“I am an artisan of photography”, tells Alexandra McNichols-Torroledo. Every person who knows her work will agree with this definition. This does not imply that this Colombian-American photographer has given up technology and digital process. Instead, it suppose some kind of fascination for chemistry, labs, textures of the paper and the photographic processing. She is in love with the technique.

How to count violence without this being the only thing that is told about a territory. That is what the dilemma you face when telling is about. In her photos, the artistic meets the documentary and her training as a communicator was key to sharpening the eye. Perhaps that is why the issues she focuses on have to do with social problems in Latin America and the multiple types of violence that lie behind.

Today, Alexandra lives in the United States and gives some workshops of the platinum-palladium photographic process, which, in her words, is “one of the analogic processes more exquisite in photography”. Her work had been published in media such as El espectador from Colombia and The Guardian from the United Kingdom. Her work was exhibited in the United States, Colombia and Dominican Republic.

Together with the artist Estefanía García Pineda, Alexandra is developening a project commissioned by Visit. To the documentary work that he did with the platinum-palladium technique in the Kitek Kiwe reservation, one of the Nasa communities of the Cauca region displaced by paramilitaries in 2001, they will add a handcrafted print co-authored with them: they will print the photos on paper of Coca leaf. They will make it in a workshop in the same community, with the protagonists of the images.

Why did you decide to study analog processes in a world that tends to be increasingly digital?

When I went to university there were no computers. The most beautiful things I saw in those four years in which I studied Social Communication and Journalism were two things: first, the photography lab, and I fell in love. Secondly, I was incredibly lucky because Mauricio Cruz, a great curator of the time, came to university and instead of graduating with a journalism thesis, I graduated with an installation, with a science fiction thesis, really nothing journalistic. I come from a school in which I had a great artistic teaching of social communication.

Today, although I do digital and take advantage of the benefits of digital, my love and strength is artisanal. I love being in the photo lab: the texture of the paper, having to add chemicals. When I see images of people with whom I apply for scholarships, I discover that I am an artisan of photography.

I have a love for the platinum-palladium process: it is an exquisite process, which I have also taught in Colombia and in the United States. It is something that is disappearing as most people went digital, without a photo lab. When I travel I go to the territories with old cameras and also digital cameras. My base is the old 4×5 plate camera.

You worked with this combination between the analog and digital camera and found different senses in taking images with each of those cameras. What are those differences like and how were they expressed in that particular work?

I take some shots to make the negatives with the plate camera, which is from 1938 and others with the cell phone. Sometimes it is a little maddening but it is very interesting because I have been working on the beauty of the process and each format tells us about a different story. The plate tells us about the past and has another time. Color tells us about the moment. I like to collect everything.

In a way, with the 4×5 camera I am limited to portraits. That is why you see in my photography that there is a lot of portraits, sometimes modern. I also make use of combining elements from each community. The 4×5 camera is a camera that allows me to enjoy the act of being a photographer more because i make thoughtful photos with it. Sometimes I take photos that are not posed at all. But I am there long time, I do not go with the speed of digital because the plate is expensive, it takes me time to develop the negatives. First I think about what I want from the photo, I work with more of a photographer’s eye.

The 4×5 camera allows me to discuss more, talk more with people and the digital camera allows me to be more agile, capturing scenes in which due to the light conditions I could not have again and moments in which I have to take out quickly

How do you work with the platinum-palladium process?

To copy I use a formula that allows me to work with digital or analog negative. You work in the dark room. I put three droplets on the paper, they are processes that have to be done carefully. The preparation looks like brandy. With the size of the negative marked, I turn the preparation over on the paper and with the glass rod I spread the metals. Then I put it to dry and put the negative on a glass. I carry it on glass in a dark bag and expose it to the sun. Then I put it on a tray and add a developer. The photo is instantly like this and will not change. After removing it from the developer -with gloves due to the chemical- it goes to a tray where there is a cleaning agent and I do a gentle wash with water for 30 minutes.

In the pandemic I taught this process virtually the first time. I had a commitment in Colombia to teach it at a festival and in the end it was carried out virtually. It was a very nice challenge to do it. Those are incredible processes.

Where does that love for analog photography come from?

My love with photography started when, for the first time, I saw photography classes in my communication studies. I’m from Bogotá, and at that time I had one or two photography classes. Then I went backpacking to Europe and when I came here and they gave me a doctorate scholarship in 2008, I got into photography. With the scholarship I went to the United States where I studied all analog processes. In my three or four years of experimentation I worked with all kinds of cameras and developed and learned all these photographic processes that I use today. My photography is between analog and digital.

