Who are “The Undisciplined” in Peruvian Photographic Art?

Edited by Alejandro León Cannock, the book “El Arte Fotográfico en el Perú. Balance y Perspectivas (1990-2018)” gathers reflections from scholars, curators, and artists about the changes that Peruvian photography has undergone since the emergence of a generation of artists, including Roberto Huarcaya, Luz María Bedoya, Flavia Gandolfo, Juan Enrique Bedoya, and Milagros de la Torre. In this conversation, Cannock discusses the impact of this generation on contemporary Peruvian photography and responds to recent criticisms against the work of Huarcaya, selected to represent Peru at the 2024 Venice Art Biennale.

By Alonso Almenara

For those living outside of Peru, it must be difficult to understand why every participation by the country in international art events like ARCOmadrid or the Venice Biennale always ends up mired in bitter controversies. Is it a sign of a society where contemporary art has a massive reach and elicits critical reflections from diverse sectors? Not at all. In reality, the Andean country’s theory, critique, and art historiography have had limited development and are characterized by gaps and mysteries.

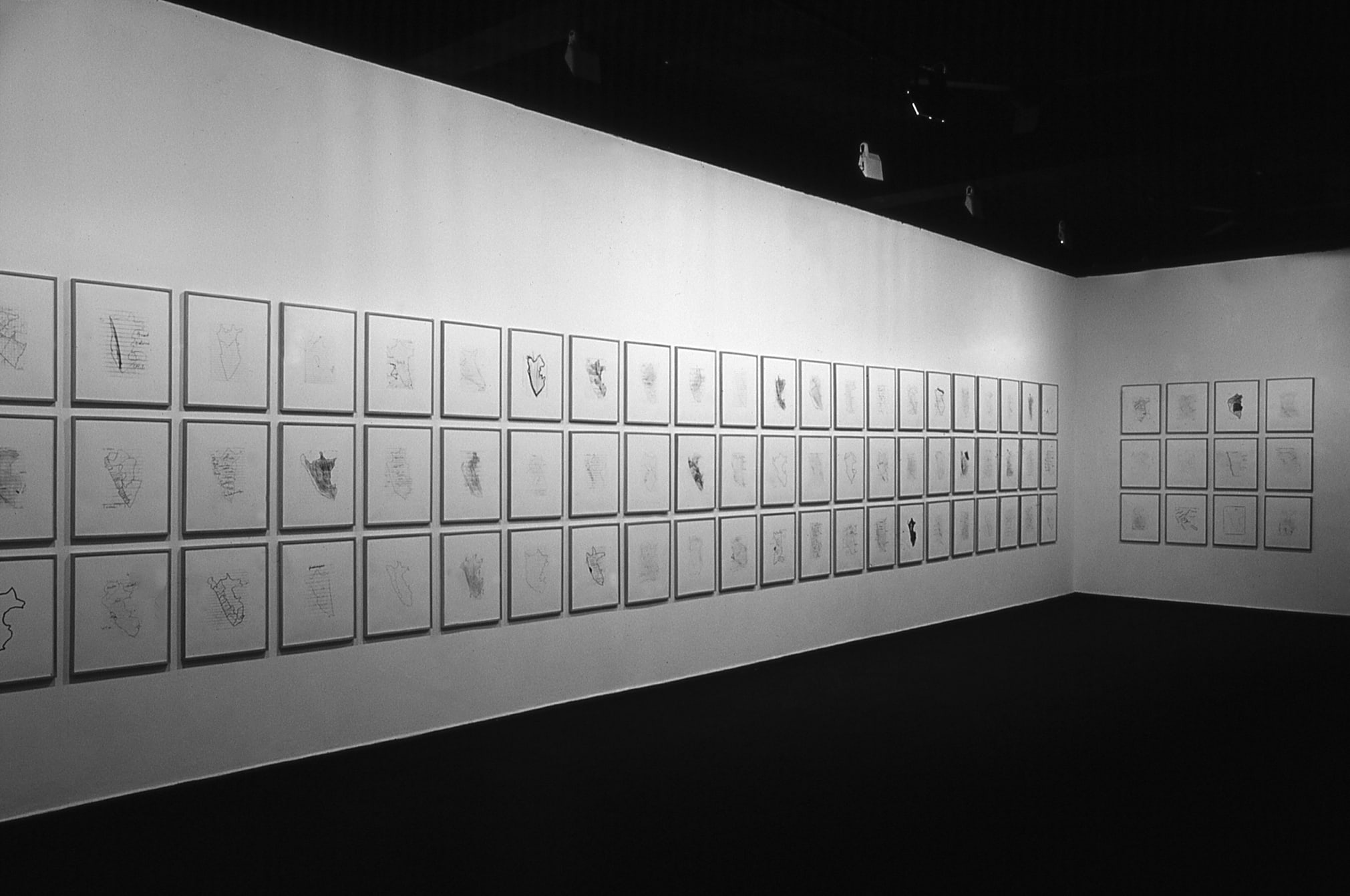

The symposium “El Arte Fotográfico en el Perú. Balance y Perspectivas (1990-2018)” is one of the recent efforts to change this situation. It took place on Friday, October 5, 2018, as part of the international conference “Las razones de la estética. Debates contemporáneos sobre los sentidos de la aisthesis,” organized by the Research Group in Art and Aesthetics at the Pontifical Catholic University of Peru. The presentations from that event have been compiled five years later, with pandemic-related complications, into a book published by KWY Publishing.

