“My name is Ana and I’m a love addict”. This is the first statement of Neuromantic the work of the colombian photographer Ana Cristina Vallejo. Having recognized it and wanting to understand it lead her to start the project published this year in the talent edition of FOAM magazine.

Ana is a biologist and, even though she always took photos to remember and to capture some moments in her life, she came across photography walking through the streets of Cali in 2012. Neuromantic is the project she is currently working on. It was born from Ana’s interest in understanding her own ways of establishing relationships, but she wants to expand it and seeks to know the experience of others to “find patterns and connections between trauma, emotion regulation and addictions and how those factors feed intimacy”. To achieve this she is working with a data scientist with whom she created a survey they want to apply to a lot of people. The results, she hopes, will be part of the way she will present the project.

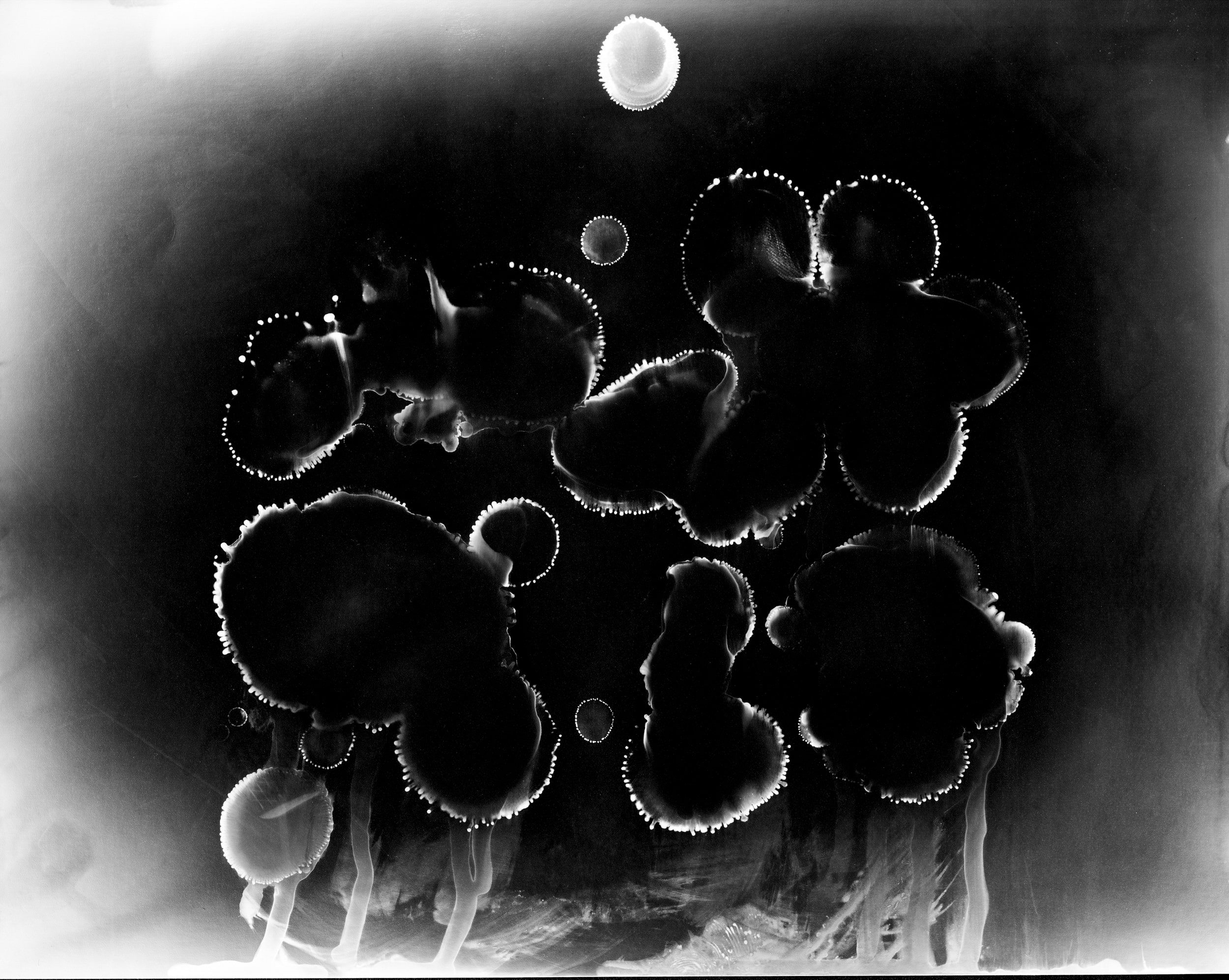

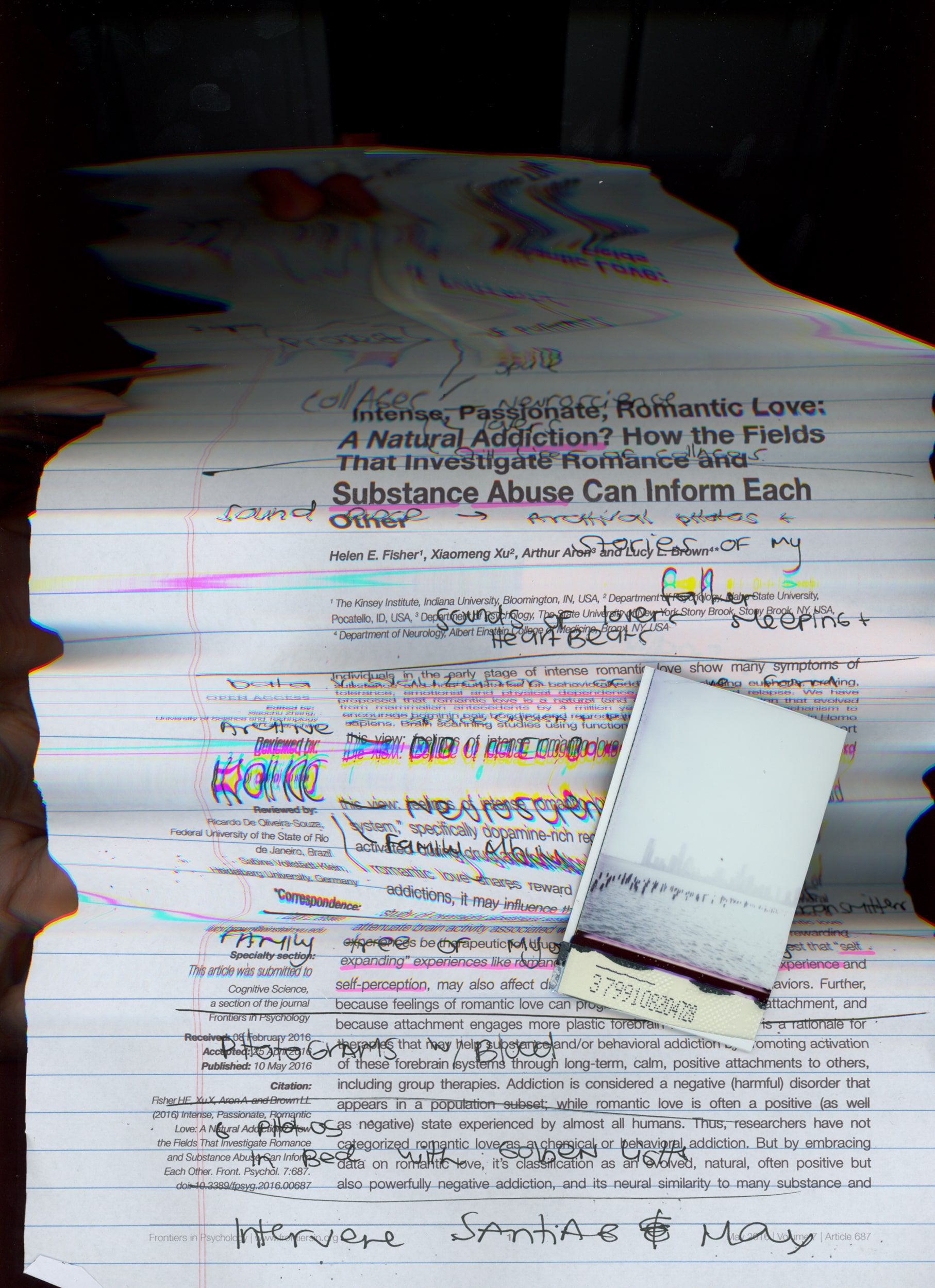

The title of her project is reminiscent of an album that she likes and in the combination of the words “neurosis” and “romance”. Interestingly, that is also the name of softwares that process electrophysiological data. Even if this looks like an isolated data, it is not: Ana wants to propose a relationship between art and science. For her, assuming that a person can be addicted to love implies that love generates a series of physiological reactions. Her research has lead her to observe how the brain reacts to stimuli produced by love. The hypothesis is that romantic love can act in the brain like a drug.

