When Susana Vargas went to meet Juana Barrasa, named by the press as Mataviejitas (the little old lady killer), she was surprised by the sweetness of her voice, the pretty smile with the small teeth and the electric blue eyeliner. Somehow she felt identified: she herself had been told that there was a strange effect when hearing her speak in a very sweet voice on topics related to various forms of violence.

Susana Vargas is a Mexican writer, researcher and teacher. Her works investigate the connections between gender, sexuality, class and skin tones in order to consider the notion of pigmentocracy as a social system that does not necessarily have to do with skin tone, but with the way it is perceived and defined by social class and gender.

“A white person is not read white just because of its skin pigment,” says Susana, “but because of all the social attributes that accompany it that are inseparable. It’s not like you can put it on or take off the class. It is not a Gucci bag that you take it off and that’s it. It’s how you speak, it’s how you embody yourself”.

All this is articulated to the study of subjectivity, to the way in which we constitute ourselves as subjects, because according to her, “there is so important the sex-gender identification as of class and skin tone”. To understand it, Susana uses the concept of performativity, built from several theories by Judith Butler for gender studies, with which she can understand sex and gender, but also race, from the idea of something that is done in constant repetition and that is embodied in a series of actions that are based on a bodily materiality but whose readings and interpretations are social. From there she raises her studies and positions photography as a medium that allows her to understand this construction of subjectivity in the Mexican context. With this perspective, Susana has carried out research that has become the books: Mujercitos (Little Women) (published by RM in 2015) and The Little Old Lady Killer. The Sensationalized Crimes of Mexico’s First Female Serial Killer (published last year).

A few weeks ago Susana Vargas participated as a guest in the live of Cristina’s Monday on instagram, talking with Cristina de Middel. At the event, she spoke of a position that defines her intellectual work and that consists of having a gender consciousness, a feminist consciousness. She understands feminism as “the critical and analytical method of the practice of self-awareness”, following the definition of Teresa de Lauretis in her book Technologies of gender. This could be translated knowing: “who are you, where are you and what is your position as a subject”, that is, according to Marika Combativa, a gender and human rights promoter from Argentina whom Susana mentioned in that live, is to know and understand who you have next and who you have above.