Philosopher and Peruvian photographer Alejandro León Cannock, the volume editor, writes on the back cover: “The main objective of the symposium was to contribute to the construction of a critical space around artistic photography in contemporary Peru.” He adds a series of questions reflecting the publication’s nature: “Can we speak of ‘contemporary Peruvian artistic photography’? What would define its nature and logic? What events condition its existence? Who are the actors that participated in its constitution? What elements were adapted from the international scene? What continuities and ruptures occurred concerning the history of photography in Peru?”

“The book has a very particular nature,” Cannock explains, “as it consists of transcriptions of presentations. This means that the form of the texts is related to orality and more to intuitions, quests, rather than the conclusions of finished research processes.” Among the invited authors are curators like Jorge Villacorta, Carlo Trivelli, and Giuliana Vidarte; academics like Mijail Mitrovic and Carlos Zevallos Trigoso; and photographers like Luz María Bedoya. A second set of texts was commissioned from authors who did not participate in the symposium, and Cannock asked them to react to the presentations. “Reacting can mean criticizing in opposition, it can mean criticizing as discernment, it can mean complementing, taking an idea and extending it, or even forgetting the text. I wanted the commentators to feel completely free to contribute something new based on their reading experience to add complexity and more perspectives to the field I was interested in sketching.”

“El Arte Fotográfico en el Perú. Balance y Perspectivas (1990-2018)” is a publication that stands out not only because it seeks to fill a void but also because it is the first installment of a new series of publications dedicated to theoretical reflection on photography by the KWY Publishing, titled ‘El Pensamiento de la Imagen’ (The Thought of the Image). At the heart of the book is the desire to assess the contributions of a generation of photographers Cannock has called “The Undisciplined”: Roberto Huarcaya, Luz María Bedoya, Flavia Gandolfo, Juan Enrique Bedoya, and Milagros de la Torre. They emerged in the late 1980s and early 1990s in the still undefined space between photography and contemporary art, introducing conceptual practices and new ways of thinking about the relevant image. They have generated their local tradition, with many of these figures later becoming involved in education through the Centro de la Imagen, Lima’s most influential photography school.

Returning to the topic of controversies, Roberto Huarcaya, who served as director of the Centro de la Imagen for several years, has made headlines recently because his project “Cosmic Traces,” curated by Cannock, was selected to represent Peru at the 2024 Venice Art Biennale. The discussion sparked by this decision is significant in that it makes explicit the underlying antagonism between what is perceived in Peru as official, Lima-centric, and white art and what exists beyond art from the regions, indigenous peoples, and those whose first language is not Spanish. Kindly, Alejandro agreed to discuss all these topics with us.

