The green that inhabits my dreams

Adriano Machado is a visual artist of African descent who lives in a small town in Bahia, Brazil. His photographs come from what he calls “Afro Inventive territories”: images that seek to reorder the politics of life-based on respect and dignity. In his Contos Fotográficos, he interweaves three series of portraits with three written stories to rethink death, life, freedom, and fantasy.

Adriano Machado still hears the voice of his maternal grandmother. A few years ago, while preparing his thesis on visual arts, she told him that a disturbing animal invaded her dream: a green snake, “a beautiful green, a color I don’t know how to describe.” The next day, her grandmother went to work at the market and thought she should buy a house. At that moment, a person arrived and offered her a piece of land. She did not hesitate: she agreed and purchased the property. The dream, for her, was a sign. “Dreaming green is always a good thing,” her mother had told Adriano.

For Machado, that personal story, at once so quotidian and so fantastic, forever changed his way of thinking and doing photography. Thus, in 2014, Cobra Verde was born, the first of a series of works related to memory and fiction, identity, and family ties. Machado consistently portrays relatives of his own, as he finds it challenging to photograph people with whom he has no trust or affection. He opposes the idea of simply capturing photos: he constructs images that give body to the reality and fiction surrounding his daily life. As in the stories and dreams, his grandmother told him.

As a child, Machado wanted to be a writer. He thought he didn’t draw well so he couldn’t be any other kind of artist. It wasn’t until college that Machado discovered the potential of images, especially photography, to create narratives. Since his university studies, he has been interested in the concept of still life. In his search, he began his project Estudos Sobre Natureza-morta, which later led towards the construction of the Contos Fotográficos: three series of portraits intertwined with three written stories. Neither the text explains the image nor the image illustrates the text: instead, they dialogue and together create new narratives. Machado calls them “Afro Inventive territories.”

“They are the poetic places where my images exist. It is as if they come from observing those territories invented or created by the Afro-descendant diasporas that inhabit this indigenous territory called Brazil.” For Machado, this creative gesture has to do with the ways of existing, with how black people construct life. In that space, he says, poetry is closer.

The works in which you include your relatives begin with Cobra Verde. What is that project about?

Cobra Verde arose from the need to tell the story of my family. While researching, I interviewed my grandmothers, and from what we talked about, I began to imagine and build images that embrace both sides of the family and mix them.

I am interested in telling the story of two women who survived, struggled, and built a family in the territory that is Feira de Santana, a city in the interior of Bahia, which arose from a free market built at the meeting of fundamental roads for the cattle trade. My maternal grandmother was a saleswoman in the market. My paternal grandmother was a washerwoman. She passed away when I was 15 years old. In telling the story of a person no longer around, I learned that one could narrate from other people, so I came to my aunt. I find it beautiful to think of time beyond a body, how narrative traverses voices and people come to me in a movement that breaks with the idea of death.

The stories of my grandmothers have points in common: they are both black Bahian women who struggled to survive and raise their families, despite their complex love relationships. Women had to be heads of households when men were absent. And who built solid foundations related to faith, work, and a collective survival structure. For example, my grandmother talked about the importance of being willing to help a neighbor and taking pride in one’s work.

The project tells the story of the dream your grandmother told you, which was later reaffirmed by what your mom said about what it means to dream of the color green. How do dreams and imagination intertwine in your photos?

The images that make up Cobra Verde are diverse and have a foot in fiction, in that place that we can’t handle, although it exists and is accurate. There are fantastic stories, like when my great-grandfather threw coal on the floor and made a circle of fire, forcing the women to stay home, and my grandmother fought to get out. As she was telling the story, my mom interrupted to say the same story in an even more fantastic way.

That is the territory of reality, which is also traversed by silence, an essential point for my work. My grandmothers told their stories, and sometimes they were silent because what they were going to suggest would transport them to a powerful place of affective memory. To remember a person is, in a way, to bring them back.

In addition to your grandmothers, aunts, and mother, you have taken many photos with your cousins. You can see how their bodies change over time. Why is it important to involve your relatives in creating the images?

Since Cobra Verde, I decided to construct the images with my cousins. It became almost like an ongoing procedure, and now most of my projects only involve my relatives or people with whom I have effective proximity.

That’s not to say that I need intimacy, but I do need trust. When I portray someone, that person delivers something that is him or herself to a story I am building. People need to be comfortable in that imagination. I’m not interested in the photographic process of a simple capturing movement.

That doesn’t mean that my work is collaborative either. I know I am an artist; I have the camera and propose the image. But all these ideas are intertwined with our coexistence, and that’s why they have that naturalness.

“How do you portray black people? It’s a question I always carry with me. What I do has a direct relationship with people of my intimacy. For me, it is important to build images with them that point to a place of respect, dignity and not a place of capture.”

Do all the images maintain that idea of coexistence and shared reality?

