Ruda Colectiva was born from the encounter and dialogue between two women: Isadora Romero and Mayeli Villalba. They met in Asunción and identified in each other’s stories. Together they began to dream of a collective of women where they could “organize dissatisfaction”. They understood that there were similar situations at the regional level, which in each country had certain nuances. They shared their experiences around the injustices and inequalities they had experienced as women and photographers. And together they imagined a network of support, discussion and personal and professional development.

That dream is now shared and lived by eleven photographers from eleven Latin American countries. Isadora Romero (Ecuador), Mayeli Villalba (Paraguay), Luján Agusti (Argentina), Koral Carballo (Mexico), Gabi Portilho (Brazil), Wara Vargas (Bolivia), Fabiola Ferrero (Venezuela), Ximena Vázquez (Colombia), Ángela Ponce (Peru), Morena Pérez Joachin (Guatemala) and Paz Olivares Droguet (Chile), make up Ruda Colectiva.

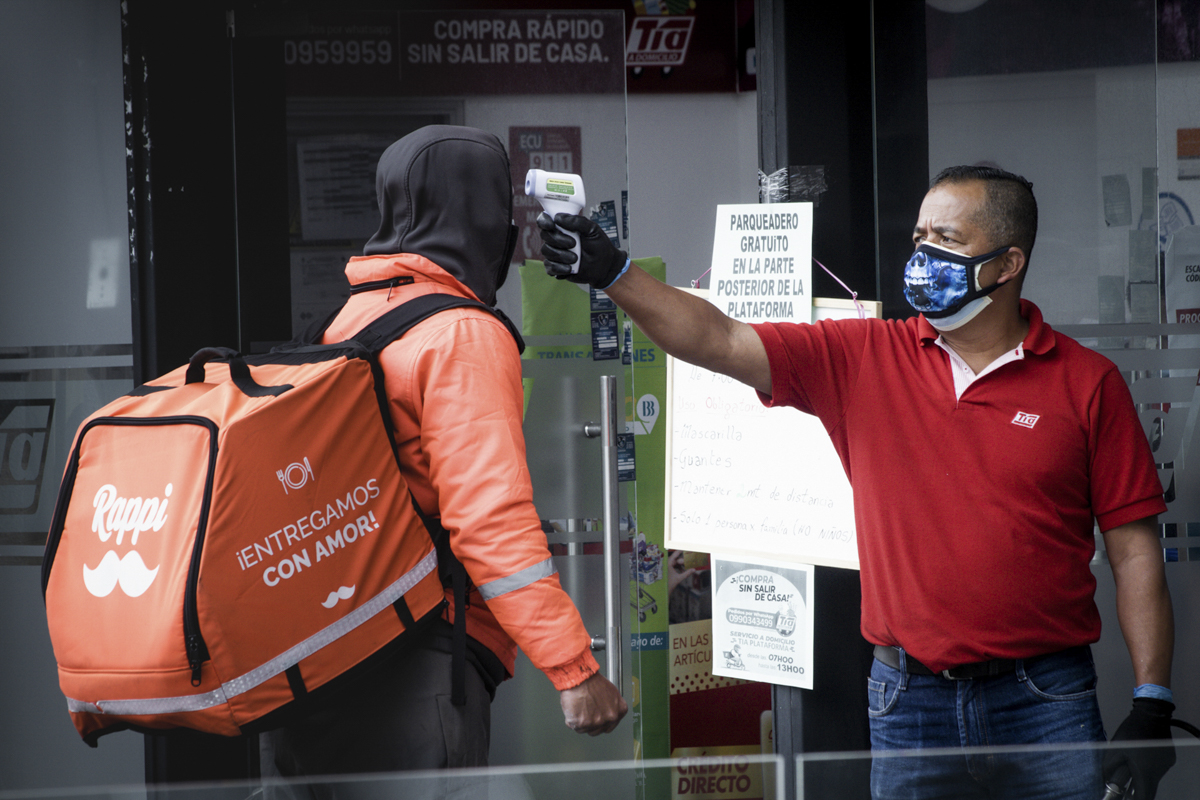

Today, March 11, 2021, they launched the website of their first collective project: Esto no es una cadena (This is not a chain). They started it during the mandatory confinement due to the Covid-19 pandemic. The photographers wondered: what could not stop, at a time when apparently everything had stopped. The answer led them to reflect on the relationship that as humans we have with food, the different ways of producing and consuming it. With the support of National Geographic, each one in their own way and in their country told a story related to the subject.

