocks. Suddenly, a group came out that was from a community and people did not follow it, they marched where they thought they had to go. There was no defined route, they did not all leave at the same time. That dismayed me because, at first, I said that the march had to have a movement to be powerful. I was thinking how tell people, “Please don’t separate.” But they were young people who were probably marching for the first time and I saw that everyone was going to take the monument. Then someone replied with the slogan to go to Congress and they began to move to the Judiciary. It was all very spontaneous. It was so big that it ended up occupying the entire center of Lima with different forms of mobilization. That seemed crazy to me.

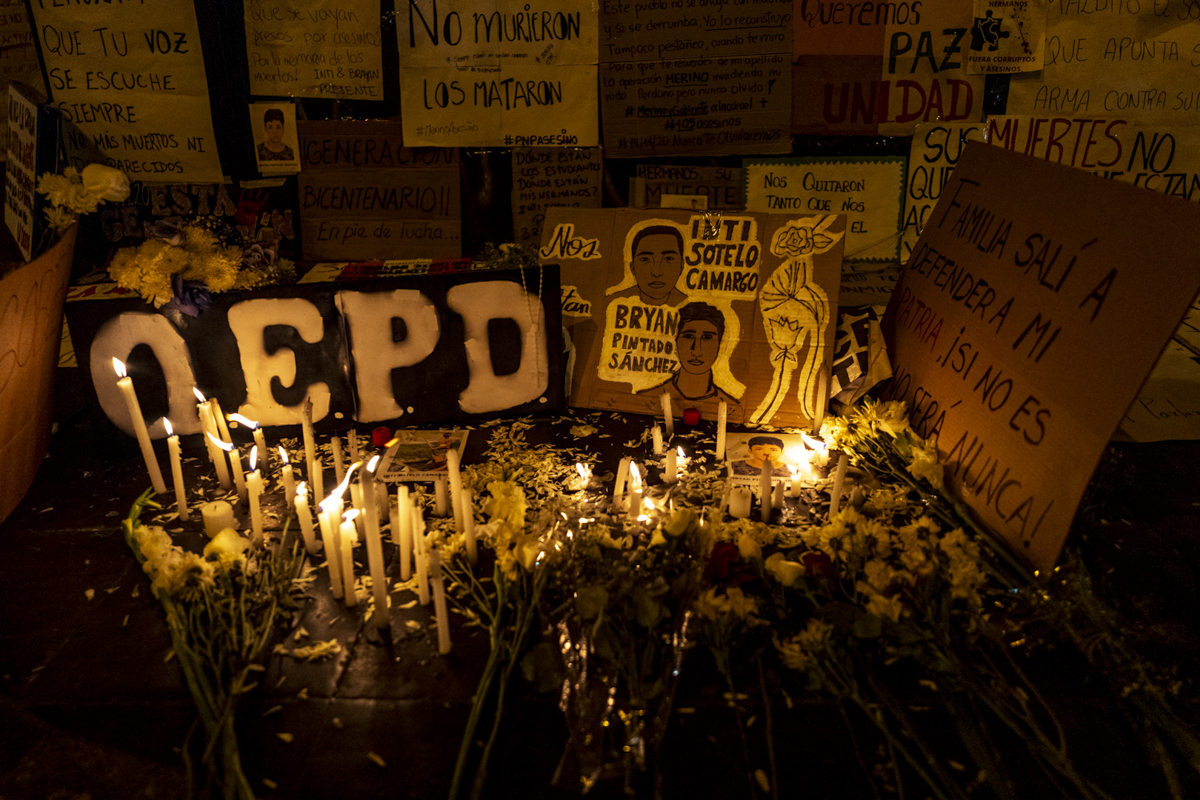

The third was the posters, made in their homes, not printed in one place. They were very colorful, humorous, burlesque phrases, using memes, gifs. I saw an “Elmo” costume, another one of Pikachu, or dinosaurs representing politicians. Before there were always some black birds from a theater agency that marched symbolizing death, those that eat carrion. But now they were not there, there were people disguised as rats, as pictures. I saw a performance that I had never seen before.

There were also the first aid brigades, medical students who organized to treat the wounded, which we already knew there would be. There were also the bomb deactivators, something that has been collected in former experiences in Chile. And they were not only men, there were also women. That’s something I’ve never seen in the country before and it’s mind-blowing.

The first line used to be the civil construction union and it was the one that was going to clash with the police. This time it was not them, they were fans of teams united in the strike force, on the front line. There was an experience in 2015 against the labor regime and there were mobilizations with new identities. I think that was a seed for what has happened now.

What do you identify again in this phenomenon?

