What can this fruit tell us about Latin America?

Juanita Solano, a Colombian curator and expert in art history and photography, tells us about La fiebre del banano, a digital exhibition that brings together 100 works by Latin American artists on the world’s most popular fruit: a metaphor that reveals the structures of violence that shape Latin American identity.

Taken from high above, with a drone’s eye, the image shows an extensive plantation on the Ecuadorian coast. Nothing would catch our attention if it weren’t for the fact that we can make out a little golden dot in the middle of all that intense green. See it?

In a second photo of the same plantation, but this time taken very closely, we will know what it is: a vast banana plant plated in gold, the same coating used in the religious works of the colonial churches.

The artist María José Argenzio, author of this work, gave it an unusual name: 3° 16′ 0″ S, 79° 58′ 0″ W. These are the coordinates of the site where that golden plant is located, some remote place in the coastal province of El Oro, in southern Ecuador, the country that exports the most bananas to the world. Argenzio’s gaze brings into play the two products that have been most exploited in his country: gold and bananas. But above all, it condenses, in a powerful gesture, the extraction processes that still cross our continent.

Like this piece, the virtual exhibition La Fiebre del Banano (Banana Craze) gathers 100 works by Latin American artists around this fruit, from 1960 to the present. Colombian art historian and curator Juanita Solano says that, together with her colleague Blanca Sierra, she started this reflection thinking about “the role of fruits in the geopolitical relations between the global south and north, the construction of colonial realities that still remain, and the possibilities that a fruit like the banana offers to understand the recent history of Latin American nations.”

Bananas are today the most consumed fruit on the planet. Its production reaches 116 million tons (enough to fill four million containers), and its export produces about 12 billion dollars yearly. It is not native to the Americas, but its cultivation is so widespread that it is the most widely produced fruit in Latin America and the Caribbean. Not surprisingly, since it began to be cultivated, the banana has been part of the global visual culture. In the Americas, its first representations date back to colonial times. And from the second half of the 20th century onwards, numerous artists from the continent began to reflect on the importance of this fruit in the global diet and its role in contemporary history.

Hence, for Juanita Solano (who co-directs at the Universidad de Los Andes a research group on photography activating the BADAC archives and a study on women photographers, especially on the Frente Fotográfico, one of the first collectives of women photographers in her country), La Fiebre del Banano exposes through art the effects of the extensive cultivation of this plant: its environmental consequences, the relationships between producers, exporters, and consumers; but above all, the power of a simple fruit to reveal something of ourselves.

You have a Ph.D. in art history from NYU and specialize in the history of photography. You have said that knowing the technique helped you to understand artistic processes and go beyond the vision of an ordinary spectator. How did that experience help you to think about the Banana Craze show?

When Blanca Serrano and I were finishing our doctorate, we began to do curatorial work on contemporary art. We applied to Cuchifritos, a space run by an artists’ collective at the Essex Street Market, the last original market in New York. We won the call and made Bitter Bites, an exhibition with the work of three artists, and in it, we talked about the relationship between the global south and the north based on migration and fruits.

Then we realized we could focus on a single fruit and start exploring a big world. We chose the banana because of all the contemporary connotations it has. We made a list of works. We found a lot of them, and then the pandemic arrived. Blanca was in Spain, I was here in Colombia, and we realized that digital humanities could be an ideal medium to materialize our project.