A year after it started, the project was transformed, and today a website is launched that not only has photographs and texts, but also audios and videos. All told from the diversity of views, ways of approaching the issues, narratives and territories.

Mayeli Villaba: Currently we are 11 members of the Collective, each one is from a different country in Latin America. Two people first dreamed of this wonderful project that Ruda became: Isadora, our partner from Ecuador and me, from Paraguay. We had the opportunity to meet personally a few years ago at a photographic event here in Asunción and we realized the super unjust realities in relation to women and colonialism in general that existed in our territories. We realized that the realities of our neighboring border countries were also very similar and we concluded that this is obviously a regional issue, it is not something isolated.

We began to dream from there: how to organize a little more the disagreement we feel in relation to those unfair realities that have to do with machismo within the work environment, the professional environment of photography and also the storytelling in general. In other words, how we feel being workers in photography and documentary, and how we feel when we read our stories always told from the same pla

There we began to dream of a cross-border collective, which would give us the possibility to know what is happening in the region, to propose narratives from that other point of view and which would be a space that allows us to generate the opportunities that historically were denied us from telling the stories. So we started inviting colleagues and we became 11, which really is a lot for the daily logistical organization.

Now it has a life of its own, it no longer depends on Isa and me. We only threw the first stone and now it is a collective space in which each one is indispensable and fulfills a super important function. And it is being reconfigured, of course, like any collective and long-term process.

Fabiola Ferrero: we have very different backgrounds. Ruda is a group where you constantly learn not only from the country, but from the life experience of the others. I think that this process is very nourishing when we question ourselves from where we narrate. And I think that’s a central question, where do we stand from? Not only geographically, but in terms of our own story and how we want to tell it.

Gabi Portilho: this diversity is very important, because sometimes we think of the community from the point of making something uniform and I think it is a way to even come into contact, to enter into friction and rubbing, we do not always agree. We have different points of view, different languages. There is no uniformity, but things come from there. I think it is a very important part of the community: diversity.

Why did you choose Ruda’s name?

Mayeli: We thought a lot about what element could characterize us at a regional level. At that time Isa was working on a project that had to do with the production of the land and I was working with her. So we were super connected with the theme of the land, nature, ecology, production and respect for nature and the ancestral connection. We started to see all the names that had to do with it. We think of corn, for example, which is something that is present in many of our Latin American cultures.

We came up with Ruda (Rue) because it is a plant that represents us a lot due to the healing properties it has, it is a natural element. And also because there are many tricks that are made with it since ancient times to heal, from physical health issues to spiritual issues. It also has a very provocative name and putting it next to collective we think it seemed like a statement itself.

“I don’t believe that any sector can be included in a single representation”

The collective is made up only by women. Do you believe that there is a female photograph, of woman, or an exclusive look of women?

Mayeli: I don’t think that any sector can be included in a single representation. The title woman in the singular can be limiting and exclusive because we are so different, there are so many ways of being a woman. Starting with the most obvious: we are cis women and there are other ways of being women that have nothing to do with sex, with the association between sex and behavior assigned from birth. I mean, there are millions of ways to be a woman. Millions of life experiences. And creation has to do with that, it is directly linked to the experience of life and the subjectivity of people. Science and positivism always wanted us to believe that we could not involve subjectivity and that everything had to be in the third person and so on. In fact, we always create from our own experience from how we see the world and that is crossed with one’s own subjectivity.

So, it doesn’t seem to me that there can be a way to encompass a woman’s gaze in the singular. It can be so diverse that we are not even aware of it. But, what I do believe is that it is a very large sector of the world population, which has always been relegated from the possibility of occupying spaces in narratives and in everything that is representativity, from whatever point of view you see, It is unfair. It cannot be that there are so many people in the world and that we do not have access to being able to propose, do things and be recognized for what we do. Or in the economic and professional case that we do not receive payment for the work we do.

