The 2011 presidential elections in Peru were led by Keiko Fujimori and Ollanta Humala. Throughout the campaign, Humala used as one of his workhorses against Keiko the issue of forced sterilizations that had occurred during the presidency of his father, Alberto Fujimori. Although people like the documentary filmmaker Rosemarie Lerner had heard something about the subject, she had never understood the scale of the event before.

An estimated 272,000 women and 21,000 men were sterilized in the 1990s. Most were indigenous Andean women. Despite the fact that there are other cases of forced sterilizations in the world, none have had a similar magnitude. Rosemarie was scandalized. At that time she was pursuing her master’s degree in documentary film in England and she became interested in the subject.

It was thanks to Giulia Tamayo, the lawyer who uncovered the scandal in 1999 when Fujimori had not yet been dismissed, that she decided to make a documentary. “The more I knew about the subject and the more I understood the magnitude, I realized that this was not simply a story of the past, of what had happened in the 90s, but that there was a present story of the current struggle for justice from the ladies who weren’t being heard. ”

Just at that moment Rosemarie began to hear about the transmedia documentary and, understanding its possibilities, she got excited and decided to speak with Maria Court, a Chilean colleague with whom she had studied her master’s degree and who was doing another master’s degree in Screen Documentary. She told her the idea and they began to design tools, not to tell a story in the traditional way of an author and a story, but to amplify the voices of the ladies who were already telling her own story. Thus was born the Quipu Project, a live, interactive and participatory documentary.

In Rosemarie’s words: “The quipus were knotted ropes used since ancient pre-Inca civilizations to store information and pass it on between generations. The name of the Quipu Project is inspired by the participatory work with the communities in the intention of weaving together these individual experiences in order to tell together a collective story from the point of view of those affected”.

Between 2012 and 2017 Rosemarie, María and a research and production team designed a whole platform that allowed: collect the testimonies of the ladies through a free telephone line; moderate and curate the audios received in Quechua and Spanish, transcribe them and translate them into Spanish and English; host and disseminate testimonials through a web platform; collect testimonials from users of the website who heard the stories of Peruvian ladies and disseminate them.

All this thought for three audiences who they wanted to impact in different ways. In the first place, the victims of forced sterilizations, whom they identified from the beginning and with whom they proposed to build networks of support and solidarity, inside and outside Peru. The second audience was the international public, as they were sure that by reporting this situation outside the country they would be able to generate pressure within. The third audience was the Peruvian ruling classes and the political elites. With the three audiences and having begun the construction of support networks, they began the second phase of impact: changing mentalities. They knew that if a Peruvian listened to the testimony of the voice of one of the affected people, they would very surely change the position of others in this regard. For this they also produced a short documentary with the support of The Guardian.

A total of 174 testimonies and 132 responses were collected in 127 different countries. Clarity regarding the chosen audiences and how to impact them has to do with the political nature of the documentary and its interactive format. To effectively build a community, they needed audiences to be protagonists.

That also implied understanding something that was difficult to assume, if Quipu was a living documentary, at some point it would have to cease to exist. And to some extent that happened last year, when the platform stopped working due to a technological change. However, Rosemarie, María and their team made sure that the testimonies were protected: they are currently housed in the British Library, where they will rest for at least 30 years. And last year they officially delivered the file to the Lugar de la Memoria, la Tolerancia y la Inclusión social del Perú (LUM). A few days ago, the affected women were included in the Comprehensive Reparations Plan and will be compensated.

Where did the Quipu Project come from?

I studied audiovisual communication and in my undergraduate degree here in Peru I did the only course documentary that was in that career, which was an elective course. Here in Peru, at that time, very little author’s documentary was known. Documentary was National Geographic, Discovery Channel stuff. I was immediately interested and started working with Docu Peru and decided that I wanted to study documentary film.

In 2010 I went to London and did a master’s degree in documentary film. Right at the beginning of 2011 in Peru there were presidential elections, Keiko Fujimori, the daughter of Fujimori, the dictator, and Ollanta Humala, who was the opponent, was running. He began to use in his campaign to attack Keiko, who sold herself as the first woman president of Peru, the issue of forced sterilizations. The case of this massive violation of human rights that had occurred during the government of her father. And the truth is that just at that time I had heard something about forced sterilizations, but I had never really heard what the magnitude of the case had been, nor did I know many details, it was just one more line to the tiger, let’s say, of all the acts of corruption and crimes of Fujimori. Furthermore, the Comisión de la Verdad y Reconciliación did not review the issue when they did their research on the years of political violence.