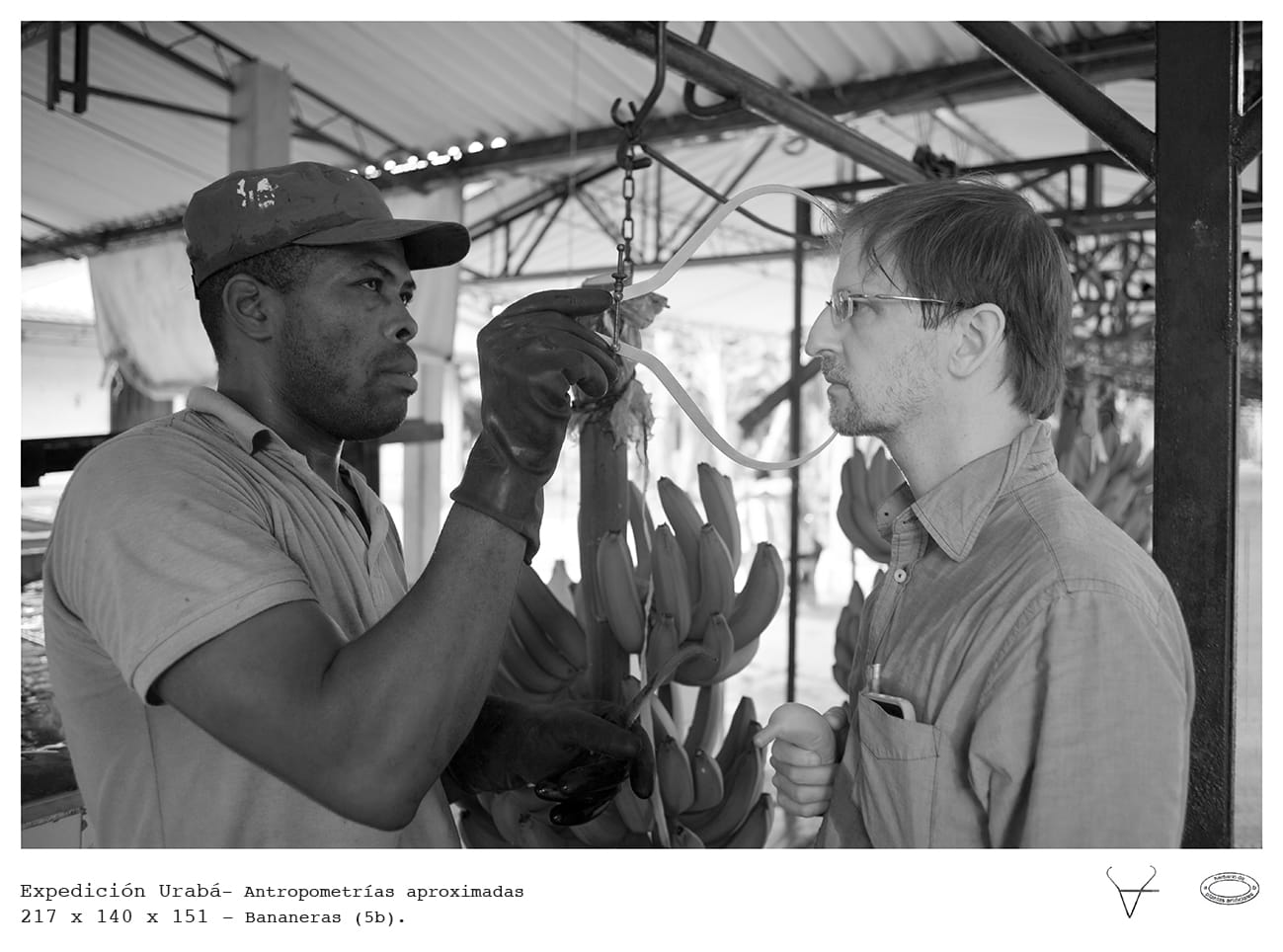

We won a grant from the Universidad de Los Andes and began investigating. La Fiebre del Banano brings together 100 Latin American artworks in which the banana is the protagonist and articulates three cross-cutting themes: violence, environmental impacts, and the construction of identities. The idea of the project is that, by studying these works, we can understand how the massive cultivation of bananas contributed to the increase of social inequalities in Latin America, transformed ways of life, altered landscapes, and contributed to the configuration of xenophobic, racist and sexist stereotypes of its inhabitants. The exhibition provides a panoramic view of the presence of this fruit in contemporary art, considering several decades and numerous countries, as well as the artistic practices of the diaspora.

The exhibition has three axes: identity, ecosystems, and violence. Why did you choose to classify the works according to these themes?

Once we had a long list of works related to the banana, we began to see the common threads of those narratives, and we came up with these three major categories that encompass the pieces on our list, which also allowed us to make crossings between them.

The category of violence is one of the broadest we have. Apparently, the banana is an innocuous and harmless fruit. Still, it has been the motive for many forms of violence exercised by foreign multinationals and corrupt states where banana enclaves have been established. There are differences in each context, but there are also patterns in how the crops were established.