I want to speak from there, from the right we have as people to be able to tell about our life experience. Obviously sex and gender assign you different experiences and places in the world and that will mark your narrative.

Gabi: I don’t think of a feminine aesthetic either, I don’t think so. But I do believe that there are issues that cross us as vital issues, which sometimes do not happen to men. For example, I see in many collectives that healing, ancestry, motherhood, sexual violence are topics that appear frequently because, I believe, that in some way those are topics that cross us. It is not that we have to restrict ourselves to them, of course, but I speak of a need perhaps to heal wounds that we have inherited for so many years. I do not see this as a language of female photography, but rather as themes that are perhaps very latent for us. So there is a common look in a certain way.

Fabiola: There are people who tend to think that men photograph in a more violent, more direct way and women are more sensitive and I don’t see that either. Today I believe there is an important expansion of photography, especially in Latin America, I think that question of how we narrate ourselves without imitating the vision to which we have been exposed for so many years, which was not that of our own eyes. In that it is very present, regardless of whether you are a man or a woman.

Mayeli: We usually talk about this also in our everyday conversations. And it is very important to keep in mind that not because you are a woman you are going to have a feminist narrative, for example. That is something that tends to be very directly related and naturalized. It is as if she is a woman, then she is going to be critical of the patriarchy or she is going to have a critical look at gender inequality and actually it is not like that. Feminism and criticism of patriarchy are political issues that a person has to develop in order to build a position. Of course, you don’t have to develop anything to be beaten down by the unequal system. You may be the victim of an unequal system, but not be critical of it.

A permanent effort is how we propose something else if we were educated from a very specific perspective. Not only the school where you learn photo narrative, but also television and all the mass media that always educated us in a sexist and racist discourse. So how do you get out of it when it’s your turn to create?

Fabiola: Also, although the woman is more active in these types of issues, she does not have to limit herself to these issues. Women can also have an opinion on global issues. Many times it is assumed that the man is the one who covers the global event and the woman focuses on what the women think of this global event.

Gabi: Sometimes I feel that this limitation comes more from the editors than from us. During the beginning of the pandemic, for example, much of the coverage in the world was done by male photographers, not female photographers. And this happens frequently with subjects considered more “prestigious” within photojournalism. It is a choice that does not always come from us, but rather from an imaginary that still says where women should be, what topics correspond to us or what spaces we should occupy, even within photography.

The relationship with the industry is a very interesting topic and is not always discussed. Is there a pressure or how is this relationship with external agents to produce and work on certain issues?

Fabiola: There is that pressure, but at the same time I think there is a custom of what we think is Latin America. But right now there is this search to try to cover other things that are not the Latin American clichés. It is nothing more than violence, poverty, Latin America is such an infinitely rich territory in so many things. And I see that search very present today, especially by new generations who are trying to focus their gaze the other way.

And more than talking about ourselves, it is really knowing what you can have the property to touch on a certain topic. In other words, it seems to me that there are topics that I don’t get into because I don’t have the training to talk about it.

That makes us think about positionality, about an awareness of the place we occupy, from which we enunciate and how we relate from there.

Mayeli: Especially if the discourse that you are going to construct is going to have a lot of diffusion and is going to create imaginary in relation to the people you are talking about or the problems you are addressing. It is an ethical question and historically relegated. But now we can no longer continue to be those who do not know this, there is no way.

Gabi: There is something that bothers me and it is this idea that we have to narrate within some issues that are “Latin American issues”, what is that? When you look at European photography, for example, they talk about everything, they talk about life, subjectivities, intimacy, everything. And here it seems to me that we always have to narrate specific themes.

Our mission as a collective is to break a bit with these places. In the case of It is not a chain, our project, why do we have to narrate nutrition only from a certain point of view, or with a certain language? That keep me thinking a lot while doing the project. How can food be narrated from a point of view that is not just documentary? Hunger is a super important issue, but other issues are also there.