Tell us about the project that can be seen on the Drogas, Políticas y Violencias platform.

I have been working since 2011 with indigenous communities in Colombia that have been suffering severely in relation to the problems of displacement and the coca leaf business. It was necessary to raise the problem of the war on cocaine and coca.

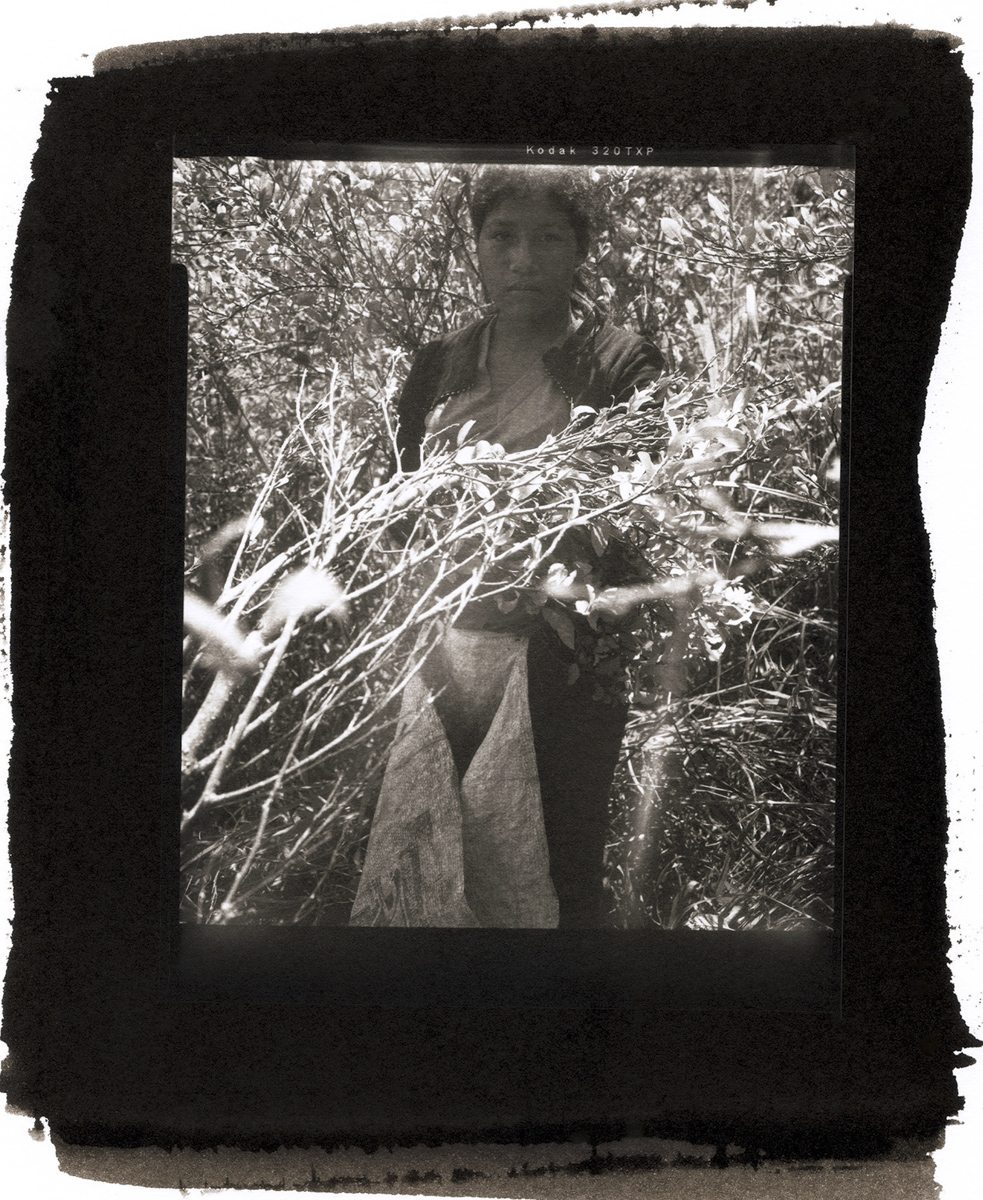

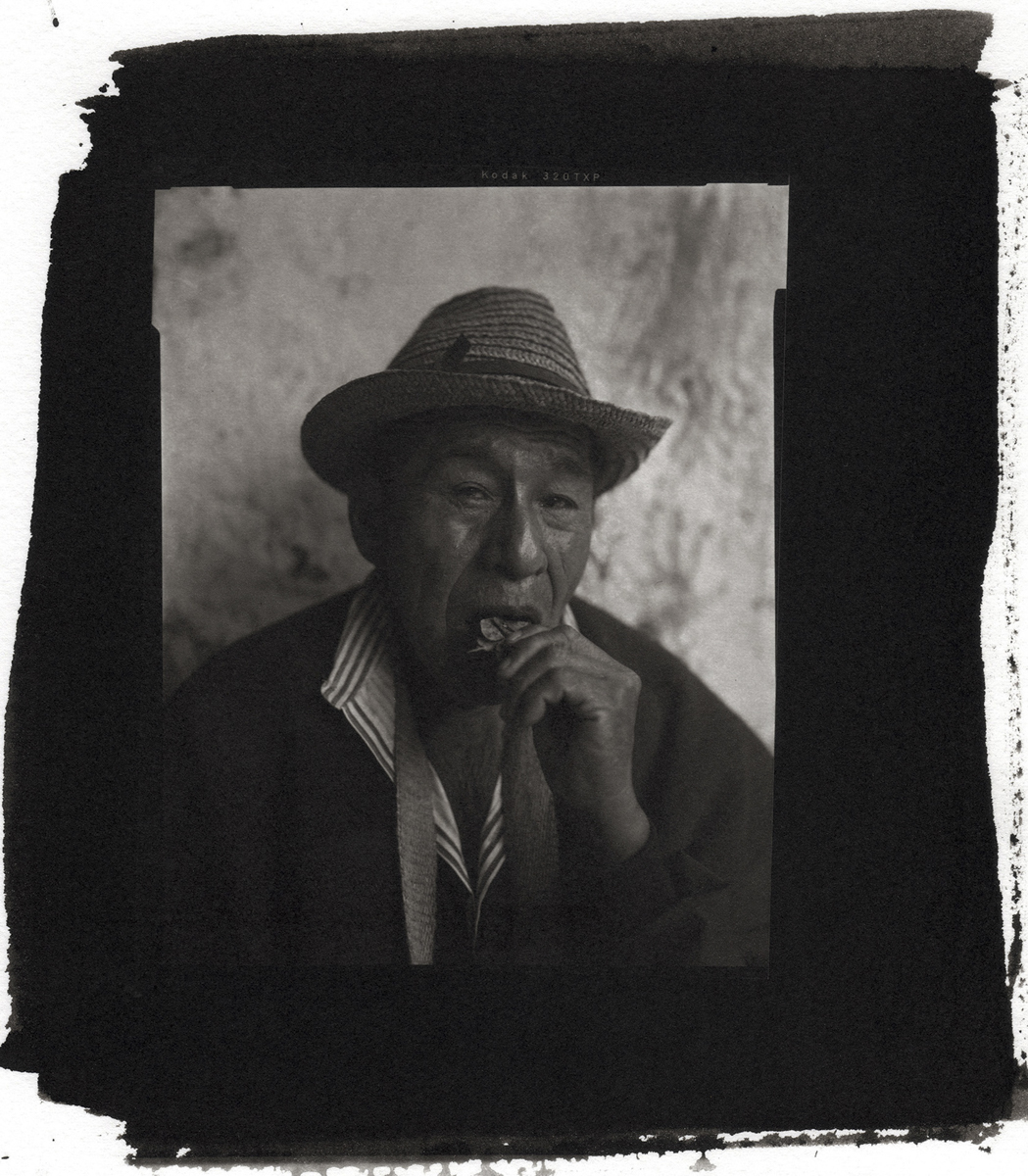

In 2017 I started traveling to Cauca with my 4×5 camera. I witnessed the Saakhelu ritual of the Nasas. Traditional doctors come, cut down a tree, open it inside and prepare water blessed with coca leaves. It is a very beautiful ritual because people dance and catch the water and bless everyone. I wanted to think about this problem from the point of view of the coca leaf, since in Colombia they don’t make that distinction: coca is cocaine.