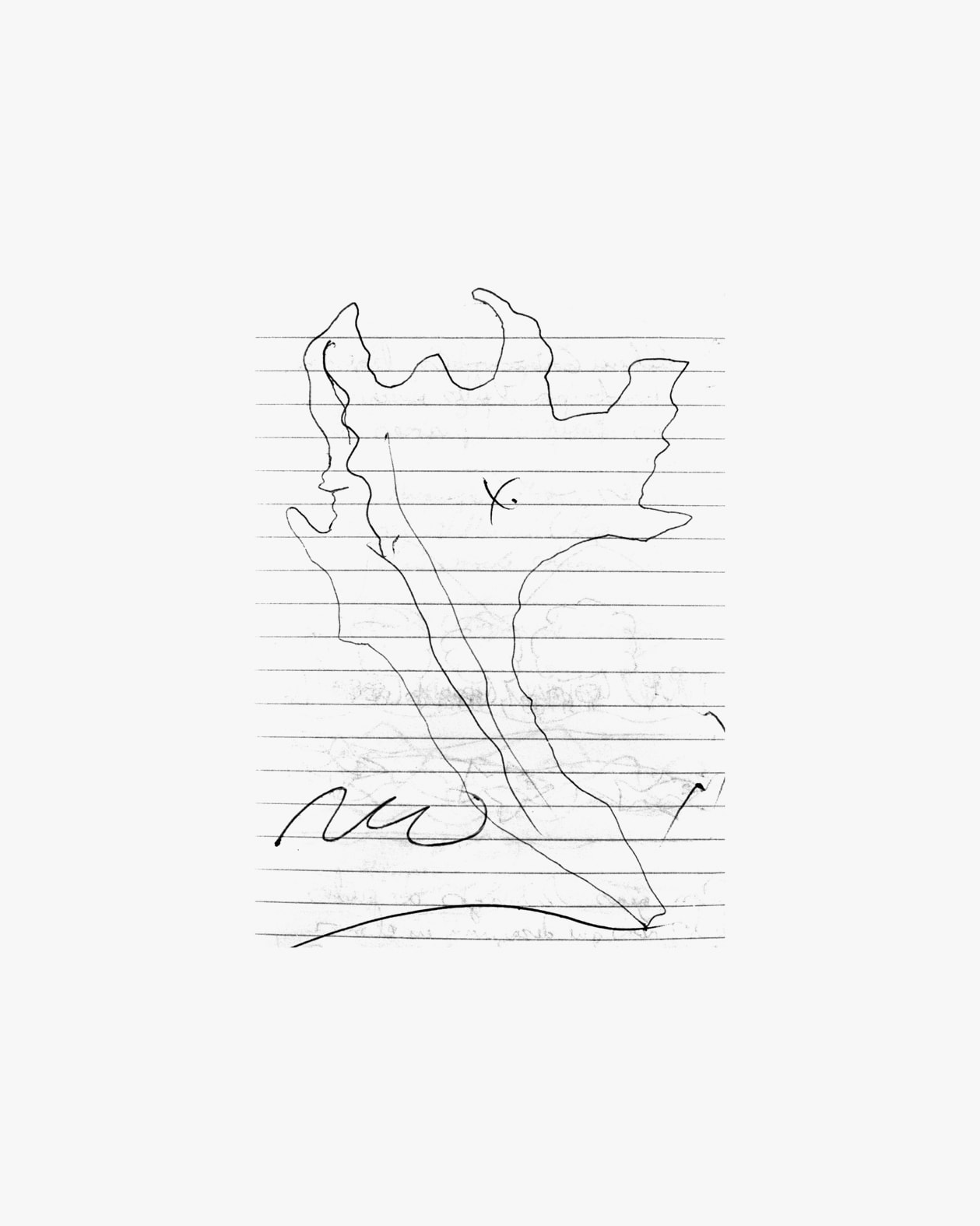

Milagros de la Torre. Series Bajo el sol negro.

It’s always good news when academic publications with theoretical reflections on the photographic tradition in Peru appear. In part, this is because it happens very rarely. Why do you think this is?

I entered the world of photography relatively late. I studied philosophy, worked as an ethics professor at UPC and the Catholic University, and only delved into photography when I was in my thirties. I entered through photographic practice and immediately became interested in reflection. One thing that caught my attention is that there is very little criticism, history, and theory regarding photography in Peru. There are valuable works like those of Andrés Garay, who I believe is the researcher in Peru who has taken the study of archives and photographers from the first half of the 20th century most seriously, in places like Arequipa and Cusco, such as the Vargas brothers, Martín Chambi, and so on. Next to him, you have the curatorial work of Jorge Villacorta and the work of Carlo Trivelli from a more journalistic and curatorial perspective. There have been very few photography magazines or magazines about photography, and they have mainly focused on popularization. Fortunately, we now have “FOT. Revista de fotografía e investigación visual” from UPC, which significantly contributes to the field of photography in Peru and Latin America. However, academic theoretical reflection works are generally quite scarce. So, one of my longstanding wishes was to push things forward so that people start thinking more about the medium and its implications.

That’s how this project came about in 2018, in the context of an international aesthetics conference organized by the Research Group in Art and Aesthetics at the Catholic University. I proposed a roundtable that addressed this topic, and it was accepted. I intended to gather as diverse a group of guests as possible: I was interested in the perspectives of academics like Mijail Mitrovic or Carlos Zevallos Trigoso, as well as curators like Villacorta or Trivelli. I also wanted to include artists. In other words, I’m interested in reflection on the medium not only from outside of theory but also from the practical experiences of the creators themselves.

Initially, only Luz María Bedoya, who has a background in reflection and writing, accepted the invitation among the artists I invited. Now, the book is structured into two parts: the first includes the presentations at the conference, and the second consists of texts from other authors who comment on these presentations. Among these commentators, there’s one more artist, Maricel Delgado, who wrote a text I love. It’s short but breaks away from the expectations of what one imagines an academic text to be. So, let’s say I was interested in bringing together the voices of people involved in the world of photography with all its blurred boundaries, but people who could shed light on the period we wanted to encompass in the discussion.

You refer to the period that began in the late 1980s and early 1990s. What makes that period significant for Peruvian photography?