How did you start to take photographs, where did the interest come from?

I studied biology here in the United States until 2010 and then I came back to Colombia, kind of lost. I got a job as an assistant and went in the afternoons to the genetics and neuroscience laboratories (at the Universidad del Valle and the Universidad Icesi) and also on Wednesday mornings to the psychiatric hospital in Cali, to see the cases of patients who had there. At that time I was looking for me but I was not quite in science, and I had an obsession with human consciousness and understanding the psyche.

I know that big part of that motivation was because my father is schizophrenic. For a lot of time that was very difficult for me to understand and to know how to cope with it. And maybe there was also a fear of falling into that state myself, in that liminal space of not knowing if I am normal, or if I can lose my mind. I also thought about it from empathy when I felt that many people do not understand people who are different.

In Cali I found a photography school. I had always taken photos compulsively, but it was to remember things.I walked in by chance and loved it. So I say: this can be a career. It seemed more viable than biology and I told my parents that I wanted to change course. Then I went to study at Lasalle College in Bogotá. I remember that at first conceptualizing art cost me a lot, I came from science. I started doing documentary. Understanding light and composition took time, but I always felt a strong attraction to color.

How did you manage to understand all that can be very abstract and complex?

Little by little I started the first project which was Entre Nubes. With that project I learned a lot. The Croma Taller Visual workshops helped me a thousand times more than the school itself. I asked for reviews all the time. At first I went for the more classic side of the documentary. I arrived in San German, an informal neighborhood in the Entre Nubes nature reservation on the southern outskirts of Bogotá, and began trying to tell a story with pictures. I was wondering how to make it interesting? How to make colorful and strange photos that I don’t understand but that appeal to me? But over time I began to have a question: who am I, a person of privilege coming to this territory to extract a truth? I decided that this was not enough and I started collective initiatives for urban artists to go to paint houses there. Although I am a person who tends to feel anxious in large groups, there is something about collaborating that fascinates me and I think it has to do with my personality, that feels a need to connect and form synergies. My projects, being experimental and collaborative, take on a life of their own and are amplified and this fills me with life and motivation.

The idea was to see what can happen in an artistic exchange: small things like a neighbor meeting another inhabitant of the neighborhood. For example, the neighborhood was divided by race, blacks in the southern part and whites in the north, and they did not speak to each other. During the activities, the children below began to talk with those above, or one time a mural was painted on the side of a house and the next time the front of the house was painted in the same shade of pink that was used in the mural. For me those little details gave meaning to the project.

I had this question as to why the work you see from Latin America is always about social problems. Somehow I understand it, because it is impossible to escape from that common context with so many injustices: no matter how personal a project is, it somehow touches the political and social environment. But I wanted to feel more autonomy and the right to tell and I realized that I had to start from my experience. This has generated fewer contradictions for me than extracting a story.

You mean, speak in the first person?