I could not believe that this had happened to so many people, especially so many women in Peru and even more, I could not believe that I didn’t know and that most people didn’t know the magnitude. It was there that I became interested in the subject. At the beginning my idea was to make a traditional documentary, because that’s where I came from, right? I wanted to investigate and tell a linear story.

What prompted me and made me do it is that the mother of my best friend from school was Giulia Tamayo, the lawyer who uncovered the issue of forced sterilizations while they were still happening in the Fujimori government in 99. She was threatened and had to leave the country. Being in England I decided to get in touch with her and talk to her. Giulia was my main source of information. What she told me every time left me more shocked and I understood the need to tell a story not only of what had happened, but that there were still many groups of women who in some cases had been fighting for justice for 10, 15 years and they weren’t listening to them. There were grassroots organizations in Peru, with women leaders in Cuzco, in Piura, in the north, in Huancabamba, and she introduced me to these people in order to learn more about the subject.

Another thing that happened is that while I was in England I discovered this world of interactive documentary, of transmedia that was just beginning, it was incipient, even in England. I was lucky enough to go to the Amsterdam Documentary Festival, the IDFA Academy, which was a school, and there they began to talk about interactive documentary at DocLab. There I decided to approach María Court, who is the co-director of Quipu and was my partner in school. Also, after that, she was studying a course called Creating Social Media, precisely to see how to tell transmedia stories.

With María we decided to look at the tools and see how we designed something, not for us to tell the story, but for us to realize that they were already telling it. There was no need for us to count it for them, but what they needed was a platform for her voices to be heard. That’s where the idea of Quipu was born. How we can be communicators and through new media, give people who were on the other side of the digital divide the same opportunities that many of us now have with the Internet. And particularly, because what we saw the most was that in this whole campaign issue, suddenly, forced sterilizations became a crucial issue and everyone had an opinion, “everyone” was talking about it, except the affected people. They never had a space to participate in this dialogue that was already taking place. In addition, we saw that, in the journalistic programs, in the documentaries that already existed, they were treated as victims, they were treated as numbers, statistics and it was always this image of the Andean lady crying. They were images of any Andean lady and we thought that was wrong. First, because knowing the ladies, we realized that they are not victims, they are activists. We did not want to represent them as victims, because they are female fighters, who do not stop, who are actively trying to move their companions, because they are very clear that they do not want this to happen again and they do not want it to happen to their daughters. So we decided to do something with a totally different look, where they are responsible for telling their own stories.

There we began to experiment with new media. The first challenge we had was how to create a co-creation platform with people who are on the other side of the digital divide, with people who live in isolated, rural communities, and who in many cases do not have contact with each other either. Because the sterilization thing happened throughout Peru at national level, but many of these groups that were organized were many miles away. We met people from small towns who until the moment we spoke with them, thought that the sterilization campaign had only happened in their community. In other words, they did not know that there were hundreds of thousands of women who had the same history as them in the jungle, on the coast.