Returning to Andrés Garay, he has worked extensively to recover photography from the late 19th century and the first half of the 20th century, known as the era of Surandino photography, concentrated in Arequipa and Cusco. Then, there is more information about certain local modernism of the 1970s, specifically the group from the Secuencia photo gallery, including Billy Hare and Fernando La Rosa. These photographers attempted to institutionalize photographic practice as art. In other words, they sought to give the medium self-awareness from an artistic perspective, which involved various elements not specifically related to photography but linked to the construction of a field: establishing a gallery, publishing a small magazine, translating canonical texts from international modernism into Spanish for publication in that magazine.

This is what began to define artistic practice in the field of photography. What happened in the late 1980s and early 1990s is that a new generation emerged that wasn’t connected to either of those two traditions: not to the testimonial tradition documented by Augusto del Valle in a book published a couple of years ago about the Interfoto movement, formed by photojournalists who documented all the upheavals in Peru in the late 1970s and early 1980s, nor to the Secuencia movement, which represents a more formalist, artistic use of photography. I’ve called this generation “The Undisciplined,” using a somewhat provocative name. These photographers don’t come from a traditional photography background or an art school. They come from other disciplines: Roberto Huarcaya from psychology, Luz María Bedoya from literature and linguistics, Flavia Gandolfo from history, and Juan Enrique Bedoya has a legal background. The only one with more photographic knowledge is Milagros de la Torre, who studied at the Faculty of Communication at the University of Lima before going to England.

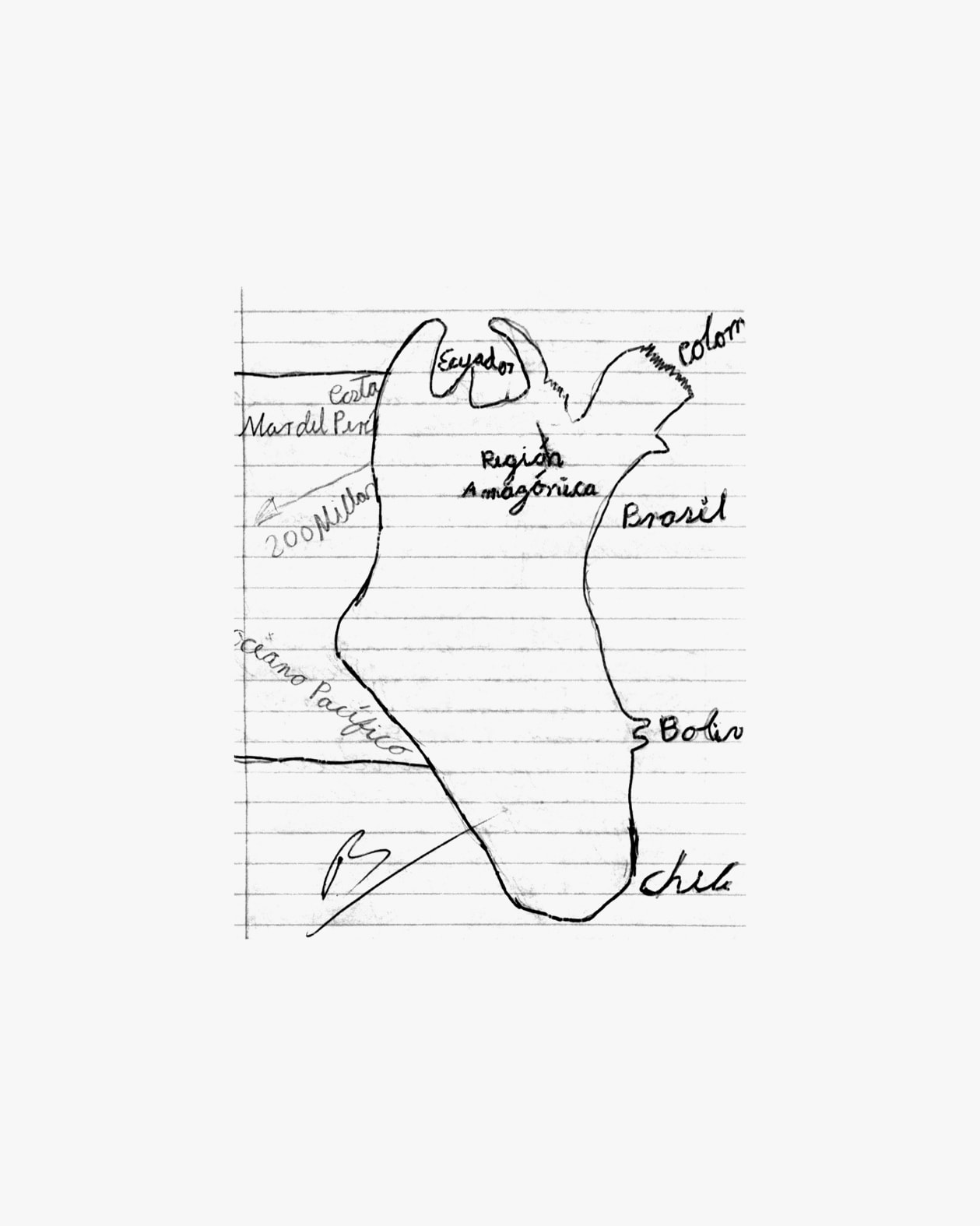

Luz María Bedoya. KM 948 N. Series Punto ciego.