I think we have to make this effort at this time, understand how we want to build these narratives, and discuss them from the community.

When you say that Ruda is a cross-border collective, do you refer only to territorial borders?

Mayeli: The territory is super important, but we share many questions about the cultural aspects of our countries and how we live a problem that is present in all territories, but has its variants. We are always talking about our identities, during the elaboration and development of this project we talked a lot about how capitalism is lived in the food sector.

Why is this called This is not a chain?

Mayeli: Precisely because what we do is criticize that supposed linearity of the hegemonic discourse, where there is a food chain that is supposed to have a logical and unbreakable order. This discourse assumes that food reaches everyone, and that when someone has a place within that chain, he cannot move. That is, if you were born a consumer, you have to die a consumer and not consider producing your food.

How did the idea come about and how was it developed?

Mayeli: Gabi had a dream.

Gabi: When we were in the development phase of the project, we did not know how we would do it and it came to me in a dream that it was not like a chain, that we should not imagine a chain. Here we talk first about the food chain. Biologically speaking of the human at the top of the chain and how that impacts everything: the idea of what we eat, of the rights we have over the things we eat.

And also the idea of a production chain, because today we are trapped: if supermarkets close, we don’t know what to do, we would starve. The title might be It shouldn’t be a string.

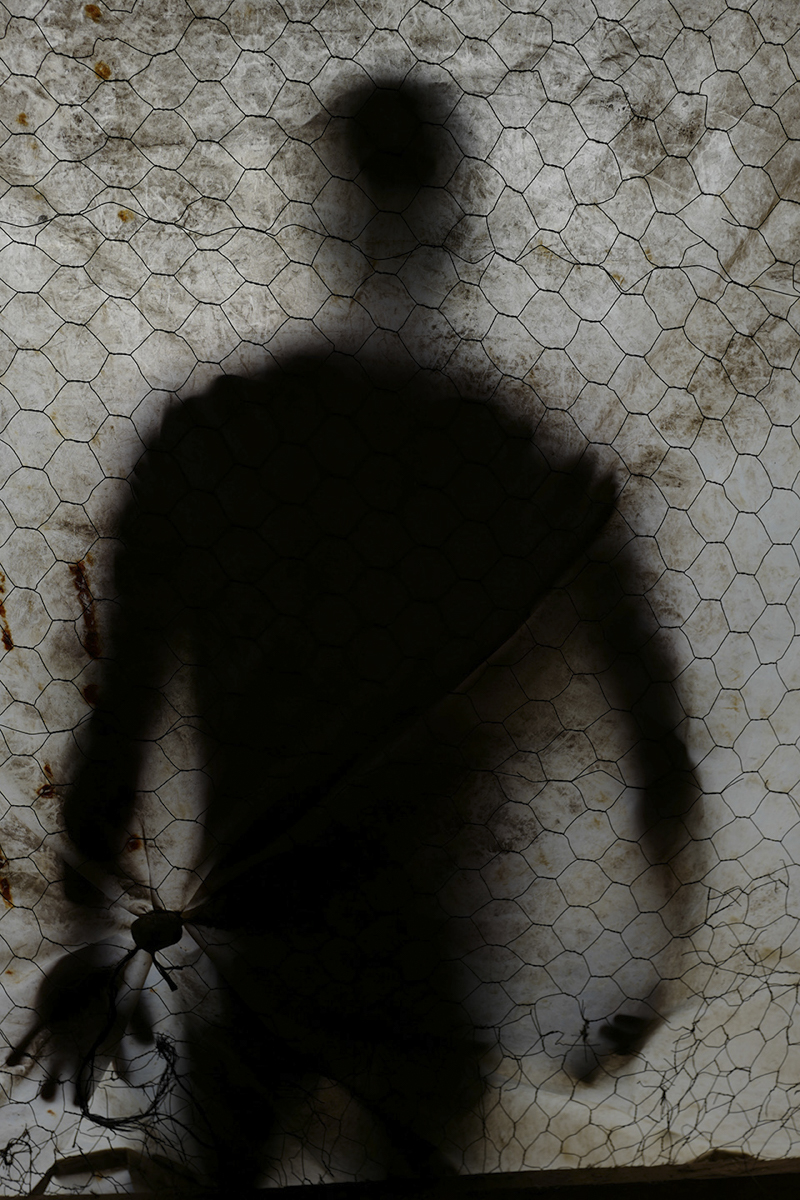

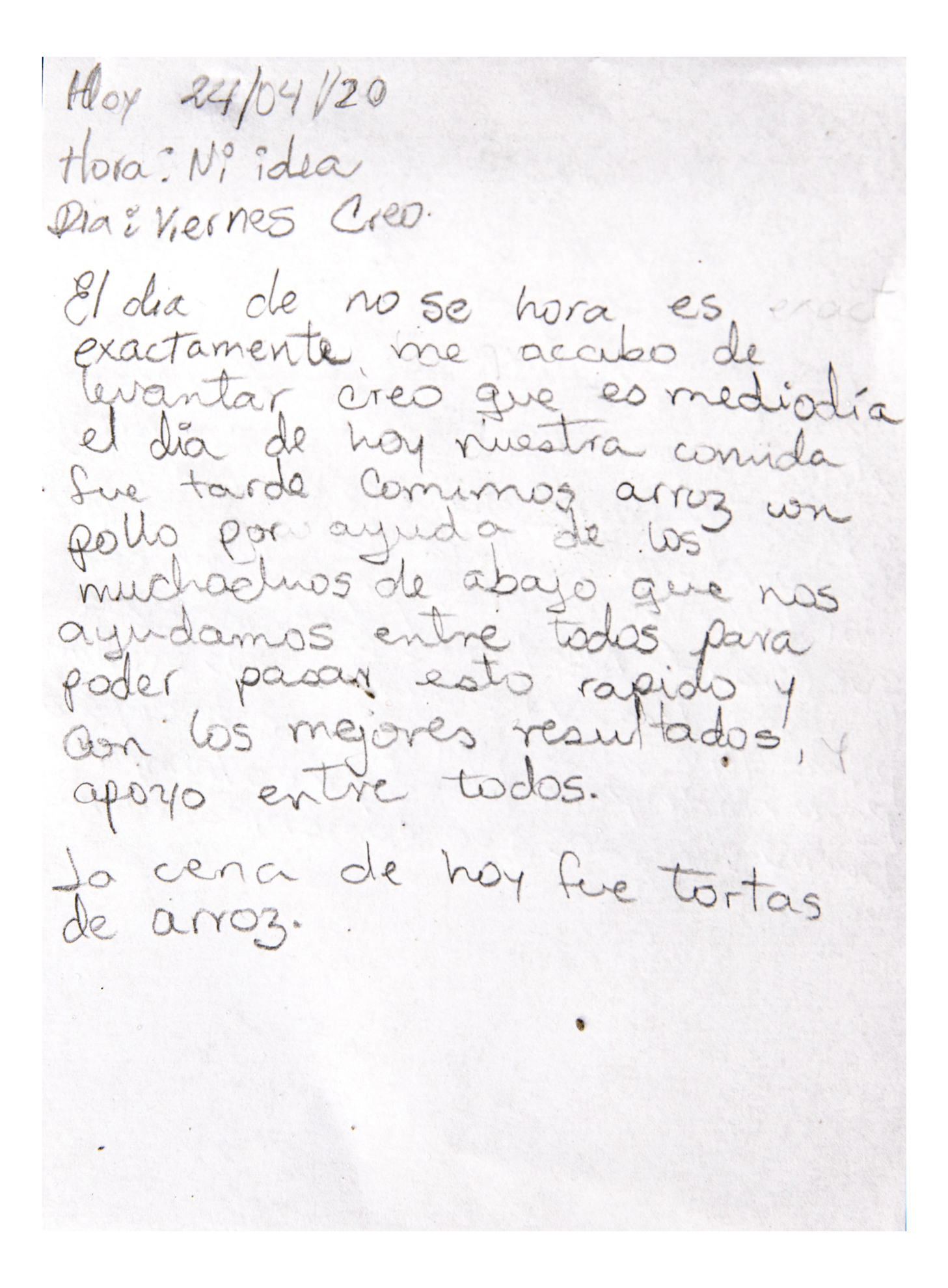

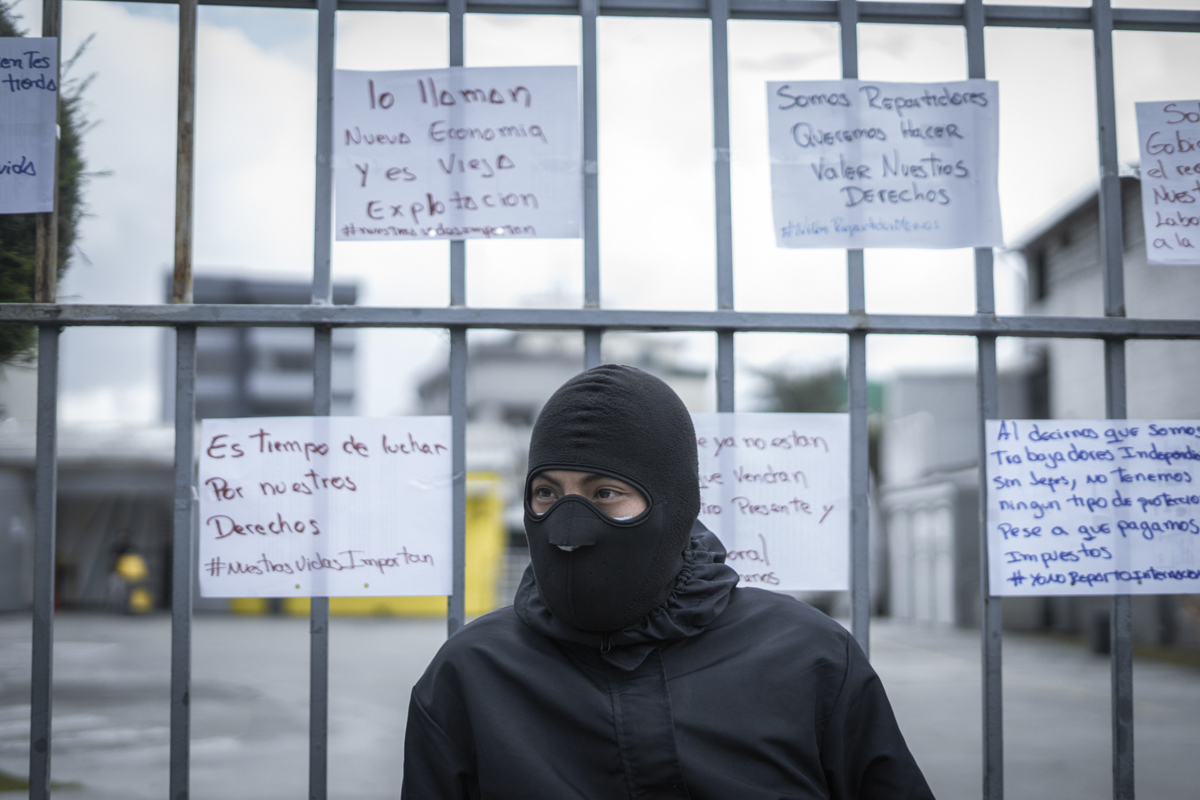

The idea was started because just when everything stopped we thought of something that could never stop. We can’t stop eating. From there we think about how to talk about these territories not only physically, but also from other different aspects: the question of employment, as Isa speaks with the delivery people or from a more intimate question, rural or urban.