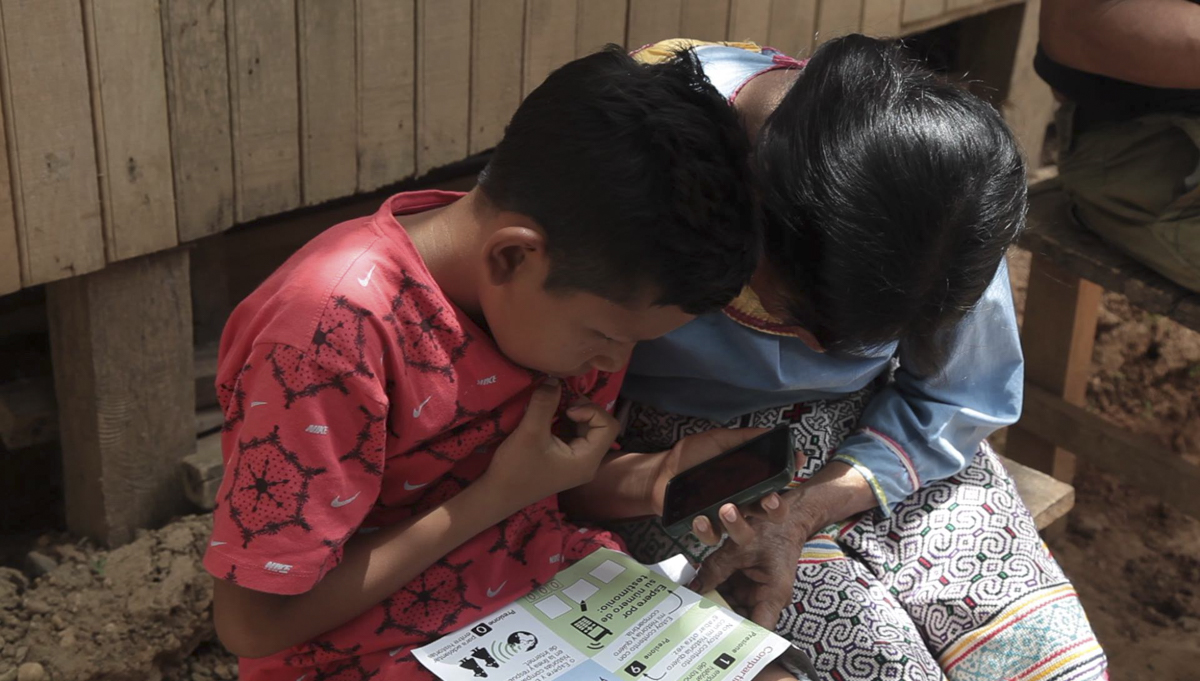

We wanted to make, first of all, a platform that can also help them build community and connect with each other and at the same time that they can be online and can connect with the rest of the world. With a group of people, including Ewan Cass-Kavanagh, the programmer, we discovered that regular phones could be connected to the web. We started doing experiments, we went and did tests with the ladies to share the testimonies in different ways and then we went back to see which ones they felt most comfortable with. From the beginning, everything we did was based on workshops, with women’s groups and we co-designed with them what the final form of the project would be like, so that at the end this interaction could be seen on the website.

The ladies could call a toll-free number that was available in Spanish or Quechua. We could not do it in more languages, due to accessibility issues, but in Quechua it was very important due to the number of Quechua women who were affected. Women could call the line and either press one to tell their story or press two and hear the stories of other women.

We got to know the different groups, traveling with them and did workshops to teach them how to use the line, but also for them to listen and connect the stories of women in other parts of Peru. The development of the project went like this: in 2011, the idea occurred to me; In 2012, I started working with María, and the development was until 2015 when we launched it and the project was, let’s say, alive until 2017. In other words, I could still receive, because on the website there was also the option for any user anywhere in the world to leave messages of support that were posted on the web and sent back to the phone line so that women could also hear messages from different parts of the world. The platform was running from 2015 to December 2017.

At that point we had to close because it was not automatic, there was a whole moderation system. Something we had very clear from the beginning working with academics from the University of Bristol was the ethical part. We didn’t want to make the same mistakes that had been made during the sterilization campaign, that is: not considering the language, not considering certain conditions of the affected people. We did not want to impose anything on them, informed consent was essential.

That is why we held an ethical meeting in which it was decided that we should moderate all the testimonies, there had to be some kind of control. It couldn’t be a free page, where any hater could come and tell any lie. So there was a moderation process where we checked that the testimony was well recorded, the audio quality, etc., but also that it did not break any of these criteria.

At the beginning we had not asked on the telephone line that the testimonies be anonymous. And it was striking that almost all the ladies when they started their call said: Hello, my name is such, in some cases they said my identity document is such and this is my story. I think there was a need to vindicate them and to identify themselves. Saying this is my case, they haven’t heard me before, this is me and this is what happened to me.

However, as we were getting closer to the launch of the project, the 2016 presidential elections were approaching again and many women in various places began to receive threats or in some cases they were afraid, because in many cases the people who serve in the health centers are the same people who operated on them in the 90s, so they were afraid of reprisals. There we made the decision together with them that the testimony file would be an anonymous. We reviewed all the testimonies, took out the names and changed the telephone line to ask people to please not give their name due to a protection issue and also because we knew that this type of testimony was not going to have legal weight in courts for how it was collected.

It was a lot of work and it had to be cut at some point, so in 2017 it closed. We did a closing workshop with the main representatives of the communities with which we had been worked and with academics from the University of Bristol who came and we all went north to Huancabamba, and we had a joint closure of the project with the ladies.

The size of the sterilization campaign is impressive. But also everything that was needed to make the documentary.

Yes, our team has varied and has been multidisciplinary, which is what is needed in this type of projects. Multimodal, if you want. In other words, at different stages we have done different things. And the work with the ladies and also with women’s organizations here in Peru that were already helping, because it is not true that Quipu suddenly created this fight for justice, there already existed and there were several organizations in Lima that were also helping some of these groups. And we have just coincided with a movement of young Lima artists and intellectuals and people who have begun to carry out other types of initiatives to generate attention on the subject. Quipu arrived at this precise moment, and what it helped was to give it international knowledge or relevance. Because in Peru many people did not know about the subject, internationally nothing was known. When I was in England and I was commenting on what had happened, people didn’t believe me.