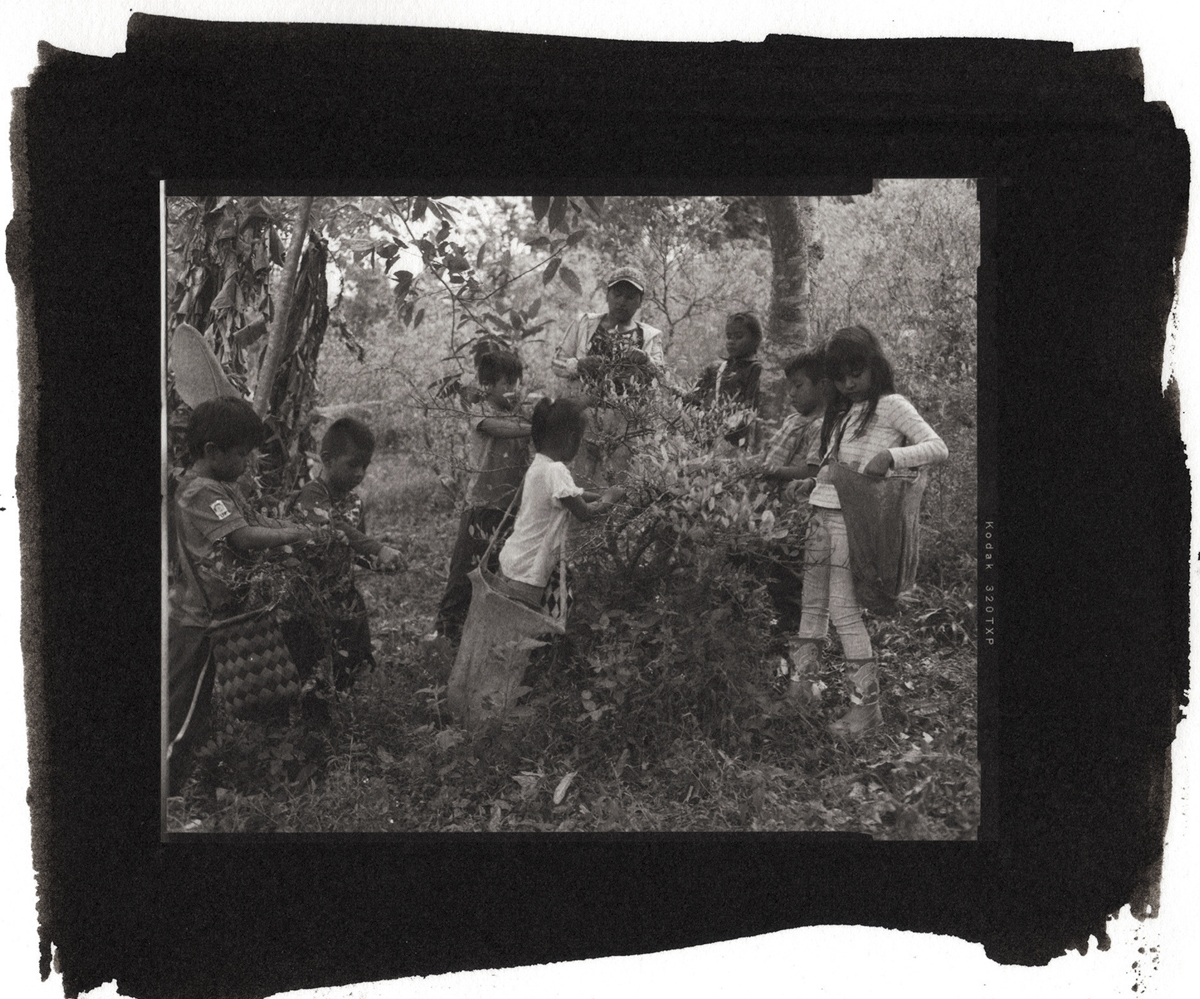

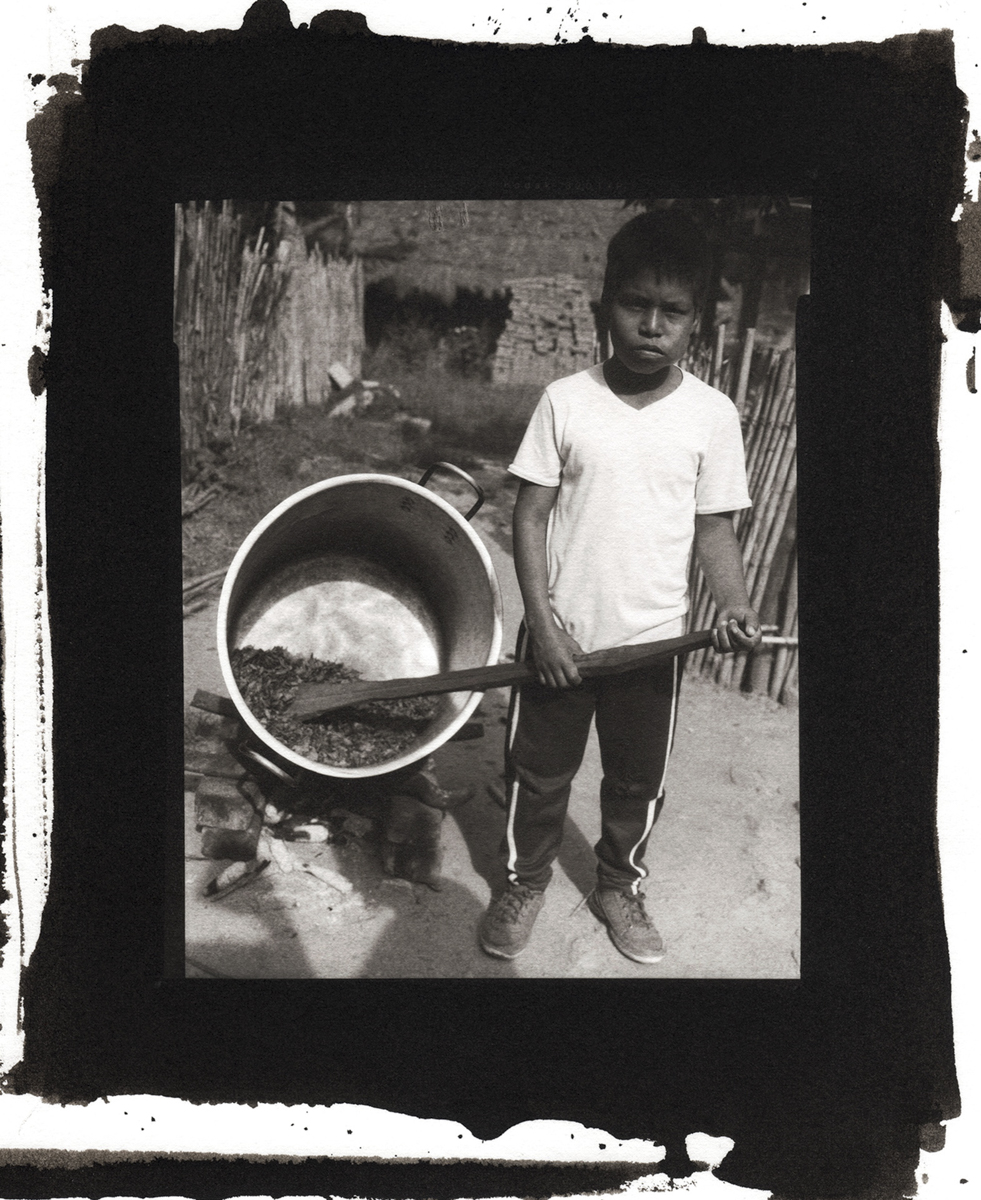

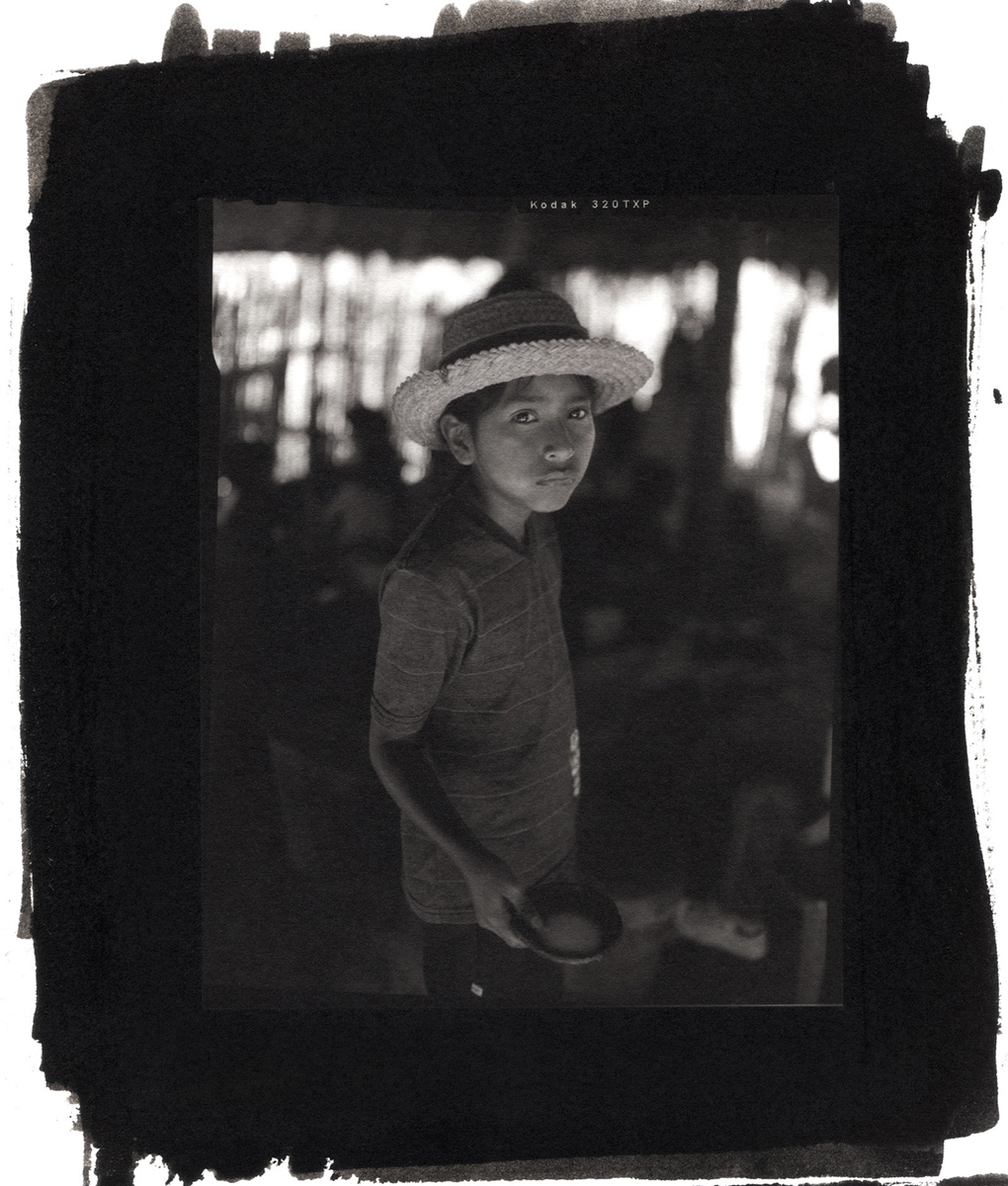

In one of those events I began to work the coca leaf. A doctor took me to a school and I found it incredible. That is the work I presented: a school called Wasak Kiwe. That’s when I found this traditional doctor who allowed me to go to classes. I asked for a permit to be able to enter with the 4×5 camera, to visit them, so that I could even enter the sacred house. I made many trips to be accepted and the result was these incredible images.

I also understood the importance of weaving. Weaving the bags that are hung to collect the coca leaf seemed incredible to me. Share with the children learning the ritual. There is also the photo in which the musicians appear, all students of the school where Nasa Yuwe is spoken, and where they always accompany the classes with their instruments.

The the’wala (traditional doctor) is the one who teaches the ritual of the leaf and ancestral herbs, but all based on the coca leaf. The teachers are the ones who work the weaving. It seemed incredible to me, it is very nice to have this little school in Colombia that returns and rescues the tradition of the coca leaf. That is why I titled these images Coca but in the Nasa Yuwe language because for me it is very important to work with the language of each indigenous community.

You also put a lot of emphasis on the violence behind drug policies.

