This week began, after many previous attempts, a trial against former President Alberto Fujimori for his “command” responsibility in the cases of men and women who were forcibly sterilized during his tenure in the 1990s. He together with three officials of his government are charged in the cases of 5 deaths and 1307 serious injuries to people resulting from these medical procedures.

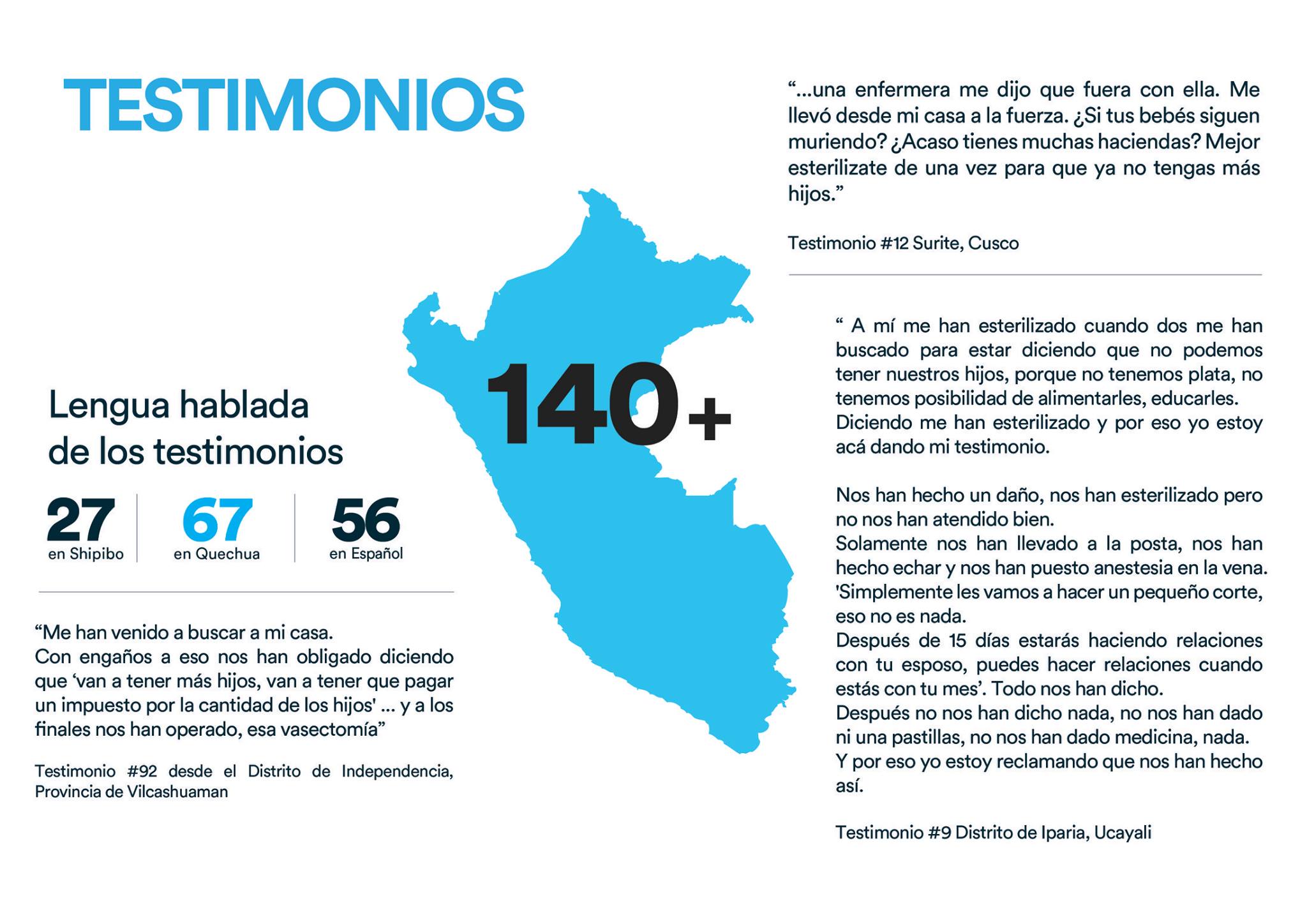

Although these numbers are impressive enough, it is estimated that during Fujimori’s government, approximately 290,000 people were sterilized against their will. The majority were women, and at least 22% were rural Andean indigenous people who could not read or write Spanish.