An exciting work to discuss this topic is Jose Alejandro Restrepo’s Musa Paradisiaca, in which he installs many bunches of green bananas on the gallery’s ceiling. At the tip of the banana blossom, he places video monitors on the floor with tiny mirrors that reflect the images that are being projected. The photos he chooses to launch are taken from the press and allude directly to the Colombian armed conflict, especially from the 1980s when the fight against drug trafficking increased. He establishes a relationship between this wave of violence generated by a plant with the first wave of violence of the first half of the twentieth century, appealing directly to the massacre of the banana plantations.

“There is a term used in the United States to refer to Caribbean migrants: ‘plantain.’ It’s one of the ways you see how this fruit, and food in general, has been a tool to signal identities in a xenophobic and racist way.”

In a world increasingly plagued by the climate crisis, talking about ecosystems through art is urgent. What kind of works did you include in that section?

The works there explore the environmental impact of banana monoculture in Latin America and the Caribbean and address issues such as the landscape transformation, the health hazards associated with plantation work, and the symbolic place of bananas in the realm of visual culture. There we have the work of María José Argenzio, 3° 16′ 0″ S, 79° 58′ 0″ W, whose title is a geographical position. She coated a banana plant in El Oro province, southern Ecuador, with the gold plating technique and made two images: one in zenithal, where you see the little golden dot in the middle of a plantation, and in the other, you know the golden plant at ground level.

Maria José plays with Ecuador’s two major extractive products, which have been gold and now bananas, and ironically with the name of the province called El Oro. She brings to the table the magnitude and importance of today’s banana economy, an industry that needs a lot of regulations, especially labor regulations.

Banana exploitation has also shaped our identity as Latin Americans to this day. How did you work on this idea in the exhibition?

We have tried to reflect on national, cultural, labor, racial and sexual identities. The banana has been a national symbol and a figure used to speak pejoratively and racially denigrate people from the so-called “banana republics.” Here we are also talking about xenophobia, racism, and sexism.

There is a term used in the United States to refer to Dominicans and, in general, to Caribbean migrants: ‘plantain.’ That is one of how it is evident how fruit and food, in general, have been a tool to designate identities in a xenophobic and racist way. One of the works that address this is, for example, Bananhattan by Yunior Chiqui Mendoza. Yunior makes a map of Manhattan Island, playing with the appellation ‘The Big Apple,’ but this time, he transforms the figure into that of a banana. He puts the background in yellow and in black as if they were the spots of the banana, the places inhabited by the Dominican communities.

In terms of sexism, the phallic shape of the banana has been very provocative. Women have been sexualized by the gesture of holding a banana and eating it. Many artists have reversed that image and have played with it. One is Victoria Cabezas, a Costa Rican artist who migrated to the United States in the seventies. When she came to study art, Victoria realized that people established a direct relationship between Costa Rica and bananas. She begins an investigation and starts understanding all the pejorative readings around bananas and banana republics. Then, she seeks to reverse these readings through his works. Among the many of her works, one is a soft, plush banana, playing with the idea of the sex toy but also turning something that is hard by nature into a delicate object and that is, in some way, feminized, infantilized. En el Bosque, she takes that giant banana and takes some pictures of a man dressed in a jacket and tie in a forest, touched by that big plush banana.

What was the role of digital humanities in the creation of this project?

They were an incredible tool because they allowed us to write longer texts. It is no longer an exhibition that was over after three months, and the platform also allowed us to play with the diversity of reading layers that artworks have.

Many times what happens in exhibitions is that by fitting them into an axis, one directs the viewer’s reading to some extent. The advantage of the digital format is that people can expand these reading possibilities, and artists can place the same work in two different categories. We also made a chronology, stimulating the reader’s active role in the interpretation and allowing users to create their narratives and readings.

This year we will make the first physical exhibition, which will be small, but we will be delighted. The exhibition space will be the Centre for Visual Arts at the University of Denver. This university serves a substantial Hispanic population, and many students have food security issues. It’s a long-distance curatorship. Nine works are going there, and one not yet on the page is the Coquitos projection by Forensic Architecture and the Comisión de la Verdad (Truth Commission).

The project continues to grow little by little. We continue to find works and expand the reflections this fruit allows us. Our goal is to preserve the memory of the banana in Latin America and to build a discourse around contemporary artistic practices committed to this reality.