Yes, for example, in Baratino, which is part of the Contos Fotográficos, I constructed some photographs that portray my cousin holding an animal. They are animals he lives with, and that is directly related to the place he lives in. The idea is to mix those places to create intense images. I like to think of creating a territory of elements of a certain beauty, which have something that will silently penetrate the mind of whoever sees the image, and there, something will germinate.

I think about that because some people feel there is something in the photos that they can’t see. Others have told me that my images are strange. I like that because it’s like I could build a subtle game where the ideas and the intention slide through the vision and silently reach the people. The layers of interpretation settle and remain in the people and then sprout.

With Cobra Verde, you graduated as a visual artist. Then you continued your work and united some of them in the project Contos Fotográficos that you presented to the master’s program. Where did this idea come from?

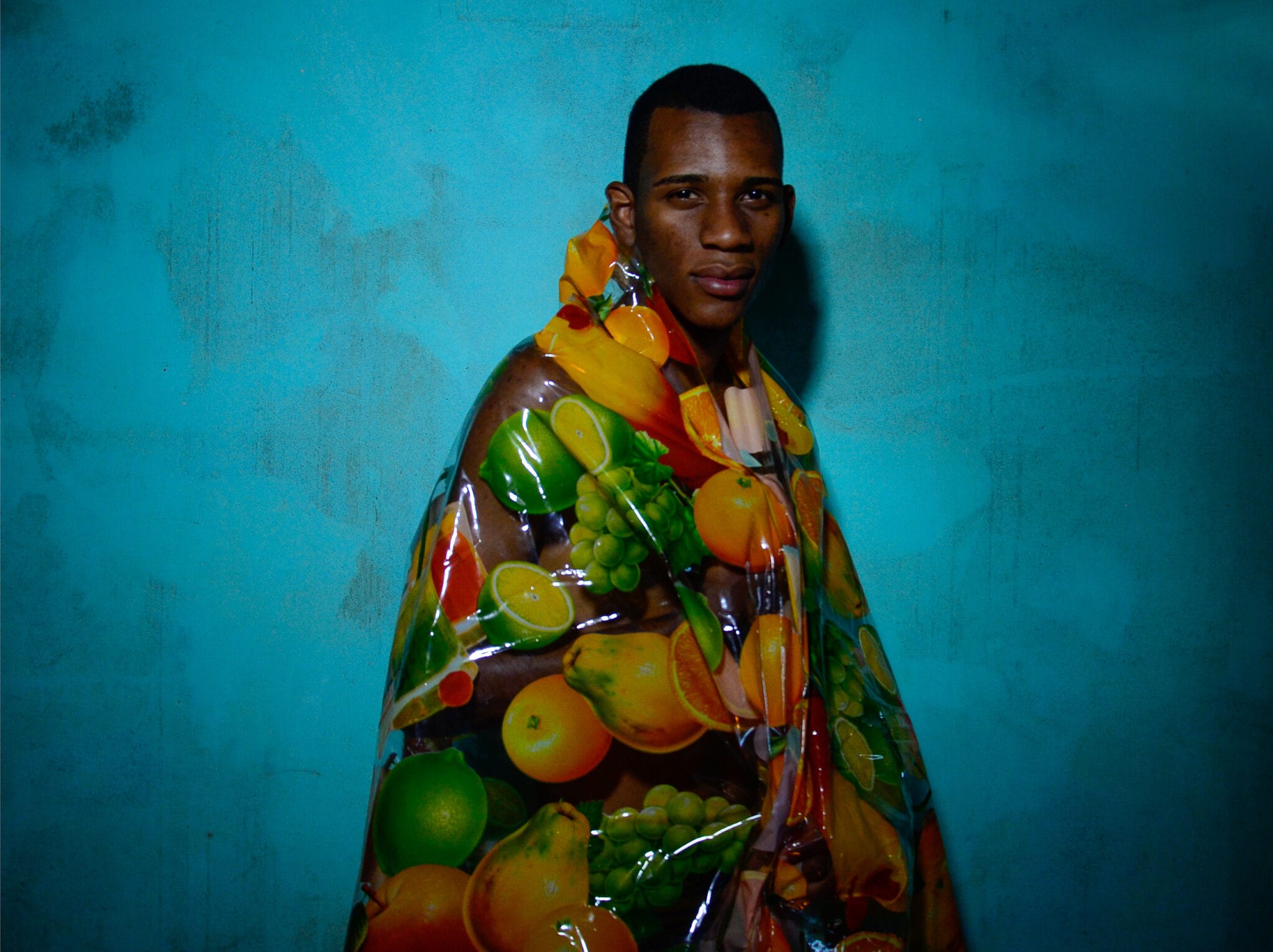

Contos are a development of my research Estudos Sobre Natureza-morta that I’ve been working on since 2015. I started by making those images in which I covered my cousin with a plastic tablecloth with a fruit print. From the still-life paintings, it strikes me that putting fruits, animals, and things on a table brings the idea of a time in suspension. It also has a touch of realism that interests me and is close to photographic work.