We are a country with a very strong apolitical culture that dates back to the 80s and 90s due to the internal armed conflict and the terrorist group Sendero Luminoso, which ended up making the political class that was born in the 90s very neoliberal and conservative. They took power to stabilize the country and were generating an apolitization of the people, stigmatizing the left as radical and the citizen protest as terrorist. That is a weight we carry for a long time.

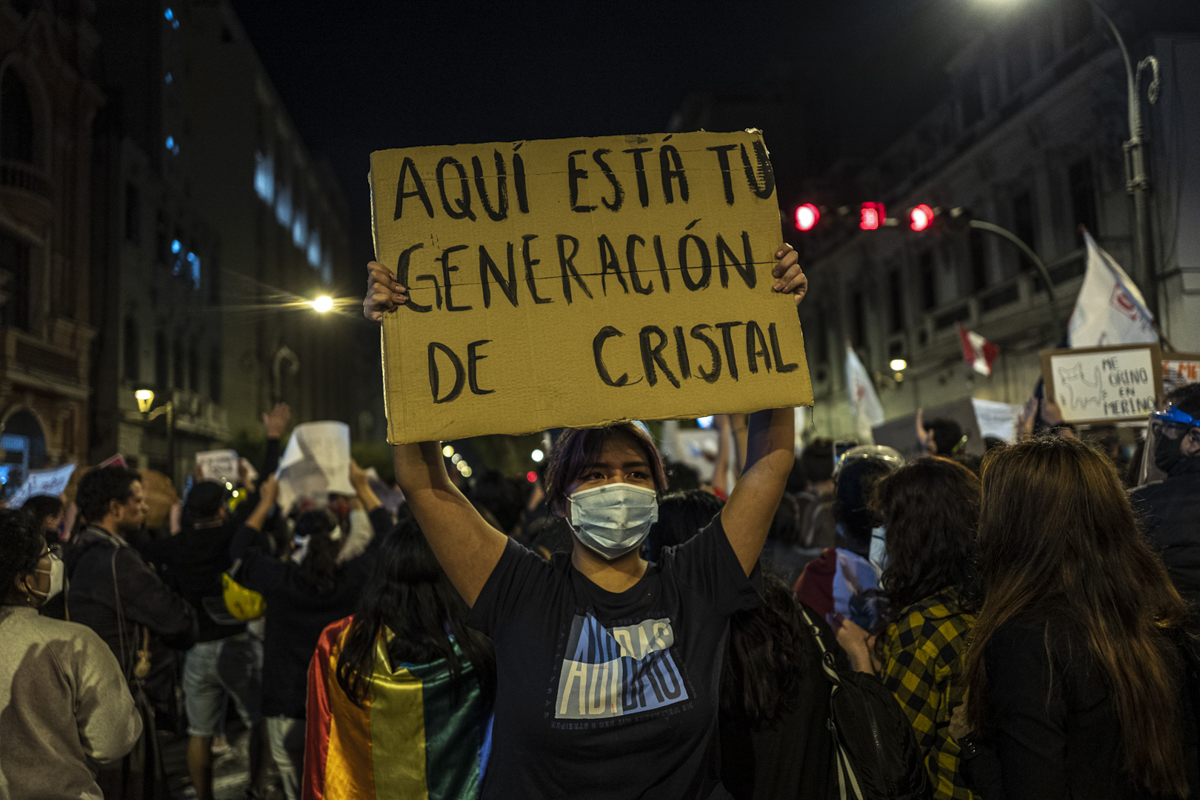

But I believe that this new youth, which was born in a democracy, in the 2000s, in an economic pole, do not know those ghosts, they have not lived them. We can see a break in our political culture: from an apolitization in the 90s, when we have had one automatic pilot in our country, a citizenry that detaches itself from those ghosts that we have in the past to be able to dress or clothe our social manifestation of a citizen act. It is a Peruvian process, different from Chile, where human rights have been violated since the right-wing dictatorship of [Augusto] Pinochet. Here, on the other hand, the problem was a terrorist group that considered itself communist and radical on the left. That cheated on our left and so far it’s hard for the left to recover. Anything that implied dispute was dyed “radical and earthy.” We have managed to make fun of this “terrorist-protests” thing. Now it is, rather, “citizen-protests”. It is important to achieve change. That helps to think about it.

In fact, the process took a long time and that starts a cycle of crisis and permanent confrontation between the powers. That led to what we have right now: three presidents in a week, giant social protests, but it is part of a transition process that we are experiencing. The last was in 2000, but from then on our democracy was weak and these last four or five years have ended up being a time bomb that was going to explode at some point. It has exploded now.

Do you feel that Peru sounds to the rhythm of Latin America?