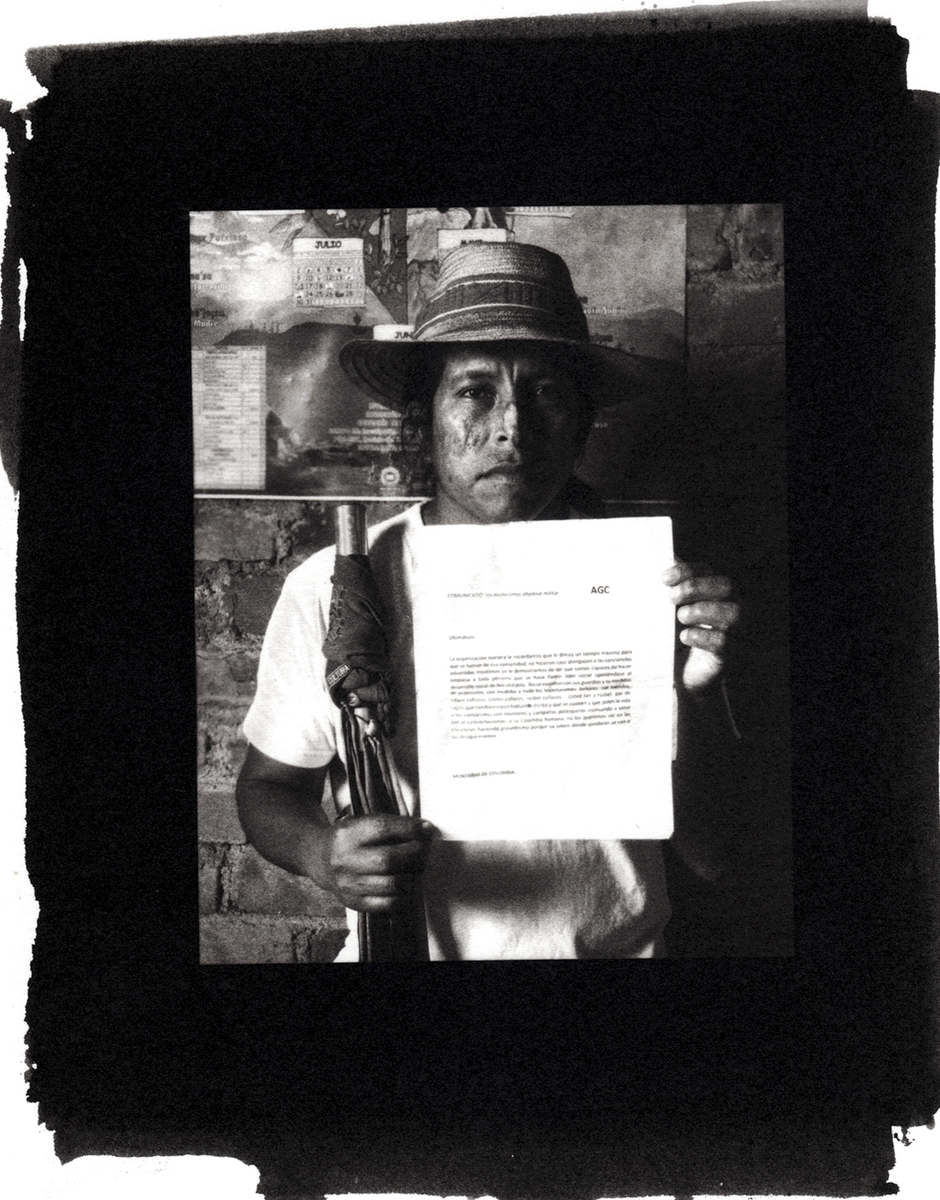

It was necessary to show the side of violence. The war on cocaine, which is not the coca leaf, is killing everyone, and it has taken over the entire country. In the Cauca region, leaders are murdered every day and there have been massacres during the pandemic. The work shows the beauty of the children in school but in the end the reality of the cocaine war has affected the Nasa.

So, the project that they will do with Estefanía García Pineda is a continuity of this work that you did at school in Cauca …

Yes. I have a nice relationship with Estefanía because in 2018 I won a grant from the Colombian Ministry of Culture to continue my work in Cauca that had started in 2017. I got to know a place called Popayork, the first indigenous cultural proposal in Colombia that It is directed by an indigenous Nasa named Edinson Quiñones and he is a great artist who works a lot on the subject of the coca leaf.