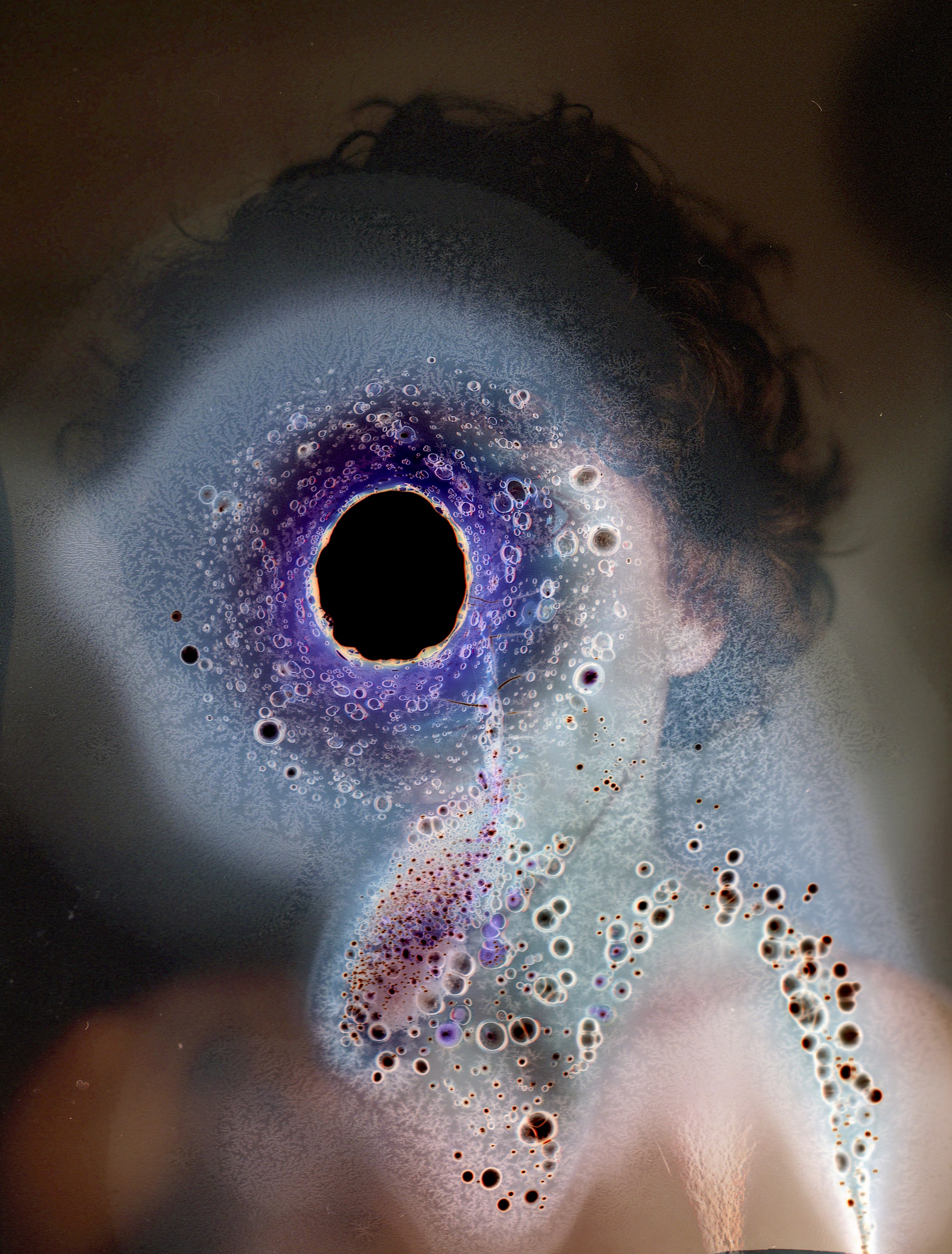

Yes, speaking from what I live, in the first person. That has given me a lot of relief because it takes away that questioning of who I am to tell someone else’s truth. But I also escape from that, because in the end I want it to resonate on a collective level as well. In Neuromantic I look for abstraction. And I’m also going to see what human behavior is like from the outside. I really like that vision of the overview effect: when you see yourself from the outside and get a perspective, like the first time humans saw the earth from space. So yes, from a personal point of view, but I try and want the public to interact with that as well, to live the experience and in turn interact with the project and feed it (for example, by taking part in the survey).

So, after Entre nubes you start doing work in the first person, about yourself or how was that process?

So far I only have two jobs. The second Neuromantic started before I moved in. I gave everything to Entre nubes. The last few years I was in Bogotá, I put my work aside a little bit and I gave everything to that project.

And then I said: ok, in the next project I’m going to look at myself. I always knew that love was an obsession for me. I had the intuition that love could be an addiction and I found some scientific articles that said that, that love acts in the brain as a reward and activates the pleasure centers. In other words, in romantic love, the most initial stage is like a goal that you want to achieve. It’s like being thirsty. It is a super primary desire in the brain and it is something that your body tells you that you need. It is different from when there is an emotional bond later on. That is attachment and it is more related to love and care. It even competes with romantic love, because if there is a lot of it, it becomes very tender and libido is lost.

I was obsessed with that initial romantic love, because all my relationships had been short, intense, highly fantasy relationships with people who were far away or impossible people, or longer but in which I was feeling trapped and codependent. So I wanted to understand why it was like that, what were the psychological, biological reasons and what was happening in the brain, to understand that behavior of mine.

That can reach a lot of people, right?