There is a music of change. In Peru it has always been believed that we are “behind” with the waves of political and ideological changes of the right and left. I believe that each country has its processes and we are still in the same cycle, of much demand and of much realization that the “growth” that we have had in recent years in South America has not really ended up benefiting citizens. I have the impression that there is a discomfort for a greater citizen need than we have only for having economic resources. At least, in Peru, I feel that way. And I think that in Chile too: a stable nation, economically prosperous but with an important citizen demand for social change that is required, there is a divorce there.

What do you observe in the youth?

I think we are talking about subjects, in the plural, because what I see in the youth is that they are not labeled under the traditional actors that have led protests, at least in Peru. I think it has a lot of diversity. In Peru, what had happened is a demonstration of a scheme of citizen organization. The labor union, guild and civil organizations with more trajectory and weight are not heading the social outbreak. Also, had left in some cases, to represent the big diversity in the identities that we have in our countries. There is a great diversity in cultural identities, political identities, citizen demands and several realities.

It gives me the impression that this inequality in our countries, mixed with the privileges that give us economic growth, ends up multiplying the citizen interest in a bigger way. So, Peru have the Lima people: young people of private universities that do not necessarily march/protest as students and reclaim a major political stability, that do not usurp them democracy. But, there are also tiktokers from the rural area of the country, the indigenous communities, that raise their voices and say:”this is a fight between the powerfuls, do not include us in it”. That is another narrative.

I feel there is something that characterizes this youth, it is much more diverse than some previous youths that had been struggling with the elites who do not represent them but they had more compacted identities. They were “the” students of Perú, for example, in the years of dictatorship. THey were organized under the student identity, and did not march in the city.

I’m also thinking of the young university students of the 1920s who spread throughout South America, who were young intellectual elites who ended up facing older elites. Also, in the 70s the labor union ended mobilizing the population as the worker class. What we see now is a diversity of identities and is polyclassist: the youth of Lima from public universities, someones that have to leave the universities or study in cheap and low quality universities. And everyone represented themselves or a little group. I think there are a lot of politics groups and we will have to see where they go.

And where do you think it is going?