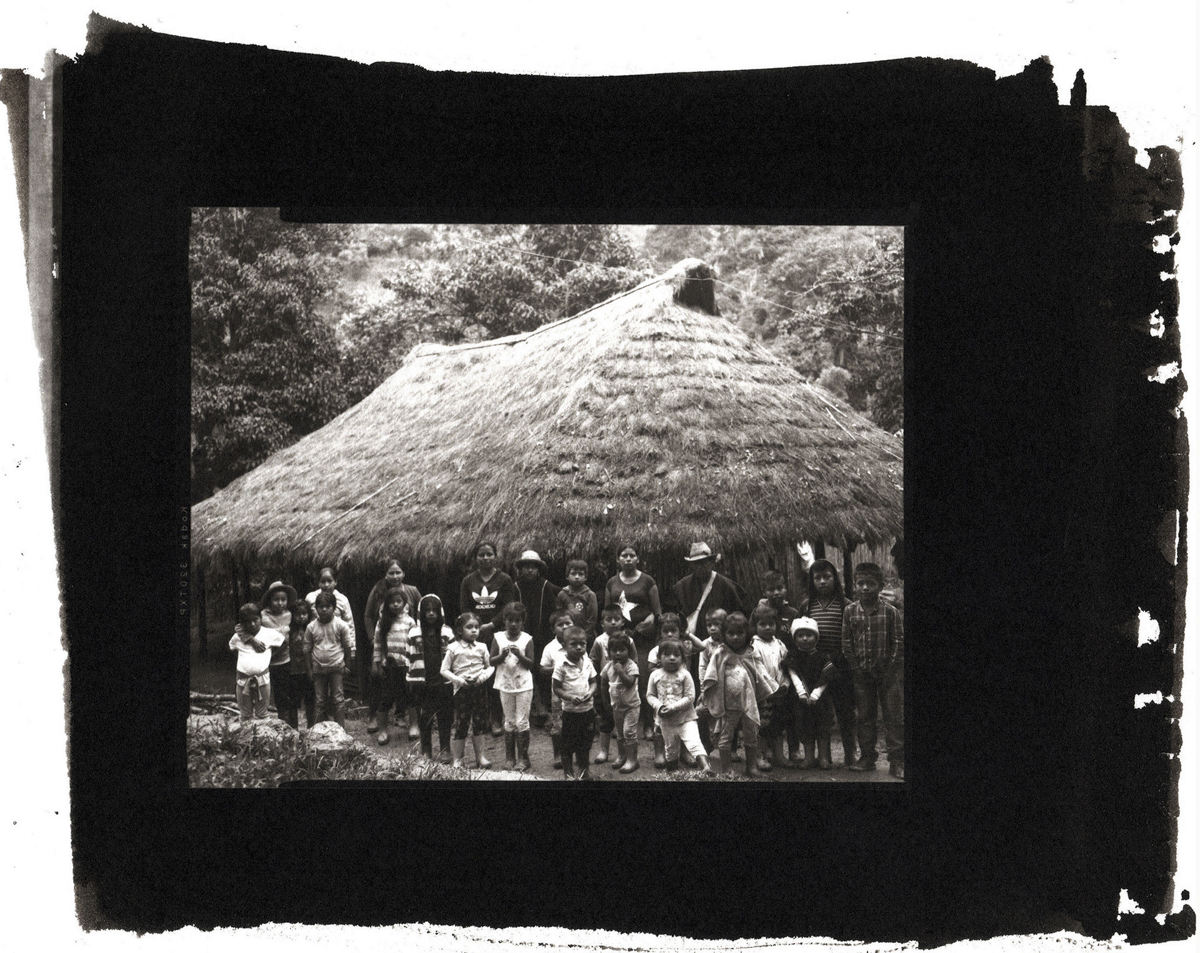

In 2018 I met Estefanía and Edinson and they took me to the shelter where I finished these photos. The Kitek Kiwe people are survivors of a 2001 massacre carried out by the paramilitaries to control the cocaine business in the region.

The first part of my work was the little school, everything ritual and photographing the children making the weavings. The second part involved looking for the effects of the cocaine war on the Nasa community. In that shelter they told me their story: they have been living a displacement since 2001 and they have finally been able to establish there, a space they called Tierra floreciente (blooming land). Last year I exhibited with Estefanía. I knew she was working on the coca leaf paper and it seemed incredible to me that we could take those photos and reprint them on paper made with coca leaf.

It’s wonderful for the school because everyone works hard on it and this project is going to make them produce. It is a symbolic act of recovering the coca leaf because they lost all tradition with the massacre. When I visited the reservation there was not a single plant. This is an act of appreciation to the community. It is an act of giving back to the community.

The participation of Vist Projects will allow the workshop to take place, they will support teaching about the coca leaf. I don’t have that knowledge but Estefanía does. I hope to meet virtually, I will be there with them and Estefanía will teach the workshop. We invited three teachers from the school to learn the knowledge, and we invited the governor who is going to pass this knowledge on to the The’wala and one of the family members of the leader who recently died, assassinated.

This is a co-creation because it is a symbolic act to give the workshop and, in the end, we will have the paper. And the most beautiful thing is that there will also be an exhibition where the video of the workshop will be shown and the people learning, taking this knowledge. We hope to have some photographs printed on the coca leaf paper that is part of that knowledge and process of giving back and working collectively with the community.