In the first three decades of the second half of the 20th century, certain photographic practices began to develop in Lima. Initially, these practices were related to photography as a record of reality, stemming from photojournalism—documenting social movements, marches, and so on—or associated with documenting specific social groups, such as event photography and artist portraits. This could be categorized as documentary photography, which saw significant development in our country with the Taller de fotografía social (TAFOS), created in the late 1980s by Thomas Müller and his wife, Helga Müller. By the way, this workshop is a pioneering case of participatory photography studied worldwide.

In parallel to this tradition, the Secuencia photo gallery movement began to develop in the 1970s, bringing inspiration or adaptation from late American modernism, with figures like Aaron Siskind, Minor White, and others, represented by Billy Hare and Fernando La Rosa. They attempted to institutionalize photographic practice as art. In other words, they tried to instill self-awareness in the medium from an artistic perspective, which involved a series of elements not strictly related to photography but connected to building a field: creating a gallery, publishing a small magazine, translating canonical texts from international modernism into Spanish for publication in that magazine.

That is what began to define artistic practice in the field of photography. What happened in the late 1980s and early 1990s is that a new generation emerged that wasn’t linked to either of these two traditions, nor to the testimonial tradition documented by Augusto del Valle in a book that came out a couple of years ago about the Interfoto movement, formed by photojournalists who documented all the upheavals in Peru in the late 1970s and early 1980s, nor to the Secuencia movement that represented the artistic and more formalistic use of photography. I’ve called this generation “The Undisciplined,” using a somewhat provocative name. These photographers don’t originally come from a traditional photography background, but they also don’t come from an art school. They come from other disciplines: Roberto Huarcaya comes from psychology, Luz María Bedoya comes from literature and linguistics; Flavia Gandolfo from history; Juan Enrique Bedoya has a legal background. The only one with a more photographic background is Milagros de la Torre, who studied at the Faculty of Communications at the University of Lima before going to England.

They are doubly undisciplined in my view because, on the one hand, since they don’t come from a formal photography school, they are not obliged to adhere to the medium’s canons, such as well-exposed photographs, proper lab printing, and matting for framing, etc. On the other hand, they tend to see the photographic medium as an instrument for representing reality and as a space for thought. That is how they began to produce photographic projects that, in line with what has been happening in the international photography scene for some time, break the boundaries of the medium to encompass hybrid, post-media practices that were not common within the academic canon of documentary and modernist artistic photography.

Could we say that a new post-photographic paradigm emerges? And on the other hand, does this have any relationship with the political situation in the country? We are talking about a period in which, on the one hand, neoliberalism is established with Alberto Fujimori, and, on the other hand, an armed conflict persists between the Peruvian state and the Shining Path. In other words, what this new generation brings to the scene is a mere aggiornamento, an update concerning what is happening in the North, or does it have a political dimension as a response to the local crisis?

On one hand, I believe there is a sort of retreat. There is a book called “Franquicias Imaginarias” written by Jorge Villacorta and Max Hernández Calvo, which addresses the transformation of the visual arts field in Peru in the 1990s. The book suggests that in the 1990s, the visual arts retreated into subjectivity, a gesture of seeking refuge in intimate, personal, domestic stories. One of the authors’ hypotheses is that this retreat is related to the context of political violence, the destruction of public space, democracy, and fear, of course. Perhaps this generation of photographers may have moved in that direction without being aware of it.

On the other hand, many of them went abroad at a young age for studies: Luz María Bedoya, Flavia Gandolfo, and Juan Enrique Bedoya spent time in the United States, Milagros de la Torre studied in England, and Roberto Huarcaya traveled to Cuba and then to France. So, there is also a factor related to the absorption of trends in contemporary photography that, in that context, I wouldn’t call post-photographic yet. Still, it’s a sort of late postmodernism, if you can call it that. A movement linked to the Pictures Generation in the United States, including artists like Richard Prince and Cindy Sherman. I think the spirit related to appropriation, collage, the absence of technique, and the idea of creating hybrid objects and using photography not so much as a representation of reality but as a space for ideological critique impacted these artists. I don’t know if it was explicit or conscious because the dimension of ideological critique is less noticeable in Peru, but using the image as a space for conceptualization did have an impact.

Flavia Gandolfo may be an exemplary case of this new way of understanding the medium, where iconological analysis and ideological critique go hand in hand. Her project “Historia,” for example, includes photographs of maps of Peru drawn by children from public schools. She reflects on the impossibility of representing ourselves as a nation with these pieces. In any case, what was happening in the international scene in Northern Europe and the United States since the late 1970s began to happen here in the early 1990s.

