The last time that the Mexican photographer Yael Martínez went to the Montaña de Guerrero was a party in the town, for a patron saint. All was a celebration and joy. He had contact with the originary communities in the zone because he has made connections from before with the help of colleagues, organizations and time. Tranquility reigned. He took some photos, worked for a couple of days, and left. A day later, the tragedy: armed people arrived in the area and, without a clear motive, they murdered three people. “Although there is always an apparent calm, it can be break at any time,” says Yael.

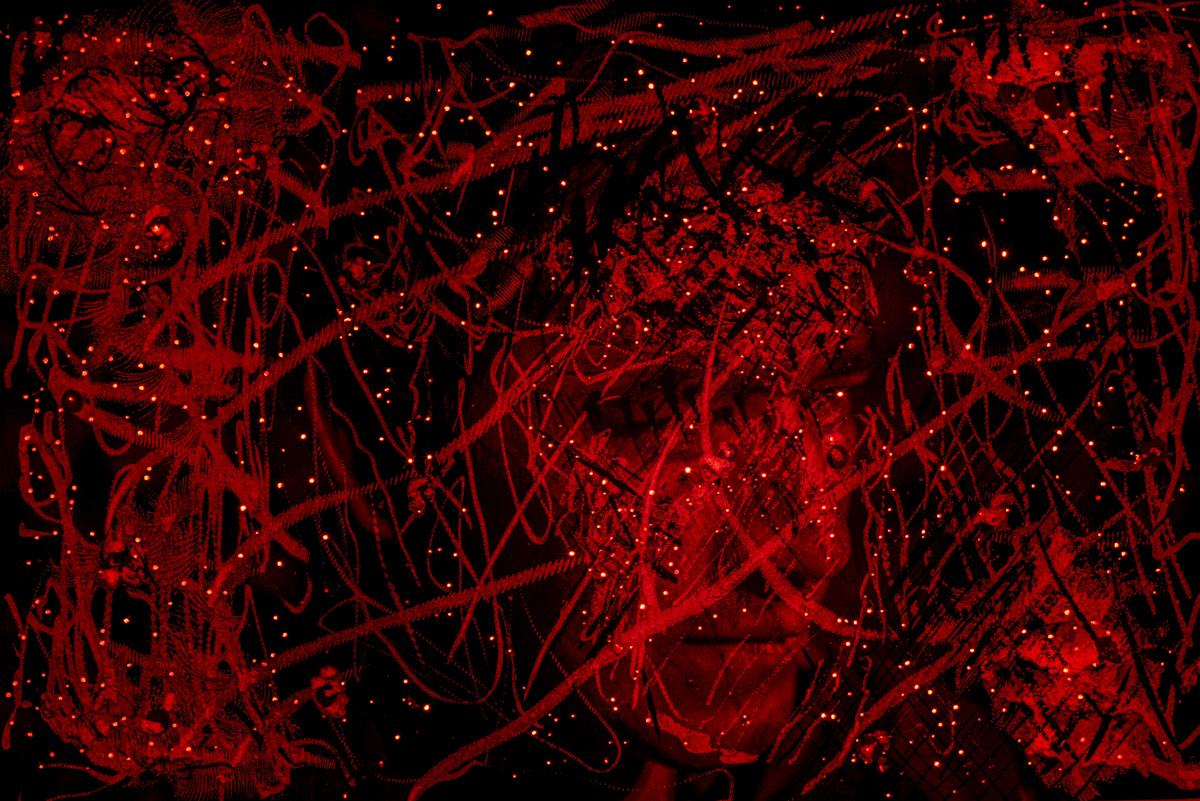

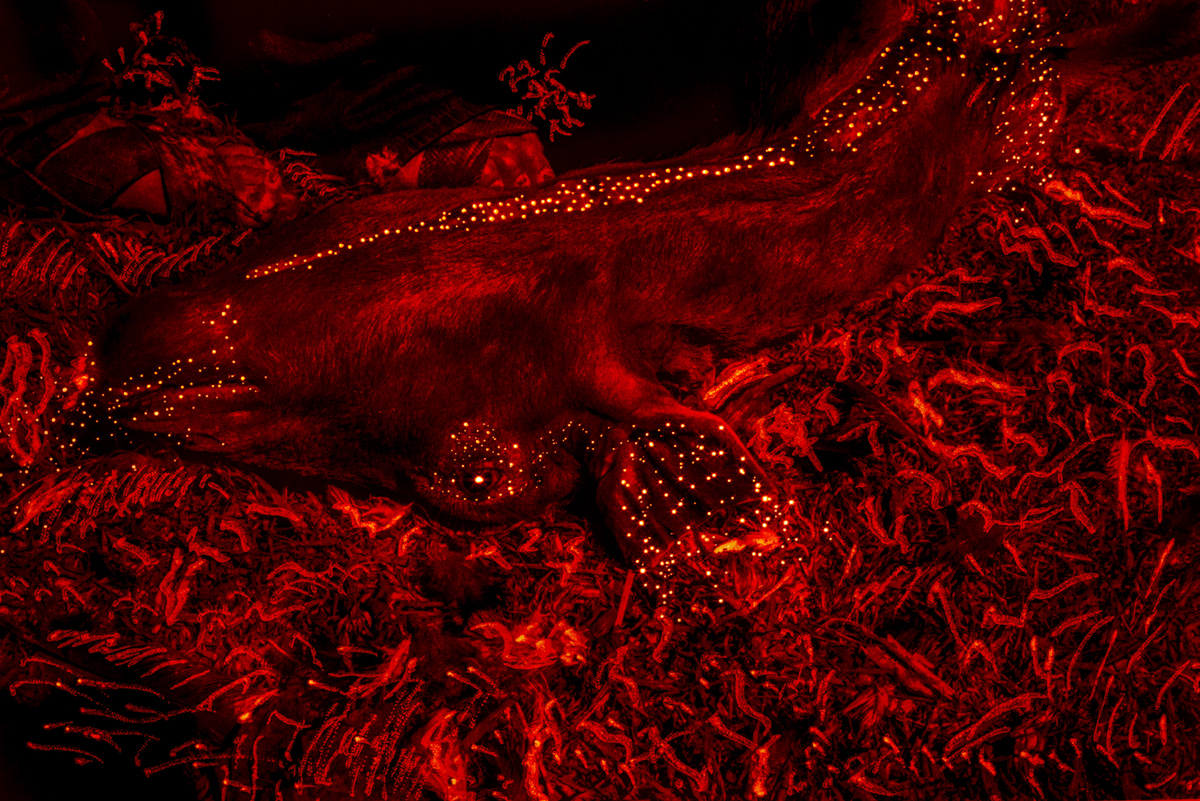

The Guerrero state is since the 70s, one of the major opium producers in the world, after Afghanistan and Myanmar. How to tell that fine equilibrium between the original rituals of a community that tries to survive and the framework of one of the markets that move the most money in the world? How to portray the sweetness of poppy petals and, at same time, the number of pores that violence can enter ? Yael chose, to do it, the red colour: red poppy, red blood. “It’s like this flower is popping somehow, creating a pop,” he says.

For years, the Mexican artist has been thinking about how to tell stories that go through the drug trade. In 2013, Yael faced the disappearance of three family members and began to look for new ways to portray violence in everyday life. He contacted others who were going through the same thing and from there Luciérnagas was born, a work in which he intervened photographs with needles of different sizes to put light where there only seemed to be darkness.

His current work is part of that great stage that he inaugurated then. The poppy is the backdrop against which he prints stories about life, death and the spirituality with which to go through them. Son of a family of jewelry artisans in Taxco, Yael became a prestigious local and international photographer. Since 2020 he is a Magnum Nominee and a member of the Magnum Foundation, as well as being part of the Eugene Smith Foundation, where he won the 2019 award.

What is the new stage of your work about?

This is a second chapter of the Luciérnagas (fireflies) project, which came from the idea of working with native communities that had always been invisible. I proposed the project to be carried out within the Luciérnagasproject, but taking into account these communities that are dedicated to scratching the poppy in the mountains of Guerrero. The idea is, precisely, to speak of a mountain from a more symbolic aspect and to try to break the stigmas that are created around the communities that are dedicated to the growth of poppies in the state of Guerrero.

Is the treatment of images different from Fireflies?