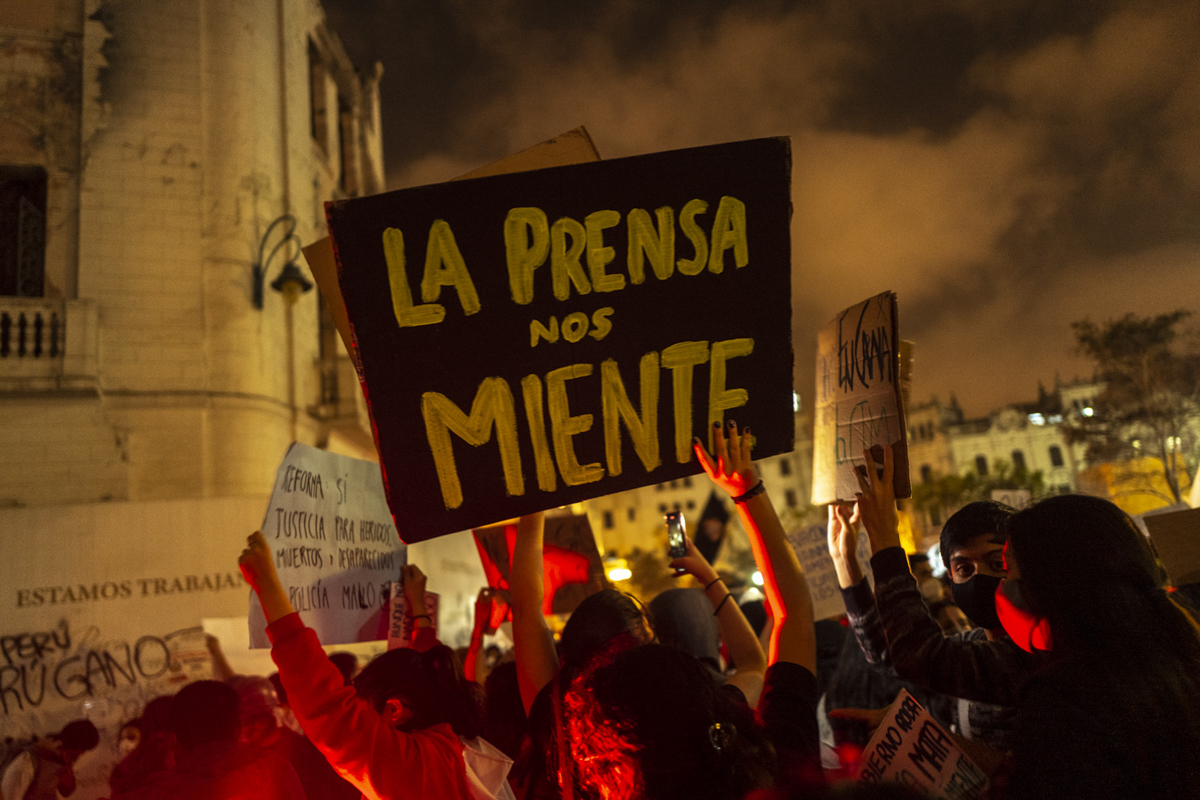

In Peru there is no politically clear project towards which we want to advance. As in Chile, where perhaps the public discussion was much more mature and will end up favoring a new Constitution. In Peru, what you have is a satiety that erupts in a social protest that learns from previous social protests but that grows larger and that is built from some forward political projects. The Constituent Assembly is one of them but it is still under construction; the Police Reform is another; the discourse against the media, but it is not yet forged. It is to claim, raise your voice, not remain silent, they are not going to remain silent in front of an older generation, to that position of should be, perhaps.

Before the “politic subject”, the stereotype of whoever protested was a young man, student or syndicalist. Instead, what we have now as the profile in Peru is a woman. The average of those who protested is the figure of middle class women, from 18 to 24 years old, that have a lot of interest in politics. Three of four are interested in politics but they do not feel represented by any political party or collective of ideology. That is interesting because it changes our way of seeing the protest and how the feminist movement has penetrated very deeply over these years.

We are not futurologists and we don’t know what is going to happen. For what I see is an effervescence of interest in politics by the young people that have protested. Is what the statistics says. Probably it has been the most massive of our history: the 37 percent of the population considered that, in some way, had participated in the protest. Is a lot, more than the third part.

This interest translates into a participation in virtual space and physical space, there is a great capacity for rapid articulation. What I feel is that there is a culture that is being formed of supervision of public authorities: what do our leaders do? What do our institutions do? This oversight of politics is going to continue, I get the impression. Faced with any action that may violate identities, rights or everything that young people consider important to safeguard their freedoms and desires, they will re-articulate, go out.

What is not clear to me is whether this will lead to political identities that allow us to really generate a change in our political class, which is ultimately the one we are up against. I believe, and sociologist Omar Coronel has already said, that there is a politicization but it seems that there is a rejection of the partisan. In a democracy, parties are the vehicle of political representation to reach public office. So, if politicization does not find channels or bridges with institutional politics, it will be difficult to change that political class and we will always be a country reactive to that political class. It is not clear to me how we are going to get there. Hopefully this diversity will lead us to build a diversity of political projects that can reach different audiences, but that is still evolving.

How did feminism go through these mobilizations?

We know that the feminist movement is historical but I think that in this time it has become a collective movement. What’s more, they say collective. They made visible very big structural problems that exist in our country regarding violence against women and sexual minorities, LGTBI as well. They have begun to move progressive values in a very traditional society. Peru, Lima, is probably one of the most traditional and conservative places in Latin America. The feminist and LGTBI movement moves a series of progressive agendas on equal rights. I think that is beginning to permeate the minds of individualities, in a very individualized, capitalist world. Those identities want to be recognized, they want to be not hidden, not homogenized. They don’t want a way to be imposed.

There have been emblematic cases of violence in the country, of very strong femicides. There are also painful statistics on sexual violence, even within the family. It is the country with the highest rate of family sexual violence. These images have made feminism become very powerful and this has politicized women a lot, who no longer remain silent and now speak. This has been a key piece in forming a mobilizable, mobilized identity that at a moment of juncture where they are robbing you of the little bit of democracy that you have, you also go out to march. That is a different mobilization because it takes out a toxic masculinity that social mobilization had, of being violent, aggressive, linked to that traditional masculinity where mobilization is confrontation. It is going towards a different mobilization: colorful and with many characteristics that are disruptive with the masculine.

In many respects, the crisis of the old mandates and old forms of resistance appear to be in crisis.

I feel that due to the hyperconnectivity that we have, these processes are faster. The space-time of the mandates is shortened. Throughout the history of the twentieth century to this part the confrontation between youth and adults has existed. If you think of Woodstock in the 60s, you see young people revealing themselves to ways of being and doing. It is a struggle for power, finally, where an older generation has slogans, ways of doing things, a scheme and structure on how the internalized and repeated world works. That allows a series of stabilities that is not bad either. But it is a structure that is imposed on those who are searching for their own identities. That is where, I believe, the confrontation between the youth, which seeks power, and an older generation, which seeks to impose a way of doing things, is born.

Not everything is so homogeneous, there are older people in Lima who join the protests led by young people. There are fathers, mothers, adults who have seen the potential for change and go out to pan, things that I have never seen in my country. But I think this has always existed and now it is faster and stronger because of our ability to say things, to go viral and get people together. It is done instantly. We have people who are speakers, people listened to by millions of people. A political party cannot do that, they are not heard that way, but a tiktoker, yes. That is interesting and has its risks, but I think there is a speed that makes it less able to contain emotionality and mobilization.