I wanted to create a tension between portrait and still life to build a place from which to launch a critique: a black body in the history of art. This reorders the notion of portrait and, at the same time, plays with words: in English, it is still life, that is, life in suspension, paralyzed life. It is an image without time, where life is like escaping from the end. That makes me think a lot about the construction of images of black people. If you don’t give an end to these people, then you are building a powerful place, an eternal place.

From those Estudos Sobre Natureza-morta you build three stories. What are they about?

The first one is called The Child (O Menino), and in it, I present the work Lugares in which I make still lifes in front of a mirror in my room. It arises from observing my daily life, which allows me to understand time. In the images appear things from my everyday life: a sandal and a belt. I begin to think about the fiction of that world through a mirror, of the possible layers of the image in my work.

Then I begin to write about being a child who is discovering the photographic task, and as he finds the construction of the image, he discovers the world. These stories maintain the idea of mixing times and constructing new images with the texts. They are two intersecting works: the text does not explain the photo, and the picture does not explain the text, but they are intertwine.

The second story is O Rapaz and the accompanying photos are from the Baratino series in which your cousin’s eyes are covered with different materials. In each image, he holds another animal. What did you think of this story?

In this story, I am dealing with different issues, from thinking about death when it appears and crosses us to thinking about the violence that we also live in. I am interested in thinking about tension. The animals that appear in the images have different meanings. They are animals that we raise, often as pets, but also as food. It is as if their lives are suspended on a threshold, the tenuous line between being alive and dead.

The thing that covers my cousin’s eyes is always something that creates a third layer of intention in the narrative. These are things I’ve been collecting. I’m an artist who assembles things, so when I’m walking the streets, I see things, manage them and keep them. I think that they will later have some meaning in something I’m thinking about or will later think about.

What does ‘Baratino’ mean?

Baratino is a Bahian expression for lies. Someone may say “você tá de baratino comigo” when I tell an absurd story. It’s like saying: you are lying. I like that word because I play with these layers of fiction and reality in constructing the fantastic. The photos organize my daily life and that of my family in a place that allows people to see themselves. But it also opens up layers for them to add their baratinos to the story.

It also touches on tense issues: framing and cropping the image of a black person denotes a violent place for me. Framing is like reducing, cutting the person, immobilizing them in that place. The images revolve around how violence is organized around us and how we try to get out of those places. In Baratino, I tried to express some questions, for example, about the tradition of photographing black people in Bahia.

Black people have often been in the place of the observed. How can this approach be changed through photography?

How to photograph people in Bahia and portray black people are questions I always have with me and run throughout my work. What I do has a direct relationship with people of my intimacy. But it is always a point to think about how to construct images of others. For me, it is essential to make images that point to a place of respect and dignity and not to a place of capture.

To talk about the possibility of walking freely in the world, I make the third story, Orimar. It is a work in which I print portraits on transparencies and attach them with nails to a landscape on the wall. At the same time that the picture is attached to the wall, it is loose in the air. That game helps me think about freedom, how to flow through the world, and how the image can do that. Transparency, printing, and development are part of photographic knowledge, and I like to think of them as an expansion of methods.

Among the things you have published are some photos accompanying an article by Ariella Aïsha Azoulay. She talks about art as part of the collective construction of the world and not as an individual creation. Do you consider yourself an artist who contributes to constructing the world in which you live?

The artist is a worker. It is necessary that artists assume themselves more as workers and not as geniuses. The construction and artistic training is still based on the idea that an artist is a person who was born with a gift and can create incredible things only from his desire. As if he were an innocent person in the world that the only thing he does is to make.

It is not enough to continue thinking of artists as beings disconnected from time, the world, and the intentions behind them. Images are not innocent, they are not disconnected from what is happening. Artistic work is a tool for the production and destruction of worlds. The camera itself is a weapon: we shoot, take pictures, and capture images.

I like a phrase from Macaco Bong: “Artista igual pedreiro”. The artist is equal to the worker. If we think, for example, of the artists of my generation, none of them have received inheritances. Most of us come from the lower classes. Now there are many artists who, to become artists, went through many difficulties. They come from places where there are no financial reserves to dedicate themselves to art.

There are indigenous communities that, for a long time, refused to be photographed because they believed this type of image stole their soul to some extent. With photographers like Cinthya Santos Briones we have asked ourselves to whom do the images belong, to whom do they belong or to who appears in them?

To not worry about who the owner is, I believe the images should be born from an encounter. For example: who owns the photo album in your house? There are images of your parent’s marriage, your sister’s birthday, and a barbecue in the backyard with the whole family. Whose pictures are they? They were built in an environment of trust, consensus, and dialogue. From that place, ownership is annulled because images are the materiality of the encounter and the relationship.

It is very different when it is a capture, and what is done is to cage something. There the image becomes a thing, a property that needs an owner. We cannot think only poetically because we have the whole issue of the art circuit and the market. But, for example, in the case of Claudia Andujar, who has been photographing the Yanomami for a long time, whose photos are they? Claudia Andujar and Yanomami. There is a relationship, and there is trust.

If we think of situations as objects and relate to people as if they were things, then the images we make will also be that and will need an owner and a property.