A lot of people my age the first thing they say to me is like: “wow! I felt super identified, the same thing happens to me ”. There is something interesting there because it also seems to be generational. I mean, all it has become more and more instantaneous, people also get bored easier and we all want that link, but we also reject it.

Another important thing about the project is that I can be the person who becomes obsessed, but it also happened to me many times that I was scared. But then I also want to understand the other, because a lot of pop culture points outward and victimizes us. I want to understand the other person too, that “narcissist”, that “asshole”. There, I started talking with friends who I saw that they followed those same patterns or with whom I myself had gone out and it was like understanding their trip as well. And they told me things like: “I have a hard time connecting with people” or “I need to watch super intense movies to feel something because it is difficult for me to feel” or “what moves me is power and persecution, that is, feel that I have something to achieve and that person is a goal, the more difficult she or he makes it, the better ”or“ I hate when I’m not high because I feel too much ”. But those people are not happy either, they are also going through the same cycle.

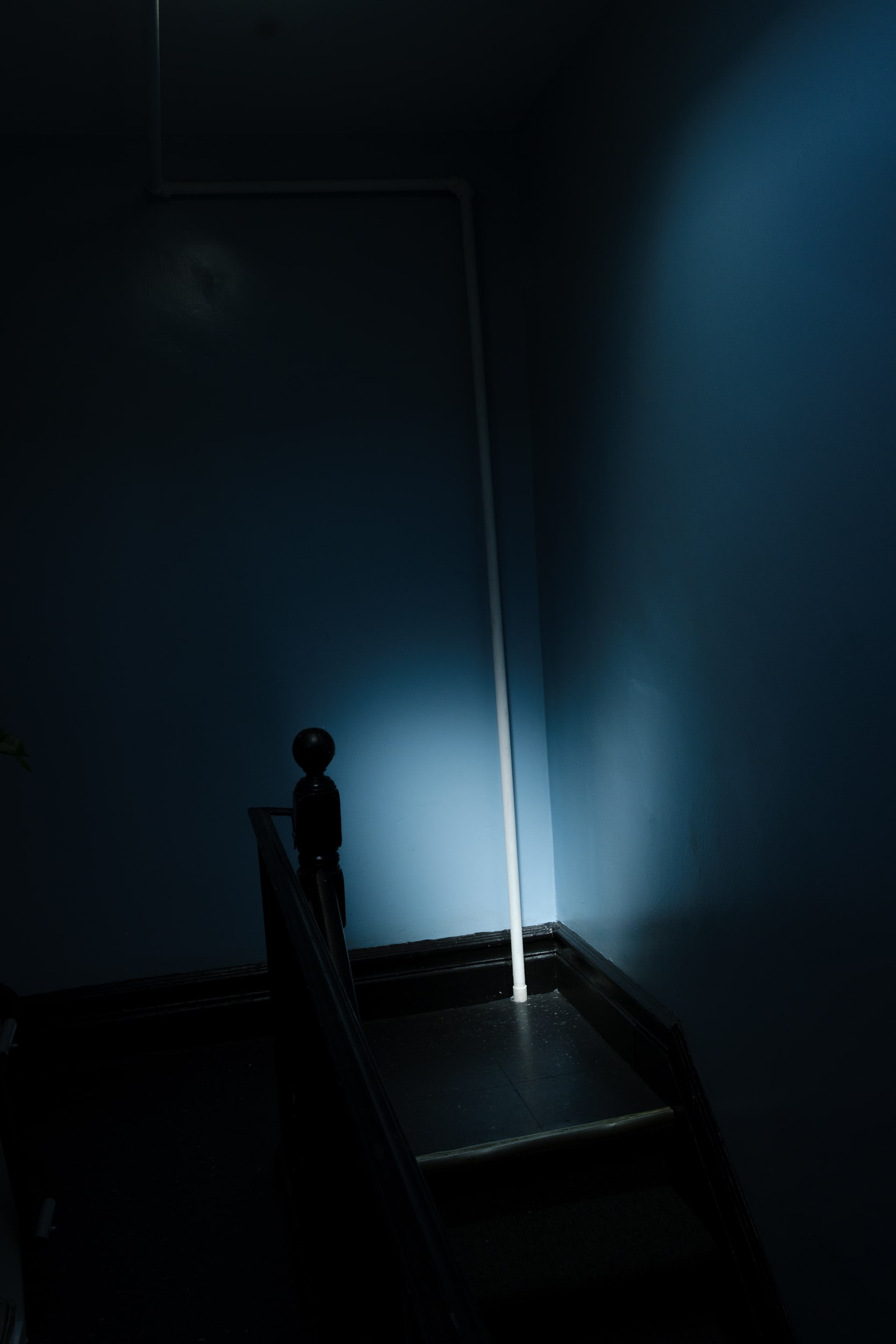

It strikes me that showing this search in photos puts you in a very vulnerable position.