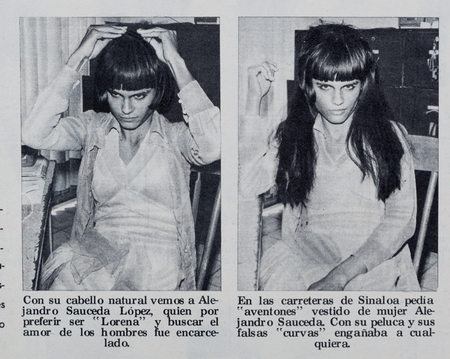

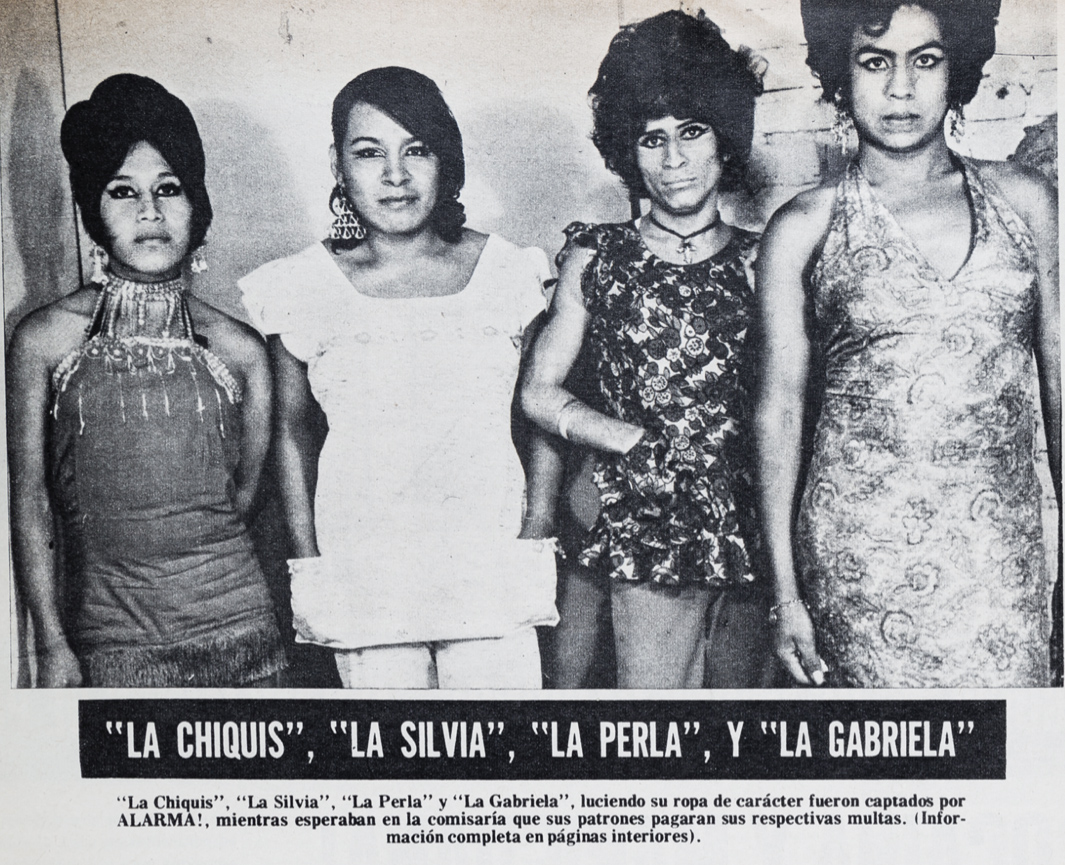

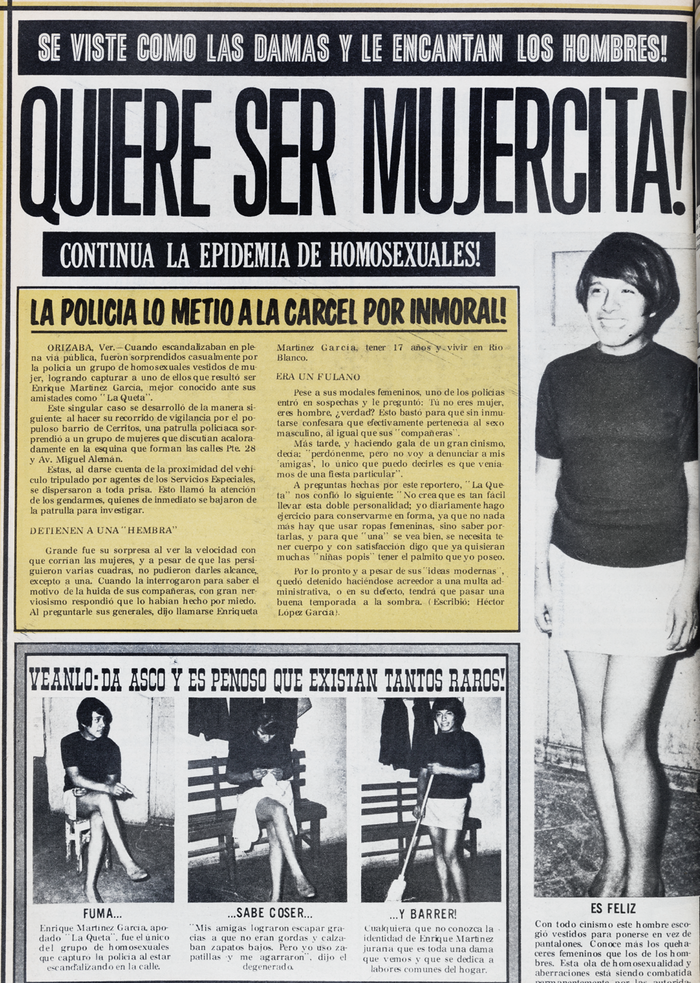

In addition to having a feminist conscience, for Susana it is crucial to “pull up, towards the system and the structure”, because by doing the opposite “you would be oppressing and exercising symbolic violence”. Positioned in this way, in 2015 she published Mujercitos. The research on which the book is based was her doctoral thesis. She started with an archival job reviewing copies of Alarma! a Mexican newspaper of nota roja published between 1963 and 1986. The nota roja, elsewhere called the yellow journalism, is a style of journalism characterized by the explicit photographic content of violent crimes. She analyzed the photographs of the mujercitos, “effeminate men,” as they were called in the newspaper. Many of the photographs were taken in police raids at clandestine parties, or in police stations where they were transferred.

Mujercitos was the derogatory nickname that trans women received at that time in the Alarma! Susana clarifies in the introductory text of the book that she did not refer to them as trans women because, in the first place, it was not a common way to name themselves in the period in which the photos were taken (1963-1986), and secondly, because it is an appellation of Anglo-Saxon origin that little by little has been appropriated. At the time in Mexico, they recognized themselves as transvestites.