In the United States, for example, in North Carolina, in Virginia, women who were sterilized without their consent in the 70’s have already won lawsuits. Obviously the numbers were much lower, but it has happened in Sweden, it has happened in Israel, has happened with Roma populations in Europe. It has continued to happen in prisons in the United States.

Obviously, the numbers in those cases are never as scandalous as those in Peru. What happened in Peru was a subtle genocide attempt. But it is not Fujimori who has this idea out of nowhere, this comes from before, in the Kissinger Report it seems that there is talk of these eugenic practices, for example.

It is a clearly eugenic practice.

Exactly. In the investigations we find that there has been a military plan of the government of Alan García of the eighties prior to Fujimori, the ‘Green Plan’ that mentions the use of sterilizations to control the surplus population and reduce population growth. It’s just that Fujimori reaches a point of such pride. He believes that he can do something of this magnitude and get by and so far he has. I think the trial was shelved like six or seven times. Just now, again, the last hearing had to be canceled because there was no Quechua translator and now they have moved it to March.

Progress has been made, but there are still many women who have died waiting for justice. That’s the truth. And that they still live in desperation because they were not recognized either in the Registro Nacional de Víctimas that was made after the Comisión de la Verdad. And, as I told you, in many cases they still have to face the people who did this to them in their own health centers. It is quite a complex situation.

There were many more women affected. Why do you think that happened?

Well, I think that is something that happens worldwide. Peru is a particularly macho country, and especially in rural areas. I think it is a tendency to blame the bellies of women for the problems of the world, for poverty. And here, in such a macho country, convincing men to have vasectomies is much more difficult.

In many cases the women were operated only with the authorization of the husband. For them, if the husband signed the authorization, that was valid. In many cases, either he or she had to be chosen, and it was obviously going to be her. And in many, many cases it was literally forced, or they were tricked or sterilized after a cesarean section or when they were undergoing another procedure. There are also cases where they wanted, for example, to operate on her wife and the husbands said no, not her, you do it to me. I do know cases like this, but they are a minority.

The health personnel had to sterilize, for them it was much easier to go to the women at their homes, chase them, torment them than to convince the men. And there is an issue of masculinity, virility, a sterilized man is branded as homosexual. Many women are also told that they are lesbians or that they have had surgery to be able to be with many men. In addition, there is this whole question of the Andean worldview, where a woman who cannot reproduce loses value and is stigmatized by her communities, even worse when she has been left with physical consequences and can no longer work the land, then she becomes useless and a burden. for local communities. Which is terrible.

This also suggests the limits between promoting the freedom to decide about the body and a eugenic practice.

Yes, it is that he disguised it that way, he became the I am the feminist and now Peruvian women will be the masters of their destinies. That’s what he said. But in reality, instead of offering a wide range of contraceptive methods, what he did was take away their usual methods from women and promote this one method in a very aggressive way. And what was done was to establish sterilization quotas for a procedure that was even illegal before.

The calculation has never really been clear to me how it was done, but each region had quotas and health personnel had to comply. Kind of, in the Piura hospital they have to do 62 sterilizations a day and certain doctors got out of the blue and said “How is it possible? We don’t even have the infrastructure to do that.” And they refused and the same day they had visits from ministry officials who were going to intimidate them. The reports were made directly to Fujimori. The worst thing is that each place saw how it met those quotas. In some cases there were incentives, they gave prizes to the health personnel who did the most sterilizations. In other cases they were forced, threatened with dismissal.

There are cases of health promoters or nurses who, in order to reach their quota and not lose their jobs, underwent the procedure themselves. There are stories so, so varied. But in general what you notice is that everything was very bad and it is difficult in trials to prove everything. The problem was therefore at a macro level and at the central government, which was demanded. Health ministers who demanded fees. And obviously, there are individual responsibilities of doctors, of health promoters, but it is not a case that can be treated like this because it was systematic, it was massive and it came from above.

Precisely, in one of the videos, Keiko Fujimori says that responsibilities are personal. Did you talk to any of these doctors or promoters?

No. We did have some testimony out there, there was one from a promoter, but she asked that we not publish it. She told of the atrocities she had seen. We have spoken with some doctors, but in general they did not want to participate in the project. We speak with doctors who have written on the subject, academics like Dr. Gonzalo Gianella and he condemns doctors. He says that each doctor who did this has an individual responsibility. But it is very complex. Health promoters are also people who in many places live in precarious situations.