Is this a connection solely with the North, or is it a phenomenon that also reflects what is happening in other Latin American countries?

Here is something interesting: these are two different movements that intersect. There has been a movement in the field of contemporary art starting from the 1960s, both from the North and Latin America. I think, for example, of Luis Camnitzer (Uruguay), Pedro Terán (Venezuela), and Eugenio Dittborn (Chile), among others. It’s a movement in which photography is gradually incorporated as a medium among others to artistically consider the world. There’s a rhetoric of the post-media: it could be painting, video, photography, it doesn’t matter. This process of artifying the photographic image from contemporary art occurs in Peru with the work of artists like Juan Javier Salazar, Herbert Rodríguez, or Jaime Higa, who in the 1980s used photographic images from newspapers to create pastiches and social critiques. They, so to speak, introduced an artistic dimension to photographic images that have nothing to do with the fine art image from the modern photographic museum.

In parallel, there’s another movement from the field of photography where the photographic image began to be conceived as an artistic image. That happened with Billy Hare and Fernando La Rosa: they reaffirmed the artistry of photography through the medium’s qualities, using the language of modernism theorists like Greenberg or Szarkowski. The generation I’m talking about—Huarcaya, Gandolfo, etc.—is in dialogue with what was happening in art. Still, it’s a movement primarily from photography, an internal movement of artification of the photographic image.

So, to answer your question, I think there were parallel movements in Latin America in the 1990s. Alejandro Castellote, a Spanish curator, published a very important book in the early 2000s called “Mapas Abiertos,” where he reviews the trends in Latin American photography of the 1990s about art. He mentions works such as that of the Argentine Marcos López, who used staging and fictionalization as a postmodern gesture of artistic creation in photography to reconsider the identity of the Argentine people. Or the work of the Guatemalan Luis González Palma, who uses new materials but also revives old processes. Or the work of the Brazilian Rosângela Rennó, who, through the questioning of various types of images (archives, press, etc.), invites us to think about various forms of oppression, mainly the oppression that women face under the patriarchal order. These authors are linked to what is known as an expansion of the field of photography. So yes, I would say it is also related to the Latin American movement.

I would like to talk about some of the texts included in the book now. What kind of contributions do we find here?

As I mentioned, I like Maricel Delgado‘s text: she comments on the presentation by the researcher Christian Bernuy on alternative photographic practices of the 1990s, such as the use of the pinhole camera. But Maricel’s text doesn’t delve into this topic; instead, she reacts from the creator’s point of view and creates a brief narrative about the place of doubt, stumbling, and the precariousness of the thought process in artistic work. It’s a text halfway between advice for young artists and a personal confession of her own experience as a mother, a teacher, and an “intermittent artist,” as she defines herself. I like it because it breaks away from academic expectations but invites us to think from a first-person experience about the experience of a photographer who belongs to the generation focused on in the book.

Then, I find other texts interesting for their contribution to the historiography of photography in Peru. One of them is the text by Giuliana Vidarte, which discusses representation practices in the Amazon, drawing a connection between photography and painting. The commentary on this text is provided by Morgana Herrera, a researcher who also works on topics related to the Amazon, and she expands, adds other perspectives, and additional references to the discourse proposed by Giuliana. I think this is interesting precisely because the historiography of Peruvian photography, despite the work of Garay and Villacorta, which examine what happens in other regions like Cusco and Arequipa, is very focused on Lima. There is an increasing movement of young photographers, collectives, magazines, and schools in the north, in Trujillo, Cajamarca, and Cusco. For me, these research efforts exploring the medium’s use in other regions are essential.

“The history from which photography is defined can be rewritten. I like to define it from the idea of the fabric: the photographic apparatus as an instrument that connects us with others. I don’t use the camera to steal from others. I use the camera as a bridge that allows me to weave a connection with others. But also to weave a connection between the past and the present, between here and there, between the familiar and the foreign.”

Now, I’m interested in your opinion on what happened after the generation of Luz María Bedoya, Milagros de la Torre, etc. Have there been other significant phenomena in the development of Peruvian photography since then?

After the 1990s, the neo-liberalization of the economy, the advent of media like MTV, computers, later cell phones, the internet, and the digital revolution led to a leveling. I won’t say homogenization but rather a flow of trends, practices, and styles between Peru, the region, and the world. So, today, it’s very difficult to find major differences or chronological gaps as there used to be. The big novelty is the digitization of photography and the possibilities this could have opened up for what you previously referred to as the post-photographic. I believe this is a trend that hasn’t been explored much in Peruvian photography: I’m referring to the use of appropriated images from the internet, digital platforms as a means of dissemination, etc. It’s worth mentioning that during the pandemic, a duo of photographers, Alejandra Orosco and Paul Gambin, created a project that I find very interesting because of its relational, interactive, and virtual character, but especially because it directly responded to the global crisis we were experiencing at that time: “A Pandemic Love Story.”