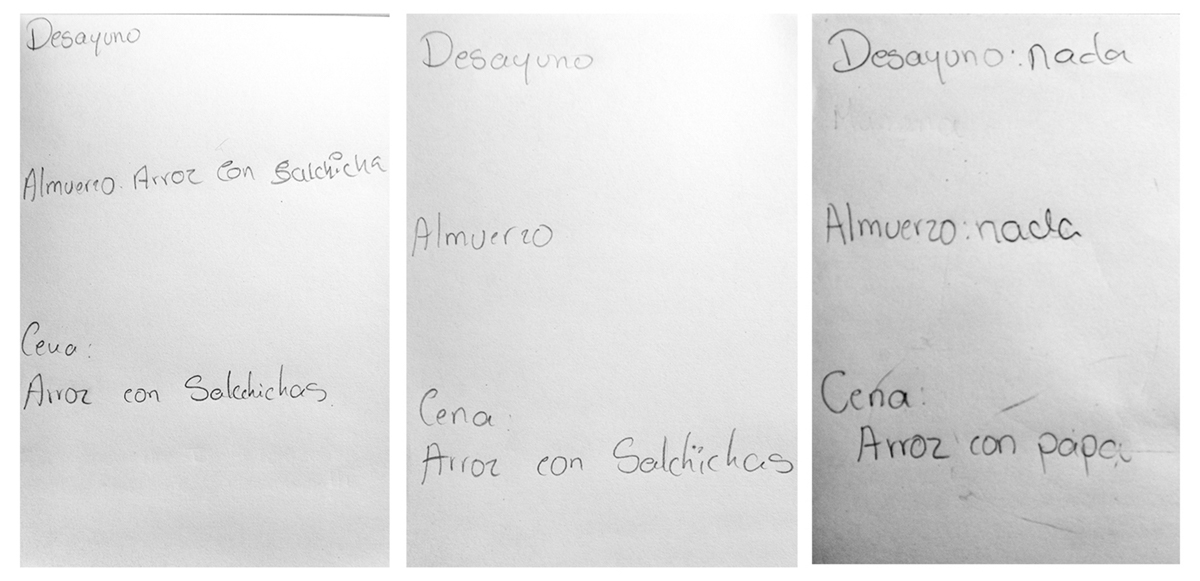

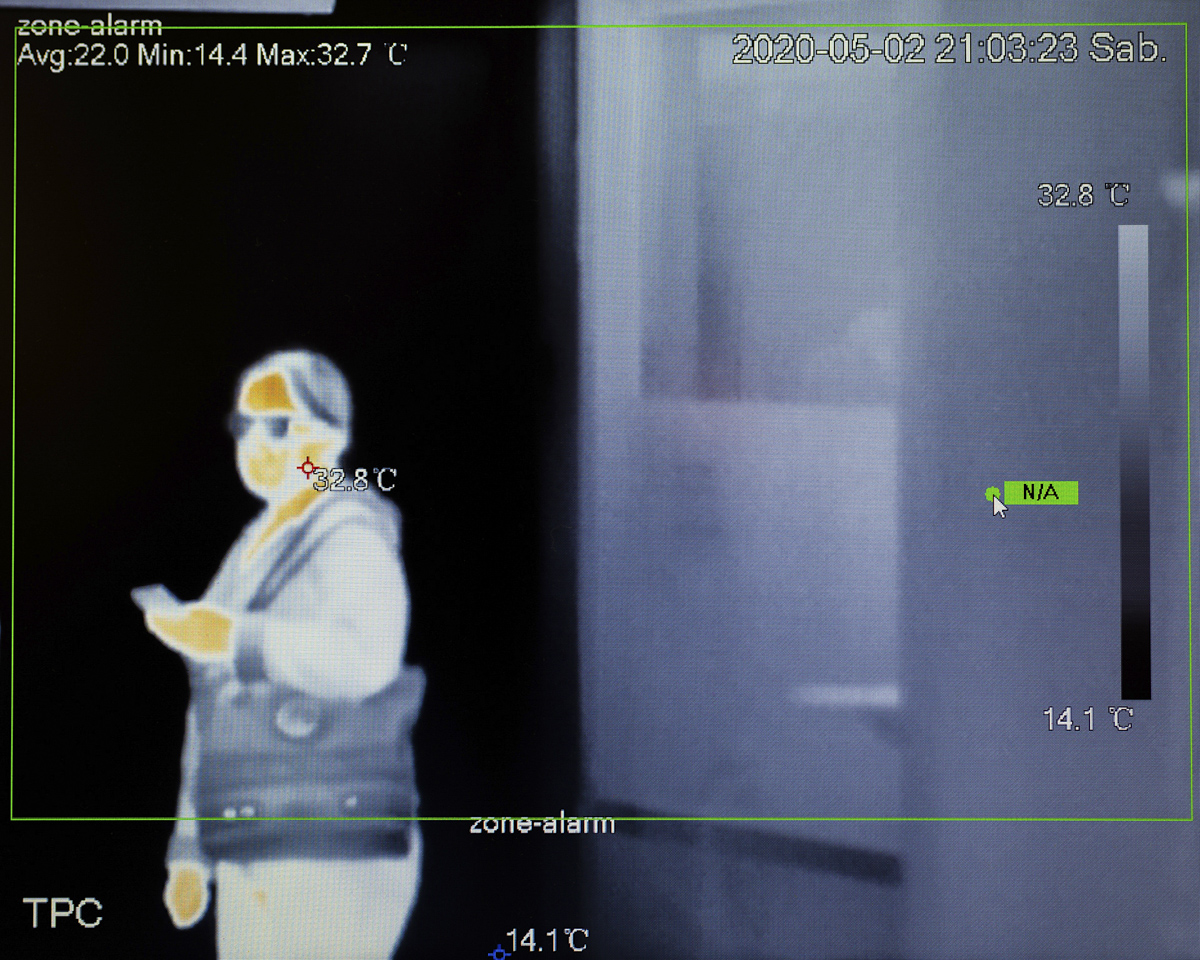

Fabiola: At the beginning of the pandemic we met every friday to give each other support during the confinement. And in those conversations the issue arose of how the pandemic was exacerbating differences that already exist, this pandemic does not show anything new, it just exaggerates it and puts it more in your face. Speaking of which, we all began to notice how in each country, food was becoming the central concern of the people.

We detected that this was going to be the central theme in the following months. Many people said: “If I don’t die of covid, I starve to death.”

“If I don’t die of covid, I starve to death.”

How did each one define what they were going to work on and how did they manage to put everything in dialogue?

Mayeli: This is the first project that we are developing simultaneously and collectively. It was a super nice process to meet us from there. It did me a lot of good because it was very challenging, but at the same time it was what got me out of bed in a moment of emotional paralysis. We were more or less all in one situation. As Fabi says, we got together religiously every Friday and each one was choosing the topic that seemed most interesting to narrate from our own particular interest, something that had to do with ourselves and that was feasible, because it was a super complicated moment.

Some who needed permissions stamped by state institutions to be able to leave and we were pending on what was the last recommended security equipment to leave the house and not put anyone at risk.

Gabi: In my case I started to count from my personal experience. When we decided on the issue, here in São Paulo everything was closed and in my neighborhood, for example, people were super aggressive with the ones who went out. So I decided that I was going to narrate from the intimacy of my home

It is super difficult to narrate from the collective. And it is more difficult because we are in the middle of the pandemic. We are 11 photographers from different territories and everything has to be done virtually. In this first project, more than the final result, the contact has generated the ideas that come out in this collective process, is very important. That is most important, because we are very used to a life of individuality since we were little girls. Leaving the individuality and leaving for the collective is super challenging but very rich, very important, it opens us like many portals.

When a project is proposed, one imagines something, but the process transforms it. How did the project change the time that has elapsed?

Isadora Romero: It has undergone a lot of transformations because being stories that were born from a personal interest, the challenge was to find that collective anchor. It was one of the biggest challenges to see how to fit the looks and the way of approaching each one within a collective story. Finally, we accepted that we did not need to homogenize the stories and that our gazes were confused and diluted. But rather highlight the diversity.

Once we were compliant with National Geographic, we entered a slightly freer process of seeing how we wanted to transform the narrative form and where we wanted to turn it. That was another twist. The beauty of the web is that it allows us to include multimedia, videos, and wonderful audios. That allowed us to incorporate a lot of other things that were not contemplated in the initial project for the grant and that perhaps were born in a more free way.

Text by: Marcela Vallejo