In 2012, the Peruvian documentary maker Rosemarie Lerner and her colleague Maria Court decided to make a documentary that would allow this story to be told in a different way. At that time there were already some records and documentaries, but in almost all of them the women were shown as victims or simply talked about statistics, Rosemarie and Maria realized that these women were activists and that they themselves had been telling their own history in search of justice for several years. So they designed, together with a production and research team, a platform to collect and amplify those voices: the Quipu Project. A week ago we presented the first part of the interview with one of the project directors. Here we publish the second part of the dialogue

Thinking about the multimedia and multiplatform nature, what role did radio play in Quipu?

Radio is the medium with the greatest reach in rural areas. You can get everywhere, but it is still a one-way medium. But the role of radio in these communities is incredible. It is a totally different relationship than the one we have. For example, we started in Huancabamba with Mrs. Esperanza Huayama, who is in fact the main character of the documentary and she is the main local producer of Quipu, she is incredible. And she was really the one who took on the project as something to take to the ladies. She said I arm myself with my phone and now I’m going. The first time we arrived in Huancabamba, she was president of the Women’s Association. She said, I’m going to convene this first workshop. The organization brings together ladies from the different villages, towns that are throughout the province, in some cases it takes eight or ten hours to get to the meeting place. And normally, when they have meetings of the organization, they notify by radio.

So it was like “I notice and they will come, the ladies will come.” “But how are you going to tell them? And will they arrive tomorrow? I mean, there is no way ”. I said well, if five ladies come, we do the workshop. And she would go on the radio and say “There is going to be this workshop. Come ladies friends, I don’t know what, in the woman’s house ”. I said heck, no one is going to arrive. And suddenly, the next day there were five women. A couple arrived the night before, and I said oh that’s great, with them we do the workshop. There were five of them when I started and suddenly they kept coming, more than thirty ladies kept coming. Just because of having called on the radio from the day before or two days before. Later, on the second trip, I remember that we were also at the little hotel and our bus would leave, for example, at one o’clock and the ladies arrive and knock on the door: “Your bus! Your bus will leave at twelve an hour early”. And I, but “how does she know?” And they: they have warned on the radio and I was like, how is it going to be that they warn you on the radio.

Communication on the radio is so common that even the bus if it goes ahead they tell you by radio, because everyone in the morning goes to work in the fields and they go out with the little radio and they are listening all the time. The radio is super powerful there. Besides, there are many local radio stations and their role in the community is very important. Our allies were the radio stations, little stations of a man in a house. Those were our main allies to reach different parts of each province.

And the phones?

There were ladies who didn’t have a phone, but there was always at least one neighbor or someone. In many cases the ladies did not know how to operate the telephones, but their sons or daughters always know. Sometimes we made the call and they came with their daughters to the workshops, so we trained the daughters to help them.

We also did something more symbolic. For example, we went to Huancabamba or Cusco and in that first meeting we met different women who came from another region and represented another group. Then we would meet them, to go visit them and they would gather the ladies. There we did the workshop and we left for a woman per place, mobile phone for the Quipu project. That lady was the ambassador of the project in her community. So, if a lady wanted, she knew how to use the mobile and if someone wanted to call she could go find her. Esperanza, in many cases, went with her phone to collect testimonies, but she was the only one who did that.

As for the digital divide, do you really think that it was possible to overcome a little bit in this case?

Yes. For them it was very clear: “now our voices are heard in other countries. People know what happened”. There has been a claim, even though it is not a dialogue, if you want, so fluid. But there is a connection that there was not before, because before they could not, not even in Peru, be heard on a television program. Suddenly, now, having this certainty that they have been heard, they feel that there has been an impact and they feel recognition.