Photography has the power to fix ideas and images. “What seemed interesting to me was that the image of a little woman posing and not the image of a shotgunned woman remained fixed for more than twenty-three consecutive years,” says Susana. The most portrayed reality is the second, but in Alarma! the images that appeared were those of them posing and showing their femininity. Roshell Terranova, a famous Mexican artist, participated as a special guest at the launch of the book in Mexico, who told how for her as a trans woman the newspaper Alarma! had been el coco (boogie monster), the publication where “the worst that could exist in society” appeared. With Susana’s work, she was surprised to see that the photos of the Mujercitos said different things.

It is not possible to know to what extent the photographer had some complicity with them, if he asked them to pose, or if they were the ones who decided. And yet the important thing here is to see the end result. Without a doubt, Susana affirms, what there is is a tension between the punishment of homoerotic desire, which at the same time is liberated in the way the photos were taken.

The intention when doing the research and the book was “to go back, give it importance and re-dignify that it was the Mujercitos who took that space and made it their own.” For the author, the little women exerted resistance by using photography as a space to show their feminine subjectivity. The same for which they were discriminated against and stigmatized. And this, says Susana, allows us to see how the relationship between photographer and photographed does not necessarily occur in a single way, it is not only a relationship between an active subject (the photographer) and a passive one (the photographed). At least in this case, she identifies an act of resistance that occurs at the moment in which these dynamics, which could be called traditional, are altered and the power relationship that underlies them is subverted.

Both this book and The little old lady killer seek to contextualize theories about gender performativity in a Mexican context, which could also be extended to a Latin American one. For her, gender performativity is not a concept that can be applied to a certain investigation and not to another, nor is it a methodology of observation: it is a way of understanding the world and assuming it. It is the way of becoming a subject.

This perspective tries to move away from thinking about gender as biological essentialism, that is, women are feminine and men are masculine by nature; or solely as a social construction, in which somehow it is assumed that gender is something that can be chosen voluntarily.

Susana explains it like this: “it’s not that you decide what gender you are going to be this morning, but that you are made up of the gender that you were assigned at birth. And this gender works as a series of repeated and stylized acts that you cannot really escape, that is, you can exert short resistances in certain movements; but the gender is not necessarily subverted, it is not a choice. Performativity implies thinking about it from a series of stylized acts. It is not an individual decision, but a larger system, thanks to which we have come to associate that pink is a girl. ”

The example that she gives is that of the gender reveal parties that have recently gained a lot of strength and in which the pink- female, blue-male association registers again. The strength of this performativity is in repetition, in doing it over and over again. At these parties, the most shocking thing is that this gender is being defined even when the baby has not been born, but a series of attributes are already being assigned to it.