However, beyond the introduction of the digital variable, I don’t think there has been such a strong paradigm shift as there might have been in the early ’90s for a precise reason. There is no longer a canon of photography to break or transgress. When that canon is shattered, a legacy of contemporary art and postmodernity, everything becomes possible in the expanded field of photography. So, some practices cross the entire spectrum without anyone being able to bring something radically new as the new uses of the medium that the generation of Huarcaya, Gandolfo, etc., brought to our scene. However, we will have to see where artificial intelligence development may take us in the coming years (or months). Perhaps there, a new paradigm shift in global photography and art could be generated.

I believe that interesting things have been happening in recent years related to the use of documentary photography from a perspective that some call authorial, others call poetic, and others call subjective. It’s a trend that is not only Peruvian but also regional, using photography to tell stories, intending to address reality social issues, but introducing a sort of aesthetic filter, almost like a return to the pictorialism of the 19th century. I like the work of Yael Martínez, which deals with the harsh realities of Mexican society related to drug trafficking, which he has experienced himself. At the same time, he soars his projects into dreamlike, poetic realms that can be sublime or heartbreaking. Projects are moving in this direction in Peru, such as Prin Rodríguez or Fernando Criollo.

What you’re saying makes me think of Florence Goupil, whose documentary also incorporates magical or dreamlike elements. Would you consider her as part of this last group? I’m referring to her photos that document the way of life of the indigenous peoples of the Amazon and their relationship with master plants.

Your example is interesting because I believe there is a difference right there. I’m familiar with Florence’s work; I like it very much, but I wouldn’t categorize it as artistic. Here, we can enter into the eternal discussion of the limits or criteria for defining photographic work as artistic (or not). Indeed, in her projects about medicinal plants and the communities that use them, there is a desire to tell stories, an approach to details, objects, and portraits that invite us to enter the universes she’s portraying. There’s interesting formal work but not a genuinely plastic engagement with the image.

In French, they use a term that isn’t widely used in other countries: they speak of Photographie Plasticienne, plastic photography. It’s that point at which the photographer begins to work with the materiality of the image. It’s not just about the form of representation, which is what the modernists talked about—the framing, the quality of the print, the zone system, etc.—but about looking at the image not primarily as an iconic representation of the world but as a plastic material to work with. Going back to the example of Yael Martínez or Prin Rodríguez, I think there’s a reflection on materiality there. Prin uses old negatives covered in mold or dust, and all that materiality transforms the iconic meaning of the image.

Finally, I’m interested in your opinion on the small controversy sparked by “Cosmic Traces,” the project selected to represent Peru in the upcoming Venice Biennale. This decision is made by a private entity, the Patronato Cultural del Perú, through a competition. You are the curator of the winning project, which focuses on the work of Roberto Huarcaya. The controversy is related to the project that came in second place, centered around the work of the Shipibo-Konibo artist Olinda Silvano, which is perceived as being more aligned with the theme of the 2024 Biennale, focused on the notion of the “foreigner” as an embodiment of otherness or difference. Adriano Pedrosa’s statement gives examples of artists from indigenous communities, although it also mentions queer artists and other types of otherness. Many are asking: why send a Lima-based artist like Huarcaya to Venice?

We knew there would be controversy because there always has been in all of Peru’s participation in the Venice Biennale since the Peruvian pavilion was created in 2015. For me, disagreements are welcome because they generate discussion and advance public debate. However, it seems to me that the angle of discussion, on this occasion, is not well placed because the project has not been revealed yet. Therefore, it can’t be critiqued aesthetically, conceptually, or politically because the proposal’s details are unknown. And that’s because the rules of the competition—accepted by all of us before entering the competition—require confidentiality about the content of the proposals. Starting from there, I believe there’s a sort of disconnect in the controversy.

Thus, the criticism should not be directed at the project or the people behind it. I think it’s more related to arguments from a perspective associated with institutional critique that has existed for much longer and that this competition has, temporarily, reactivated. In this general sense, I believe these questions can be relevant because institutions need to be constantly critiqued and questioned to expose their blind spots, biases, and potential authoritarian and dogmatic behaviors. However, I don’t think we have much to say in this context since we can’t be both the judge and the defendant simultaneously. We decided to participate knowing the game’s rules, and all participants accepted the jury’s decision. This doesn’t mean that we turn a blind eye to aspects that necessarily need improvement.

Anthropologist Luis Elvira Belaúnde wrote an article critiquing the decision of the Patronato, in which she rightly discusses the centralism of these kinds of competitions. She also mentions that the composition of the jury should be reconsidered to avoid, for example, a majority of male members. I agree with that. But it doesn’t entirely depend on the Patronato, an entity made up of institutions that send their representatives. Each institution needs to rethink how they appoint these people. In other words, it’s a structural problem.