And Esperanza, well, she herself is particular, because Esperanza has had personal growth. She welcomed the project and it has been like an excuse, for a personal growth that she had already started. She, from being an illiterate woman, peon of a farm, ended up being the president of her organization and the vice president of the National Organization. During the production of the Quipu Project, the first National Association of Sterilized Women is formed, and that is when the groups we are working with come together. I must say that Quipu helped in the sense that we created spaces for them to be together and this is how this network was strengthened

In the short film I was struck by the fact that she says that before they did not know what communication was. What did she learn from communication, what does she mean?

In the first workshop, I remember that I told the ladies “this is about telling stories, we all know how to tell stories.” And all the ladies: “No, no. We don’t know how to tell stories”. In the workshops we did exercises where there were some ladies who spent half an hour and they continued to tell and on. There I said: “t that is communication, it is what you are telling, you are telling your stories.”

I think that what Esperanza was referring to is that she did not feel comfortable, they did not feel comfortable telling their story, they felt that they were doing it wrong, that they were clumsy. And this was due, in the Huancabamba case particularly, to the fact that shortly before our first visit they had received a visit from a prosecutor who had treated them horribly. She had asked them questions like what date did you get sterilized? What time? What doctor?

The general feeling these ladies had was that they had failed in this interview with the prosecutor and they said “it’s because we don’t know how to speak, we did it wrong, they won’t listen to us”. I think we vindicate them by telling them you know how to tell stories, letting them freely tell them and also going back and making them listen to the stories of others. They viewed the phone line as an opportunity to rehearse or practice before their new statement in front of the prosecutor. They said now we feel more secure, now we know how to tell the story. That was super nice because it was a particular use that they found themselves.

And Esperanza was already in this process prior to the Quipu project, but what the project did was give her more opportunities to practice and prepare. When we traveled, she was our representative, and when they went to interview her she always wanted to practice and rehearse how she was going to say things before. I think the project gave her that validation, but also the opportunities for her to prepare herself more and more, improving her speech, the way she speaks. I think she was referring to that too.

There is something very beautiful about the voice, because it is their voices, not only their stories, their ways of telling, but their voices, literally, that one can hear.

Yes. While we were doing development in England they told us that it was necessary to do dubbing. I said: “No way, this voice that has traveled 10,000 kilometers we are not going to do dubbing. There is no way”. For us it was a basic question, because our call to action was always listen, listen. They told us it is a reading experience too. And I don’t care if they read, because the important thing is to listen to the voice.

At the beginning we didn’t know how we were going to present the stories either. We thought maybe we were going to have to edit or cut. But with the first testimonials I started doing tests and I realized that when I tried to edit I couldn’t cut them. It was wrong to do that. And those things were the ones that in the end were defining how the project was carried out.

From the beginning you thought of three audiences for the documentary. Sometimes people do things without thinking about who is going to receive the projects.

When you are a documentary maker and you come from documentary or traditional cinema, usually you don’t think about that either. But we decided to do a transmedia project and we were also learning, we had a lot of people who advised us and we got into workshops. And that helped us to think about design thinking.

When you want to tell something, especially when it is something online or something interactive, you have to think of the user first. In other words, you can’t just hit it, you have to do short iterations and testing all the time.

There we began to identify the user groups with whom we were going to work and for us the main thing was to build a community with the affected people and their communities. In other words, this offline audience was easier for us to identify. It was different from how we were going to reach the international audience, for example, through the web. The last audience were the most dominant or political classes in Peru, in Lima. That was also clear to us because we knew that Peru is one audience and the international audience is another. That audience we knew was the most difficult and probably the one we least reached. I would say that we knew that because it was the most difficult it had to be last, because that audience is not interested in what the first says, but they are very interested in international opinion. So our tactic was to create international awareness on the issue, to talk about the issue and only then would these people in Lima become aware.