We wanted to take up this idea of the flower as a symbolic element. So the flower with this red color represents, in some way, blood, violence but also life, passion. In a way, this idea of the interventions is as if they were macro images of the flower. It’s like this flower is bursting in some way, generating a pop. This outburst penetrates the whole question of the life of the indigenous communities. Although the native communities in Guerrero do not use the flower in an ancestral way, as happens with the coca leaf in other latitudes, we represent the fact that the cultivation of the poppy flower has come to change the social and political structure of the community, since the 70s. The idea is to talk about all the cultural richness of the original communities and try to break stereotypes. I want to show this worldview of them and the work they do to earn a living but talking about reality and the way of understanding practices.

How have you built the link with the communities?

Due to the same stigmatization, entering there many times is no longer so easy. They have become more airtight. In 2017 he had done a first work, which was also collaborative, on indigenous communities in the low mountain region. It is a project that I did with my brother. These are intervened photos that we took in 2016, 2017. In some way, I already had links with the high mountain region and the surroundings, also going down to the Costa Chica. To carry out this work, I am very grateful for the support of the Center for Human Rights in the mountain, Tlachinollan, and my friend and colleague Lenin Mosso. It was through them, who have lived and worked in the mountains for decades, that I have been able to access these communities.

How does the territory feel from the inside?

The last time I went we were working in a community and there was a feast for a patron saint. Everything was calm, easy, we worked for a couple of days. We went out and the next day we left they murdered two or three people. So the difficulty is suddenly that: although there is always an apparent calm, that apparent calm can be broken at any moment. The motive for the attack was unknown. There was the party and, suddenly, the armed people arrived.

What do you mean by this project?

It is closely linked to what I investigated in Luciérnagas. The idea is to talk about communities that have been resilient for a long time, that are permanently surrounded by these processes of violence and that, in some way, have managed to keep cultural coherence alive. So, in a way, for me this was one of the chapters that is important to talk about and link it with the work with the families of the disappeared. There is a close link that surrounds the project around violence and drug trafficking but, particularly, how this has changed the cultural and social dynamics of these communities.

The idea is to remove the stigma. Many people think that there is an economy here that is based on drugs, that there are people who become rich overnight. But many of these communities have been paying around thirteen to seventeen thousand Mexican pesos for generating a kilogram. Those who grow poppies can do it twice a year. We are talking that for two kilos of rubber it is around 26 thousand pesos which have been like one thousand three hundred dollars a year. In a way, it is the initial link in this chain. They are just surviving.

This work was done with support from the New Narratives on Drugs Investigative Journalism Fund, which arises from the alliance between the Gabo Foundation and the Open Society Foundations (OSF).