There is a part of my personality that has always been irreverent, I confront and speak about issues that may be uncomfortable for some and I denounce what I consider unfair. But there is a lot of vulnerability here. That is why there comes a point where science appears and I separate myself. I am working with a data scientist and we want to do surveys to see how each person sets attachment styles: there are safe, insecure, anxious and ambivalent styles. It is a quadrant so that we can see how the person behaves in relationships and from that point, how they feel. For me it is super interesting to add that: I feel like this and this is me, but how do others feel? I don’t want the project to be just about me.

Well, it’s a reverse path, let’s say, there are photographers, artists who find a subject and then realize that it really had to do with themselves and they turn it around. Here it is the other way around, you start with yourself to be able to go towards the other.

Yes, one of the things that I realized recently was why to use science to talk about love. A neuroscientist told me: “go read literature or go listen to music. You don’t need science to explain love to you ”. And that questioned me, and I am still in the process of how to integrate art and photography with that data and science. I realized that for me the image has become more and more an intuitive thing, of healing, of processing, of expressing and inquiring. With the project, I have found out about my family and being able to integrate has taken away the burdens that I had carried all my life. At 33 years old, I realized the level of anxiety that I handle and things that I normalized. So the image has become the tool to heal the trauma, but accompanied by that is the science that allows me to get out of myself. The rational part allows me to understand, but both seek to heal.

In that sense, do you think photography allows you to create ties?