I don’t think this critique implies a direct questioning of our project. If Ximena Garrido-Lecca’s project, Kukuli Velarde’s project, or Ishmael Randall-Weeks’ project had won, the questions would have been the same, as the selection process, its actors, and institutions would have been the same. If structural criticism of an institution is legitimate, it should always be legitimate and not just when the result doesn’t seem suitable. We can’t question the game’s rules at the end of the match when the final result hasn’t been in our favor. In any case, the continuous questioning of centralism and sexism in Peru must be sustained beyond this current situation.

La antropóloga Luis Elvira Belaúnde escribió un artículo que critica la decisión del Patronato en el que discute, con razón, el centralismo de este tipo de certámenes. Menciona también que hay que repensar la conformación del jurado para evitar, por ejemplo, que la mayoría de los miembros sean hombres. Estoy de acuerdo. Pero esto no depende enteramente del Patronato, que es una entidad conformada por instituciones que mandan a sus propios representantes. Cada institución tiene que repensar cómo designa a estas personas. Dicho de otro modo, es un problema estructural.

Ahora, no creo que esa crítica implique un cuestionamiento directo a nuestro proyecto. Si ganaba el proyecto de Ximena Garrido-Lecca, el de Kukuli Velarde o el de Ishmael Randall-Weeks, los cuestionamientos tendrían que haber sido los mismos, pues el proceso de elección, sus actores y sus instituciones hubieran sido los mismos. Si la crítica estructural a una institución es legítima, lo debe ser en todo momento y no solo cuando el resultado no nos parece el adecuado. No podemos cuestionar las reglas del juego al final del partido cuando el resultado final no nos ha sido favorable. En todo caso, más allá de esta coyuntura, el cuestionamiento continuo al centralismo y al machismo en el Perú debe sostenerse.

Agreed, but Luisa Elvira Belaúnde’s text suggests that this controversy ultimately revolves around an antagonism between two ways of creating images: on one hand, extractive photography, and the other hand, creative practices she considers more genuine, related to indigenous populations in the Amazon. From her point of view, Huarcaya represents the extractivist trend. This Lima-based white man goes to the jungle to extract images and knowledge from which he benefits without giving anything in return. What do you think about this?

Belaúnde presupposes that what we presented as the project is Roberto Huarcaya’s ” Amazogramas.” That is just one part of the work he has been doing for several years with large-format photograms. “Amazogramas” was created in the jungle, but he has done a similar job on the Pacific coast, in the Andes, in Lima, portraying various characters and aspects of the territory. The large-format photogram constitutes the technique, the artistic medium, that Huarcaya uses to express himself. Let’s not forget that artists are workers, like anyone else, and to develop their work, they use various tools. The second aspect I want to emphasize—and this goes far beyond this current situation—leads us to a beautiful debate that is related to the role of the photographic apparatus in modernity and, indeed, in the colonial and extractive practices that the Global North has developed since at least the 19th century. The photographic apparatus has played in various scientific movements to analyze the other, classify the primitive, and explore territories to exploit rubber gold in the jungle here and there.

In terms of uses, the photographic apparatus has been an ally of extractivist thinking in general. In techno-scientific terms, if we follow theorists like Ariella Azoulay and Vilém Flusser, the photographic apparatus can have programming, software, a disposition even structurally linked to a monological perspectivist vision that distinguishes a subject from an object that fixes, flattens, extracts the vitality, movement, complexity of the issue to precisely, as I say, understand it, control it, and exploit it. The photographic apparatus has thus been at the service of scientific positivism, geopolitical colonialism, and economic capitalism in the context of the emergence of a biopolitical society, as Michel Foucault qualified it. That is undeniable. But it seems that this does not mean that the photographic apparatus is inevitably condemned to obey the dictates and interests of such extractive practices. I agree with what Flusser said about the possibility of playing against the rules of the apparatus and incurring different uses that subvert the way the photographic apparatus has been used to serve those extractivist practices throughout history. And I undoubtedly believe that the work of Roberto Huarcaya and others like Luz María Bedoya achieves precisely that.

Going a little further, I think it’s important to note that the place of the photographic apparatus in Western modernity is also linked to how we construct stories. Unfortunately, the photographer’s image has always been narrated in analogy with the hunter: the white man who goes to exotic lands with his rifle and captures prey. Belaúnde suggests this in her text: the camera is a weapon that steals images. This metaphor is historically relevant. But I also believe that the history from which photography is defined can be rewritten. I like to define it from the idea of the fabric: the photographic apparatus as an instrument that connects us with others. I don’t use the camera to steal from others. I use the camera as a bridge that allows me to weave a connection with others. But also to weave a connection between the past and the present, between here and there, between the familiar and the foreign. So, in rhetorical terms, what Belaúnde says makes sense if we buy into the idea of photography as a machine that steals. But if we redefine photography as a machine that allows us to weave connections with others, with “foreigners,” then history changes completely, doesn’t it?