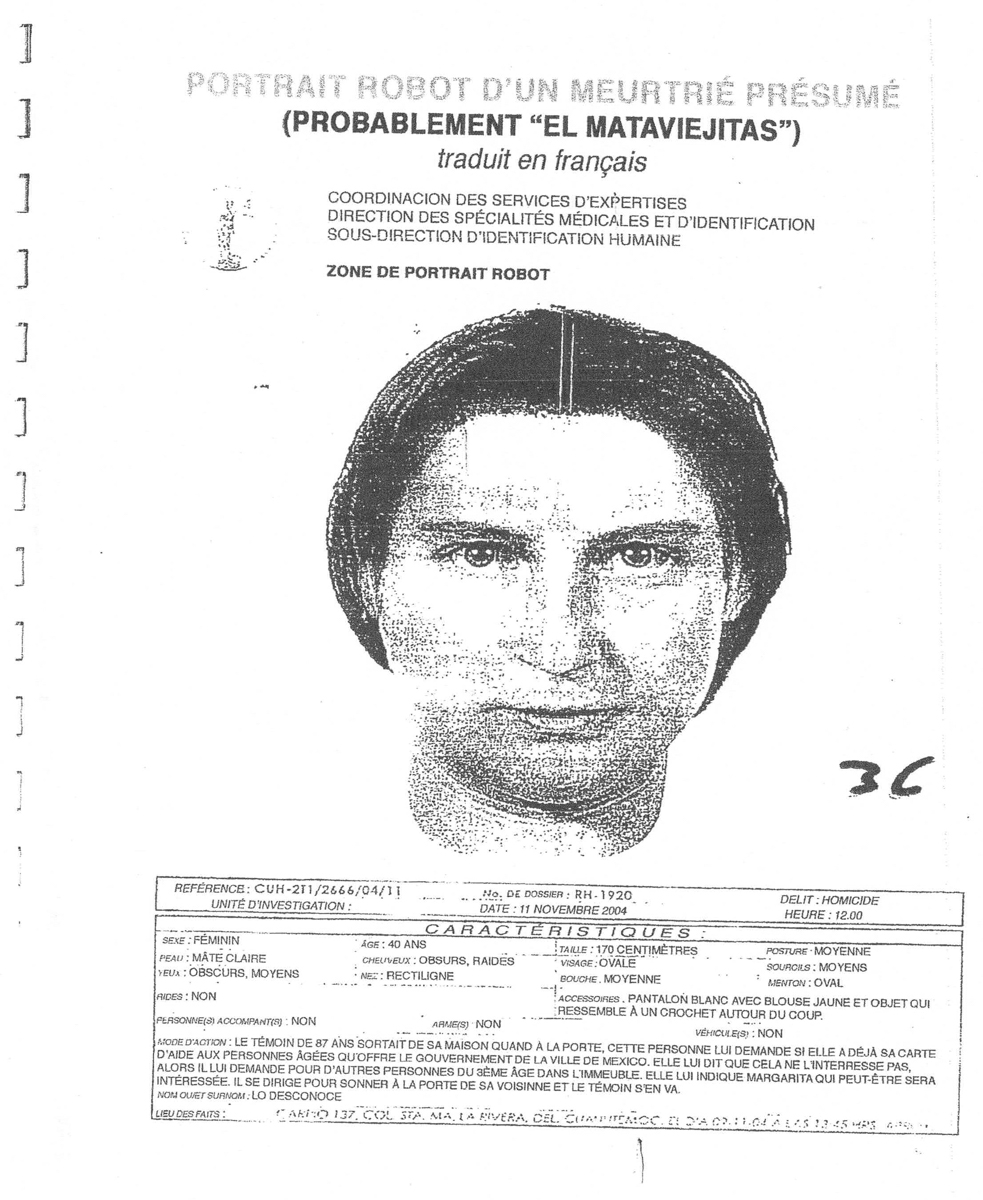

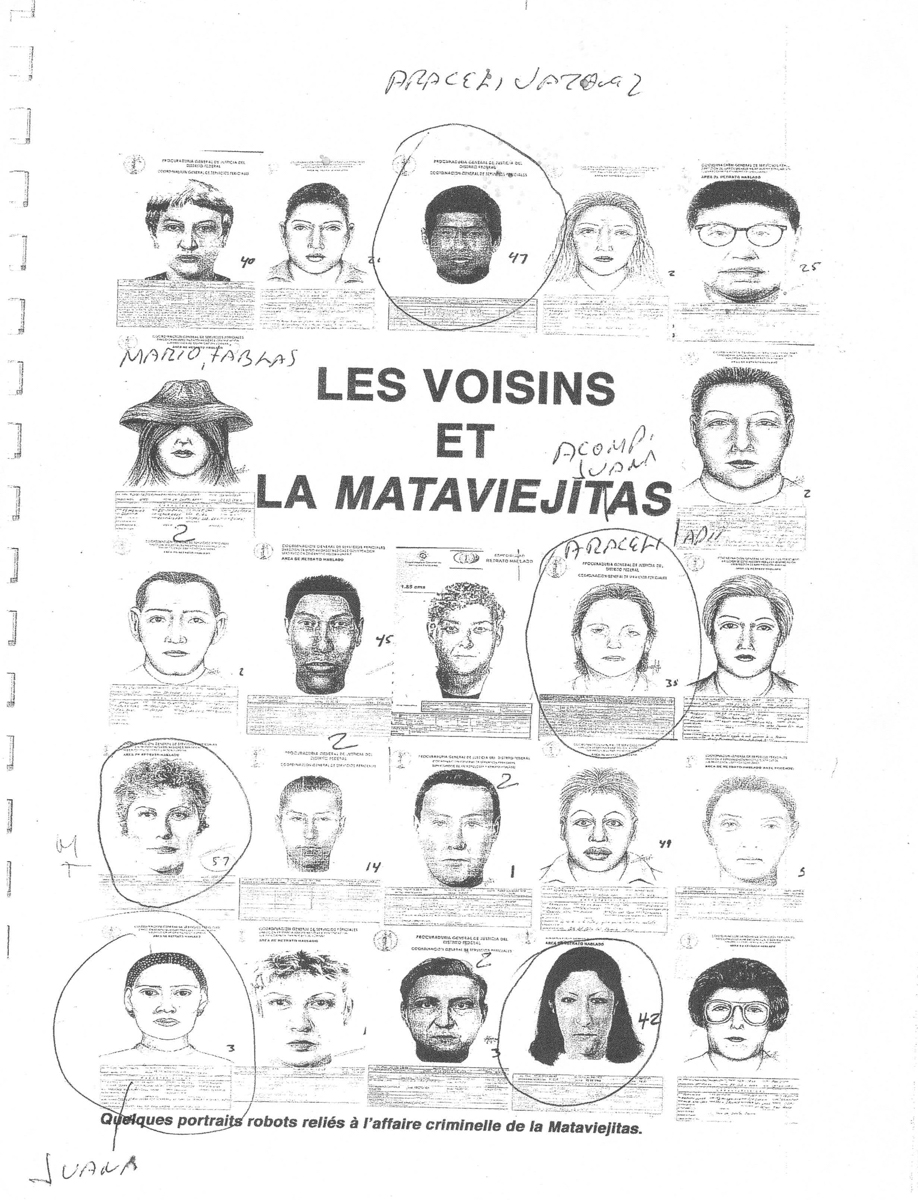

The gender assigned at birth is embodied and performed in those acts that Susana speaks of. It is made up of a series of socially assigned and constructed attributes. One of them indicates that women, for example, are not violent. In The little old lady killer Susana studies the case of a woman declared the first serial murderer in Mexico. She analyzed police reports and press speeches in relation to international criminal speeches and Mexican popular culture, in addition to the portraits constructed by police investigators.

They called her Mataviejitas (little old lady killer) because the crimes, committed between the late 1990s and early 2006, coincided with the violent death of women in their 70s, all of whom were strangled. At first it was thought that she was a man; later, by descriptions of witnesses who spoke of a tall, muscular person, apparently with a wig and women’s clothes, they thought that it was a transvestite. In October 2005, they arrested a number of transvestite sex workers and, since none of them matched their fingerprints, they concluded that it was probably not a transvestite, but it certainly must be a trans person. They never imagined that it could be a woman.

Susana says that: “the interesting thing was that they used computer sketches from photographs of what they consider to be the average mestizo in Mexico and these sketches were just like Juana Barrasa, who was later declared the Mataviejitas. To the point where officials said they recognized her immediately from the skits. When it was pure luck that they found her. ”

In other words: it is assumed that these search images of criminals are made following objective procedures. However, these photographs and images and their interpretations are traversed by international narratives of serial killers that, the author explains: “are re-inscribed from many films and series. And because it’s a US phenomenon, serial killers are thought to be exclusively male, white, American, and highly intelligent. ”

In addition, a violent woman “goes beyond all the canons of feminine normativity, it is something almost impossible to think.” The images and the narratives associated with them were all tied to a way of understanding the world in which it is not possible for a woman to be a murderer, less than that level. The portraits also reproduced the idea that the suspect was a half-Mexican mestizo, not a white person (in that context, possibly upper-class). The construction of subjectivity and gender performativity are traversed by these narratives as well.