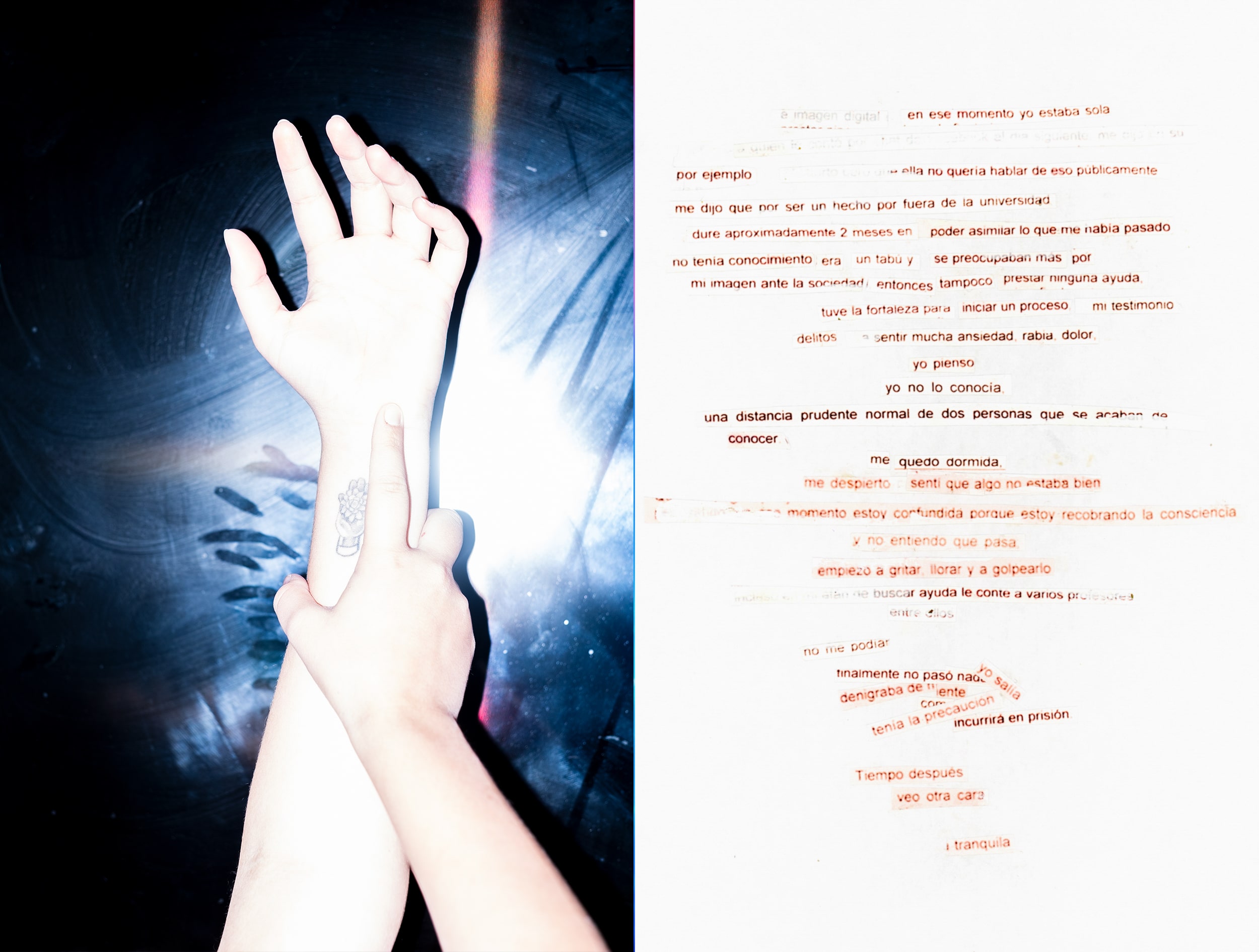

Yes, in the visual part, for example, I started doing self-portraits and the truth is that I did feel very vulnerable there. The people I have photographed have been characters who resonate with my story, who are experiencing similar things, who have similar stories. I photographed my cousin a lot, she and I have been together for 10 years, but we have very similar stories and without a doubt she has also suffered a lot in her love relationships. Also to friends who were going through a heartbreak. So it is a way to connect. Of course, in the visual part, I am in control, there is not so much about them, but rather about my traumas and emotions around intimacy. The men I have photographed, except for one, have been people I have dated.

And they take it easy …

So far, yes. For me it is also part of that process of learning to let go. Usually there are not many people. For example, my cousin, a friend that we were both going through the same thing, another girl with whom I lived here. They are people who know me, we have already talked much more in friendship, there is trust, I suppose. I mean, they have not been strangers. There is a lot of intimacy with these people.

I was thinking that the brain can react in a few ways and have these chemical reactions. But maybe there is something that guides and it is desire, right? There are those who wonder about desire and have come to the conclusion that it is not natural, that it is not only a biological impulse, but that it is something socially constructed.

Yes and without a doubt all consumerism in our society for example, is based on desire. But I would dare to say that if a map of that desire were made, with all its variety of flavors and peculiarities and one could know each person’s and superimpose it, obviously there are different things, but at the macro level they are going to look like a lot. Now, if we go to the details of things, the human differences are infinite, but if we move away we are super similar.

You said that you want the projects to be participatory and you were talking about a survey. How has that worked?

I already made a pilot, and from there 105 responses came out. Now we are going to launch a second pilot because I met a data scientist who works with populations here in New York and we meet weekly. Together we made a more elaborate form in the sense that it will be easier to find correlations and find connections in the data so that there are not only qualitative answers, but also to be able to connect better. Ideally later we are going to present the data in some interesting way so that the public interacts with it.

You learned a photo in Cali and Bogotá. Now that you graduated from the new media program at ICP in the United States, what differences do you find? You said that Latin American photographers are always working on social issues, what is it like in the United States?

In fact I would not say that photographers are doing that, but that everything that is funded and everything that is awarded is that.

New York is super diverse in that sense and it’s cool: here I feel myself in Latin America, it’s full of Latinos. I would say that Americans have a way of looking more disconnected from the subject. In fact, here when they are photographing someone they say my subject, and that for me –and I think for any Latino– is like what are they talking about? Because we intuitively create a bond with the people who are part of our projects.

It seems to me that Latin American photography breaks schemes and that is something with which I identify a lot. We care much more about the concept and telling the story beyond what camera I have or what paper I can print on. We also frequently create from the liminality between the objective and the subjective since magical realism is part of our idiosyncrasy. This together with recursion is fantastic because it leads us to unexpected results and we do it very naturally. It seems incredible, but one arrives here and this is just being assimilated in documentary photography.

Text by: Marcela Vallejo