That came from changing our way of thinking about methodology and thinking a bit about UX Design, Design Thinking, thanks to people who came to help us change that chip that we have as authors, where I tell my story and you see how you consume. In this case it doesn’t work because you require an interaction, a click. So you have to be thinking all the time about the user: how do we make the lady really do the call and want to tell her testimony. It is a collaborative co-creation process, it does not depend only on us.

It was super long because the first year we brainstormed how we were going to do it and we had a thousand ideas. A tool that helped us a lot was The Impact Film Guide by Doc Society (ex BritDoc) and it is to think about impact campaigns for documentaries. This is because I do see the documentary as a tool for political transformation. And this guide also helped us a lot to map and see how we are going to do the project and what are the impact dynamics that we want to follow and therefore also think about the audiences. Also because we had to think about distribution from the beginning of production. The process is different if I make a linear film, here from the beginning because of the platforms it was going to be on, we had to think about distribution.

Sure, because this documentary was more than a political tool. It is political in his conception, with a very clear political stance and with a political intention.

Yes, I see the documentary in general as a tool. It doesn’t always have to be this way, there are other types of documentaries; but it has the potential to achieve impact and social change. What catches my attention and I like is being able to reflect and draw attention to certain topics, but generate an action from someone. The transmedia or interactive documentary allows us to see that in a much clearer way because it is immediate. You see if someone clicks or if someone responds, the effect is different. I believe that digital media greatly enhance this possibility of the documentary, of generating impact, of measuring it and being able to know how to do it.

And also for the participatory and collaborative characteristic. There it changes in the sense of saying I am the one who goes and tells a story that I am seeing, we are going to build the story together.

Yes, that was difficult for us. I’m not going to say no. María also came from the same, she had a journalist’s past where you tell your version. Opening the process suddenly, when one is an author is difficult, besides, you don’t know what will happen. We decided to make the framework, the platform and curate this to find a way that, using our experience as communicators, the stories are accessible to more people. But the content of the story is variable, that is, new testimonies are arriving. And there is a question of letting go, because sometimes when you are an author you want the minimum control.

Actually, when we create the platform and the first testimonials began to arrive, it was an incredible feeling to say this is working, we are participating and it really is a collaboration. It does take a chip change, but it’s so much more rewarding when you really collaborate and do something together.

It was a beautiful experience and, in general, co-creation, participation, is something that interests me. Probably what interests me most about new media are these possibilities of co-creating. I’m not saying that I’m not going to make a documentary by my own, mine and closed. That, I’m going to do that too. But I am very excited about this possibility of co-creation and of focusing not so much on the final product, but on the process, on what is gained in the process and on how to really democratize all the stories and how they are told. That people have agency in how they are represented.

We have been very used to always seeing the vision of the filmmaker, the European who comes and makes the documentary of the poor person from the Andes and leaves, or the person from Lima, or from the capital, from Bogotá who goes and does this. But we lack precisely that congregation and that variety of views that focus not on the final product, but precisely on all these new things that come out in the middle.

Many interactive documentaries are hosted on web pages. With Quipu it happened that at one point it stopped working because of technological changes. How do you think that or accept that they will have a short life?

I think that is something you have to think about from the beginning. I remember that I said to myself, if it is going to be on the web, let it be there forever. We had an advisor who said if this is a living documentary, because we said Quipu a living documentary, at some point it has to die, right? And she was right, technology also changes. On December 31st, technology was gone and many interactive projects stopped working, due to an update. One always has to think that not because it is online it will be eternal. In our case, we were not prepared for it to stop working, but we were clear from before what we wanted to do with the project’s legacy. We made sure, in the case of testimonials, that they were protected. That is why we did this with the University of Bristol and the British Library. And we made an official delivery to the LUM, something that for us is super important and symbolic.

Now we are making a mini web where we are going to put, let’s say, the whole summary, everything what the project was, because also the case continues. We continue to share things on Facebook, we remain vigilant and we do not want the project to disappear, especially if justice has not yet been achieved.