The problem and what draws Susana’s attention is that “in photography and especially in photography for criminal identification purposes there is the belief that it is totally objective and true when there are also all these prejudices and interpretations.” Obviously the images are not isolated events, they are crossed by discourses and narratives, they are part of sociocultural systems and are made by subjects in specific historical contexts. The charge of truth that is expected and required of photography implies a different relationship with it than with other types of images. Speaking with Cristina, Susana recalled Susan Sontag in her two books On Photography and Regarding the Pain of Others, the author establishes a suspicion of photography as a medium because “on the one hand she demands the truth, and on the other hand she knows that it can never give us the whole truth.” Of course, this is required both of the images and of the creators, Susana points out how this is also the responsibility of the viewers.

These two books by Susana can be read as an invitation to think about how images are constructed and interpreted, and how they are part of the ways in which we constitute ourselves as subjects in specific social systems. Reading and creating images requires reflection that calls into question the burden of truth that is given to photographs, but also helps us understand how they are being part of our personal construction. In that sense, it is interesting to see how somehow a newspaper of yellow journalism like Alarma! generated a collection of images that appeared in the midst of discrimination and violence, but that leave the message of people participating in the creation of images of themselves loaded with strength and dignity. And also, how the fact that Mataviejitas was a woman casts doubt on the objectivity of the creation of photographs for criminal identification purposes. In both cases, in addition, the research carried out by Susana shows the richness and power that an image analysis work can have to understand the societies in which we live and thus be able to do what she proposes with the “feminist conscience”.